Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention: Alayna N. Pernell

We are thrilled to share the 2021 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner, Alayna N. Pernell. Pernell recently received her MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

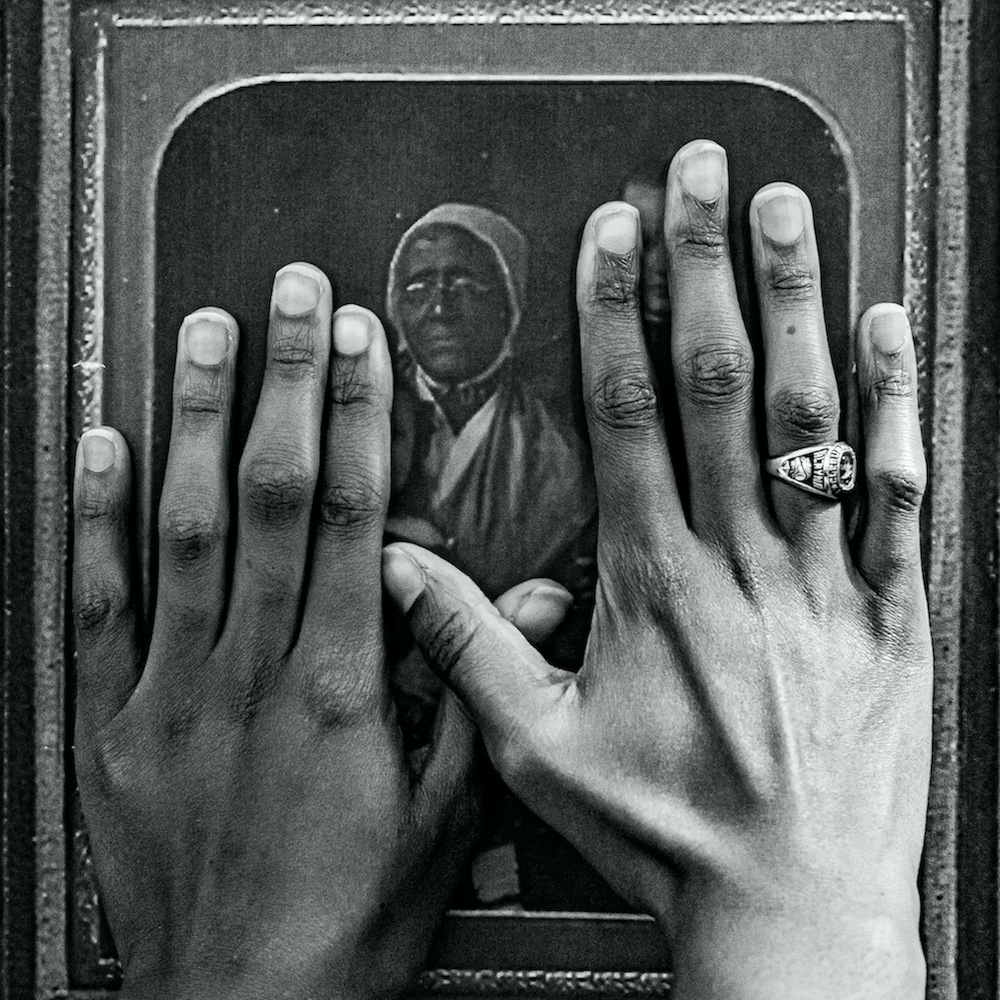

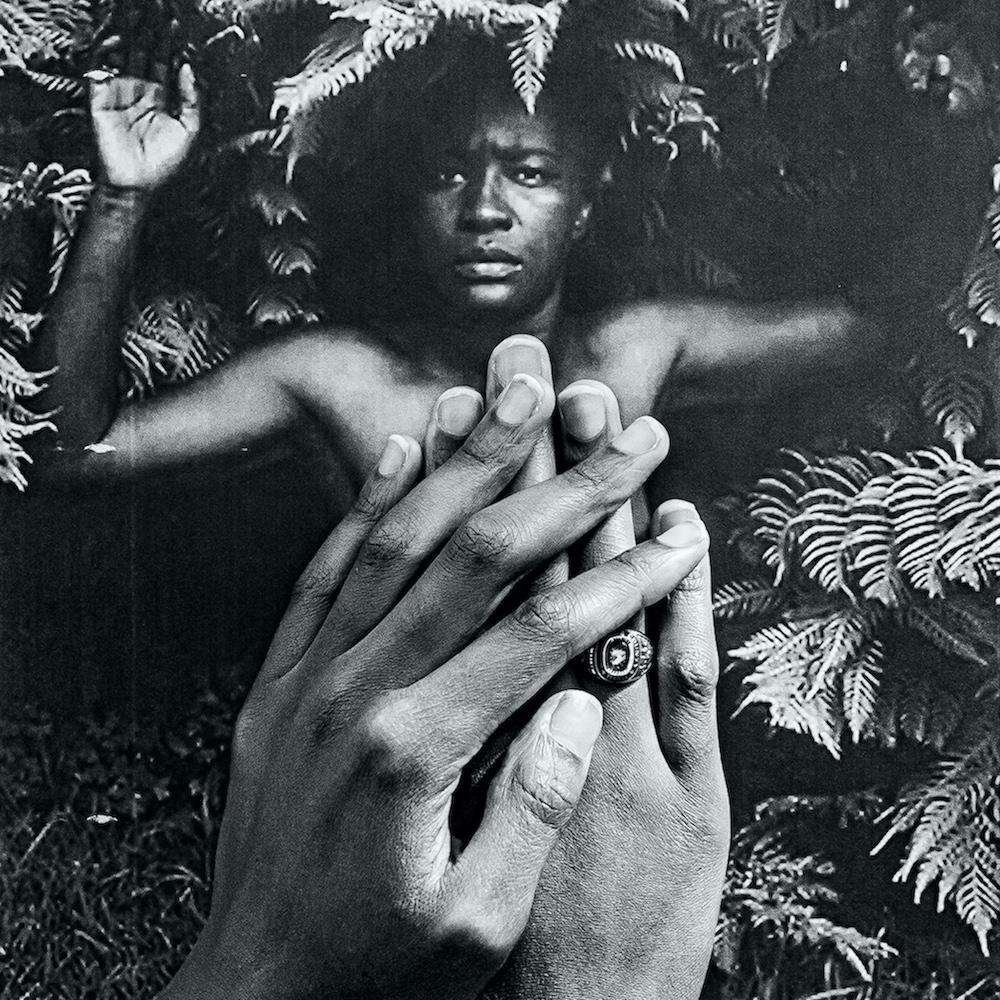

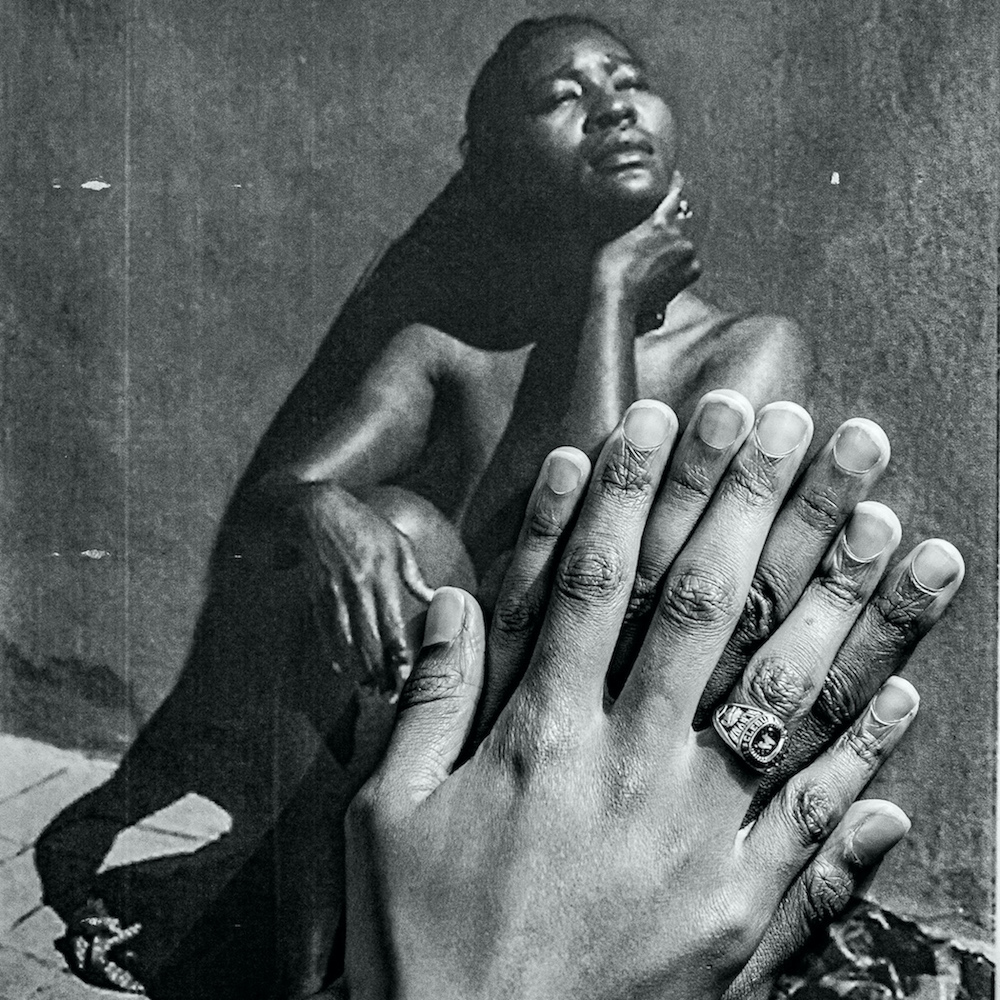

Aperture recently published a book called Photo No-Nos: Meditations on What Not to Photograph, and for me one of those things is usually hands, because I see so many photographs of them. Many times they are holding other pictures, to underscore the materiality of the image as object, or they are used to emphasize the act of creation by hand, as with someone practicing a craft. Alayna N. Pernell’s images in Our Mothers’ Gardens achieve a kind of interaction and engagement with both ideas and matter that escape the confines of any trope.

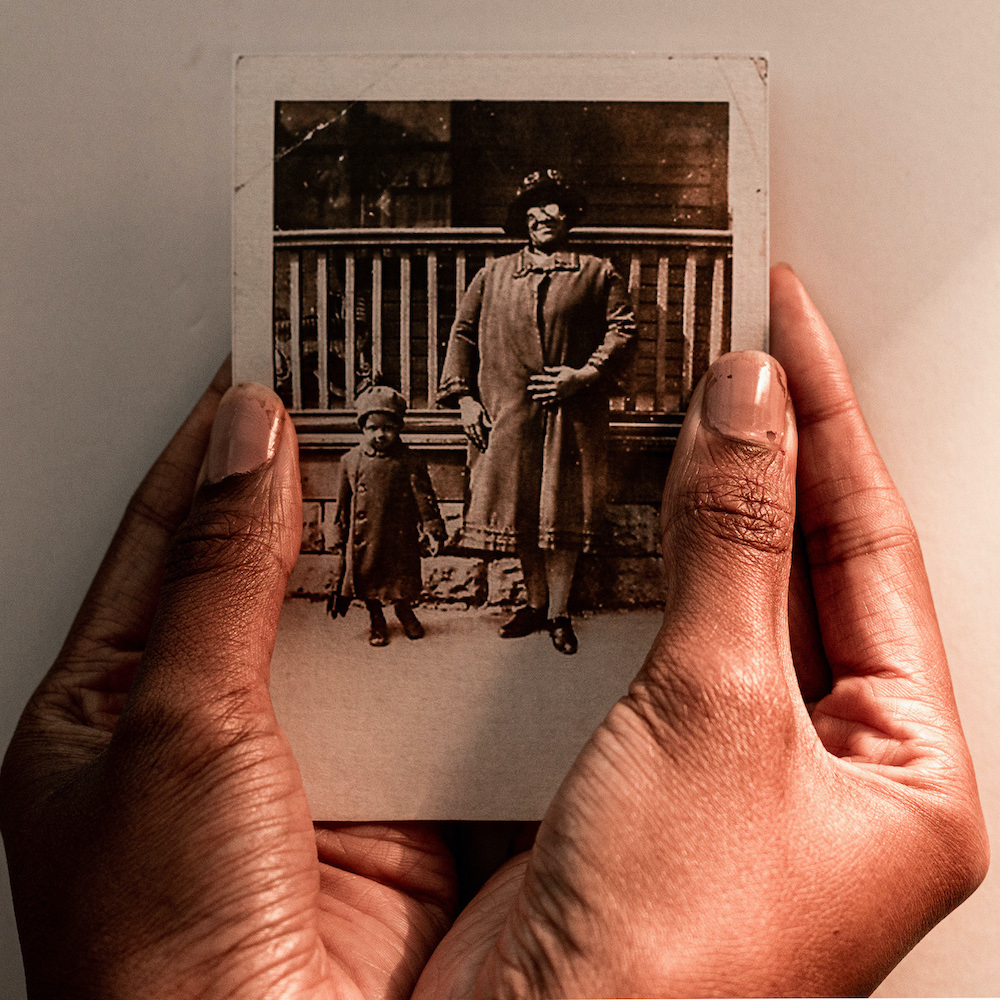

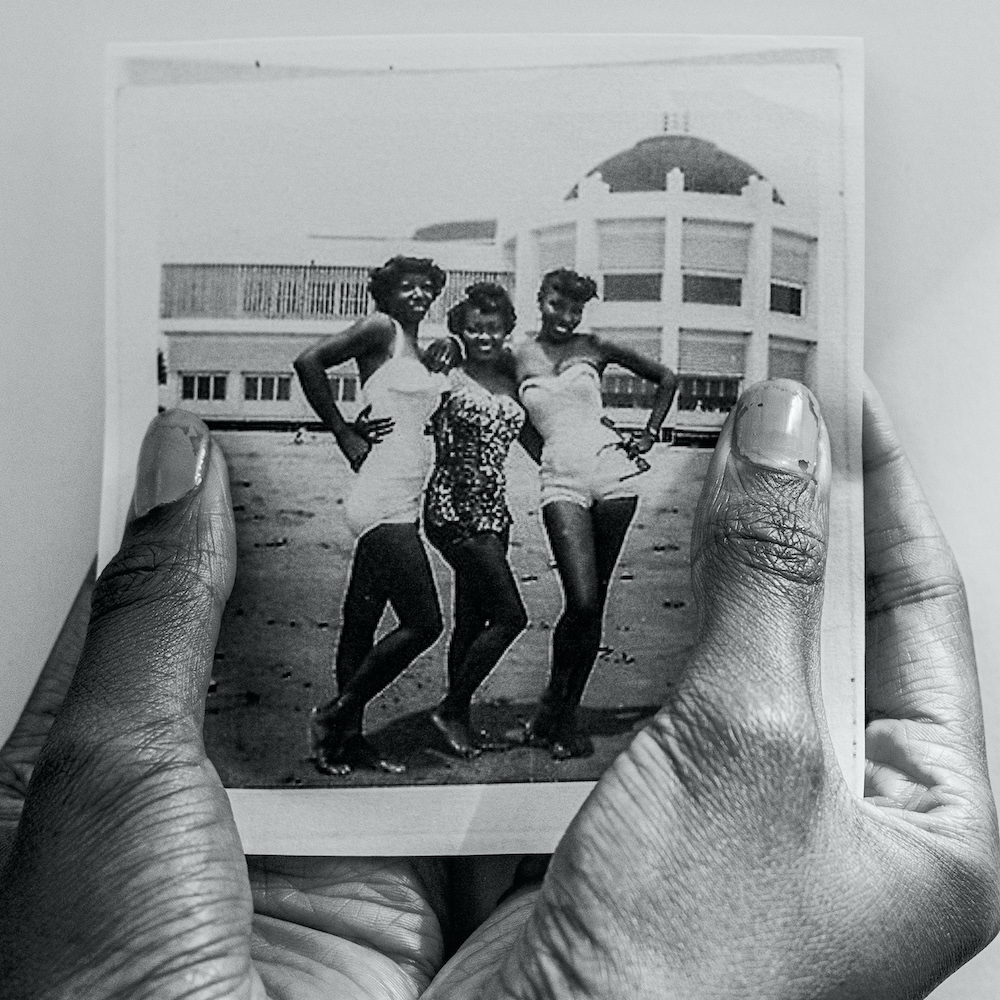

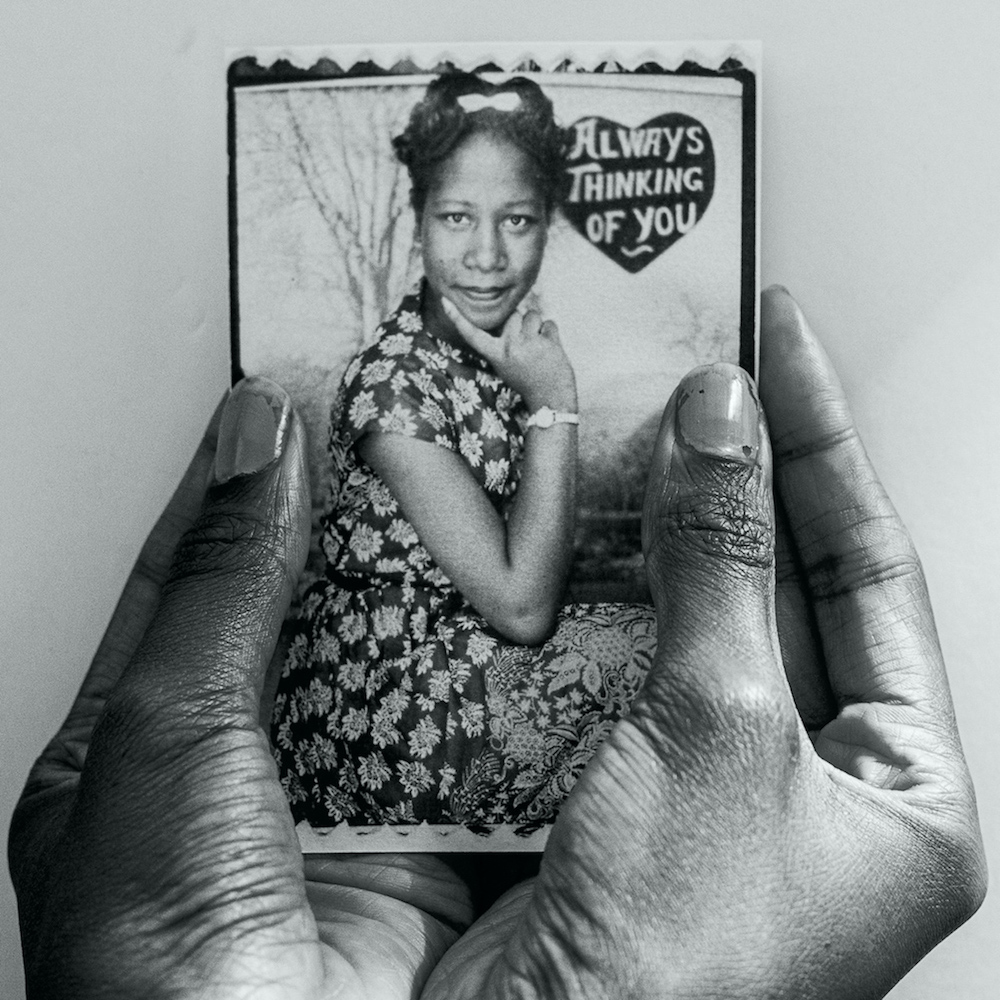

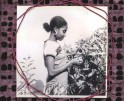

I was startled by the immediacy of her photographs, the power manifested in her laying of hands on the photographs of female ancestors. Pernell begins the series (as seen here) with a color self-portrait of her holding a family photograph, “Cradling My Ancestral Mother #2,” which skillfully, and poignantly, creates a context for understanding the rest of the series as you move through it image by image. There are so many layers here. The present and the past are engaged both by what’s pictured in the photographs but also through the use of color and black and white.

As a body, the photographs epitomize what is so important about the subjective, the personal, when thinking about the life of documents. These are fine art documentary images that prompt an immediate response, a recognition of what connects the maker to what’s contained within the frame. That different pairs of hands are pictured and that they move in relation to the photographs beneath them—change their posture—creates other kinds of understandings, of both feeling and comprehension. The hands frame, protect, embrace; they treat the original images, and the women in them, as treasure.

The photographs also provoke deep reflection about representation in, and the ownership of, images: Who is the subject? Who is the maker? Who owns the image and where does it live—how is it created, identified, presented, and preserved?

This project grew out of Pernell scanning her own family’s large collection of photographs but expanded to include snapshots from the Peter J. Cohen Collection of vernacular images at the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC). In looking for photographs of Black women in the archive, she was struck by how severed the relationship between the makers (most of them white men) and the sitters was, how erased the women’s names and narratives were (most of them are unidentified).

As she wrote in a letter to Peter Cohen, “While the images [in the collection] themselves are beautiful, I felt a great sense of sadness because they are not with their families nor are their names . . . visible. My discomfort comes from knowing that I can’t refer to the collection without saying your name instead of theirs. My discomfort also comes with knowing that profit was made and/or exchanged in obtaining these images.”

The women in the photographs, she writes elsewhere, “are someone’s mom, someone’s sister, daughter, wife, girlfriend or friend. Yet they are sitting in institutions like the AIC receiving no love at all. . . .” With Our Mothers’ Gardens, which is ongoing, Alayna N. Pernell performs a kind of restorative justice. With care and reverence, she is “saving Black women from the archive” and returning their images to their proper place, at home among family. They are “No Longer Peter Cohen’s Property.”

The Honorable Mentions winner receives $250 Cash Award, a feature on Lenscratch, a FUJIFILM X-E4 Body with XF27mmF2.8 R WR Lens Kit, Silver (MSRP $1,049.95 each), and a Lenscratch tote.

An enormous thank you to our jurors: Aline Smithson, Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Daniel George, Submissions Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Kellye Eisworth, Managing Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Alexa Dilworth, Publishing Director, Senior Editor, and Awards Director at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) at Duke University, Kris Graves, Director of Kris Graves Projects, Photographer and Publisher based in New York and London, Paula Tognarelli, Director of the Griffin Museum of Photography, Hamidah Glasgow, Director of the Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins, CO, Raymond Thompson, Jr., Artist and Educator, winner of the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize, Guanyu Xu, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2019 Lenscratch Student Prize and Shawn Bush, Artist, Publisher and Educator, winner of the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize.

Our Mothers’ Gardens

In 2020, I was feeling quite detached from creating work, and I hit a patch in my practice where my motivation to create temporarily subsided. This was a direct result of the social unrest and the pandemic. In June, I went back home to Alabama for a couple of months to be with family and rejuvenate my mind, body, and soul. I spent a lot of time between my Grandmother and my Mom’s homes, both of whom I am very close with. We went through photo albums together and loose images hanging around in tubs throughout my Grandmother’s home. It took weeks to go through hundreds of photos dating from the late 19th century to the present. This experience resulted in my attachment to vernacular images and what stories they revealed. Yet, this moment was also the catalyst to me questioning the stakes of when we are not able to speak for ourselves or lack full control over our own narratives.

Throughout history, there has been a unique curiosity to capture and study the Black body, especially those of Black women. Our bodies have continued to be seen as objects to capitalize off of and often times hardly anything beyond that. With these ideas in mind, my practice is currently revolving around two questions. What can visual art tell us about the depiction of Black women throughout history? How have those negative depictions of Black women resulted in our lack of mental and physical care?

I have spent months researching and uncovering suppressed images of Black women held in photographic collections at the Art Institute of Chicago. The images I have found and researched thus far depict the exploitation and violence towards Black women. In my practice, I have excavated, re-photographed, re-captioned, and re-contextualized the original works. By engaging with these images with the intervention of my hands and my body, I attempt to rescue and protect Black women’s bodies and their humanity, and also unearth their stories so that they can be seen and heard. With my ongoing body of work entitled Our Mothers’ Gardens, I beg for more than the visibility of Black women in institutional collections and hopeful reparations. I also desire for the issue around institutions holding and silencing collections of visible and (in)visible violent visual depictions of Black women to be further highlighted.

Alayna N. Pernell (b. 1996) was born and raised in Heflin, Alabama. In May 2019, she graduated from The University of Alabama where she received her Bachelor of Arts in Studio Art with a concentration in Photography and a minor in African American Studies. She received her MFA in Photography from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in May 2021. Pernell’s practice considers the gravity of the mental wellbeing of Black people concerning the physical and metaphorical spaces they inhabit. Her work has been exhibited in various cities across the United States. Pernell was also recently named the 2020-2021 recipient of the James Weinstein Memorial Award by the School of the Art Institute of Chicago Department of Photography; and the 2021 Snider Prize award recipient by the Museum of Contemporary Photography.

Tell us about your growing up and what brought you to photography?

I am from a very tiny town in the Deep South. I was born in Anniston, AL, but I was raised in Heflin, AL. At the schools that I went to growing up, Fine Arts were not something that was valued or given much attention. So, all the fine art that I learned came from my home. My Mom was very supportive when it came to me wanting to do anything artistically (painting, writing, music, etc.) and since I didn’t have that training at school, she made sure I was able to have that at home by providing me with the necessary materials (paint, paper, an easel, etc.). I didn’t get my first camera until I was 17 or 18 years old, and I loved it, but I was still primarily focused on painting and drawing until I was able to take a photography course.

I took my first black and white film class at The University of Alabama when I was a sophomore. From that moment forward, I knew that photography was the medium for me where I could successfully express how I’m feeling about not only myself and my life but also about the world around me. My love just grew from there and I’d say I advanced quickly.

In short, to be quite honest, what brought me to photography was my poor mental health. I started photography during one of the darkest places in my life which I reveal in some way in most of my work. Up until the time I picked up my camera, I expressed a lot of what I was going through in my paintings, but photography made me feel different. I can’t explain it, but for me it just worked. Photography saved my life (along with therapy and my supportive friends and family) during that time and has continued to save my life several times since then. It amazes me all the time how transformative photography is regardless of which side of the camera you’re on.

Congratulations on your Lenscratch Student Prize! What’s next for you? What are you thinking about and working on?

Thank you so much! I truly am so thrilled to have been selected as an Honorable Mention for the Lenscratch Student Prize. My cheeks have gotten quite the workout from all the smiling that I’ve been doing since finding out. Now, the next step for me, as an extension of Our Mothers’ Gardens (2020-) is restorative justice. I haven’t talked about it too much, but briefly, I can say that I was sent a selection of images from the Peter Cohen Collection from Peter Cohen himself. We’ve been in a decent amount of conversation these days, and he gave me permission to return the images to their families. So, I’m going to be putting all my energy into researching for that specific line of work as soon as I get over the bridge of other responsibilities that I must take care of at the moment. I do have an idea in my head as far as what I want to do next after I feel in my heart Our Mothers’ Gardens is complete, but that’s nothing I expect to really give all my mind and heart to until 2022.

We’re always considering what the next generation of photographers is thinking about in terms of their careers after graduation. Tell us what the photo world looks like from your perspective; what do you need in terms of support? How do you plan to make your mark? Have you discovered any new and innovative ways to present yourself as an artist or connect with others?

From my perspective as a freshly new graduate, on one hand, the photo world feels very competitive and cutthroat, and then, on the other hand, it feels so supportive, welcoming, and loving. I think it depends on the day and the time. Especially as a very new, emerging artist, it can feel intimidating at times, but the great part about this journey is that I have met other wonderful artists along the way, and I wouldn’t trade this journey for the world.

This is probably too blunt of an answer, but one thing that I do need at this moment is a job. I’m being as patient as I can with myself as I am in this zone of trying to find a job in this field that I love. I love making images and I love having conversations about photography, both historical and contemporary; and I would love nothing more than to do that for the rest of my life. So, for right now, that is the true need for me at this moment because I am also a human being and a working adult, and I sadly can’t live for free in this country. This is also a huge reason why I’m so thankful when I receive any financial support, like from Lenscratch, because it means so much to me to be supported doing what I love and what matters so much to me.

Though for now, I plan to continue doing my best to make my mark by continuing to speak my truth as a Black woman and by continuing to really put myself out there. My Mom always tells me that it only takes one person to notice, and I carry that with me throughout everything I create and everything I submit and show. I feel like if I keep doing this and then some, I’m going to get far places and really make my mark in this community, and hopefully while I’m still alive to see it all happen. I firmly believe that it will happen and I’m keeping that confidence within myself.

Social media is a lovely tool when it comes to presenting yourself as an artist and connecting with others. I personally have made so many new photo friends just through Instagram alone. Just as a bare minimum, it really pays to be genuinely kind to people, not to suck up to people for any ulterior motives, but to really be kind to people and be genuinely supportive of other artists because we’re all just trying to figure things out.

Are there any instructors or mentors you would like to acknowledge?

Oh, I have quite a few. I really want to start with the very first instructor who I felt genuinely believed in me—Allison Grant, who is the Assistant Professor of Photography at The University of Alabama, my alma mater. She supported me in undergrad and supported my post-undergrad plans to go to graduate school. I don’t think that there will be a time where I won’t acknowledge her because I don’t believe that I would be where I am today if it wasn’t for her believing in me and believing that I could even go to grad school or make wonderful work one day– and that day is here.

I give so many thanks to quite a few of my instructors and mentors at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago that have really guided me throughout making this work. In some way or another, whether it was challenging questions or many resources it really keeps pushing me to think further and deeper about everything that I create. I am forever thankful for LaToya Ruby Frazier, who I worked closely with during my last year of graduate school. I learned so much and grew so much from working with LaToya and I’m so honored to have her as a mentor. I would like to thank Nia Easley, who was one of the first instructors that I met during my first semester of grad school, and it was through taking her course (History as Material) in my last semester of grad school that aided in my ideas for Our Mothers’ Gardens to fully blossom. I’m thankful for Dawit Petros and the insightful knowledge that he would provide so generously. I’d also like to give my thanks to Jan Tichy who has been a very supportive instructor and has always been very helpful and kind when I needed any guidance or support in my work or as a student.

Last, but not least, I’d like to acknowledge my Mom for being my forever rock and for supporting me throughout everything I do, especially as an artist—because of her, I am.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention: Chantal LesleyJuly 22nd, 2021

-

Lenscratch Student Prize Award Honorable Mention: Lois BielefeldJuly 21st, 2021

-

Lenscratch Student Award Honorable Mention: Vanessa LeroyJuly 20th, 2021

-

Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention: Alayna N. PernellJuly 19th, 2021

-

Lenscratch Student Prize Third Place Winner: André Ramos-WoodardJuly 16th, 2021