Earth Week: Michael O. Snyder: The Coming Coast

I met Michael O. Snyder, photographer, filmmaker, and environmental scientist, at the 2021 Review Santa Fe Portfolio Review. I was so moved by his projects and his ability to tell stories through traditional documentary and conceptual fine art approaches that I invited him to be the editor this week in recognition of Earth Day which falls on April 22nd, 2022. I am so grateful to Snyder for all his efforts this week, in the selection of artists and in his editing, as well as the focus of his own work important work, as we consider the planet in crisis. He states about his selections:

These bodies of work are linked by this thematic lens: making the often-invisible nature of the global climate and the ecological crisis more visible using conceptual, lens-based art techniques. Each body of work speaks to a different aspect of the climate and ecological crisis: sea level rise; coral bleaching; habitat loss and environmental destruction; deforestation; melting glaciers; plastic pollution.

Today we begin with his own project, The Coming Coast, which is a disturbing look at the issue of sea level rise. For almost a decade Snyder has been documenting sea level rise around the US, studying both the impact and the solutions that communities are considering. In 2020, he was awarded a climate journalism fellowship through the Bertha Foundation to continue this work and when the pandemic hit, he had to contemplate new ways in which to tell the story.

He shared his process in a recent article in Buzzfeed:

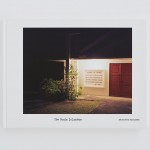

So the question that underlies The Coming Coast was how to make the often invisible nature of sea level rise more visible. I decided to work in the Chesapeake Bay because it is ground zero for sea level rise. The first thing I did was to map what sea level rise will look like. I worked with Climate Central’s mapping tools and used their data to generate maps showing what sea level rise could be by the year 2100 if we don’t get much more serious about mitigating climate change.

Step two was to travel around the Chesapeake Bay and follow this new coastline. I used thick blue painter’s tape and placed it throughout these communities to show where the coastline is going to be sometime between now and 2100. It was actually quite difficult to put the tape right where the line will be — I was just in too many people’s properties — so instead I decided to create a coastline that will be sometime between now and the year 2100. Obviously it’s imperfect, but it gives you a general sense. A lot of these places where I worked are quite dry right now. And they are everyday places that you might go to, like a public park or a backyard or a parking lot.

I used a drone to take photographs of four communities on the Bay Hundred peninsula of Maryland. These were: St Michael’s, Oxford, Bellevue, and Tilghman. They all have different socioeconomic and racial compositions and histories. Using those maps that I had generated with the climate central data, I painted into the drone photos where that sea level rise could be by the year 2100.

Finally, I chose 30 individuals from around the Chesapeake Bay. I wanted to get as diverse of a group as possible, because climate change is one of these issues that is going to impact everybody. I took a portrait of each person and asked them to stand in a spot that mattered to them, and in that spot I asked them to hold a depth stick that would show what 6 feet of sea level rise would look like for that location.

These are very different people. They have some things in common, they may or may not like each other, but they are on the same team. And of course the big question is: Are these communities going to try to migrate away from the coast? Or are they going to try to build up? It is not just a question of the impacts, it is also a question of privilege: What ability does that community have to survive? And it is very unevenly distributed.

Michael O. Snyder is a photographer and filmmaker who uses his combined knowledge of visual storytelling and conservation to create narratives that drive social impact. Through his production company, Interdependent Pictures, he has directed films in the Arctic, the Amazon, the Himalaya, and East Africa. His photojournalism work has been featured by outlets such as National Geographic, The Guardian, and The Washington Post. He is a Portrait of Humanity Award Winner, a Society of Environmental Journalists Member, a Pulitzer Center Grantee, and a recent delegate to the United National Climate Conference. He holds an MSc in Environmental Sustainability from the University of Edinburgh, Scotland and a BSc from Dickinson College, Pennsylvania. He lives in the shadow of the Blue Ridge Mountains of Central Virginia.

Follow Michael O. Snyder on Instagram: @michaelosnyder

©Michael O. Snyder, A line of tape shows where the new coastline will be under worst-case-scenario projections. from The Coming Coast

The Coming Coast

The Chesapeake Bay of Maryland and Virginia is one of the world’s truly exceptional geographies. Despite being only 200 miles from end to end, the Bay packs in over 11,000 miles of crinkled, marshy coastline. Stretched out, this is line would be long enough to wrap nearly half way around the planet. The geophysical structure of the Bay allows it to act like a sieve – an aquatic lung – that filters water for millions of people and provides critical habitat for thousands of endemic and migratory species. But the waters of the Chesapeake Bay are rising due to climate change and the lung is rapidly filling up. Already, three vertical feet of shoreline have disappeared since the time when Captain John Smith first sailed into the bay in the 1600’s. Climate models suggest that an additional 3 – 8 vertical feet may yet slip below the waves before the end of this century. While this might not sound like much, a rise of this magnitude would spill out laterally across a vast, low-lying coastal plane, swamping tens of thousands of acres of marshland and destroying 3 million homes by the year 2100. Some islands have already disappeared. The eulogy is being written for others. Whether we recognize it or not, a new coastline is coming. The Coming Coast documents a journey along the 11,000-mile coastline of the Chesapeake Bay as it may yet be in the year 2100. Along the way, I use thick blue tape to mark the path of the coming coast as it snakes through neighborhoods, main streets, and storefronts that are sometimes miles away from the water. Also, I meet and photograph a diverse group of people who are actively working to hold back and adapt to the rising tides. The purpose of these portraits is to understand how individuals from desperate backgrounds, lifeways, and perspectives can, quite literally, find common ground and work together to protect a shared resource. The project understands that geographies, much like pressing social issues, can either divide or unite us. The Coming Coast is an exploration of dynamic spaces and the messy work of finding unity in an age of division and unprecedented change.

This is Horn Point Laboratory in Cambridge, Maryland. And this is the first place that I realized that I wanted to dive into bay conservation and restoration. I’m a faculty member here now. And in the fall of this year, I’ll be a full-time grad student.

In general, African American stories of working on the Chesapeake Bay have been lost and actively forgotten over the years. I was no exception to that case. It wasn’t until my mom started diving into our family genealogy, that I found out that I’ve had waterman in my family for a long time, probably since the 1800s. And so, I think that makes it even more special that I want to do it. I’ve recently started a non-profit organization called Minorities in Aquaculture. And the goal is to educate people, in general, about aquaculture and sustainability, but specifically, women who are a minority in a male-dominated field, and even more specifically, women of color, who are a double minority. I wanted to start an organization to help close that gap and take out the obstacles that minorities go through when it comes to getting internships, and mentorships, and access to financing.

But climate change and sea level rise are a big threat to what we are doing. Oysters, in particular, are very temperamental creatures. They face a lot of threats, but ocean acidification, which is caused by climate change, is a big one. But, you know, the great thing about farm-raised oysters is that they’re designed and cultivated to handle those kinds of fluctuations in salinity, temperature, and PH. So sustainable aquaculture is going to have a big role to play in the future as things keep changing more quickly. Right now, we’re putting millions and millions of oysters out there in multiple different tributaries. These can go from farm to table in three years, and in one year they can filter 19 trillion gallons of water in the bay. Sea level rise is the other big threat because it is going to wipe out wetlands and so many historical spaces, like generational homes and occupational history, in a matter of 15 to 20 years. Recently, it’s been great to see diversity and inclusion as a part of the conversation about conservation. But we need to set tangible goals, rather than just aspirations. The fisheries in the Chesapeake Bay are a national treasure and the Black community has always been a part of that. For me, sustainable aquaculture is going to be the way to keep it going. – Imani Black

This is a ghost forest. The salt water is coming in and killing these trees. And there are thousands of acres of this, like sticks standing out in the marsh. There was once a thriving timber business here, but it’s all gone now, because when you harvest the trees, the land underneath just gets wetter, and it will never support trees again. It’s like we are looking at the very last harvest here. We’re living on borrowed time.

As best as I can tell from people I’ve talked to, there’s always been sea level rise. But I think it has got to the point where it is happening faster and really became noticeable. It’s really accelerated in the last 20 years. There’s a place where I used to fish when I was a kid and, well, where I stand today to fish is a half mile further inland. Sometimes I can hardly believe it. I’ve been a farmer now for 34 years. I know one guy that’s lost near 100 acres to salt water. In fact, there’s people doing studies just now trying to figure out what crops you can grow best in salty fields.

If you don’t live here, I think it’s out of sight, out of mind. But if you’re here, it is pretty mind-blowing to see what is happening. Already 30% of this county is in a flood zone. And how are you going to keep the roads above water? Because, as sea level rises, you can’t just keep putting blacktop on blacktop and marsh, because it just keeps sinking. So people leave, and the tax base evaporates, and houses get abandoned. And new people aren’t buying places down here. I can’t see a young couple making a living down here. I’m not smart enough to tell you how to change this. And I’m not sure anybody can. I do know that we have some hard decisions to make. But if there’s small solutions to this problem that everybody can do, then why not? We have to try.

A lot of the old-timers were deniers, and you know, I can understand that. And even today, a lot of people can’t stand to bring it up at all. Because, you have to understand, this is heartbreaking. Can you imagine losing your place? Folks here wouldn’t rather live anywhere else on Earth, you know. They’re proud of that. So it is really hard for people to admit it or talk about it. But if you can’t see it now, you never will.

We’ve lost islands in the bay in the past, and people have had to move off and make a living someplace else. The people here are strong. They will do it again. But it just won’t be here. And that’s heartbreaking, if I’m honest. – Donald Webster

©Michael O. Snyder, A line of tape shows where the new coastline will be under worst-case-scenario projections, from The Coming Coast

The very first time I ever saw a real live sewage overflow, it changed my life. Which sounds crazy! That’s not really the kind of life-changing experience that you want to hear about. But it really did, because I realized for the first time how important all of this is and how nobody knows anything about it. Like, nobody teaches you about urban infrastructure in school, but we are totally dependent on it. And the situation is really bad.

We’re supposed to have this dedicated sewage system that goes to the treatment plants, and then a dedicated stormwater system that just dumps into our local waterways. But the pipes, they’re old and leaky and overflowing, so we end up with an accidental combined system. So we have sewage mixing everywhere. A lot of people have this misconception that water in stormwater pipes gets treated or cleaned or whatever. And it’s just not true. It’s just there to convey water. That’s all it does. This is a long-standing problem that is being made much worse by climate change. Because now we get these really intense, hyperlocalized rain bursts, that cause flash flooding into these overburdened pipes. Our pipes are just too small capacity to handle this kind of event, so they mix into the sewage pipes, back up, and cause sewage to explode out into the streets. This isn’t theoretical. It’s happening. We see it, and we can measure it.

Then, at the same time, we have sea level rise, which is rising up into the outflow of the pipes, filling them with seawater, and causing a serious capacity reduction. So when all of that storm water starts gushing through the pipes, instead of just emptying out into the waterways like it was designed to do, it just backs up, and we’ve got sewage flowing through our streets. We used to have a couple hundred of these events every year, but just last year alone we had over 7,000 sewage backups in the city of Baltimore City. Yeah, it’s nasty. And it’s not just the explosive events. There’s a constant low-level trickle of sewage entering our waterways all the time. It’s an enormous, disgusting problem, and it’s only getting worse. And the sad thing is, it’s not just people who are being impacted, it’s the environment too. This water right here is teeming with life. The sewage is really high in nutrients, so it causes algal blooms, which chokes off all of the oxygen in the water and causes major die-offs.

I’m the Baltimore Harbor waterkeeper and I work with Blue Water Baltimore. And we’ve got to hold the city accountable to keep it on track to fix this problem. But the situation is only going to get more challenging with climate change, and it’s not going away any time soon. – Alice Volpitta

©Michael O. Snyder, A line of tape shows where the new coastline will be under worst-case-scenario projections, from The Coming Coast

©Michael O. Snyder, A line of tape shows where the new coastline will be under worst-case-scenario projections, from The Coming Coast

This is Old Trinity Church. We don’t know exactly when it was built. Our sign out here says 1692, but it’s older than that. Perhaps the 1670s. It was one of the earliest expressions of our faith on the Eastern Shore. It’s a place where people have connected with nature and with their creator for more than 300 years.

And the truth is, erosion has been happening here for centuries. Places like James Island and Holland Island are already gone. But now, in addition to being a place that is sinking, we have anthropocentric climate change as well. So it’s a double whammy.

But when we talk about climate change, the first thing is that, you’ve got to meet people where they’re at. Everyone knows that, for example, erosion is a problem. Even if you are a climate denier, you know that things are changing. So we can start with that. For me, having this conversation is about being present and being an example, rather than preaching. I’m a preacher. I know that preaching to someone who doesn’t want to be preached to has the opposite result than I intended it to have. So being present means being welcoming.

Twenty years ago, we realized that the shoreline was under severe erosion. It was bad. we built a living shoreline here, around the property. It’s basically re-creating a little marsh, closer to what the original shoreline would have been like. It’s designed to have water spill over the breaks and into all of these different kinds of grasses here. We were one of the earliest adopters of the living shoreline idea, at least in this area.

But ultimately, you know, there is a natural birth and a natural death for all things. Even for this church. It was founded back in the 1600s, and someday it will be gone. A century? A thousand years? I don’t know. God gives everything a beginning and an end. Things have their purpose for a time. And while this is here, and it exists for this purpose, we need to make sure that we take care of it. And so, we try to be responsible and to preserve things. We may be fighting a losing battle. And if that’s the case, then someday we have to be able to say goodbye. Because, I don’t see a way to move the church or the graves. The church is as much connected to this land as the land is connected to the church. So this place is transitory. Life is transitory. Not even the pyramids will last forever. But in the time that we do have, we have to enjoy it and be responsible for it. We are just stewards. – Rev. Dan Dunlap,

I grew up in Baltimore. And my dad was a hunter and fisherman. And that’s how I got my initial introduction to life on the Chesapeake Bay, that’s when I really got the salt water running in my veins. So I’ve always called myself a country boy from East Baltimore.

I noticed that in books on the Chesapeake Bay, very seldom you will see people of color. If you did see them, the caption was just “crab picker” and no other information. We launched the Blacks of the Chesapeake as a project, to document the contributions that African Americans have made to the maritime and seafood processing industries. And not only were African Americans integral in the seafood processing industries, but they were also boatbuilders, and business owners of seafood restaurants, and processing plants, and African American boating and yacht clubs. When we started this project, people were saying, Well, Blacks weren’t explorers, Blacks can’t swim, Blacks can’t sail, Blacks can’t fly. And of course, they could, and they did. For me, it’s really been about discovering things hidden in plain sight. It’s one thing to not have our African American history told. It’s another thing to be airbrushed out. And that’s what happened. So, we are trying to recover that and, at the same time, trying to lift up a downtrodden people. And, as an educator, I know how important it is for kids to see strong people that look like them. That can make a big difference in a kid’s life.

African American communities on the bay, they often wound up living in the swamps, because that was low-bottom land. Low value, high mosquitos. You couldn’t grow tobacco, so it wasn’t useful. But, of course, these are the places that have been impacted by sea level rise. One of the things that we saw in Louisiana, during Hurricane Katrina, was the problem of air properties in these African American shoreline communities. The whole concept of an air property is there’s not a clear title to the land. What happened is that a piece of land had been handed down from one generation to another, but it was always collectively owned. In African American and Indigenous traditions, nobody owns the dirt. We’re just stewards. See? And so that value gets lost. And so that is something that I’ve thought about here in the bay with African American communities as the seas start to rise. How will we make sure that folks living on air properties are protected?

And so, with Blacks of the Chesapeake, we are now thinking about not only stories that we capture, but environmental justice, climate change, racial equity, ecology. I mean, it’s all connected. A lot of people talk about formal education as the key to creating this change. It’s important, but it’s not the total key. You’ve got to put people in a position where they can better understand either other, rather than leave the table further apart. So I try to distill it down to the basics. Do you want clean water? Do you want a safe place to raise a kid? Because, once you start talking about parts per million, they are all going to disengage. So the change comes from thousands of small conversations that brings things down to lived experiences. It’s sharing our stories and finding out how we connect. That is what counts. – Vincent Leggett

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shinichiro Nagasawa: The Bonin IslandersApril 2nd, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Lorraine Turci: The Resilience of the CrowMarch 16th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Rayito Flores Pelcastre: Chirping of CricketsMarch 14th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Louise Amelie: What Does Migration Mean for those who Stay BehindMarch 12th, 2024

-

Brandon Tauszik: Fifteen VaultsMarch 3rd, 2024