The 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize First Place Winner: Drew Leventhal

Today, we are thrilled to announce and celebrate the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize First Place Winner, Drew Leventhal. Drew received his MFA at the Rhode Island School of Design. Leventhal’s project, Mason & Dixon, is a potent investigation of land and place that holds conflicted and traumatic histories. His work traverses the friction embedded in the past and his “ethnographic observations of a nation unsure of itself.”

Leventhal will receive: a $1500 Cash Award and a feature on Lenscratch, a $250 cash prize from The Griffin Museum of Photography, a $500 Gift Certificate from Freestyle Photo Supplies, a $500 Gift Certificate towards a Los Angeles Center of Photography Workshop, a $1000 Gift Certificate towards a Santa Fe Photo Workshop, a mini exhibition on the Curated Fridge, a collection of books from Yoffy Press, a collection of books from Kris Graves Projects, a collection of books from St.Lucy Books, a year long mentorship with Aline Smithson, and a Lenscratch T-Shirt and tote. So much appreciation to our wonderful sponsors.

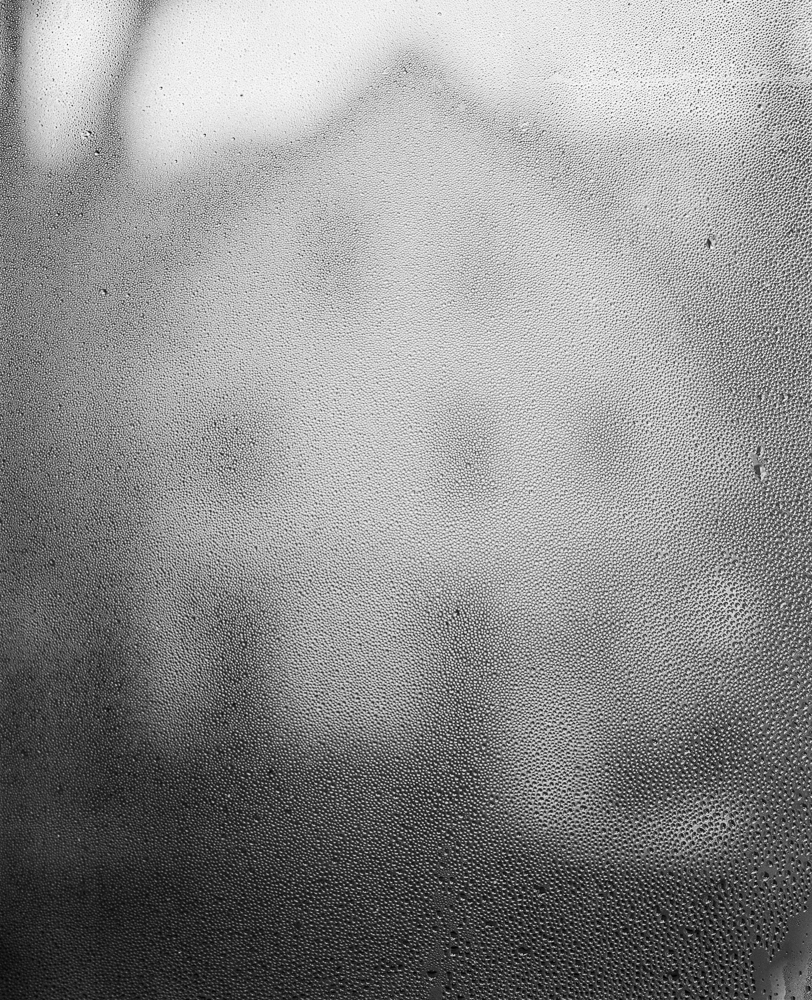

Leventhal’s work eminds me in an odd way of Nancy Rexroth’s Iowa (the Home picture through the condensation on the window). They are pictures of place as a state of mind, and possibily as a condition. What do ideas of North and South mean in 2022? The past is always alive in the present; as Faulkner famously puts it, the past is never dead, it’s not even past. And while the Mason-Dixon Line delineated the separation between free and slaveholding states (Pennsylvania and Maryland), what does it mean for us now? We are living in a time when we are acutely aware of difference, of delineations, borders, boundaries–of places where the right to dominion over one’s own body is being lost. These photographs are about tracing the (power) lines, following marks on the land. What do we experience as citizens when we cross a border where there are no signs, no checkpoints, where both sides of the division look exactly the same? How do we know we have arrived somewhere else?

Leventhal writes of the “invisible cartographies that frame our identities.” The photographs are about mythologies of self and identity that mirror the culture, it’s history and politics. What does it mean to re-enact the past in the present, why do people want to do it–as a means of connecting more closely to the past or as a way to re-inscribe it with something new?

The image that Leventhal shares of the monument of a man on a horse (a general? a soldier? for what side?), taken through his car window speaks to the frame through which we see ourselves in a past-fueled landscape. We can see Leventhal, making the photograph, in the rearview mirror. He’s traveling, searching for what’s visible, for what can be found outside of himself, but he’s inside a vehicle, and behind his windshield and his phone. This is ultimately a trip of self-reflection. If a place is defined by and memorialized for its conflicts, is unity ever possible among the people who live there?

Two deer cross a road, a bridge crosses a dry creek, a man and his son look behind them, at what’s on the other side of the barrier they are sitting on. Reenactors assemble around their camps. The faces are both young and old. Then is now; there is here.There is still some wildness, a lush patch of ferns, an algae-covered pond. Stands of forest. Are these photographs evocative of a way of being as yet unsubdued, uncontrolled, something having to do with potential, or do they indicate something else? All of these places are accessible by road and therefore are already marked.

The stories that divide us are the same ones that bind us, as Leventhal notes. Perhaps the only way to find connection is to examine the seams, to recognize them and make them visible.

An enormous thank you to our jurors: Aline Smithson, Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Daniel George, Submissions Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Linda Alterwitz, Art + Science Editor of Lenscratch and Artist, Kellye Eisworth, Managing Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Alexa Dilworth, publishing director, senior editor, and awards director at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) at Duke University, Kris Graves, Director of Kris Graves Projects, photographer and publisher based in New York and London, Elizabeth Cheng Krist, Former Senior Photo Editor with National Geographic magazine and founding member of the Visual Thinking Collective, Hamidah Glasgow, Director of the Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins, CO, Allie Tsubota, Artist and winner of the 2021 Lenscratch Student Prize, Raymond Thompson, Jr., Artist and Educator, winner of the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize, Guanyu Xu, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2019 Lenscratch Student Prize and Shawn Bush, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize.

Drew Leventhal (he/him) is a photographer working with themes of colonial history, family, and the ways memory shapes identity. Raised by two anthropologists in Philadelphia, PA, Drew is drawn to the ways photography can be used to reveal narratives about people and cultures in their landscape. His work blends ethnographic fieldwork with an eye for wonder and mystery.

Drew attended the International Center of Photography and recently completed his MFA in photography at the Rhode Island School of Design. He is currently based in Providence, Rhode Island.

Follow David Leventhal on Instagram:@drew_leventhal

Mason & Dixon

My project, Mason & Dixon, traces the footsteps of the original surveyors of the Mason-Dixon Line and their search for purpose in the borderlands between Pennsylvania and Maryland. For the past 250 years, the Line has inscribed a violent and painful scar on the land, filled with memories and (re)written histories. Holding the legacies of slavery and colonial expansion deep in its soil, the region is now a visceral example of the ongoing divisions and conflicts around the past, the present, and the future of the United States. The friction is in the air, in the monuments, in the clearcuts. I often ask myself how the land can support this unbearable weight.

I photograph along the Mason-Dixon Line because I am looking for connections between the divides: connections to the people I meet, to the land I grew up on, and to the history I am a part of. The irony is that the relationships that bind us are also the stories that divide us; that make a miasma that is perilous to traverse. But when I cross the dividing Line nothing changes, even though the signs say it is there. When I cross the Line it becomes mythology and I am left searching for a constellation on the ground I cannot find.

The Mason-Dixon Line is a line we all draw as we try to manifest an American identity. Utilizing large format black and white photography, the images in this project are my ethnographic observations of a nation unsure of itself. They are my accounts of where we have been, where we are, and where we are going.

Congratulations on being the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Winner! Let’s start at the beginning and have you describe the landscape of your growing up.

Thank you so much Aline! It’s really an honor to be talking with you about the work, I’m excited to get into it. Just a few weeks ago I never would have thought I would be in this position. Thanks so much to the jurors for all the hard work they put into looking at so many amazing projects.

I think it’s important to start by saying that I grew up the only child of an upper-middle class family. The ability to be immersed in art and to have the freedom to pursue the path of a photographer is one that comes from extreme privilege and generosity. I had a lot of help getting to this point and thats not something that’s openly talked about enough in the photo world.

When I was young, my family moved around a fair bit. First California, then to New Mexico, and on to Philadelphia, where I consider myself to be “from.” Both of my parents are anthropologists, so I would also accompany them on their fieldwork. With my dad that meant going to Belize and Mexico and learning about archaeology and heritage, how histories come to belong to people. With my mom it meant going to Comic-Con and studying these rabid fan cultures that create languages and symbols out of thin air. So I guess you could say it was an eventful childhood! Thinking about it later on, I think that continuous movement contributed to the sense of wanderlust I feel now when I go take pictures.

You mention that both your parents are anthropologists. Does their way of seeing the world impact your practice?

I love talking about this part because anthropology has been hugely influential to my practice and my worldview! I see anthropology and photography as two sides of the same coin. They’re both searching for the hidden poetics of the world, what the anthropologist Clifford Geertz called “Thick Description.” I especially love that term because it hints at things that necessitates a relationship to understand and record. Some symbols or gestures are so complex, so layered, that they necessarily escape individual understanding. Only by combining viewpoints, something that happens in anthropology as well as in the photographic dialogue, can a truly thick understanding come about.

Of course, regardless of how many dialogues we have these slippages into the deep tell us everything and nothing about the world we live in. It’s an irreconcilable dichotomy that I think is at the heart of great photography and great anthropology.

Anthropology and photography are also the two most self-conscious disciplines. Throughout their histories they have admitted (not without great turmoil!) that the violent traditions they were founded on were wrong and have sought out new ways to be better and new voices that must be heard. It is a continual process that keeps my mind open to new paradigms and perspectives.

What brought you to photography?

It was actually something that I fell into by accident! There was nothing about me as a kid that screamed artist. In high school I was a terrible painter and drawer, I thought maybe I would be a chemist or an engineer of some kind. For awhile there growing up, even into college, I didn’t know what I wanted to do, I didn’t have a lot of ambitions. But one day my mom gave me a really old DSLR and I started carrying it around with me. I took pictures of my friends, the fall leaves, whatever drew my eye. There were even some kind of grim self portraits in there that will never see the light of day! It was fun and I liked the relationship I had with the camera, it gave me an excuse to be in places I otherwise wouldn’t go. But you know how some people say they had that moment where photography just “clicked” for them? I never had that eureka moment, it was a much slower burn. Photography was just the thing I kept going back to year after year.

In college I started combining photography with the other things I was learning about the world. I ended up following in my parent’s footsteps and getting a degree in anthropology. For my senior project I was working through Ariella Azoulay’s Civil Contract of Photography and questioning how we could rewrite the interactions between the photographer, the subject, and the observer. I did fieldwork in a small town in Mexico, where I engaged in collaborative photography and interviews as a way of examining how people viewed their own cultural heritage. It was only partially successful project in its outcomes but suddenly photography was this magical tool to engage with the world and comment on it! That was a big discovery that I am still working through today.

All of that is to say that my journey with photography has come in stuttering steps. I think that is actually more common than we might think, not everyone’s relationship with photography is a spirit bond between the artist and the camera. I never knew, until very recently, that this is what I was meant to do!

What kind of work were you creating when you entered graduate school?

It’s funny looking back at that work because in many ways it feels very similar to what I was making in college and also what am making now, almost like a liminal body of pictures. In 2019 I started making work about a family friend in Belize who had recently died. His name was Yosh and he was this complicated figure, a white British colonial officer who found his home with the indigenous Maya, eventually marrying a Maya woman and starting a family.

I was just beginning to explore documentary photography and I was using these really vibrant colors, lots of landscapes and portraits, trying to make some sense of all of the symbols I was seeing in Belize. I was definitely inspired by Alessandra Sanguinetti’s work. The Belize project is not finished and I think its something that I will be working on for a long time, but it taught me a lot about how I could begin putting pictures together to imply a narrative.

What compelled you to traverse and photograph the Mason & Dixon line?

Actually on that same trip to Belize I started reading Thomas Pynchon’s novel Mason & Dixon, which a friend had lent me. I was hooked immediately on Pynchon’s blend of fiction and history, his use of anachronism, and the way this line on the ground could do so much damage to so many people. I didn’t know what was going on half of the time I was reading this book but I knew I loved it like nothing else I had seen before. So that sparked my interest in the Mason-Dixon Line and I originally wanted to make pictures as a sort of visual novel accompanying Pynchon’s text. If you squint maybe there is still a bit of that desire in the work!

What kind of research did you do for this project?

Well, once I moved away from Pynchon’s novel and started looking into the actual history of the Mason-Dixon Line, I found so many stories and angles to explore. The biggest issue I have had is actually deciding which parts of this project have to fall by the wayside because there is just so much going on!

I started by looking into the original surveying of the Line in the 1760s. The two surveyors, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, kept a journal filled with star charts and progress reports. It is a fascinating account of what is essentially the early American frontier of Pennsylvania and Maryland, with all of the mythical opportunity and violent displacement that comes with it.

I’ve also been focused on researching borders because I see the Mason-Dixon Line as this internalized American border. It’s not as immediately present or visible as the U.S.-Mexico border, but throughout it’s history The Line has divided people, it’s a symbol of all the harm America has done to BIPOC groups for centuries. It’s a border that is so present and persistent in America today, but it’s essentially invisible. That visible/invisible dichotomy of border is why the Mason-Dixon Line keeps surprising me. Some days it’s a very clear boundary and other days it melts into the ground.

How does using Large Format impact your art making?

When people talk about using large-format to make work they always speak about the ways its slows down the process of making, lets you compose more thoughtfully. All of that is 100% true for me too, it’s such an amazing way to look at the world. I’ve always felt that life is more beautiful through a ground glass.

But on this project using the large-format camera takes on additional meaning. Putting the camera on a tripod connects me to the process of surveying and lets me grapple with the fraught power dynamics at play: who gets to know, and therefore control, the land? Even just the act of putting the camera and tripod onto the ground makes me more connected with the earth. When I stand still I can feel the softness and the history underneath me and I am more attuned to the changing patterns of the world around me.

On a more practical note I sometimes rely on the large-format camera as a crutch when I approach people to make portraits. I have found that it is much less intimidating for people to be photographed with a 4×5 than with a modern DSLR!

I love the line in your statement, “When I cross the Line it becomes mythology and I am left searching for a constellation on the ground I cannot find.” How can projects like yours, and maybe photographic work in general, help us face and reconcile our past?

This is a great question! I think photography is a medium based in time while also existing outside of time. This is not to say that photography only deals with the past, but often it turns out that way. Its another of those strange and unsolvable puzzles that makes the medium so fascinating.

With my project Mason & Dixon I wanted to investigate this relationship to time by focusing on anachronisms. It’s something that comes up in Pynchon’s novel, but when we talk about anachronism we get confused sometimes. I don’t mean I am interested necessarily in nostalgia; rather I am looking for moments, people, or objects that exist out of their own place in time. Sometimes the past comes back to haunt the present (re-enactors are great example of this), but the present can also find itself in the past, or the future can jump around. Breaking down the linearity of time is something I really believe in. As a result my pictures can take on a “timeless” quality. Initially I saw this as a flaw but now I see it as an important feature in my work because the divisions (racial, social, cultural, ideological) the Mason-Dixon Line embodies have been around for centuries and we are still living in them today.

To come back around to your question; one of the amazing things about photography is that it lets us touch and grapple and acknowledge the past in a way no other medium can. It brings the dead back to life, it makes time cyclical in a way. Photographs are these open books or portals that are subject to reinterpretation. In many ways I would say we cannot face ourselves before we grapple with our past and vice versa; how could we reconcile with history before we deal with our own understanding of who we are?

Finally, is there a mentor you would like to acknowledge?

There have been so many people who have helped me along this journey! I really feel that in the past few years I have found a community of kind and supportive artists unlike any I could imagine. The professors on my thesis committee, Brian Ulrich, Brian I. Daniels, and Greer Muldowney, pushed me to be better all the time. Others at RISD, Steve Smith, Laine Rettmer, Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, guided and supported me through the whole process.

Additionally, everyone I met at the Chico Portfolio Review last year has been incredibly supportive of this project so I want to thank them for that week.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Mackenzie CalleJuly 31st, 2022

-

The 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Seok-Woo SongJuly 30th, 2022

-

The 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Vicente CayuelaJuly 29th, 2022

-

The 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Daniel HojnackiJuly 28th, 2022

-

The 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Third Place Winner: Alana PerinoJuly 27th, 2022