Photographers on Photographers: Lindley Warren Mickunas and Eli Durst

Over the last two weeks, we are sharing some of our favorite Photographers on Photographers posts. Enjoy! – Aline Smithson

I grew up down the street from a community center. In my memory it’s always empty apart from myself and the other restless teenagers that had nothing better to do than sit around and start trouble with one another. Outside there would be epic fights between girls over boys and boys over girls. My friends and I would carve into picnic tables the names of our crushes including the middle school security guard who was probably in his 30s. I think his name was Ken.

Eli Durst paints a very different picture of a community center. His is a place that is full of people and mythical happenings, a place that is otherworldly instead of too real as in my experience. Sometimes while looking at Eli’s images I like to pretend that the events unfolding in them actually occurred in my community center. Perhaps I was just never aware because they transpired behind doors I had never entered, like in dreams where you discover a magical room that you never knew existed in an intimately known house. I asked Eli if he would talk to me about community, performance, and photography. I was pleased he said yes.

Eli Durst, b. 1989, Austin, TX, USA studied American literature and history at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. Upon graduation, he moved to New York City where he worked in the photography industry for three years, assisting street photographer Joel Meyerowitz and training as a professional fine art printer. Durst then attended graduate school, earning his MFA from the Yale School of Art in 2016 and receiving the photography program’s highest individual honor upon graduation, the Richard Benson Prize for Excellence in Photography. Durst received the 2016 Aperture Portfolio Prize for his series In Asmara, which examines the postcolonial legacy of Eritrea’s capital city, and a 2017 Aaron Siskind Individual Photographer’s Fellowship Grant. His first monograph, The Community, is forthcoming with Mörel Books. Durst also makes commissioned editorial work, with his images appearing in The New York Times and Wallpaper Magazine.

Eli Durst: The Community

The fundamental concept guiding my work is the idea that every photograph is both a perfect document and a complete fiction. I seek to blur the line between documentary tradition and conceptual practice, taking subjects that are often represented in a documentary style and infusing them with an ambiguity and strangeness that asks the viewer to reconsider their understanding of reality and its relationship to the truth. I use black-and-white photographs to construct an alternate reality that bears an uncanny resemblance to our own, thereby defamiliarizing the everyday and commonplace.

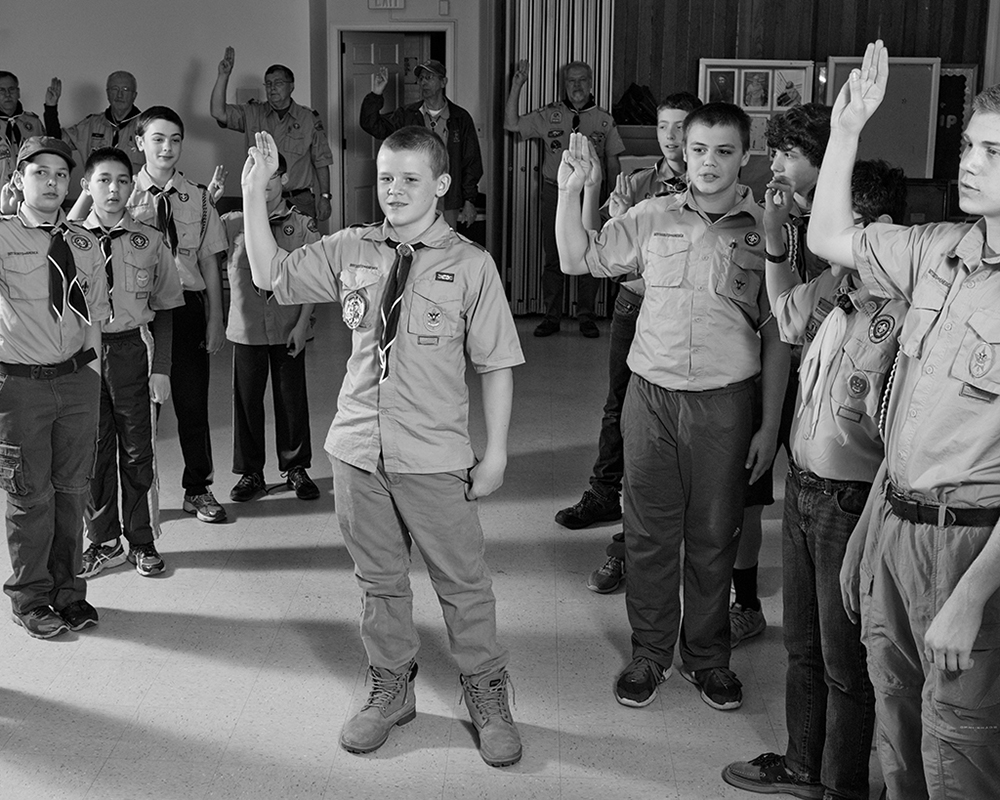

In this body of work, titled The Community, what began as an initial desire to photograph the insides of church basements quickly expanded into a much broader series examining the fundamental search for community in America. The activities depicted range from Boy Scout meetings to New Age spiritual practices to corporate team building exercises and were all made in multipurpose community spaces that are ubiquitous throughout the United States. I became intrigued by the way one activity bleeds into another, creating a symbolic space of communal introspection. Put simply, these photographs are about the search for purpose and meaning in a world that both demands and resists interpretation.

Lindley Warren Mickunas is a Chicago-based photographer, editor, and curator. She is the founder of various publications including The Ones We Love and The Reservoir, a collective editorial project on the politics of image making. Additionally, Warren Mickunas has curated international exhibitions and self-published books and magazines. She is an incoming MFA Photography candidate at Columbia College Chicago and a Curatorial Assistant at the Museum of Contemporary Photography. Most recently, she was published in Heavy III, appointed as a mentor for VSCO Voices, and commissioned by Topic for Federal Project No. 2.

Lindley Warren Mickunas: Maternal Sheet

Maternal Sheet employs the use of intuitive process and various reinterpreted psychodramatic methods to examine violence placed upon the female body, attachment theory, intergenerational transmission of trauma, and motherhood—all within the framework of my family history.

Lindley Warren Mickunas: I would like to begin by talking about the connection between performance and The Community. More specifically, I’m curious about how your photographs might speak to something such as Judson Dance Theater, which was formed by a group of choreographers in a church basement. The Community also began in a church basement, which is perhaps why this specific group comes to mind. Nevertheless, like Judson Dance Theater, it is clear that you have an interest in looking closely at everyday movement and gesture in a way that pulls them out of mundanity. What is your relation to performance art? Is it something you think about in your practice?

Eli Durst: I should make it clear that I am, in no way, an expert on performance. But what I like about something like Judson Dance Theater is the inherent surprise and unpredictability in improvisational work—the strange dynamism that comes from simply putting people together in a room. This is definitely a quality that I’m interested in photographically. Working on “The Community” over the last several years, I’ve come to understand the importance of process. I’m most satisfied with a photo when it feels like a discovery. When a moment or interaction is generated that I couldn’t have imagined or preconceived. So much of the best photography, in my opinion, is born out of chance, or at least catalyzed by it. In his essay “Photography is Easy, Photography is Difficult,” Paul Graham uses a Thomas Pynchon quote from V that I love: “life’s single lesson: that there is more accident to it than a man can admit to in a lifetime, and stay sane.”

Also, from an aesthetic point of view, I love the look of those vintage, black-and-white documentary photos from performances by Yayoi Kusama, Marina Abramović, and Vito Acconci. There’s such an immediacy and lack of pretension to them. I want my photographs to be visually compelling in their composition and use of light, but I also don’t want them to lose their directness, their “realness.”

It’s funny that you previously mentioned dramatizations and reenactments on cheesy crime shows. Whether it’s community theater or historical reenactors or some sort of experimental therapy, I’m fascinated by the idea of trying to embody another reality or state of mind, trying to summon something immaterial into existence. I’m interested in how this can push up against the limits of photography; the thrill and futility of trying to represent a mental or metaphysical state when all photography does, in a literal sense, is describe the surface of things. But at the same time, the photographic image is inherently about conjuring another world out of our physical reality, so in that sense it’s the perfect tool for this pursuit. In Susan Sontag’s essay “In Plato’s Cave,” she writes that the “ultimate wisdom of the photographic image is to say: ‘There is the surface. Now think—or rather feel, intuit—what is beyond that, what the reality must be like if it looks this way.’ Photographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation, and fantasy.” (Sontag 23)

How important is your personal history in the creation and/or reading of your work? How much do you want people to know?

LWM: Personal history informs everything. Just as in Plato’s allegory of the cave that Sontag points to, we all perceive things based off of what we have been exposed to and what we choose to believe. I don’t want to reveal too much and thus deprive the viewer of one of the most powerful aspects of art, which is that through looking at it one can go through a process of personal divining and find within it what is true for themselves.

What is this like for you? How do you decide what to say and what not to say about your work?

ED: It’s a tricky question. On one hand, the ambiguity that I want my photos to have naturally prompts questions about what the viewer is looking at and why. I want to give people enough context to appreciate the work but at the same time, as you said, providing too much information can narrow the range of interpretations—too much explanation can be reductive. I’m a believer in the Depeche Mode’s credo, “Enjoy the Silence.”

Which artists, of any medium including filmmaking, have had the biggest influence on you and why?

LWM: I was always interested in art as a child but my family never went to art museums. However, I started going to them frequently as a teenager, which no doubt changed my life. When I was 16, there was a traveling exhibition curated by Helen Molesworth that came to the Des Moines Art Center called Work Ethic. This was the first time I recall seeing work by artists such as Acconci, Martha Rosler, Chris Burden, Allan Kaprow, and—who really blew me away—Eleanor Antin. In the exhibition was her Carving: A Traditional Sculpture. I had never seen the female body portrayed with such agency.

Around the same time, I saw Jane Campion’s An Angel At My Table and Sweetie. Similar to Antin, these movies carried a specific weight as they were made by a woman and spoke to a particular female experience. Fat Girl by Catherine Breillat and Vagabond by Agnes Varda also made a huge impression on me. A whole new world was opening while I was watching these films, visiting the art center, and stumbling upon books such as Sophie Calle’s Did You See Me?.

I’d like to ask you the same question, about your artistic influences. Also, I read that you originally wanted to study film in college. Have you made film or videos in the past?

ED: I went to college thinking I wanted to study film—it was actually a major reason that I wanted to go to Wesleyan. Even though I eventually dropped it as I became more interested in photography, I still love film and feel as influenced by it as I am by any photography or other fine art. I was completely obsessed with Stanley Kubrick as an adolescent so I feel like that will always be a huge influence—in the way that I feel like I’ll never really love a band as much as the ones I listened to in high school. I’ve always loved the directors who are able to experiment on American cinema from within the Hollywood system, like Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee, Terrence Malick, Steven Soderbergh, Richard Linklater, and PT Anderson among others.

I’m also super interested in documentary film and the ways in which they can blur the line between truth and fiction, which is a concern deeply connected to my own photography. I love filmmakers who subvert our understanding of reality—people like Errol Morris, Werner Herzog, Joshua Oppenheimer, and Michael Apted, whose “7 Up” series is maybe the most powerful piece of art I’ve ever seen.

(Side note: When I was working on my series In Asmara, which was an exploration of the Italian colonial legacy in Eritrea’s capital city, I used post-war Italian cinema as a jumping off point—directors like Antonioni, Fellini, and Rossellini became my visual reference point.)

Despite this, I’ve never seriously made any films or videos. I’ve spent so much time developing my photographic voice that the thought of taking on a new, albeit related, medium with different properties—like sound, camera movement, duration—is really intimidating. But it’s something I look forward to trying and playing around with in the near future.

I’m curious what your process is like, if you’re willing to talk about it. How do you conceive of your images, i.e. what do your ideas come from, dreams, literature, lived experience? Moreover, how much do you refine ideas as you work on them and translate them into photographs? How has the transition from color to black & white been for you and why did you switch?

LWM: I’ve always really appreciated what Agnes Martin said about process:

“Every day for 20 years I would say, ‘what am I gonna do next?’ That’s how I asked for the inspiration. I don’t have any ideas myself. I have a vacant mind, you know; in order to do exactly what the inspiration calls for. And I don’t start to paint until after I have an inspiration. And after I have it, I make up my mind that I’m not going to interfere…

The worst thing you can think about when you’re working—at anything—is yourself. If you start thinking about yourself it stands right in the middle, in front of you, and you make mistakes.”

When I’m lucky images come to me while I’m showering, driving, or walking. It’s then that I have no distractions other than the simple task at hand. Duration is important. For example, the longer I walk the more my mind can quiet. I keep an ongoing list of images and over time other facets of the image show themselves: who, where, when, etc. All of these things are naturally informed by my lived experience and literature I read.

When I began making these photographs, I was mining heavily from my childhood and setting up reenactments. Black and white is a useful tool when considering the past. Artificial light in order to create a greater sense of lightness and darkness has also been instrumental as I’m thinking about the shadow self. I came to realize that I must tap into that aspect in order to move forward in my life.

I want to circle back a bit. You just brought up truth and fiction and earlier talked about an interest in the attempt to move into an alternate reality as a means to beckon the immaterial into existence. Or, if I stretch it a bit, turn the invisible that is often perceived fictitious into a tangible and visible truth. You mentioned, with Sontag’s quote, that photography is an exciting and paradoxical medium to explore these things, but I would love to hear you elaborate on your interest in the space between truth and fiction, the tangible and the intangible, the seen and the unseen. What do you think these things can tell us about our current reality?

ED: The gap between fact and fiction is a big part of my work. It’s why I’m particularly interested in borrowing from the language of documentary photography—it has such a strong connection to our idea of the truth or reality, even if we know photography can’t possibly be objective. Many of my images are made within a very documentary framework—candid photos of people participating in various activities—but I’m interested in how the truth can be stretched or distorted when juxtaposed with images from completely different groups or activities—a sense that all these things could be happening simultaneously in an imagined community center. I’m interested in how the space between the photographs can create confusion and ambiguity, pulling the images into a more fictive, directorial space, blurring the line between reality and fantasy.

I’m curious to get your thoughts on this as well.

LWM: One thing that comes to mind is how in-between spaces can be very fertile ground. It’s similar to why so many artists are interested in liminality. There is a lot of power in being removed from what you believe to be true. It is in this state of unknowing—where answers don’t easily reveal themselves—that real transformation of identity can take place.

What is it that prompted you to investigate community activities?

ED: I was drawn to community centers for several reasons. The first was purely practical. I had been photographically almost exclusively outside in natural light and when I started making the photos that would become The Community, it was the middle of a really cold Connecticut winter and no one was outside. I knew if I wanted to keep making images of people, I would need to move inside. Originally, my idea was to limit myself to church basements and the various activities that took place there. (Church basements struck me as a deeply charged and prototypically American space.) But at the time, I was dealing with some serious illnesses in my family and I think that pulled the work towards a more spiritual or aspirational activities—groups of people coming together in search of meaning or purpose or some form of self-realization. Also, by this point, I was really interested in the aesthetics of these types of community center spaces. They’re utilitarian and functional, meant not to be glamorous but practical. They’re somehow both extremely generic while also being comfortingly familiar. They’re so ubiquitous and so completely ignored.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Jason Lindsey in Conversation with Areca RoeApril 21st, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: J Wren Supak in Conversation with Ryan ParkerApril 20th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Josh Hobson in Conversation with Kes EfstathiouApril 19th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Leonor Jurado in Conversation with Jessica HaysApril 18th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Sarah Knobel in Conversation with Jamie HouseApril 17th, 2024