Sant Khalsa: Crystal Clear/Western Waters

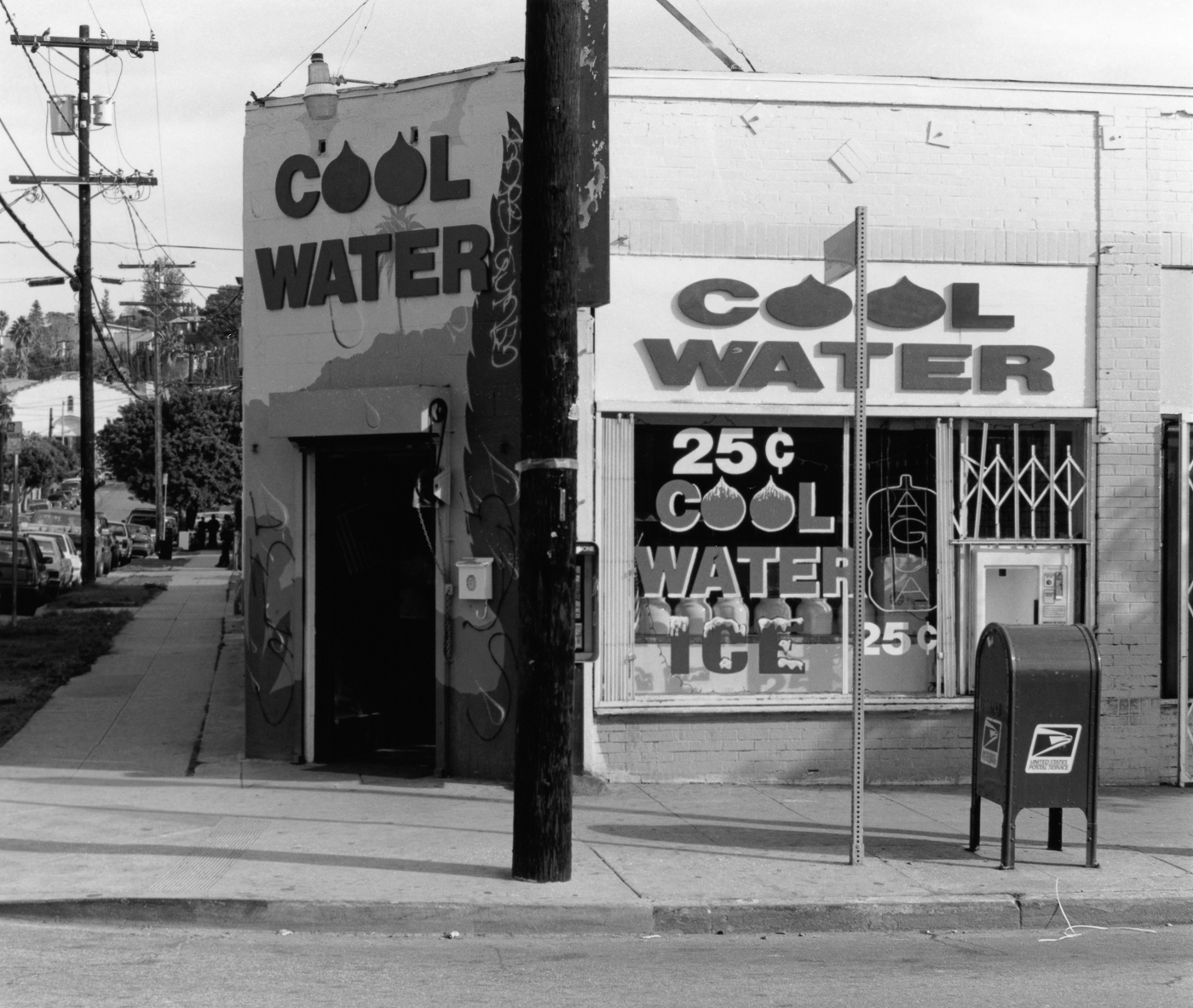

© Sant Khalsa, Cool Water, Los Angeles, California, from “Western Waters” series, 2000-2002 and “Crystal Clear || Western Waters“ book (Minor Matters, 2022)

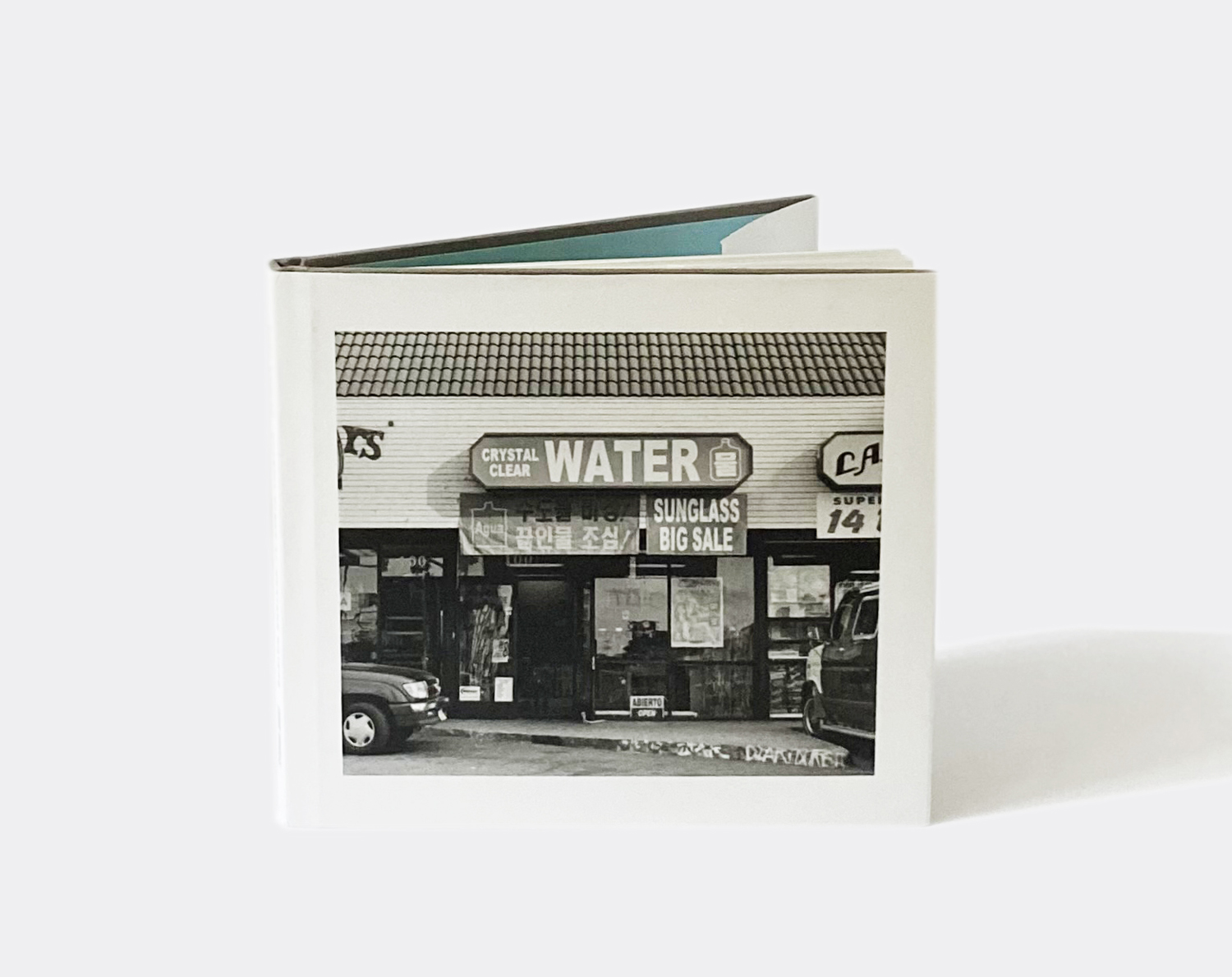

© Cover of Crystal Clear || Western Waters, Photographs by Sant Khalsa with Foreword by Ed Ruscha, Minor Matters, 2022

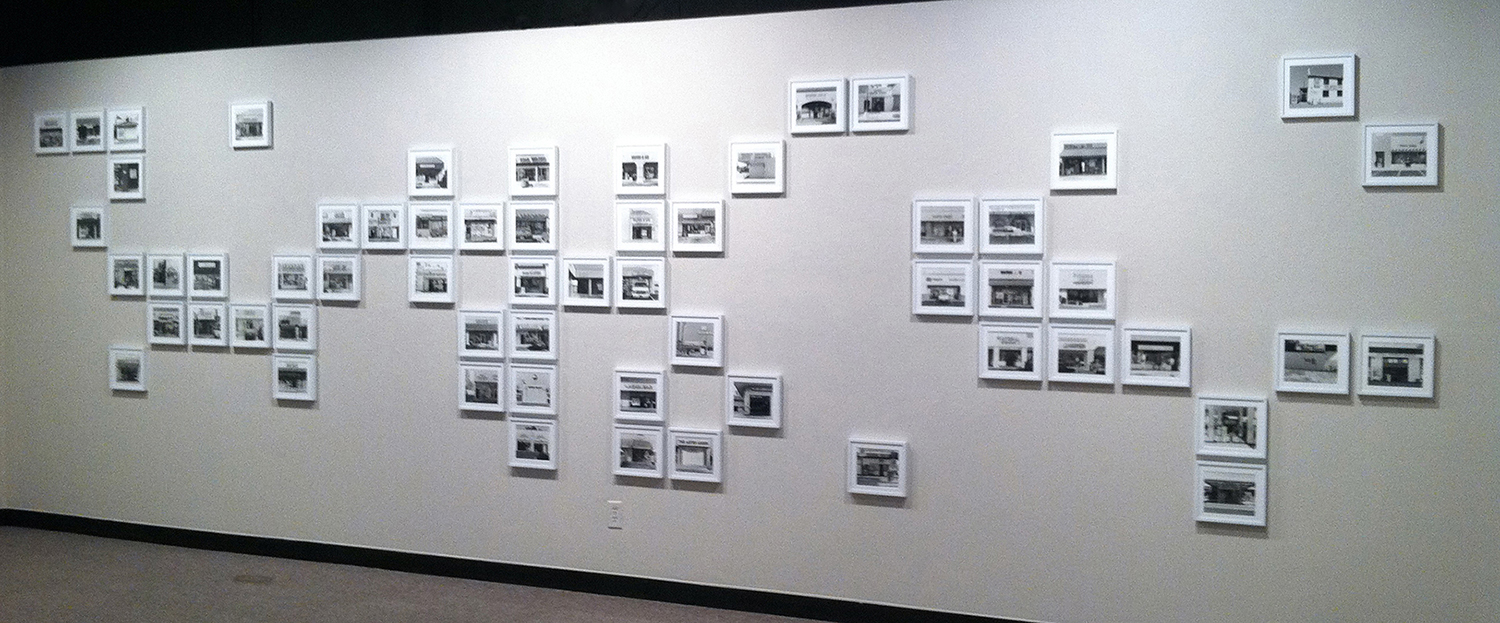

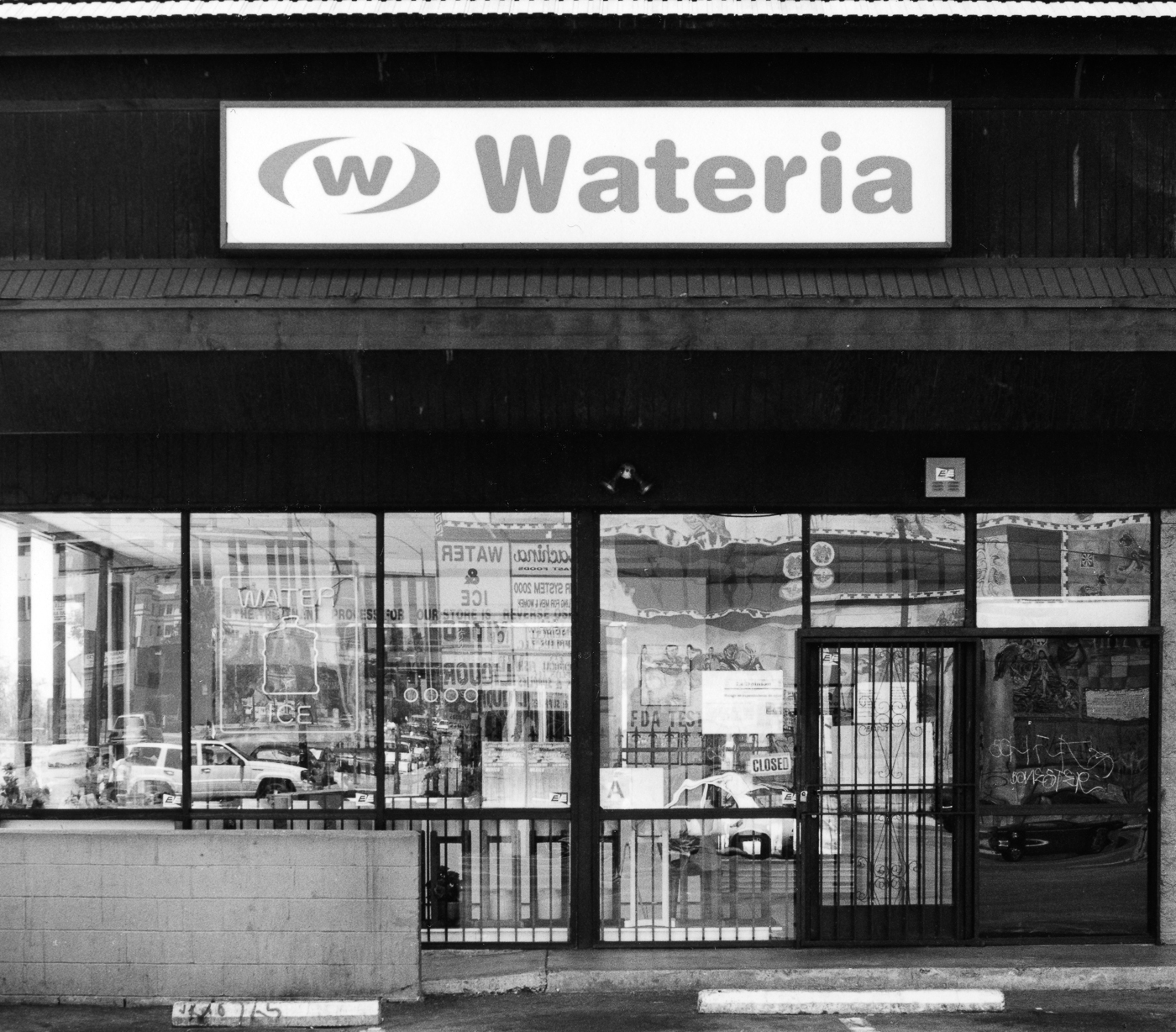

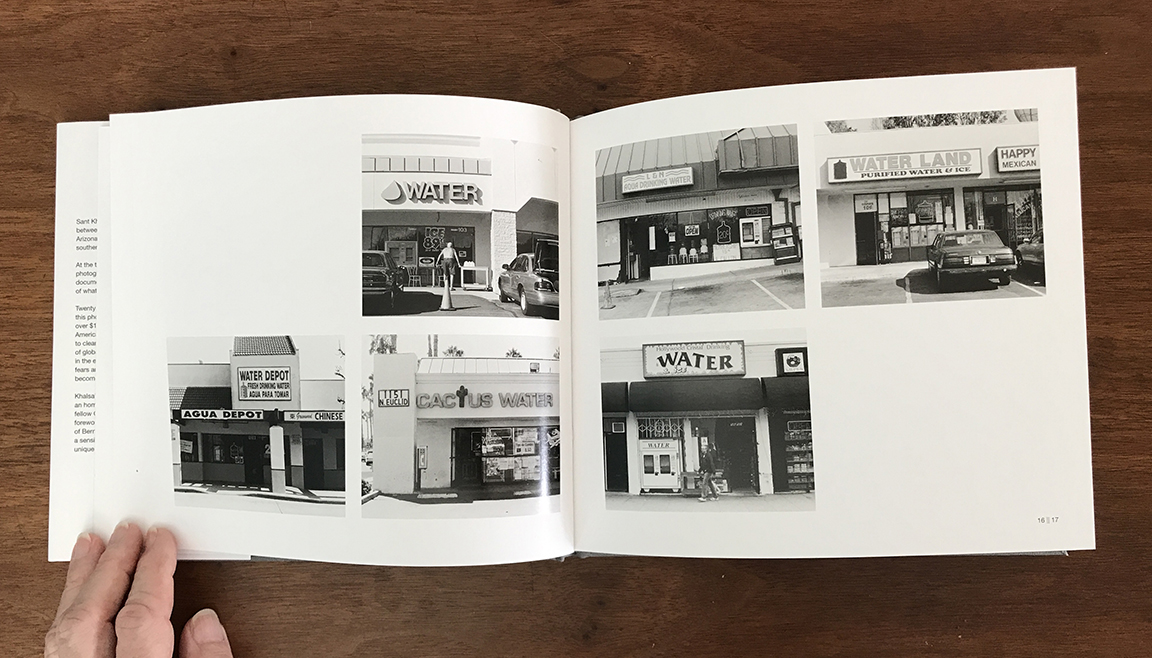

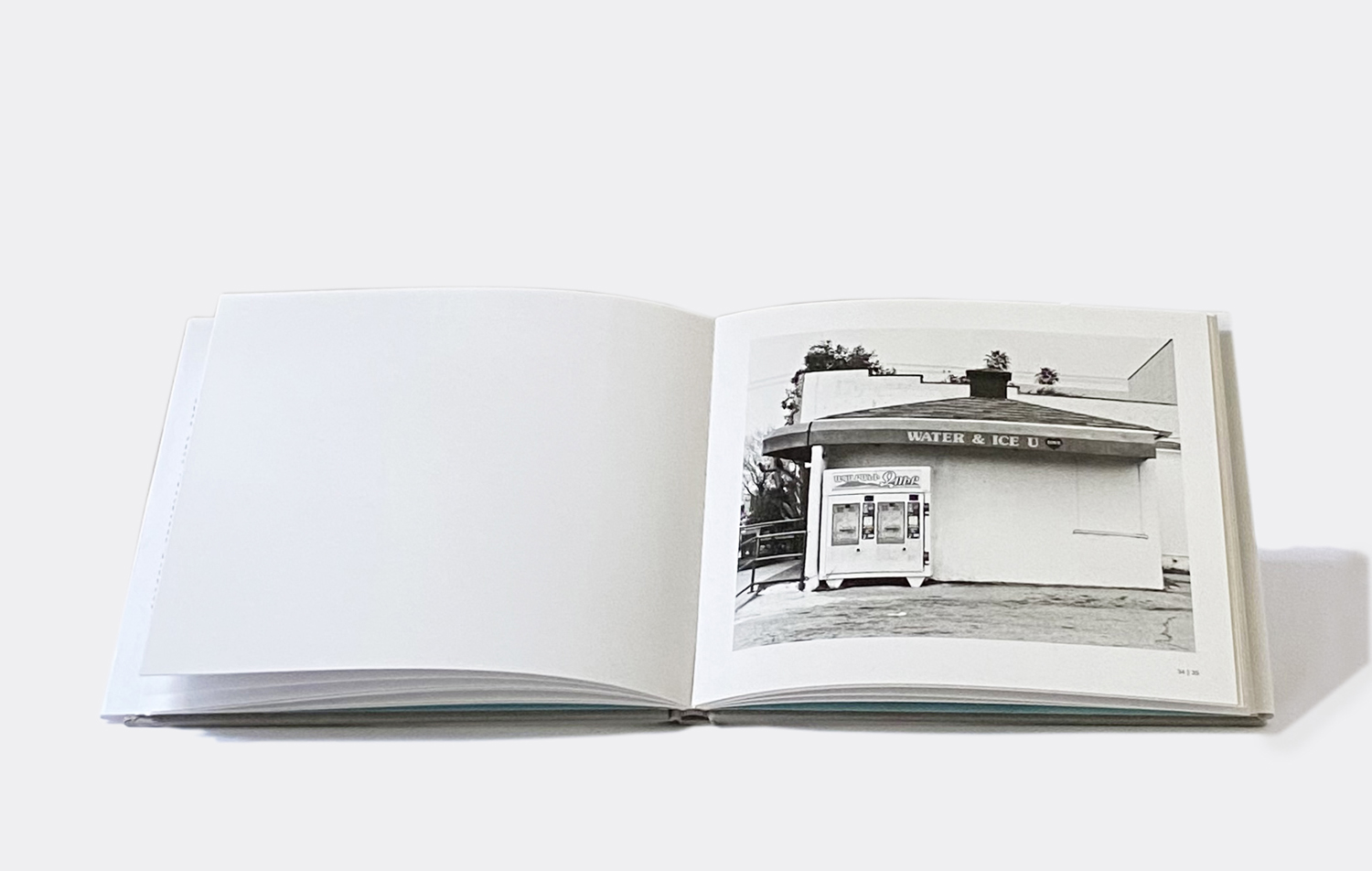

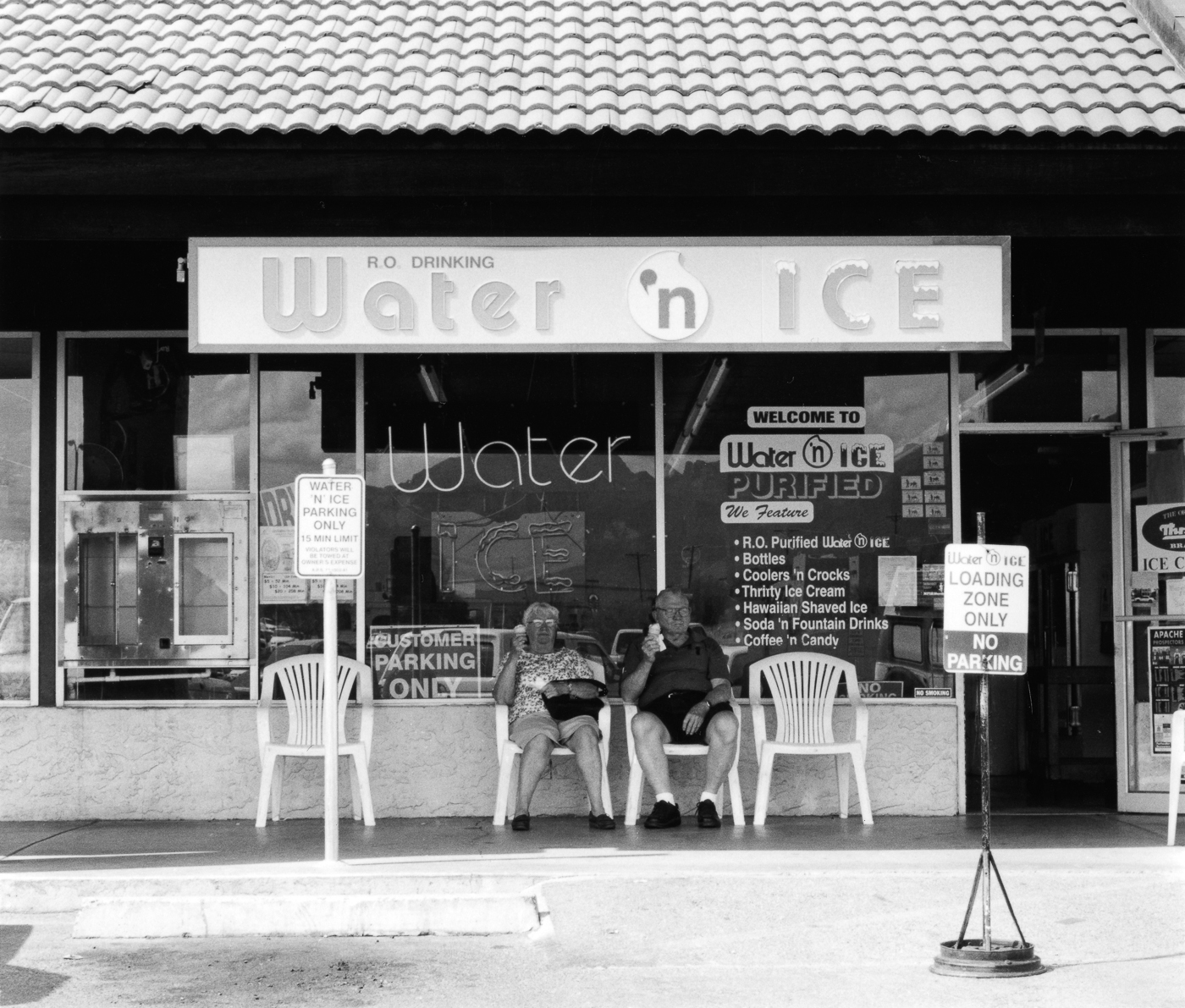

In her latest monograph, Crystal Clear || Western Waters published by Minor Matters, Sant Khalsa explores the commodification of our most basic resource through the proliferation of water stores that came to prominence in the 1990s and early 2000s. These retail points-of-sale typically sold reverse osmosis filtered water in strip malls across the urban, suburban, and rural American Southwest. The series captures the varied storefronts in four Western states, including their quintessential signage, revealing the paradoxical nature of these sites as both necessary and absurd constructs of our capitalist society. Khalsa’s book is a compilation of well-reproduced silver gelatin prints that evokes both nostalgia and criticism and serves as a thought-provoking commentary on the fabrication of human desire and its impact on the environment.

The following is a transcript of a conversation between Tracy L Chandler and Sant Khalsa.

© Sant Khalsa, Wateria, Los Angeles, California, from “Western Waters” series, 2000-2002 and “Crystal Clear || Western Waters“ book (Minor Matters, 2022)

TLC: I grew up in the California desert during the 90s. These photographs of water stores seem to come straight out of my personal memories and are why I was so interested in talking with you about this book. I am curious about your background as an artist and an activist and what was the inspiration that led you to create this specific body of work?

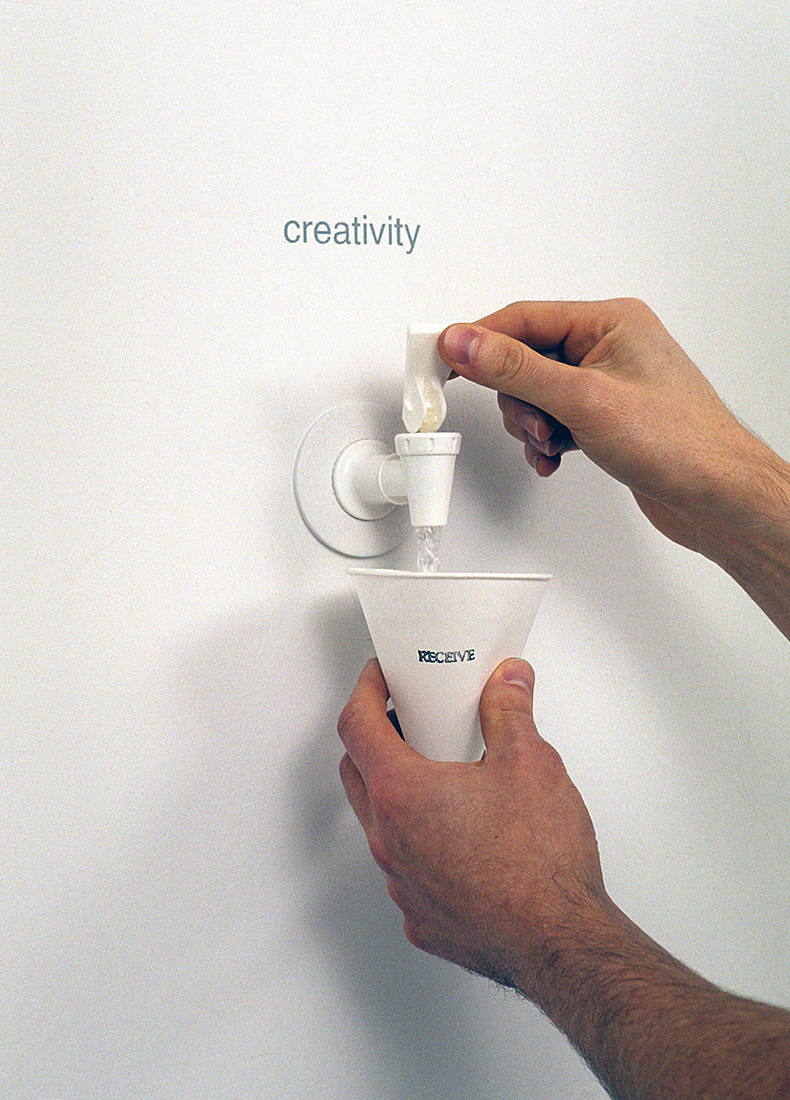

SK: I’m going to show you an installation piece that I worked on in 1995 called The Sacred Spring. It has nothing to do with photography. It has to do with experience, the single most important and basic experience that we do every single day in our lives, drinking water. I had been researching and photographing water in Southern California for years and was invited to participate in an exhibition called Muses at the Armory Center for the Arts in Pasadena. The myth of the muses is that they were female goddesses born from a spring that men would look to for inspiration and creativity. My work, The Sacred Spring, served as a metaphor for nature and for self and for the consumption of what already exists and flows within each of us. For the show, I plumbed a wall with 9 water spigots, each with a word representing a desirable quality – inspiration, abundance, creativity, affection, honesty, intuition, harmony, passion and grace. Visitors would come and take a cup of whatever water qualities they wanted. The whole idea was that people seek things that they want to consume to make themselves feel better. It’s all about this act of consumption and that we take from the natural world. Individuals and groups would engage with the installation saying something like, “Oh, I’m going to drink creativity!” or “I want some grace.” And they thought that each of the waters were different. They would taste the water and remark, “Intuition really tastes different than passion!” But it was all the same spring water.

TLC: This is so simple yet so brilliant. A model of the consumption of nature and the metaphor of seeking to ingest something that is already within us, not just the qualities of inspiration, creativity, and grace but just water, the element itself. Our bodies are made of water.

TLC: This is so simple yet so brilliant. A model of the consumption of nature and the metaphor of seeking to ingest something that is already within us, not just the qualities of inspiration, creativity, and grace but just water, the element itself. Our bodies are made of water.

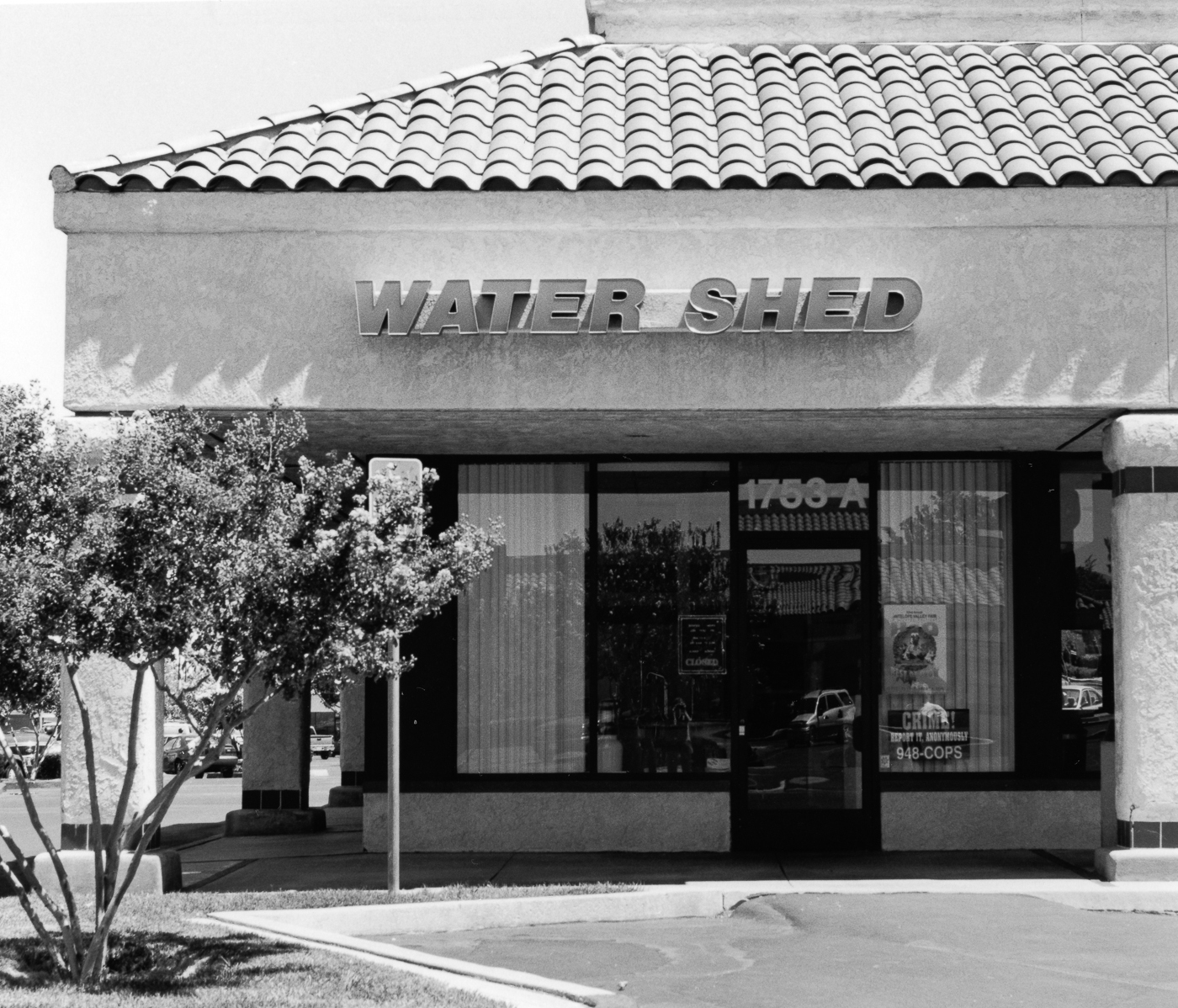

SK: Exactly! It is the most basic of needs. I wanted to explore this further. While I was doing research for another installation project where I created a fake bottled water brand called Watershed, I came across an actual business named Water Shed, located in Palmdale, California. Of course, I was curious, so I drove to the Western Mojave Desert to see what this business was. There I found a retail water store in a strip mall selling reverse osmosis purified water from tap to bottle. Further research showed me there was a growing business of retail water stores throughout the Southwest. I was drawn to the subject because of the apparent necessity, yet absurdity of these stores and the way these venues seek to represent the source of a natural experience. Of course, these stores are merely an entrepreneurial enterprise, a constructed site to provide us, the consumer, with the most essential requirement for life and survival. I thought to myself that many of the ideas expressed in The Sacred Spring and Watershed installation works had manifested in the real world.

© Sant Khalsa, Water Shed, Palmdale, California, from “Western Waters” series, 2000-2002 and “Crystal Clear || Western Waters“ book (Minor Matters, 2022)

TLC: You were definitely ahead of the trend. Water soon became a ubiquitous packaged commodity. Your Western Waters series captures water stores in various locations across the Southwest. Can you talk about the process of selecting these locations?

SK: It took me almost three years, and I actually took a sabbatical from teaching at California State University, San Bernardino to do this project. I traveled around four states, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California. I would go to the water stores and photograph the outsides all from the same perspective. I was thinking about the work of Ed Ruscha, and specifically his 26 Gasoline Stations. I was thinking about how these water stores were becoming like what gasoline stations were back then. A constant feature in our constructed landscape.

© Sant Khalsa, Five Springs Water, Alamogordo, New Mexico, from “Western Waters” series, 2000-2002 and “Crystal Clear || Western Waters“ book (Minor Matters, 2022)

TLC: When I view these images I find myself scanning for details, asking myself “what is the same, what is different?” What made you explore this subject matter typologically?

SK: Beyond Ruscha, I was also thinking of Hilla and Bernd Becher and their typologies of water towers. And yes, in typologies your mind focuses on the similarities and the unique details. The architecture of these stores Is remarkably similar, most often storefronts in strip malls. What varies, are the signage and store names.

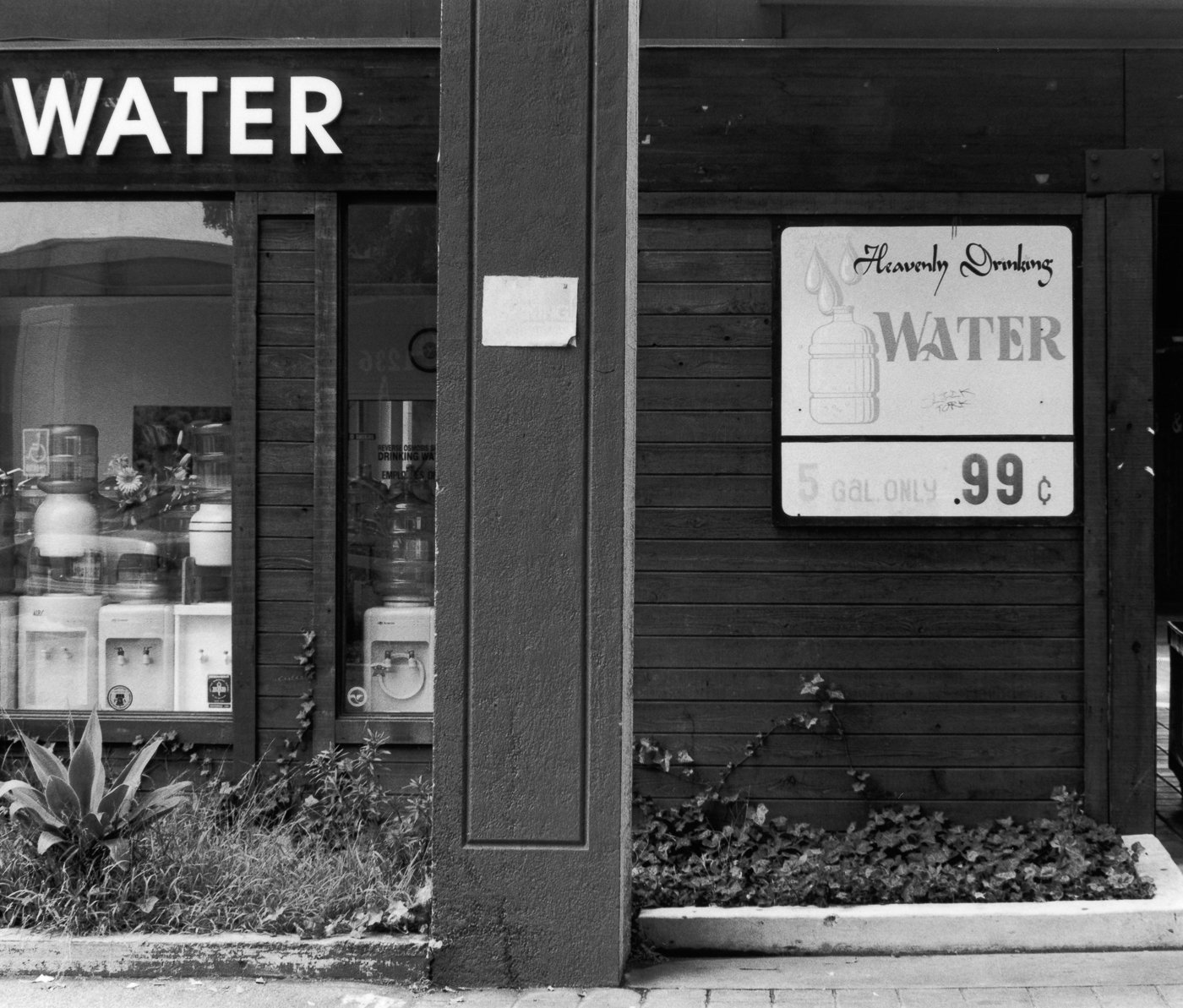

© Sant Khalsa, Heavenly Drinking Water, Glendale, California, from “Western Waters” series, 2000-2002 and “Crystal Clear || Western Waters“ book (Minor Matters, 2022)

TLC: Yes. The names of each store are a prominent part of this series. Words within a picture, verbal concepts, are a specific attribute of some photographs. Not only can they monopolize our attention but also send us on a conceptual thread that a typical landscape may not. I can’t not think of Walker Evans “Damaged”.

SK: I was fascinated with the signage and what it was saying. The store names were often referencing water quality or a theme of nature and a spiritual connection to it. Words like “heavenly” and “paradise”. I was contending with the idea that we were going to these places to consume not only “good” or “pure” water, but to feel like we were closer to nature. One image featuring the store Happy Water has a Honda ‘Accord’ parked in front, emphasizing what we seek, which I think is so interesting.

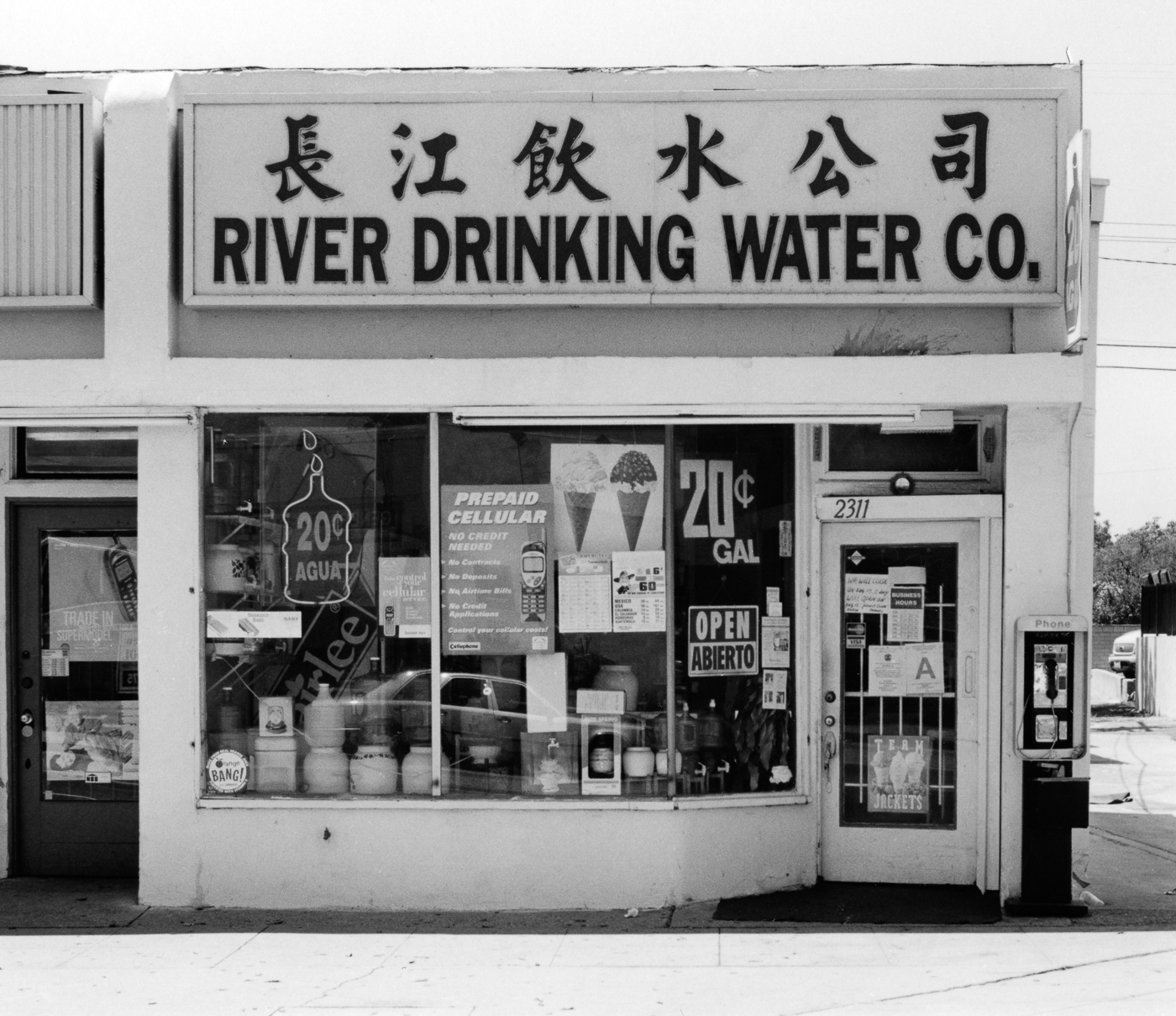

© Sant Khalsa, River Drinking Water Co., Monterey Park, California, from “Western Waters” series, 2000-2002 and “Crystal Clear || Western Waters“ book (Minor Matters, 2022)

TLC: There are other languages represented as well, Spanish, Korean. How does this issue of water seem to crossover with the experience of the American immigrant?

SK: There are a variety of Asian languages. There are some Middle Eastern languages like Arabic. And lots of Spanish signage. One water store I photographed was next to a shop named the Happy Burrito Mexican Restaurant. I thought, if I frame the photograph in a certain way, where you not just see the water store, but you see Happy Mexican, then it speaks about immigration. And it speaks about the fact that people come here because there’s clean water and land and space and opportunity. So many of these water stores are in immigrant neighborhoods because these diverse communities have come to the U.S. from places where they didn’t have potable water coming out of their taps at home. Going to a water store to buy water is something that they used to do where they came from. So this made perfect sense to have water stores in these neighborhoods and many of them are actually businesses that are created by the immigrants themselves.

© Sant Khalsa, Water Land, Santa Ana, California, from “Western Waters” series, 2000-2002 and “Crystal Clear || Western Waters“ book (Minor Matters, 2022)

TLC: So they’re building these businesses in their own neighborhoods and marketing water to themselves because of the conditions and customs they have come from? But is it necessary? Is it affordable? Is it sustainable? Is this where the practice of this type of consumption reaches into the absurdity claim?

SK: Not completely. When I did this project about 20 years ago, it seemed that the majority of the water that was available in the places where these water stores were was drinkable straight out of the tap. The majority. But there were definitely places where the water in these communities was questionable. The question was whether the infrastructure was still safe. We’ve learned over the last 20 years that infrastructures are failing in the United States. And this is not something that is just happening in immigrant neighborhoods. Look at what happened in Flint Michigan. In my research for Western Waters, the first water store to open was in Alamogordo, New Mexico, where the first nuclear bomb was exploded.

© Sant Khalsa, Water, Mesa, Arizona, from “Western Waters” series, 2000-2002 and “Crystal Clear || Western Waters“ book (Minor Matters, 2022)

TLC: Yes. In some cases, the necessity is definitely there. There are so many complex issues with pollution, infrastructure, and climate change that necessitate expensive and wasteful workarounds for what I see as a basic human right to clean safe water. But there is also a game of capitalist enterprise going on here, a sort of stoking of people’s fears of safety and a corporate capitalization on flawed infrastructure. Just think of the proliferation of plastic bottled water sold by Coca Cola and PepsiCo. These photographs show the birth of that trend and things have only increased exponentially since. But what is also interesting to me, is the feeding of the desire to be pure and natural. That has become part of this economic wellness trend as well. Your photographs point to that desire for connection to nature.

SK: I believe that we all want to be closer to nature, and we all want to have that true realization that we are nature, not separate from it. It seems to be fundamental to the human experience. During the pandemic, a time of great stress and a return to basics, it became very clear that when people were sequestering, the thing that they wanted to do most was to go out into natural environments – forests, deserts and beaches. Unfortunately, most humans see themselves as separate from nature. I have great respect for the relationship Indigenous people have with the natural world. At a lecture given by a Cahuilla artist friend, I asked him a question about something related to nature and he said that there is no word in Cahuilla for nature. There’s no word because it just is. It’s everything.

© Sant Khalsa, Lakes Water, Las Vegas, Nevada, from “Western Waters” series, 2000-2002 and “Crystal Clear || Western Waters“ book (Minor Matters, 2022)

TLC: Can you share with us the journey that led you to merge your passion for activism with your artistic practice? Does one lead to the other or is it a chicken/egg situation?

SK: I see a very strong relationship between what I do as an artist and what I do as an activist, that it’s all very, very connected. In terms of activism, ultimately I believe that the way a person decides to live their life is based on their own experience and awareness. They have to have some kind of epiphany, something that makes them have this realization that I’m nature and therefore what I do, my actions and my inactions not only impact me, but impacts everything around me.

TLC: You have very creative ways of exhibiting, including sculpture and built objects… is the book an extension of that sculptural approach or do you see it as a document performing a different function?

SK: I totally relate to this book as an object in-and-of-itself and as a way to engage a larger audience in a more intimate experience. At the same time, it is also an extension of my installation work. Let me explain. In Western Waters, I photographed over 200 water stores but cut the edit down to 60. In my exhibitions, these 60 photographs are set up on the wall in direct relation to each other geographically. So you’re actually going from Southern California into Nevada, Arizona, then New Mexico. You can follow the pilgrimage along the wall. The book design reflects ideas of the installation grid but is a unique interpretation that focuses on the photo compositions, architecture, store names and signage in book form. Moving through the book is a different journey, concerned with how one can read the photographs and ideas from page to page, as individual images and as groupings together. Each element of the book design including paper, duotone ink colors, gray cloth with silver type on the spine, and water blue endpapers were all thoughtfully selected to produce a beautiful object. And speaking of road trips and journeys, the book is intentionally the exact same size as Robert Frank’s The Americans, the publisher and designer Michelle Dunn Marsh’s brilliant idea.

© Spread from Crystal Clear || Western Waters, Photographs by Sant Khalsa with Foreword by Ed Ruscha, Minor Matters, 2022

TLC: Yes. I noticed that. The legacy of the photographic road trip continues on. Your book follows some of the best in that photobook tradition. How did your collaboration with Minor Matters come about?

SK: I met Michelle Dunn Marsh when she was working for Aperture. That goes back about 17 years. At the time, she was the director of what was called Aperture West, which was a division of Aperture where they were focusing on work in the Western United States. Michelle expressed interest in my Western Waters photographs as a book but it didn’t happen at that time. After Aperture, and two years at Chronicle Books, she started Minor Matters in 2013. Since then we had discussed doing this book multiple times but I just wasn’t ready. And then during the pandemic, she approached me again and said we should do the book in 2022 as it would be the 20th anniversary of the project. I had grown to really know and trust Michelle over these years and knew we were on the same page. This timing made sense to me and the messages are really important to share. More so than ever, at this time in my life, I’m looking at what legacy I leave behind. Books are important to me and a perfect way of sharing my life’s work with more audiences.

© Spread from Crystal Clear || Western Waters, Photographs by Sant Khalsa with Foreword by Ed Ruscha, Minor Matters, 2022

TLC: The opening essay by Ed Ruscha sets up this work so well. He tells a story about stopping for water on a family roadtrip in the 1950s and his father being appalled at having to pay for it. It is such a great narrative depiction of the themes you are contending with.

SK: When working on the book, Michelle asked me if I could have anyone contribute writing, who would that be? I really had to think about it. I said, “You know, the only person I want to have is Ed Ruscha.” And so I reached out to him and he agreed to do it. Five or so years ago I decided to send him a letter with a print from Western Waters as a thank you for his inspiration. He wrote back to me and included a stunning book of his work that had just been published and in the book was a note that said, I’m also sending you this text that I wrote about water. I read it and thought to myself “Oh my god, this is so great!” So we ended up using it for the foreword in the book. It just dovetails so perfectly. I am grateful to Ed for his generosity.

© Sant Khalsa, Water ‘n Ice, Apache Junction, Arizona, from “Western Waters” series, 2000-2002 and “Crystal Clear || Western Waters“ book (Minor Matters, 2022)

TLC: These photographs are over 20 years old now. You have written in the past that these photographs may serve as a historical document for either a fleeting fad or a foundation for what will become commonplace in our society. We know how that turned out. Do you have any desire to photograph the current and future progression of water usage? What are you working on now?

SK: Long before I began work on Western Waters, and since, much of my photographic work has focused on water and watersheds, including forests. I worked for close to three decades on “Paving Paradise,” an extensive photo project about the Santa Ana River and Watershed, which is the largest coastal water system in Southern California. This work was part of the Water in the West Project and is now archived at the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Since retiring from California State University, San Bernardino, where I taught photography for thirty years and moving to Joshua Tree, I have embraced the vast, beautiful and fragile landscape of the California desert as my subject. I’m exploring and photographing many sites including the salt mines at Bristol Dry Lake near Amboy, California and the geothermal fields on the southern end of the Salton Sea, where steam is harnessed to generate power and lithium is also extracted. The unique and iconic Joshua tree and their habitat have been a strong interest of mine that I have photographed on and off since the 1980’s. Much of the last two years I’ve been engaged in indepth curatorial research for a multidisciplinary exhibition with a book and community programming titled “Desert Forest” about the plight of Joshua trees, which are threatened by climate change due to increasing temperatures and decreasing rainfall, as well as development and industrial solar and wind energy. The exhibition will be at the Museum of Art and History (MOAH) in Lancaster, California from September 7 to December 29, 2024 and will include a variety of art mediums including photography, painting, drawing, sculpture, video, and installation along with natural history, science, indigenous knowledge, and much more. I am thrilled that the project is part of the Getty Initiative Pacific Standard Time 2024 – PST ART: Art and Science Collide. Making photographs remains integral to my art and meditation practice – being still, alert, and present in moments of mindful observation, as a means to explore the place where I live and visually express my ideas and experiences. It is always my hope that my artworks (and curatorial projects) create a contemplative space where one can sense the subtle and profound connections between themselves, the natural world and our altered environments – a watershed experience.

© Sant Khalsa, Good Water, Montebello, California, from “Western Waters” series, 2000-2002 and “Crystal Clear || Western Waters“ book (Minor Matters, 2022)

Crystal Clear || Western Waters by Sant Khalsa is available for purchase through Minor Matters.

Sant Khalsa is an artist and activist whose artworks derive from a mindful inquiry into complex environmental and societal issues. Her photographic, mixed media, and installation works are widely exhibited and collected. She is a Professor of Art, Emerita at California State University, San Bernardino and lives in Joshua Tree, where she is the Founding Director of the Joshua Tree Center for Photographic Arts.

Follow Sant Khalsa on Instragram

Minor Matters is a collaborative publishing platform, making books through the engagement of their international audience. Minor Matters highlights underrepresented voices in contemporary art and preserves our present for the future through publishing their work.

Follow Minor Matters on Instagram

Tracy L Chandler is a photographer based in Los Angeles, CA.

Follow Tracy L Chandler on Instagram

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026