Xuan-Hui Ng in Conversation with Samuel Feron

I’ve been a huge fan of Samuel Feron’s work for some time now. I am spellbound by his creative interpretation of nature. His collections have redefined my understanding of what a series should consist of. He is a thoughtful photographer, often expressing his concern about photographers’ impact on the natural environment.

You can imagine my delight when Samuel, whose work is a huge source of inspiration, agreed to accept my request for an interview.

Samuel Feron has been photographing landscapes worldwide for 15 years, with a predilection for deserts, and cold and volcanic regions. He has received awards in several international contests including Fine Art Photography Awards (2015, 2016), the Prix de la Photographie de Paris (2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015), International Photographer of the Year (2016), International Photography Awards (2012, 2013) and others. He was an international jury member for Px3 in 2016 and for IFAP in 2017.

In 2015, he founded Terra Quantum, a project to compile the most beautiful images of our planet. Images are reviewed by jury members from around the world before publication.

You can read his previous interviews with Terra Quantum’s Beata Moore and Dodho’s Maria Olivia.

Instagram: @samuelferon

Why do you photograph nature?

I live in a crowded country, on a planet where there are people everywhere. As technology pervades big cities, we lose the essence of life. I photograph nature because I need to escape our common way of life. The desire to explore is a strong motivation even though 99% of the Earth is surrounded by satellites which allow us to see any almost any part of the planet without leaving home. Despite our outsized influence, nature is much more powerful than we are. I would feel trapped if I did not get out of my man-made environment and plunge into the immense natural spaces of the world.

I am attracted by things in nature that remind us how weak we are. That’s probably the reason why I prefer photographing remote places such as deserts, volcanos, glaciers, etc.

You mentioned in a 2017 interview with Beata Moore for Terra Quantum Territories that you realized your intention to show the world like a reporter and your focus on aesthetics is “compatible to a certain extent only.” Could you elaborate on that?

What I meant was the more I tried to represent the world, the less free I felt to express an artistic point of view. A witness is not an artist. In some cases, what I see remains the main subject and my job is to personalize this subject, using techniques such as contrast, (de)saturation, etc. In other cases, I use what I see to create an image or a series. The subject is just a pretext for creation, so I don’t limit the techniques I use.

I have not made “photomontages” (taking part of an image and placing it in another image). But maybe I will in the future. Let’s see.

How would you describe your aesthetics, your signature?

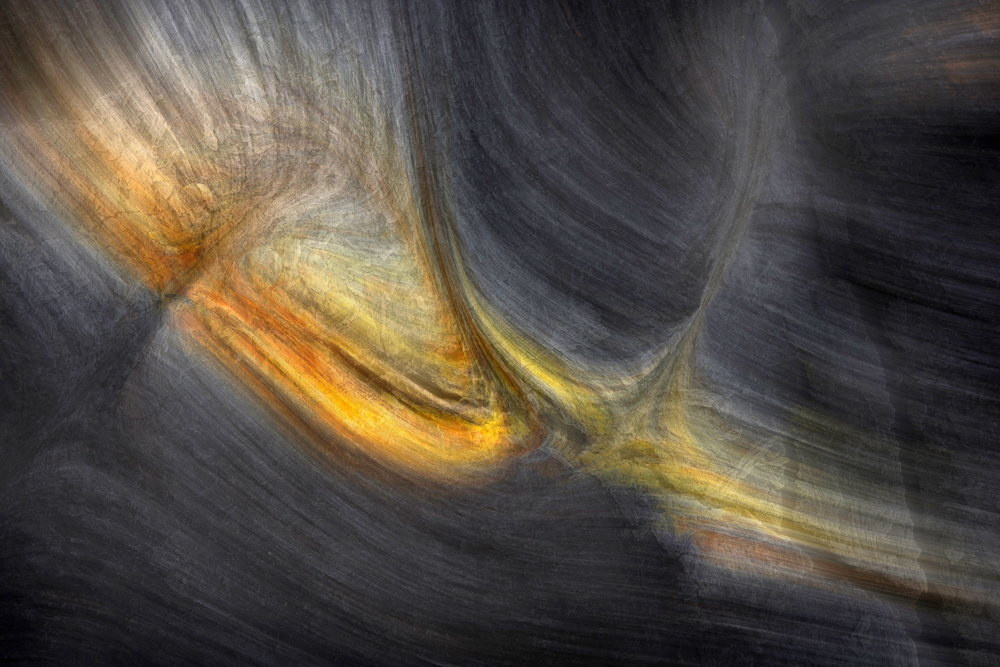

I am not sure I am best placed to answer this question. I try to make series that are different from each other. For instance, the series “Esquisse” plays with subtle lines and light, where color is almost non-existent. In contrast, strong colors are the key in the series “Jungle,” featuring plants and flowers, and guide the viewers’ gaze. In the series “Matter and Oblivion,” I use triptychs to create dynamism and express how matter evolves. Honestly, I find it difficult to identify a common feature or a consistent signature.

The images in each of your collections are distinct but the colors and style are cohesive. How do you determine the theme or concept of a project? Do you decide after having seen the place and while you are photographing, or before you have even visited?

It is a difficult question to answer. I don’t have general rules, themes, or techniques. In some cases, I have pre-conceived ideas. For example, I might imagine building a series based on light striking dry and dusty rocks in remote mountains. I find this way of photographing motivating because the constraint forces me to concentrate. I have remarked before that having constraints allows me to achieve a more elaborate, creative, and original result because it demands reflection and planning. When I am in the field, I strive to look for such spots to produce a large set of images. Then, I choose the images to compose the series. The main difficulty of the second part is to avoid having too many redundant images while remaining consistent. It’s important to reflect what makes an image redundant and/or the criteria for a series.

In other cases, I don’t have a concrete idea about a future series. I trust my intuition and try to stay confident that I will get enough images to build a series later. My primary concern is remaining sufficiently open when I photograph. In such cases, each photo may be the start of a new series. At home, I browse through my photos until I find a “common denominator,” which could be color, symbol, pattern, idea, or concept, etc. This process can take a long time and have no end! I have started series that are still in progress and I am not sure I can finish them. Inspiration sometimes ends after two or three photos; I don’t know why.

You said before that “replicating what I have previously done in other places generally appears incorrect.” Could you explain?

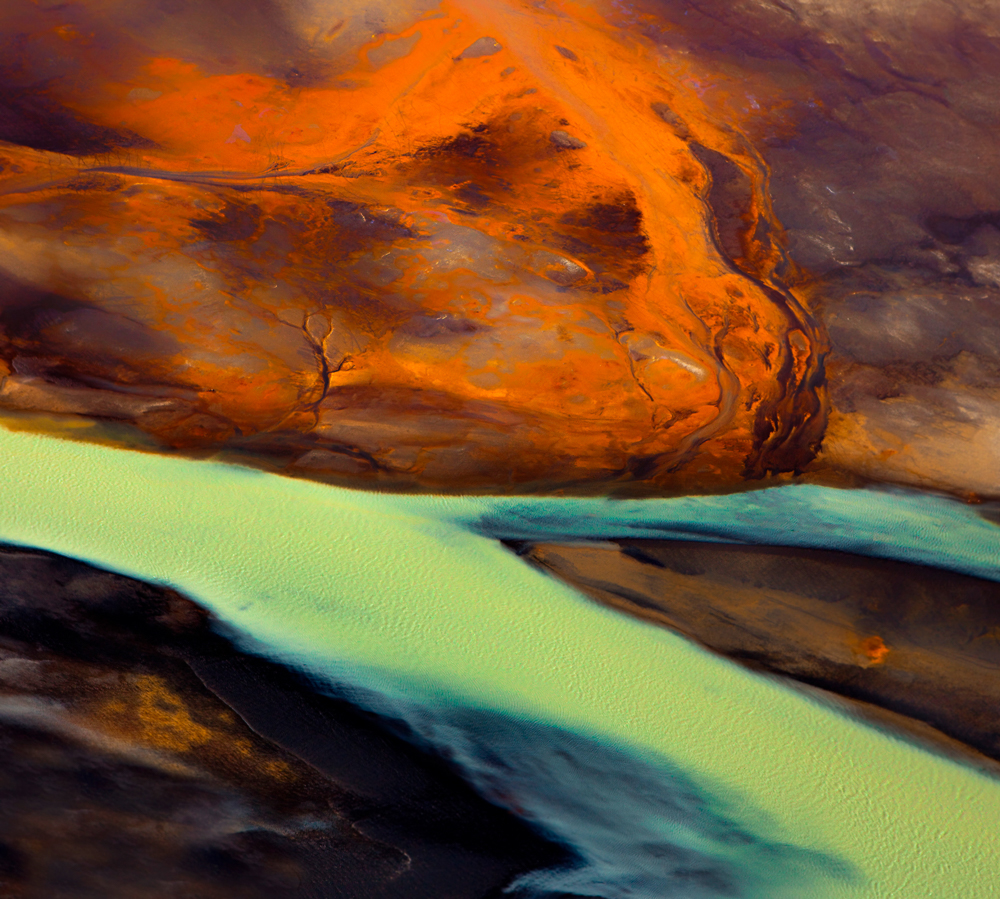

I meant that each country has its own aesthetics and atmosphere. Weather and time are intimately linked to the colors in the landscape. For instance, Bolivian lagoons show amazing colors under a blue sky in the middle of the day but they lose color at sunset when the light grows weaker. So, the beauty of the lagoons is intimately connected with the weather.

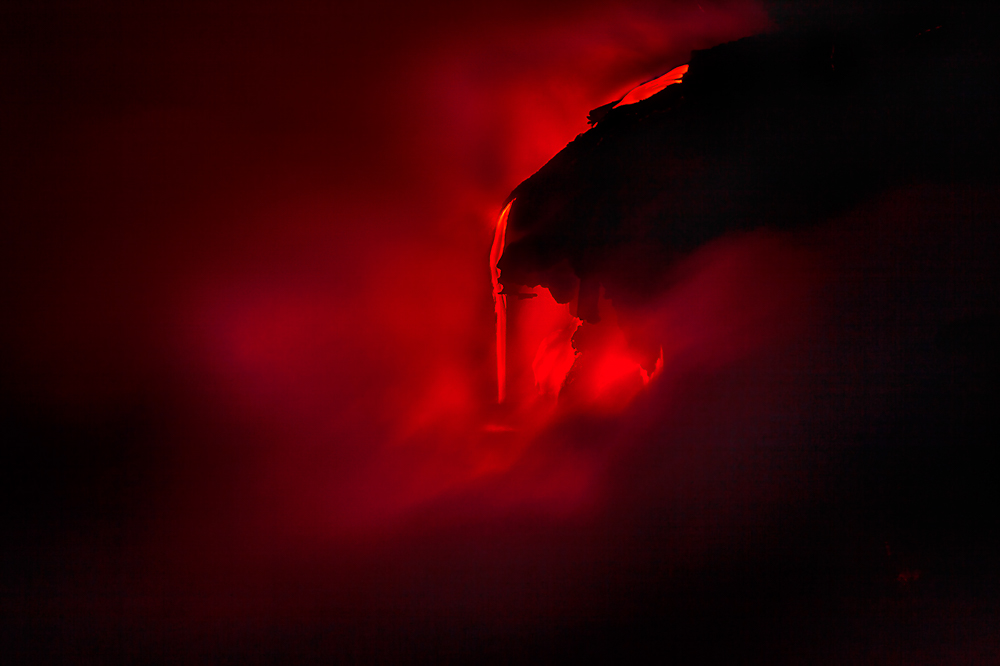

By contrast, in Iceland, most of the magic is based on the atmosphere created by fog, wind, and clouds. Taking a picture in the highlands when the sky is clear doesn’t generally lead to anything interesting.

That’s why it is important to adapt your style to the local character. If you are someone who doesn’t like bright light and clear sky and plans to go to the Atacama, then you need to change your mind frame, adapt your technique, and modify your project. Otherwise, you may be disappointed trying to achieve the results you expect. Moreover, you may miss the essence of the region.

When photographing black and white images, do you pre-visualize the scene in black and white or do you convert to black and white if the scene does not work in color?

That depends. In some cases, I have no interest in the colors of a scene or feel that color is distracting and plays a superfluous role. I know before taking the picture that I will convert it to black and white. Then I focus mainly on shapes, mood, and graphics.

In some other cases, I decide to convert to black and white after having taken the picture. The series “Chaos” is an example. It could work in color, but I wanted to express the effect of time passing, starting from simple shapes and moving to elaborate, fractal patterns, when the distinction between past and future is not relevant. I felt that using different shades of gray was an interesting way to illustrate this effect.

When photographing black and white images, do you pre-visualize the scene in black and white or do you convert to black and white if the scene does not work in color?

That depends. In some cases, I have no interest in the colors of a scene or feel that color is distracting and plays a superfluous role. I know before taking the picture that I will convert it to black and white. Then I focus mainly on shapes, mood, and graphics.

In some other cases, I decide to convert to black and white after having taken the picture. The series “Chaos” is an example. It could work in color, but I wanted to express the effect of time passing, starting from simple shapes and moving to elaborate, fractal patterns, when the distinction between past and future is not relevant. I felt that using different shades of gray was an interesting way to illustrate this effect.

How many days do you usually spend in a new place to adjust and photograph in greater depth?

It depends on the size of the place, of course. Usually, I stay between two to five days. I don’t know why, but I usually have a great deal of difficulty taking pictures on the first day. I need to immerse myself in the environment. Staying several days also allows for different light conditions.

What type of response do you hope to elicit from your audience?

I really don’t know. However, I appreciate it when people are “stuck” in front of a photo, when I sense their confusion because classical visual cues don’t apply anymore. It recently happened to me at an exhibition on the “Magma” series held at the Salon des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Many people were really disoriented but attracted by the series at the same time. They asked me, “Is it painting?” and “What is being represented?” I enjoy this type of response because it leads to a discussion about the photo.

Do you think about the audience when you photograph?

I never think about the audience. I don’t need photography to make a living. I am free from commercial pressures. In addition, unlike many photographers, I don’t lead workshops, so I don’t need to focus on creating pictures that a workshop participant expects to see.

This freedom is priceless. I feel free to take any pictures, to try any techniques without asking “will that picture appeal to potential buyers and magazines?” Having such constraints would significantly hamper my creativity.

You spoke of making your work evolve as one of the most important challenges. Is that still your main challenge?

Yes, it remains my main challenge. It doesn’t mean that all the photos I take and publish reflect the evolution of my work. I often publish images made with a similar technique or with similar considerations.

However, I feel a kind of dissatisfaction. It pushes me to recall what I have previously done and try something different. Then I experiment with different ways of seeing and new techniques. I try again and again until I achieve what I consider a visual breakthrough.

I’ve been feeling a little stuck in my photography. I fear that I am doing more of the same images and not growing as a photographer. Some photographers advised me to try photographing other landscapes (e.g., deserts) and other subjects (e.g., architecture, night in cities), or try projecting other types of aesthetics (e.g., something more turbulent). Could I get some advice from you too?

I agree with the advice, but I would add the following. I think there are two ways to evolve and mature. The first consists of going deeper and improving our techniques and our way of photographing. The second one involves exploring and diversifying. Doing just the first would limit ourselves to the “already seen” and probably weary the eye. Pursuing only the second may lead to superficial work. The right balance is subtle, complex, and personal.

Thank you to Xuan-Hui Ng

Follow on instagram: @xuanhui_ng

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Juliette Ludeker: Somewhere You Can Never GoFebruary 16th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Carolyn Monastra: Divergence of BirdsFebruary 2nd, 2026