Focus on Aging: Carole Mills Noronha: That Place He Goes

By Beate Sass and Ruth Steinberg

When we invited artists to respond to our call for projects about aging, little did we anticipate that every photographer who submitted would be highlighting their parent’s story. This should not have come as a surprise. Statistically, we are living longer than previous generations, however, our social and health services have not caught up to this reality. The impact of this omission is that the care for our elders has fallen increasingly to their children to oversee or manage hands-on themselves. Although our experiences in photographing our loved ones are varied, one commonality we shared is that we became caregivers, to various degrees, to one or more parents. We also recognized that as the end of life neared, the time spent with our parents was even more precious, and yes, at times challenging and frustrating as we navigated a world of elder care that is tragically under-resourced.

People are living longer and healthier lives, yet elders often experience physiological changes in vision, hearing, mobility, and cognition which can lead to a loss or reduction in capacity. How we define capacity can be more generous than just considering the losses. Assistive devices, such as hearing aids and walkers, specialized senior programs, and hiring direct support professionals, enhance capacity and the enjoyment of life. We’ve witnessed many of our parents adapt to quieter pleasures and simpler joys, which gives those of us who support them an important lesson on how aging can still offer delight, no matter what stage of life one is in.

As photographers, we can show aging in all its expressions: there is no “one size fits all.” This series of five projects honors our parents, those still with us, and those who have passed. We celebrate how they lived, and how they continue to embrace life, despite their losses and challenges.

Carole Mills Noronha lives in Melbourne, Australia. A mother of two, a photographer, a carer, and an educator.

Carole aims to document and create honest, tender, raw, and intimate photographs from a place of love, respect, and the need to tell another’s story.

Carole has been exhibited in Australia and internationally. Her work has been recognized by LensCulture, International Photography Awards, and the Julia Margaret Cameron Awards.

Instagram: @carolemillsnoronha

That Place He Goes

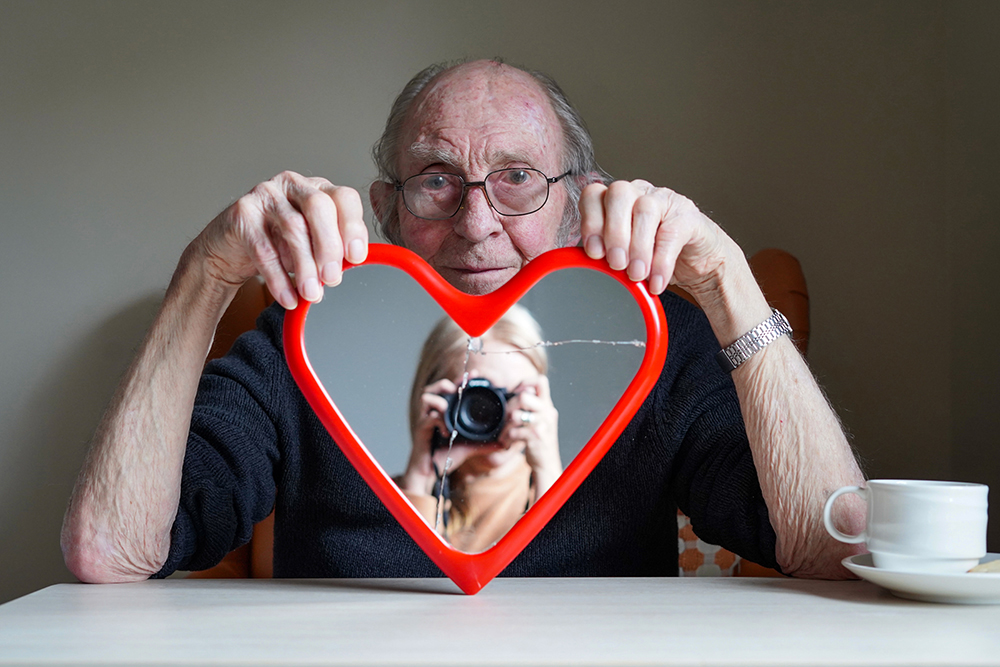

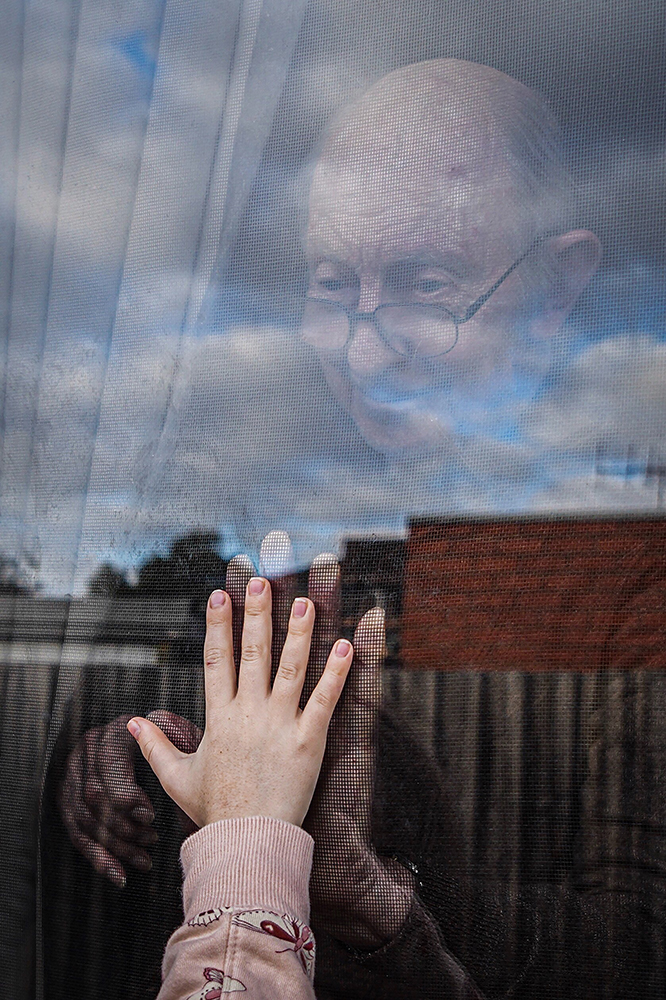

That Place He Goes is what I consider to be my life’s work as a documentary photographer, capturing everyday moments of my dad’s days as vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s erased them. Not only are these images incredibly special to me, but they also became visual proof for Dad of what he had experienced the day, week, or month before. The photographs became our thing, our tradition. They often opened memories in Dad’s mind, of places he’d been, windows in his mind. The stories he told were as far-fetched as they were true. My photos found him smiling, reliving his childhood with absolute clarity as if he was still that child, and gave him visual evidence of his pain when he had broken ribs or needed to put a name to troubling thoughts of someone he couldn’t quite place. My photographs became anchors to the present day as Dad faded further and further to the place dementia took him. My series focuses mainly on the last four years of my dad’s life. He spent his last three years in an aged care home receiving full-time care. My images explore the complexities of not only living with the daily challenges of dementia and Alzheimer’s but also the added difficulties of isolation, separation, and loneliness that the Coronavirus pandemic lockdowns caused. I promised Dad during the dark times when he sat alone in his room month after month in restricted isolation that I would share his story with the world through my photography.

I aimed to always photograph Dad with dignity, respect, and love. Dad was a quiet and reserved man. I always relied on my gut when photographing Dad, wanting to tell Dad’s story without upsetting him. After all, it was his story and it needed to reflect Dad’s morals and values. As his daughter, all I can hope is that I have told his story well. I hope the photographs are filled with the enormous love I have for him.

Interview by Beate Sass and Ruth Steinberg

Did you have any artistic influences or inspirations growing up that shaped the way you see your world?

Having childhood epilepsy shaped my world. My childhood was a constant study and crash course in light. I suffered from photosensitive seizures triggered by any sudden change in light. To avoid seizures as much as possible, I became hypervigilant to my surroundings. I became a keen observer fully aware I wasn’t like those around me. Light determined what I could do and when. My health depended on it. Ironically, being photosensitive trained my eye on what photography is all about, light.

How did your mum’s death in 2013 influence your decision to establish a photography practice and begin photographing your father?

Mum’s death was a shock. Sudden. No time to say goodbye. It completely floored me. All that remained were her things and memories. I wish I had more of her. More photos, more time. Six months after losing mum I travelled to Cambodia. It was the first time I had taken photos in a long time. I saw new things. Losing someone changes everything. At least it did for me. I began photographing our family home and more of Dad. As his health started to decline it was something I felt compelled to do. Photographing Dad was a gift to both of us. The more photos I had, the more of Dad I had.

Your father appears as a willing participant in your pictures. How did he react to being photographed and was he always aware of what you were doing?

Without fail, I always had my camera with me when visiting Dad. I didn’t photograph him every time. Only if I saw a moment or had an idea that Dad was happy to participate in. Dad was familiar with the camera. Years ago, when I was at art school, Dad would sit for my photographic assignments. Even when Dad’s dementia progressed and I told him of an idea I had to photograph him, he’d answer with, “Righto, where do you want me?”. It was our thing. He was aware of the camera but as he was rarely living in the present, he’d be surprised to see the photos on my next visit.

What is the relationship between the young child that appears in several of the photographs and how did she respond to your father’s decline?

The young girl in the photos is my niece. Dad called her “Junior” as he couldn’t recall her name. Junior grew up living with Dad from birth. They were very close. She was born a year after Mum’s death and her presence made Dad smile again after losing his wife of 49 years. Dad was her only remaining grandparent. She was incredibly patient with her grandpa, and she took his decline in her stride. Her matter-of-fact nature served her well and she spoke beautifully at his funeral. There was a knowing between them. A connection. She managed her grandpa’s decline better than I ever did.

In your artist statement, you talk about how sharing the photographs with your father became a way of connecting with him and jogging his memory, regardless of whether his memories or stories were true. Was it your intention from the beginning to share these portraits of your dad with him, to elicit memories and conversation?

Yes, I always shared my photos with Dad. As his dementia and Alzheimer’s progressed, my photos became increasingly important and valuable as they were proof of Dad’s life. A life he had experienced yet had no memory of. The photos told Dad that he’d had broken all his ribs and had spent a month in hospital. That the giant foil balloons in his room were because we had celebrated his birthday. The photos were like pieces of a jigsaw giving answers for lost memories. This was especially important after weeks and months of lockdown isolation where we couldn’t visit. Dad’s speech declined during these lockdowns. The visual cues of the photos were simply a way of initiating conversations again and improving his communication.

Your love and respect for your father is evident in all your photographs. You said you always “relied on your gut” when photographing him. Were there things you thought about or unspoken rules you created for yourself that you honored as you photographed him?

Absolutely. Dementia is all about losing oneself. Dad was extremely vulnerable and confused a lot of the time. He trusted in others. He trusted in me. There were parts of his care that left him totally raw, and it was up to me to protect his dignity. I never photographed these moments. Dad was a proud and private man, and I knew where to draw the line. Dad’s care and well-being were my priority. I never wanted my photographs to be a source of confusion or upset for Dad.

Emotionally, how did you cope as you photographed your father fading further into his world?

I don’t think I really coped. I just knew I needed to be with Dad as much as possible, especially during all his hospital visits, as he experienced the pain and the delirium. Dementia is so cruel and ever-changing. The more he faded the more it felt like I was keeping parts of him one photograph at a time. Part of getting by was accepting that Dad’s reality wasn’t always the same as mine. Physically he was in an aged care home, but in his world, he’d be at work or visiting his uncle. I entered these worlds with Dad for they were his reality. Dad was always my dad. He just had dementia. Sharing my photographs connected me with others going through the same emotions and loss. This gave me strength knowing Dad and I were being seen. We weren’t the only ones.

Beate Sass is a photo-based artist whose imagery is inspired by the Southwest region where she grew up and her experience as a mother and advocate of a daughter with a disability. Beate is not only drawn to capture the essence and beauty of her subjects but to also utilize her knowledge of visual storytelling to highlight and amplify the voices of those who are often overlooked. Most recently, Beate has turned her camera to the natural world and seeks to capture the peace and beauty found in wild places.

Beate’s photography has been featured in solo and joint exhibitions including The Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia and the Southeast Museum of Photography. Her projects have been published in Lenswork, Oxford America, and South x Southeast Photomagazine. She has also self-published two zines and created a large-scale installation that was displayed in her hometown of Decatur, Georgia.

Instagram: @beatesassphoto

Ruth Steinberg is a photo-based artist who uses the camera as a tool to open doors to conversation, uplifting the voices of her subjects. Through visual storytelling she examines facets of dignity, resilience, and presence, with particular focus on the elderly. Her work has been shown across North America and internationally including the Karsh-Masson Gallery in Ottawa, LACP: Centre of Photography in California, PhotoPlace Gallery in Vermont, and FotoNostrum, Mediterranean House of Photography in Barcelona. In 2017, as part of an intergenerational chain of mentorship, Steinberg was selected to exhibit in Continuum: Karsh Award artists welcome a new generation. In 2022 she received the first place for the Figureworks Exhibition and in 2023 she was a Photolucida Critical Mass 200 finalist.

Instagram: @ruth_steinberg_photographs

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026