Interview with Kaitlin Santoro: Memory and Photographic Ephemera

“My work explores time, memory, and impermanence. I am interested in who gets remembered, how we are remembered, how memory changes, and why certain things are forgotten. With a family history of dementia, I seek to understand the brain’s lucidity, memory triggers, how much a person’s memory can be removed before they are changed, and the endurance it takes to try to hang onto one’s mind when dealing with a cognitive disease. I try to show the personal experience of losing one’s memory and doubting one’s mind.”

– Kaitlin Santoro, Artist Statment

To start things off, can you talk a little bit about how you transitioned from working in a more traditional print format to now using glass and various other forms?

Well, I started with traditional photo printing, and have been obsessed with using a camera ever since I was little. It started with shooting using my family’s film camera and occasionally disposable ones, but then I took darkroom classes and started shooting digitally in high school. Going into college though, I started taking printmaking, and I got really interested in how you can combine the two.

It opens things up and allows you to get a different kind of texture. Even in the darkroom though, and even back in high school, I had been cutting up negatives, piecing them back together, and just distorting them in any way I could, there was always this fracturing… I didn’t fully understand it at the time, but there are all these different layers of destruction and care. The process of destroying something and repairing it is really special, especially with knowing what was lost. Which of course I didn’t consciously get at 18 *laughs*.

So, I continued doing photo printmaking hybrids, screen printing, photo etchings, different types of photo litho, all that sort of stuff. But then when I got to grad school, I took my first glass course, and I took it as an elective. I thought, “Oh it’ll be fun to blow some cups, make some bowls” but then I was opened up to all that glass can do.

I mean photography and glass have such a long history. Glass has been such a necessary material for the process, and I fell in love with it. It’s a complicated material, like it protects you but can also hurt you, it’s strong but also super fragile, it was as fluid at one point and now it’s solid… it’s weird! It just does not make sense!

But I really liked it in terms of how it hangs onto memory, very much like how we hang on to memory. Like even if there’s a teeny tiny crack that starts out small, over time, with added turbulence or trauma, it slowly grows. I feel like that’s a really good metaphor for how we are as people. Even if you don’t see the trauma, it’s there, and it affects the strength of the material. Eventually, with enough pressure, time, or damage, it can just break.

Despite that, you can fix it though. Usually through a very traumatic way, firing it and putting it in a kiln, but you can repair it. Just like with people, the cracks might still be there, and they become part of you, but you can fix or heal them to a point.

And yeah, there are just so many different image processes you can do with glass. Also, it’s transparent nature, and how it casts shadows. Shadows represent so much, there’s this absence and presence about them. Like there has to be a presence there, but it’s not actually the “thing,” not actually the person or the memory.

Building off that, can you talk a little bit about ephemera and memory? In terms of how you approach material choice as a way of connecting the two.

Yeah, ephemera and impermanence are a huge part of it.

Even thinking back to my BFA show, I intentionally chose a process that, whenever I would print, it would break down more and more. I was very obsessed with how I couldn’t edition it because the plate would break down and I kinda liked them being one-offs. It mimics the way we remember.

Like if we have an event and then the event passes, every time we think about that event, it shifts. We don’t actually remember the event itself after the first time. We remember remembering it. So every time, it breaks down more and more. I definitely like referencing that sort of process in my work.

Also, when I was studying at Tyler School of Art, I did a series that was three body prints on acrylic. Since it was at the height of COVID lockdown, I couldn’t hire models and I wanted to do things as safely as possible, so I was using myself. When you’re making the body prints you have to be totally engaged with yourself and your surroundings. Being really meticulous about where pressure is applied, and by what body parts. The subtle movements make a big difference, and it’s especially important when considering your motions when lying down and getting up.

It ended up turning into an exhibition and these 3 plexi panels. They’re done with just oil and then flocked, so they’re kind of dusted with a powder mixture. The mixture looked like ash, and water was used too, which dropped down over the panels collecting into trays. Every day I filled these basins with ice, and as the ice melted, the drips would hit the panels and slowly erode the figures.

It was all about impermanence and ephemera focused on who we are, but then by collecting the remains, it created drawings in the trays. So it ended up being like “So we’re here now, but what are the traces we leave behind?”

When it comes to using found images, how do you go about pairing them and using them in conversation with images you make?

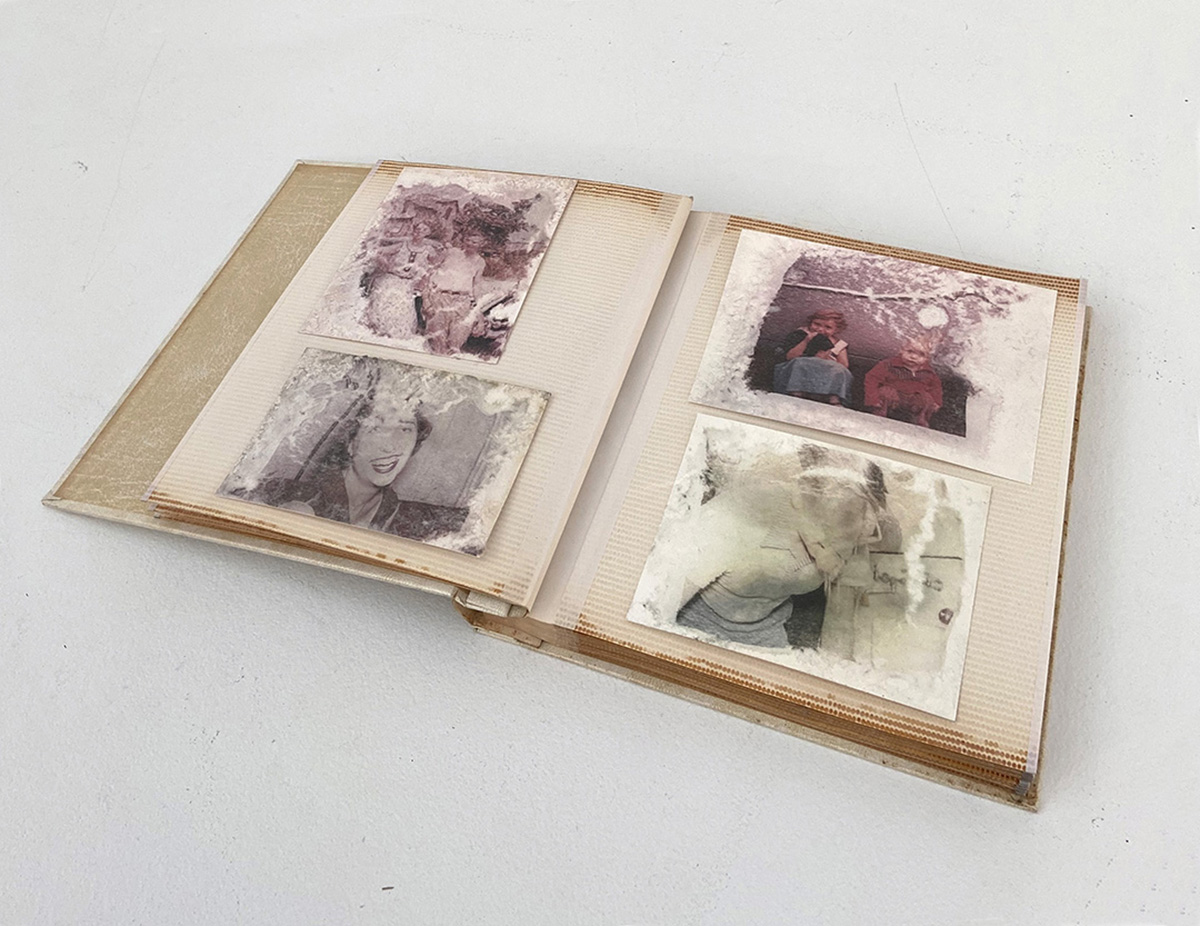

I mean, I use a lot of family archives, and my grandfather was typically the one taking the photos in my dad’s immediate family. I’m really interested in being able to see the world through his eyes, alongside just the general aesthetic of family photos. They’re made purely for the point of remembering, and there’s that amateur aesthetic too. Not really overthinking any formal qualities of the image, but just having the desire to capture something for the sake of remembering.

How does your process for developing work evolve in terms of a research basis? For instance, where some may artists be influenced by literature, music, or visual mediums, for you is it delving into family history, and are there other topics you’re investigating as well?

I read a lot of neuroscience… I love it and can’t get enough.

I also watch documentaries on the brain, it’s fascinating to me. By no means Ph.D. level stuff, but I think learning how the brain works is a big part of my practice.

I’d say the other half is material studies with fugitive materials. So materials that will shift and change depending on the environment they’re in. Whether it’s printing on glass or acrylic with something that will wash away, or sugars that will dissolve… I tend to use a lot of materials that dissolve in water. I like using water as a catalyst, it’s natural and nothing can exist without it, alongside it being a good indicator of time.

So yeah, just playing around with lots of different materials. I like to learn processes and then intentionally try to push them to their breaking point.

In terms of the progression of your work, I feel like your newer work is beginning to explore lineage and memory in relation to place rather than people. Can you talk about the transition and how it’s developed?

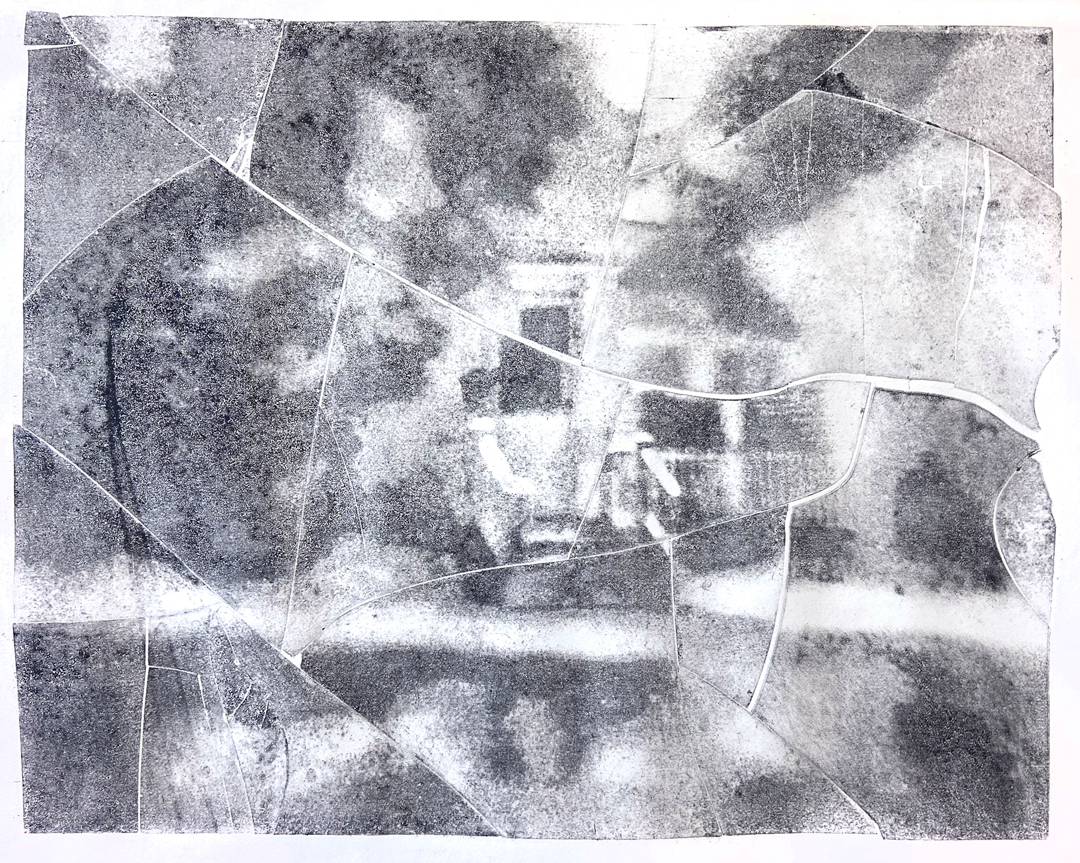

I think moving further away from where I grew up and my family definitely influenced that. But I think a lot of the work involving place has to do with the search for something familiar in an unfamiliar place… almost searching for a place that could be home.

And then with your choice of printing them on glass, they kind of look like buried memories. Are you choosing that material and printing method as a conceptual gesture to how inaccessible some memories can be?

Yeah, exactly! I’m focusing on that haziness of a memory or being in a new place. Most of the places I documented in this body of work I only lived in for a brief amount of time, usually only a handful of months. So, I don’t think I fully ever connected with them and saw them as a home, and despite trying, I knew they were never going to be. In those types of places, you’re only there for a fleeting moment, but it’s hard to not be searching for a sense of home.

The work feels like a documentation of my life, investigating my relationship with my surroundings.

What’s the process like for creating this body of work in particular?

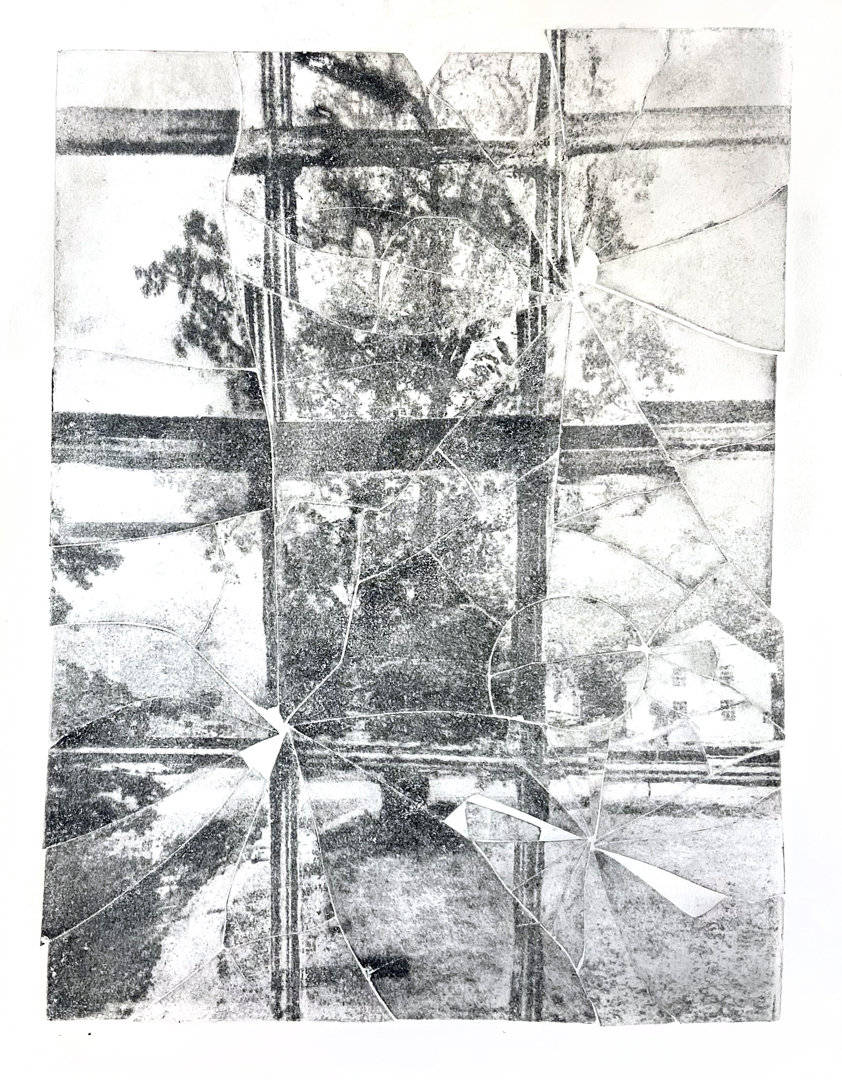

Well, a lot of the images were photographed with a Lensbaby. Which creates a really shallow very selective focus, and so there’s distortion present in the original image.

But then I take those images and I laser etch them onto glass. I actually use those glass plates as printing plates, so I run them through an etching press. They’re glass so they break under that intense pressure, but I’m able to control… not how they break, but enough to keep them from fully shattering. Then I make prints with them until I can’t anymore and I’m satisfied with the form, usually listening to the glass and not forcing it.

It once again comes back to that process of remembering and the breakdown that happens in that process. So, I feel like inking a glass plate, printing it, it breaking, collecting the pieces, inking it again, trying to print it again, inherently mimics that. It’s all about distortion.

Even in the installation process, I focus on that. I use really dramatic lighting which casts these shadows that distort them even more. Playing into that idea of having a memory, but not quite being able to see the memory, and the interplay of the two.

I’m also spending some time thinking about how the more traditional prints and glass speak to each other. As well as experimenting with them co-existing, right now they feel like two different bodies of work.

In that same vein, what are the next steps you’re taking to push your work further? Whether it be a conceptual investigation or something in relation to material.

Right now I’m just beginning to experiment with screen printing using photochromic and thermochromic inks. So inks that will react either to heat or light. With heat you’d have to touch them to activate them, then with light, depending on the room, it’s an image that will either reappear or disappear. I’m really interested in creating interactive pieces in that way.

I also really want to make a book. Which would be more of a return to 2D work, but still in an experimental way. Whether through those inks, maybe different paper types, or layering… I’m not sure yet, but I love the intimacy the form presents. I’ve been collecting a lot of images and writings from over the past decades, and I really want to start connecting the threads.

Kaitlin Santoro is an interdisciplinary artist who works across photography, glass, and printmaking to explore impermanence, loss, and memory. She creates work that slowly breaks down and shifts to illustrate the fragility of memory over time. Santoro pushes the traditional boundaries of lens based, print, and 3D techniques by using incompatible materials, creating and using distortion lenses, or working in non-archival methods.

Santoro’s work has been exhibited internationally, including shows at the International Center of Photography, UrbanGlass, and the Print Center of New York. She has been awarded residencies at the Manhattan Graphics Center, Pilchuck Glass School, DaVinci Art Alliance, the Sculpture Space, and the Oxbow School of Art. Santoro has presented at the Glass Art Society annual conference, Pilchuck Glass School, the Tyler School of Art, and Queens College. She received her BFA in Photography from the University of Connecticut and her MFA in Photography from the Tyler School of Art and Architecture.

Follow Kaitlin:

Jake Benzinger (he/him) is a photographer and book artist based in Rockland, Maine; he received his BFA in photography from Lesley University, College of Art and Design in Cambridge, MA. His work explores the intersection of dreamscape and reality. Through the dislocation of space, he weaves together imagery to construct a world that exists in the liminal, investigating themes of duality, longing, identity, and the natural world.

His work was recently featured by Fraction Magazine, and has been exhibited both nationally and internationally. Jake’s body of work, Like Dust Settling in a Dim-Lit Room (Or Starless Forest), was recently self-published, shortlisted for the 2023 Lucie Photo Book Prize, and sold out of its first edition of hardcover books. A second edition was released in late 2023, coinciding with a solo show at the Griffin Museum of Photography.

Jake is currently a gallery assistant and workshop coordinator, a content editor for Lenscratch, and the founder/lead designer at wych elm press.

Follow Jake:

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Chelsea Tan: before the light escapes us…July 7th, 2024

-

Josh Raftery: Start the Story at the EndJune 28th, 2024

-

THE CENTER AWARDS: ME&EVE GRANT: ANNA REEDMay 22nd, 2024

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Earth Month: Photographers on Photographers, Dennis DeHart in conversation with Laura PlagemanApril 16th, 2024