Charles Ingham: 100 Invocations: Gods, Saints, and Fellow Travelers

One of the best parts of jurying an exhibition is discovering a treasure trove of amazing work. I recently had the great pleasure of selecting work for the Center of Fine Art Photography‘s exhibition, Words and Pictures. It was there that I discovered the work of Charles Ingham. Ingham submitted so many stellar works to the exhibition, that it was hard to select an image or two to include. His work deftly combines photographs, old and new, text, ephemera, and graphic elements into small novellas of visual storytelling.

An interview with artist follows.

Charles Ingham is a conceptual photographer living and working in San Diego. Born in England, he received his undergraduate and graduate degrees from the University of Essex before moving to California in 1982 to teach in higher education. He is a studio artist at ArtHatch in Escondido and a member of the Snow Creek Photography Collective.

100 Invocations: Gods, Saints, and Fellow Travelers

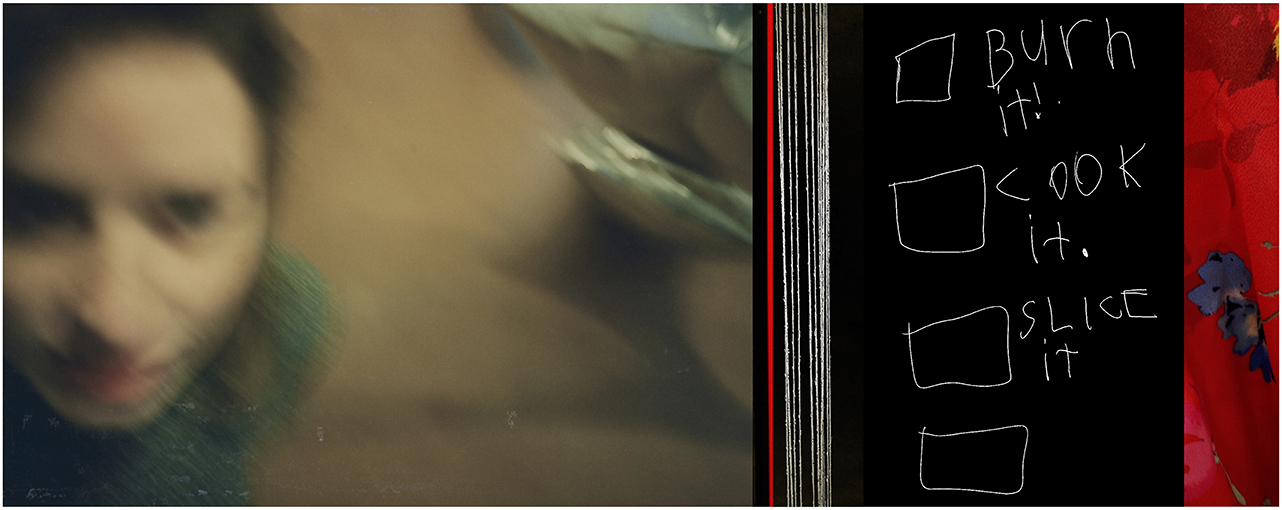

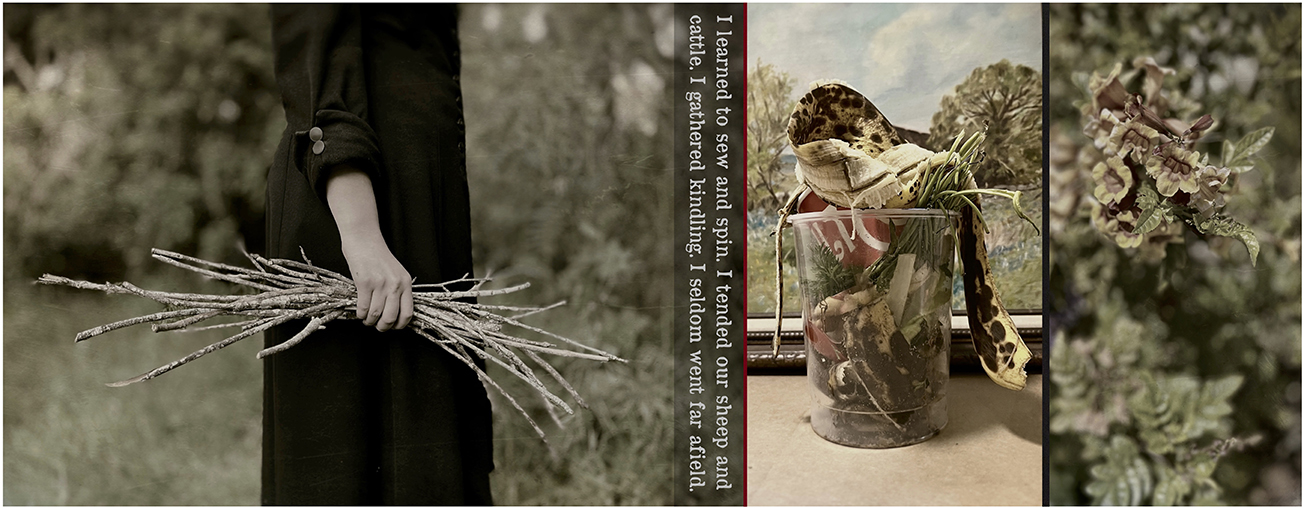

As a conceptual artist, I create photo-narratives that are hybrid forms, transgressing distinctions between the verbal and the visual. My art represents a combinatory aesthetic; each work constitutes a whole made up of parts, creating something of a symbiosis: the words, the images (abstract and referential), the space between images, the subjects, the reference to specific individuals, places, events, or times. Many visual references are obvious; some of the bones, sinews, and other connective tissue that hold a particular narrative together work within the piece’s own logic, a logic that viewers find for themselves. Here, the artist makes the work, and that work has an agenda, but a significant part of that agenda is for the viewer to find something of (or for) themselves within these images and words. With the aspect ratio of each finished work, I wish to suggest something of a cinematic form; I like the idea of the viewers’ eyes moving initially left to right, reading the visual-verbal narrative. The thin, vertical color strips are cropped details from photographs that I have taken and serve as a form of punctuation within the narrative. The visual texts in these narratives are comprised of my own images but can also include a manipulated found image from my collection.

The images here are from a recent series entitled 100 Invocations: Gods, Saints, and Fellow Travelers, exploring figures and events from various belief systems, mythologies, and folktales.

©Charles Ingram, The Child Joan Works at Common Tasks 2024 6½” x 16¾”, framed to 12” x 20” Text adapted from Joan of Arc: In Her Own Words (trans. Willard Trask).

©Charles Ingham, After the Long March 2024 6½” x 16¾”, framed to 12” x 20” The Long March (1934-1935) represented the tactical retreat of the Chinese Red Army. Of the 65,000 members of the First Army who began the march, fewer than 8,000 survived.

Tell us about growing up and what brought you to photography.

I was nine when my parents gave me my first camera, a Kodak Brownie 127, and let me loose. In fact, I wasn’t quite let loose as my father gave me a single instruction, that one should never include people in one’s photographs (as they would get in the way of what I was trying to shoot). It’s interesting how one must unlearn so much when one is truly let loose; however, a couple of years ago I bought the identical, British-made model of the 127 on eBay and, opening its canvas carrying case, the thing still smelled of photography.

Your practice is so varied, what draws you to your specific way of working.

Every morning, I find that the poet Ezra Pound has written “Make it new!” in lipstick on my bathroom mirror. I do my level best. While the British photographer Madame Yevonde’s demand to “be original or die” is perhaps a little extreme, there is no question that making art is an existential act. Making something that wasn’t in the world before is powerful medicine. Writing on my mirror, Pound uses Rouge Dior, Edith Piaf’s trademark shade of lipstick. You can’t beat that.

©Charles Ingham, In Order to Appease a Household Deity 2023 6½” x 16”, framed to 12” x 20” The text is drawn from a Santería ritual.

When did you begin to use text in your artwork?

To be honest, I’m not exactly sure. As an undergraduate, I fell in love with the work of William Carlos Williams, not least Williams’s sense of the architecture of the poem and his exploration of the physical relationship between the word and the page, the blank canvas on which it sits. And I’ve always been drawn to the transgressive nature of straddling two “distinct” disciplines: literature and the visual arts, verbal and visual texts. I do recall that sometime in the 1970s, inspired by Duchamp’s 1919 readymade L.H.O.O.Q. and its found object (a postcard of the Mona Lisa), I created an assemblage in which I stole Duchamp’s coded naughty text and converted it to L.G.T.T.H. (“Let’s Go To The Hop”), itself stolen from the title of a Ted Berrigan poem in which he steals lines from a number of collaborators, including myself.

My graduate dissertation was entitled “Words in Pictures” in which I looked at the work of three visual artists who included verbal texts on the picture plane of their artwork.

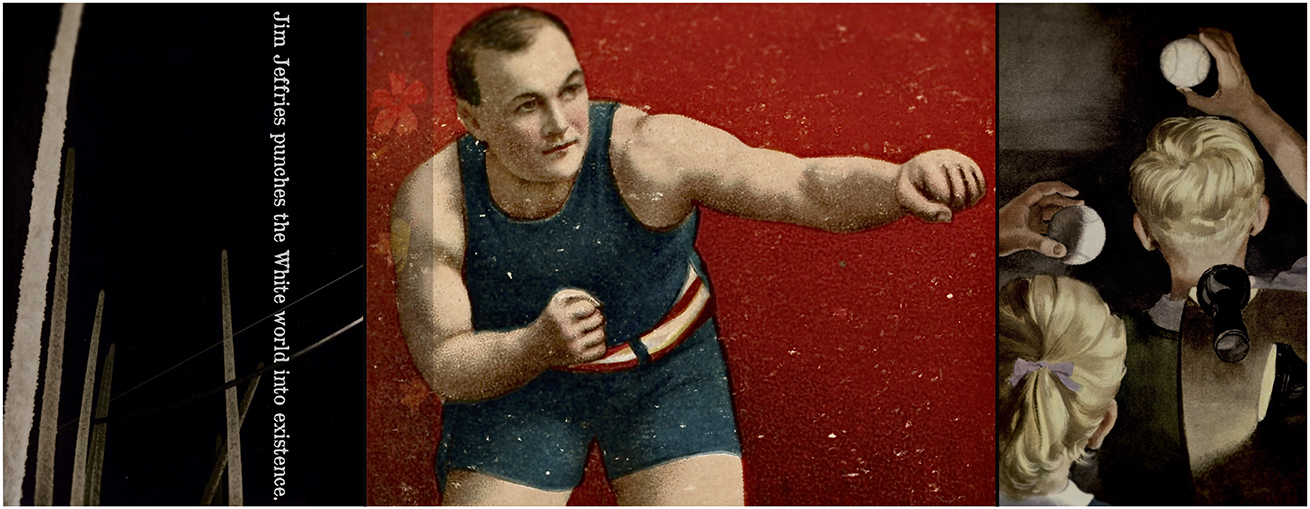

©Charles Ingham, Sucker Punch [aka White World] 2024 6½” x 167/8”, framed to 12” x 20” James J. Jeffries (1875-1953) was dubbed “The Great White Hope,” reflecting the desire that a White boxer wrest the heavyweight crown from the African American Jack Johnson.

©Charles Ingahm, The Children’s Crusade of 1212: With Nicolas 2024 6½” x 15¾”, framed to 12” x 20” Text adapted from Marcel Schwob’s The Children’s Crusade (1896), trans. Kit Schluter.

You are an incredible visual storyteller, so you write short stories as well?

Yes, publishing in some literary magazines. A sabbatical leave in 2014 allowed me to spend a month in New York, working on a project focusing on the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911, in which 146 garment workers died, most of them recent Italian and Jewish immigrant women and girls. I walked the path that many of these women took on the day of their deaths, from tenement to factory, and I gained permission to stand at the ninth-floor window from which many of them jumped to avoid the flames. The project produced a series of photographs, each matched with a piece of short fiction (the photographs not necessarily serving as illustrations of the writing). This is the project that for some years I have intended to make into a book; this continues to be “my next project,” but other ideas keep getting in the way.

More recently, in my 2019 series Sisters, I employed photo-narratives aligned with substantial pieces of short fiction.

©Charles Ingahm, Possessed 2023 6½” x 17¼”, framed to 12” x 20” A feminist reading of Shakespeare’s Ophelia.

What keeps you creatively engaged?

That lipstick text on the mirror. I can’t escape it. I don’t want to.

©Charles Ingham, Sexuality as Performative Magic 2023 6½” x 16½”, framed to 12” x 20” A cemetery in Tijuana; a municipal building in San Diego.

Who or what is inspiring you lately?

I have just finished Audrey Flack’s recently published memoir With Darkness Came Stars. I was out of the country for a month, and I’ve just discovered that Flack died on June 28, at the age of 93. Damn. Audrey Flack is probably known most for her Photorealist painting, but she is a lapsed Abstract Expressionist, and a good deal of the memoir addresses the difficulties of being a woman in a patriarchal art world (from the 1950s on). One hopes that everybody is aware of the often violent misogyny of the male Abstract Expressionists, but Flack comes out swinging, naming names (and it’s a long list).

Now I’m reading Tristram Hunt’s 2009 biography Marx’s General: The Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels. Engels lived and worked for many years in Manchester, my hometown, and I had a self-interested reason for reading the book: I’m working on a piece about Mary Burns, Engels’s partner, and her sister, Lizzie. It was the Manchester-Irish Mary Burns who showed the German Engels the “human horror” that was the city after the Industrial Revolution.

In July I was at London’s Tate Modern to see an exhibition of the work of South African photographer Zanele Muholi: humbling, moving, massively impressive, massively inspirational.

And I’m talking about photographers, artists, and writers who have inspired me lately but also unceasingly continue to inspire me. Here I’m including painters (and other visual artists) because, for me, photography and painting so often work together seamlessly.

Sally Mann, Sally Mann, Sally Mann

Gerhard Richter (not the abstracts)

Berenice Abbot

Henry Taylor

Kara Walker

Kerry James Marshall (Oh my!)

Julia Margaret Cameron

Francisco de Goya

Jean-Michel Basquiat (Of course.)

Cindy Sherman

James Barnor

Bill Jacobson

Robert Rauschenberg

William Kentridge

Nan Goldin

Frank Romero

Max Beckmann

Weegee

There are more.

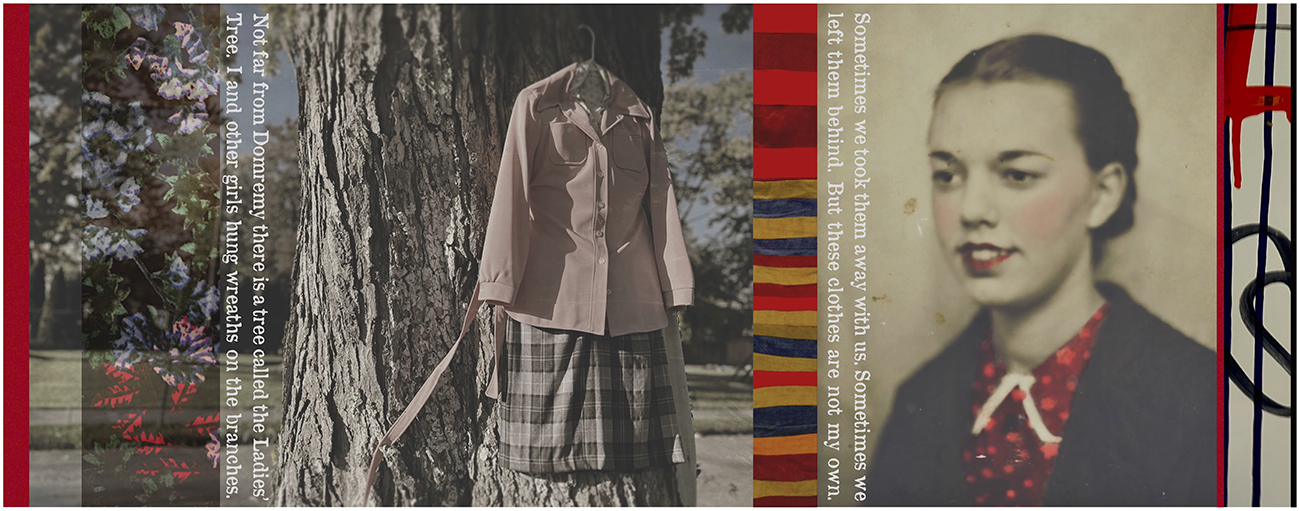

©Charles Ingham, Saint Joan 2023 6½” x 16¾”, framed to 12” x 20” Joan’s own words, adapted from Joan of Arc: In Her Own Words (trans. Willard Trask). Photograph of tree clothes taken by the artist at Tyree Guyton’s Heidelberg Project, Detroit.

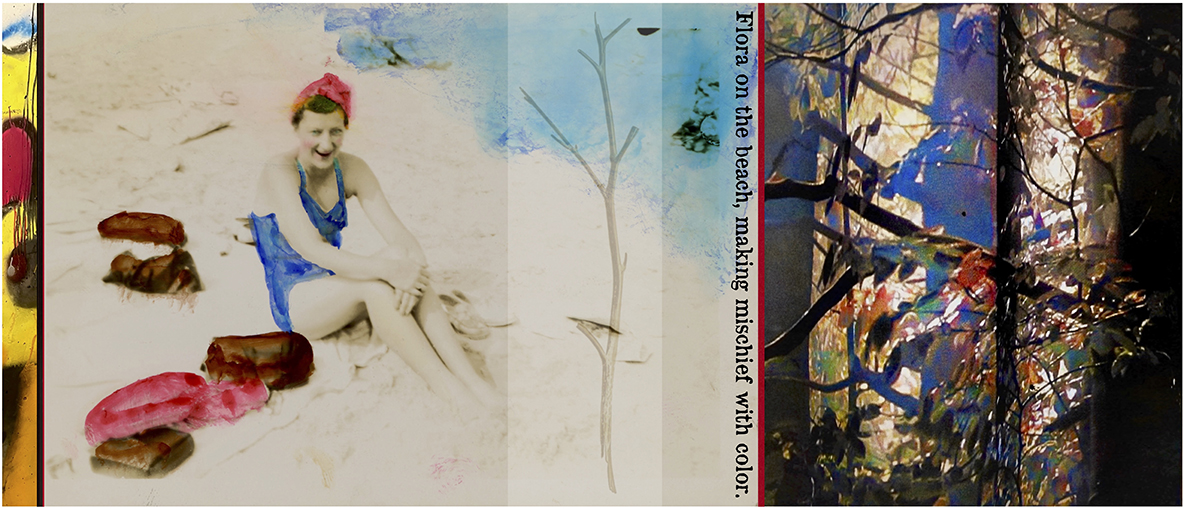

©Charles Ingham, Nymphs and Shepherds Come Away, For This Is Flora’s Holiday 2024 6½” x 15¼”, framed to 12” x 20” The title is taken from a song by the 17th century English composer Henry Purcell.

What’s next for you?

Beside me on my desk is a case of 3×5 cards on which I have written notes and drawn designs for a project that, if successful, in many ways will be entirely new for me. It’s an experiment, and it represents a challenge to make it really new.

Meanwhile, I am matting and framing works from my most recent series 100 Invocations: Gods, Saints, and Fellow Travelers. This is work that I will be showing in a four-person exhibition in San Diego, opening in late October.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025