Photographers on Photographers: Jessica Hays in Conversation with Victoria Sambunaris

I have long admired Victoria Sambunaris’s work, and felt she might be a kindred spirit in her long traverses of the American landscape. Her work tackles the difficult task of explaining the vastness and uniqueness of the American west, in its complicated mix of beauty, exploitation, preservation, respect, and challenge. Our conversation ranged across the land, recounting stories of both of our times out west, from Alaska to Texas and everywhere in between.

Based in New York, Victoria Sambunaris structures her life around a photographic journey traversing the American landscape for several months per year. Equipped with a 5×7 inch field camera, film, a video camera and research material, she crosses the country alone tenting on top of her car. Her large-scale project-based photographs document the continuing transformation of the American landscape with specific attention given to expanding political, technological and industrial interventions.

Sambunaris received her MFA from Yale University in 1999. Her work has been widely exhibited in museums and galleries throughout the United States and abroad. She is the recipient of numerous awards including the 2021 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship, the Julius Shulman Excellence in Photography Award, the Aaron Siskind Foundation Individual Photographer’s Fellowship and the Anonymous Was a Woman Award. In 2011 a twelve-year survey of her work was exhibited at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, NY and travelled throughout the US. Her work is held in numerous collections including the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, the Lannan Foundation, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the National Gallery of Art. In 2019, Sambunaris was commissioned by the Dia Art

Foundation to photograph Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty for the 50th anniversary and Sun Tunnels by Nancy Holt. Radius Books published her monographs Taxonomy of a Landscape and soon to be released Transformation of a Landscape. She is represented by Yancey Richardson Gallery in NY.

Follow Victoria Sambunaris on Instagram: @victoriasambunaris

Jessica Hays: When was the first time you thought of yourself as a photographer? Or, what was a moment that you knew that you wanted to pursue photography as a career?

Victoria Sambunaris: There are circumstances and experiences that I reflect back on that led me to do what I do today. One of my early memories as a child is sitting in the wayback of our pink Rambler station wagon during our Sunday drives looking out at the bucolic Amish landscape in Lancaster Pennsylvania. There were manufacturing companies sprinkled around and my immigrant parents worked in those factories that existed at that time. My father had an amateur interest in photography with a Super 8 movie camera and projector and one of the first Polaroid SX70’s that led to my own interest in photography. Magazines such as Life and Time were kicking around showcasing other worlds inducing wanderlust at a young age. And the worst commercial nuclear power plant accident to date occurred 42 miles from my home at Three Mile Island when I was a child that later led me to question our use of landscape. These collective experiences and others shaped me as an adult and my pursuit in photography. It became a vehicle to explore the world and continues today driving the country and scrutinizing landscape.

JH: A defining part of your practice is your time being split between New York and these large road trips across the American West. How did that begin?

VS: My project based cross-country trips began immediately after graduate school when I taught as an adjunct and had only 3 months to make work during the summer. I had an old Crown Victoria Country Squire station wagon and would pile my camera equipment, books, and maps and drive to my destinations that were researched in advanced and at the time reflected indirectly on our insatiable consumerism. I realized early on that I would need to spend my life on the road to understand all the questions I had about our history and culture and how it is reflected in our landscapes.

© Victoria Sambunaris, Untitled, (Oil/chemical tanker, Overseas Tampa, USA) Houston Ship Channel, Texas, 2015

JH: Did you always camp?

VS: Not always. Initially, I stayed in motels, when you could find $27 rooms. Those days are over! But camping began on my Alaska trip in 2003. I had driven from New York across Canada to get to the Alcan Highway and found myself in remote areas that were undeveloped on most parts of the journey. Along the way, I met an older woman who was camping alone with her dog across Canada. I thought “Wow, if she can do it, what is my fear about camping?” I pitched my tent, kept my axe and my dog, Happy, near, and discovered that the fear was in my head. After reaching Fairbanks on that same trip someone offered me their garage to lodge in for a few days. I was feeling lost about my work until the garage owner mentioned that there was a nearby gold mine and got me a phone number to a contact there. You have to remember there were no cell phones or smart phones, I was cut off completely. I called the mine several times on a pay phone leaving messages on the answering machine. A few days later, I left Fairbanks to camp at a nearby lake and Happy wandered off to another campsite. It turned out to be the person I had been trying to contact at the mine! I showed her my box of 11×14 prints and she invited me to the mine, which was pivotal moment for my work. After that, I camped regularly, moving from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez following my interest in the pipeline and the fossil fuels industry. After that trip, camping became a way of life.

JH: Do you often stay in one place for a long time, working with one community, or are you usually looking in broader strokes at the western landscape?

VS: It varies project to project and place to place. In Alaska, as I just mentioned, I would stay at one site to work for a few days then move along day by day. When I was working on the US-Mexico border in 2009, my approach varied. Del Rio, Texas became a base after befriending a motel owner who housed workers in the oil industry, allowing me to integrate into their world and gain information. He also helped me with introductions and crossing the border. Sometimes I find a place that I can settle and integrate into the community. Other times I’m moving along depending on the project.

JH: It sounds like it really it depends even beyond the project and what the landscape asks of you, what you want to do in the area and how to best do it?

VS: Yes exactly. It can change moment to moment. My current project is on the Colorado River. I made two trips in 2023 moving along the river. On one of those trips, I settled at a campground at Lake Mead just outside of Las Vegas. It became familiar and almost homey after meeting fellow campers living off grid and who were knowledgeable about the area and the politics of the river. Having someone to discuss the work with and to learn from will keep me at a site.

JH: When you are out on the trips, do you have destinations in mind and specific images you want to make, or are you a little bit more driven by chance and seeing what you find?

VS: The work is project based and researched in advance. Once I arrive at my destination, I begin by exploring the area, talking to locals, and absorbing information about the place. Of course, chance, luck and the unexpected always factor into the work. And the ideas that I arrived with consistently adapt and change as I move along. Once I’m back in NY editing, the project starts to take shape and I’m able to better define those initial ideas. I usually return to the road to fill in what’s missing.

JH: Can you talk about your experience working in an artist residency setting at Galveston?

VS: The Galveston Artist project grant was a fantastic experience. I had scouted the Texas Gulf coast area years before and knew I wanted to return. The area intrigued me with its abundance of petrochemical plants and shipping terminals. I connected with the founder of GAR (The Galveston Artist Residency) Eric Schnell. Though I didn’t do a full one-year residency, I was invited to do a special project for one month. Through GAR, I was introduced to a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) marine biologist, Chris Benson, who educated me about the landscape and the impact of the petrochemical industry on marine life. His insights into the history and current concerns of the area enlightened me enough to do a larger project that kept me returning over the course of one year.

JH: Beyond the work you made there, did that experience impact your practice and how you go about your road trips?

VS: Residencies are a great resource for making work because they provide a stable base and the opportunity to engage with locals and make connections. It’s different from camping where there are time consuming tasks of finding a camping spot, making a fire, pulling out your equipment to cook. Being on the road is not always comfortable, and a residency can be a space of comfort and stability.

In 2022, I did the Joshua Tree Highlands Residency while working on a project in relation to California’s deserts and water issues. I stayed there for six weeks, which allowed me to drive to the Salton Sea, Imperial Valley, and Anza-Borrego Desert to work for several days at a time, then return to reload film, shower, reorganize and go back out. This balance made it easier to handle the grueling nature of being out in the field for extended periods.

JH: I also split my time between two places, primarily Chicago and Montana/the west. I’m really curious to hear about how you manage and organize your time and life around two places and your travels?

VS: As you might know, living a dual life can be disruptive. But process is a big part of the work and I thrive on the dichotomy of the two worlds I have created for myself. When on the road, I am scouting and shooting and when in New York, I am editing and printing. I shoot 5×7 film that requires as much time in the darkroom as the time I spend on the road. Both aspects of the work are slow and meditative and crucial to the work. Not to mention, the differences of living in a crowded and frenzied city verses the solitude and isolation of life on the road. I’m sure you experience those differences, as well.

JH: I think I take a similar approach, where there’s the time photographing and being out in the landscape, and the other time, where I completing the rest of the steps to actually produce the work into its final form.

VS: Absolutely, one feeds the other.

Each time I drive west, I’m still awestruck when I go back out. And I can see more of the evolving relationship we have to land in how people are interacting with it differently every year. And I’m sure you can relate to the changes in the same way, because you see it, too.

JH: Being out there experiencing it is such a big part of things, but the time back in the city gives those experiences perspective. I think I love the mountains more now, or never take them for granted now that I’m away part of the year.

VS: The back and forth helps to see it better. You don’t take it for granted because you aren’t seeing the same land daily. I see these places more clearly after the distance and the time away.

JH: I saw that you taught for several years following graduate school. What did that add to your practice? How did you make the decision to leave teaching? Were you able to immediately transition into photography full time?

VS: I taught photography in the architecture school at Yale immediately after graduate school. But the class was not “architectural photography”. I enjoyed teaching, the interaction with students and the architect’s approach to seeing the world through the medium. You learn as much from the students as they do from you. As far as my own work and teaching, I was only able to get on the road in the summers. This inhibited the work and eventually, I realized I needed more flexibility in my life to remain on the road. It was terrifying in the beginning, it is a precarious way to live not knowing when you might have income. But the architecture school was removing the darkroom and it felt like a sign that it was time for me to make a change and devote myself to the work entirely. I began to pick up editorial work to help fund the trips, credit cards, loans, whatever it would take. Later came grants and sales. I live a minimal existence and I have chosen not to live a more conventional life with a family and such. My responsibility is to myself and the work. While traveling, I’m camping, living modestly and in the moment. There is nothing comfortable in what I do but it keeps me on my toes.

JH: When I hear about your work, it is often emphasized that you travel alone on these trips. In what ways do you think that changes the work or your working methods?

VS: Traveling and working alone allows unmitigated focus. It’s work. Every day I am in pursuit of something that is undefined and any kind of distraction disrupts that process.

JH: What advice can you give to emerging photographers about maintaining and nurturing their practice?

VS: Stay true to yourself and your practice and avoid trends. Have patience with your work and the time needed to make good work. Fill your world with inspiration (art, film, literature, poetry) that feeds you and take time for contemplation and self-reflection. And most importantly, stay curious and open to the world.

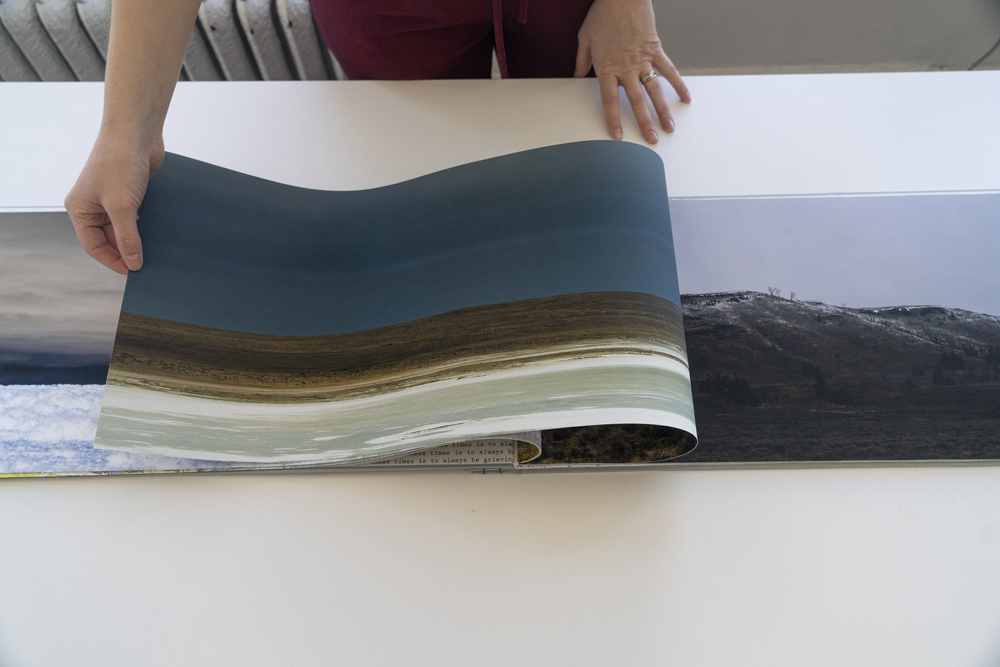

JH: Your practice seems to be, at large, making work that could be related into a single large body of work, Taxonomy of a Landscape. How do you conceptualize that work into books? What is the process of creating a narrower story for your books?

VS: I’ve done only two books in 24 years due to the time it takes for me to complete a body of work. Both books Taxonomy of a Landscape and my upcoming book Transformation of a Landscape reveal not only the work itself but the various layers of the work that touch on my process. This includes: snapshots, ephemera, books, maps, journals, road logs, and other artifacts.

They reveal a larger picture of my work and life on the road.

© Victoria Sambunaris, Untitled, (Lake Manly with photographers), Death Valley National Park, California, 2023

JH: Can you tell us more about this new book? How does it grow from Taxonomy?

VS: I see my work as one big project focused on the landscape, with each aspect connecting to the next. For example, while working along the canals that feed the Colorado River into California’s Imperial Valley, I became curious about the Colorado River itself. This curiosity led me to explore its significance in the West, the seven states that rely on it, and the low reservoir levels and depleting water that the west is faced with. This idea stayed with me and brought me back to the Colorado River, not just to photograph it, but to examine our interaction with it. Recreation has become a significant focus, as I now see many people engaging with the landscape differently from say 20 years ago. The focus I am witnessing seems to have shifted from “the landscape” to “me in the landscape”.

Jessica Hays is a photographer, artist, and bookmaker based in Montana and Chicago. Her intimate work draws on personal experience to communicate ubiquitous human experiences, tackling topics like mental health, trauma, environmental issues and loneliness. Grounded in the American west, she explores relationships between people, places, and experiences of being deeply connected to ones surroundings. Her work blurs the lines between the uniquely individual and collective experiences.

Hays works in a variety of processes including pigment printing, handmade artist books, video, and historic and experimental photo processes. She has lectured on topics of mental health and alternative process photography at conferences, mental health summits, and as a guest speaker in classrooms. Her work has been shown internationally in galleries and museums, published in a variety of magazines and textbooks, and is held in several public and private collections in the US and Canada. Hays received her MFA in Photography from Columbia College Chicago, and earned a BA in Film and Photography and a BA in Environmental Studies concurrently at Montana State University. She was recently recognized as a Chulitna Artist fellow, Critical Mass Finalist, and featured in solo exhibitions in Tennessee, Montana, and Illinois. Hays’ work aims to explore the long lasting effects of the land on human psyche from trauma to restoration. To view more of her work, please visit jessicahaysart.com

Follow Jessica Hays on Instagram: @jess_the_photographer

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Juliette Ludeker: Somewhere You Can Never GoFebruary 16th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Carolyn Monastra: Divergence of BirdsFebruary 2nd, 2026