Hannah Kozak: Survivor: My Father’s Ghosts

Hannah Kozak, photographer, film maker and writer, retraces her father’s footsteps of his stays in eight Nazi forced labor camps in Germany from 1943 until liberation on May 8, 1945 with a new series shot on film owith a 1961 Rolleiflex 2.8F, created as printed silver gelatin prints. The project, Survivor: My Father’s Ghosts, opens at the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust in Los Angeles on May 20th, 2018 at 3pm, with a film screening at 4pm. The exhibition runs through August 20th.

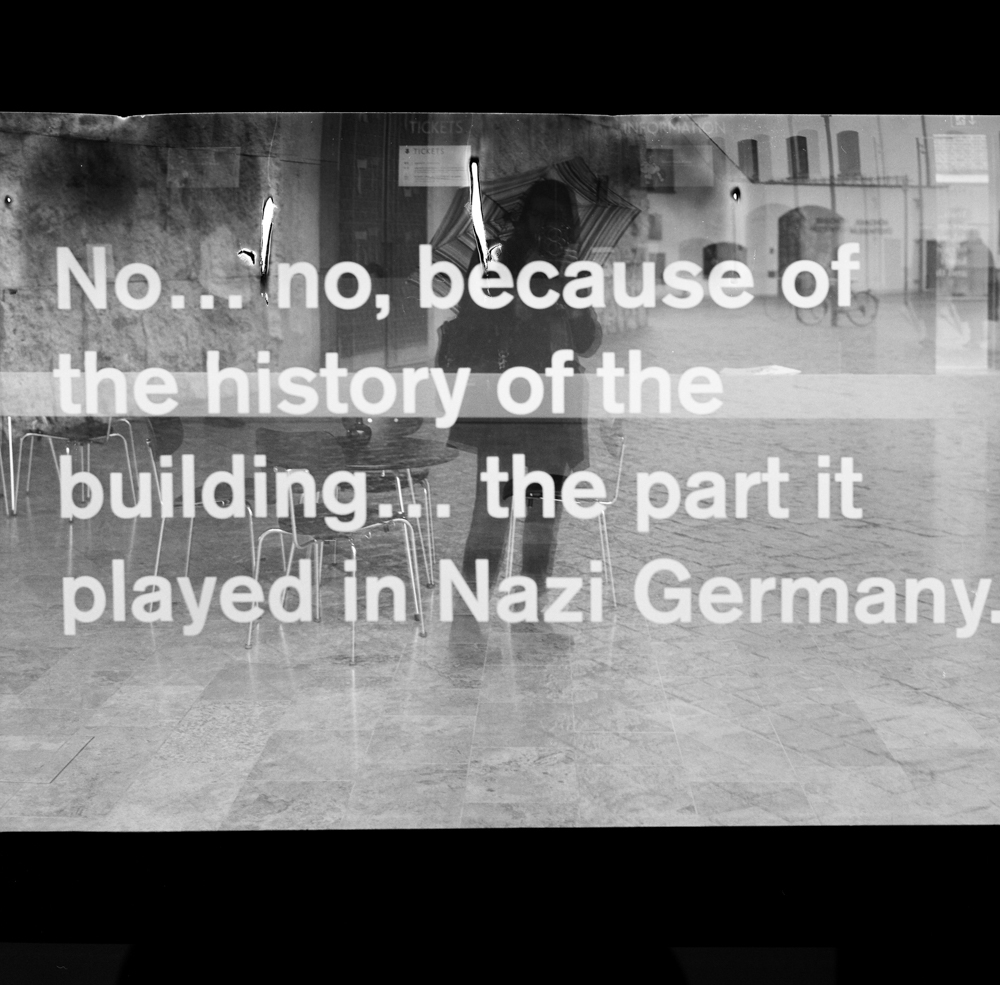

From 2013 to 2017, on multiple sojourns, Hannah traveled to Poland to see and photograph Auschwitz-Birkenau, Markstadt, Klettendorf, Dernau, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Majdanek, Chelmno, Gross Rosen, Hirschberg, Erdmansdorf and Bad Warmbrunn. She also traveled to the Czech Republic to see Terezin to Germany to see Sachsenhausen, Stutthof, Dachau, and Buchenwald as well as to Berlin, Munich, Krakow, Warsaw and Wroclaw to fully flesh out her project and her understanding of the Holocaust. She has been to 18 concentration camps, and remains of forced labor camps. Hannah worked side-by-side with the U.S. Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. for historical accuracy in her research.

Survivor: My Father’s Ghosts

Hannah Kozak was born to a Polish father and a Guatemalan mother in Los Angeles, CA. At the age of ten, she was given a Kodak Brownie camera by her father, Sol, a survivor of eight Nazi forced labor camps and began instinctively capturing images of dogs, flowers, family and friends that felt honest and real. As a teenager growing up in Los Angeles, Hannah would sneak onto movie lots and snap photos on the sets of Charlie’s Angels, Starsky and Hutch and Family, selling star images to movie magazines and discovering a world that was far from reality.

While working in a camera store at the age of twenty, Hannah’s life changed when she met a successful stuntwoman named Victoria Vanderkloot who became her mentor and helped her start a career in stunts. For nearly twenty-five years, Hannah’s work provided the opportunity to work with notable directors such as Michael Cimino, David Lynch, Mike Nichols, Tim Burton and Michael Bay. She worked as a stunt double for celebrated stars like Cher, Angelina Jolie, Lara Flynn Boyle and Isabella Rossellini. On every set, Hannah took her camera to work, capturing candid, behind-the-scene pictures that penetrated the illusion of Hollywood magic.

Her wanderlust and career in the film business afforded Hannah the opportunity to travel from Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Mexico, Guatemala and Peru to Egypt, Italy, Israel and India, capturing images of far away lands and exploring the innocence and truth found in the faces of children from around the world.

Hannah has turned the camera on herself, her life and her world. She continues to look for those things that feel honest and real, using her camera as a means of exploring feelings and emotions. After decades of standing in for someone else, she now is in control of her destiny

and vision.

Hannah creates psychological and autobiographical photographs. Her subjects are the people and places that touch her emotionally. She has been photographing people and places for four decades. Photography has the power to heal and to help us through difficult periods, something Hannah Kozak knows first hand from personal experience.

My father, a Holocaust survivor, was never a victim. His unresolved grief and sadness became a catalyst for ambition. His parents were Orthodox Jews who in my father’s words, “never had money in the bank and lived hand to mouth.” As one of eight children, he was the only member of his family to survive, including his parents and grandparents. Yet there was always a shadow of Poland behind my father.

To achieve their goal of exterminating every Jew in Europe, the Germans created 1,634 concentration camps and satellite concentration camps, seven killing centers and 900 labor camps. From ages fifteen to twenty, my father survived eight of those camps in Germany.

Before the camps, my father was forced into the ghetto, the worst area of Bedzin, Poland. He was allowed to leave the residential district only to do forced labor, working for starvation wages making uniforms for soldiers.

My father was in daily direct contact with death. Starving and weakened yet he didn’t give up hope. He walked with death and lived so that I could tell his story. As I walked the grounds at Treblinka, where his brother was machine-gunned down, I found myself humming Hebrew songs, chanting the prayers of dead souls.

In those camps, my father suffered from Tuberculosis. I remember when we would be driving, he would frequently have to pull over, open his driver’s door to lean his head out and spit.

When Dernau, the final camp he was in was liberated on May 8, 1945, he collapsed at sixty-five pounds. He remembers hearing someone say in Yiddish, “The Russians are coming, the Russians are coming.” He spent a year in a sanitarium called Marine House, a place mainly for people with Tuberculosis.

I have traveled to Poland numerous times to retrace his steps to see the camps he was forced into and the killing centers where his family was murdered. Dernau, in particular, quieted me while awakening every sense. I saw the barbed wire fence that kept him prisoner when he was close to death. I heard crickets and the ever-present singing of birds that seem to sing differently in Poland, than they do in the U.S. I wondered if he could have heard the running water from the creek surrounding the camp. Could he see the tall, sinewy trees? Making it out alive was a combination of his will, his intuition, a bit of luck and a miracle.

My father asked me to tell his story towards the end of his life. I took this as a task. As a 2nd generation survivor, perhaps this is a reason for my existence. I created a short film called Survivor: My Father’s Ghosts as well as a photo essay, which will eventually become a book. These are my love letters to him.

The remains of the war fascinate me even as a cloud of darkness from my father’s past has haunted me since I was ten years old. I grapple to understand man’s inhumanity to man. I understand now; that I will never truly comprehend what happened to my family but my continued sojourns to Poland and Germany, help me to see answers to my questions, in person.

My father Abram Izrael Kozuch AKA Sol Kozak

Prisoner #34 598

Born: Bedzin, Poland July 25, 1925

Transition: West Hills, CA Dec 25, 2012

Timeline in the labor camps from 1942-1945

- Markstädt – Laskovitzeh (1942-1943)

- Klettendorf – Klecina (1943 January to 1943 May)

- Hundsfeld – Psie Pole (1943 June to 1943 December)

- Hirschberg – Jelenia Góra (1943 December to 1944 June)

- Bad Warmbrunn – Cieplice Śląskie (1945 January)

- Erdmannsdorf – Mysłakowice

- Hirschberg – Jelenia Góra

- Dörnhau – Kolce (May 8, 1945) Liberation

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Martin Stranka: All My StrangersDecember 14th, 2025

-

Interview with Maja Daniels: Gertrud, Natural Phenomena, and Alternative TimelinesNovember 16th, 2025

-

MG Vander Elst: SilencesOctober 21st, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Josh BirnbaumOctober 10th, 2025

-

Aiko Wakao Austin: What we inheritOctober 9th, 2025