Ward Long: On Domestic Life

Recently I’ve found myself thinking about the differences in function between a film and a photobook. What I’ve come to is this; when one watches a film you the viewer are being told a story. When one flips through the pages of a photobook, you the reader tell yourself the story. When sitting down with a photobook one has total agency. You decide how long to linger on each image and, despite the lack of sound, it becomes hard not to imagine the aural atmosphere specific to each scene. I can recall the first time I sat down to open Ward Long’s book Summer Sublet. I had recently moved out of a 2 story 3 bedroom house that I had shared with 4 other roommates and a smattering of extended stay house guests. Turning the pages of Long’s beguiling monograph I found myself remembering rather than imagining. I expect I’m not alone in that sentiment. The scenes are familiar and unassuming to the degree that one can’t help but insert themselves into the narrative. The people depicted are perfect strangers to me and yet possess a likeness to so many of those who I’ve shared space with over the years. In our interview Ward had the following to say about how we as viewers interact with prints as opposed to books. “Prints function so differently than books. Public rather than private, always up rather than open and shut, in our shared physical space rather than a portal to a story world.” I couldn’t agree more. Opening Summer Sublet feels like discovering a door in your house that has previously gone unnoticed. You turn the knob to reveal afternoon light shining through a tapestry onto a stack of books. You’ve seen this room before. It belonged to any number of roommates that have since left. You spend a moment simply noticing the way things are and after some time move on, deciding what happens next.

Ward Long is a photographer, artist, and educator living in Oakland, California. His photographs and handmade books chart loss, landscape, and the tenderness of domestic space. Summer Sublet was published by Deadbeat Club Press, and named one of the best photobooks of 2020 by Alec Soth and Vanessa Winship. He received his MFA in Photography at the University of Hartford. He was awarded a Beth Block grant from the Houston Center of Photography and named one of Flash Forward 2019 from the Magenta Foundation. His work is held in numerous private and public collections, including the University of Virginia and Pier 24 Photography.

Summer Sublet

When I lost my lease, Ara said there might be a room on Montgomery Street, and so I moved in with Alice, Hannah, Sarah, Bianca, and Kate. The house was by the art school and the women’s college, and it stacked full of mismatched, unclaimed belongings from several generations of roommates. At first I hid in my room and tried not to be noticed. I was so conspicuously male, and so out of proportion. I never had sisters.

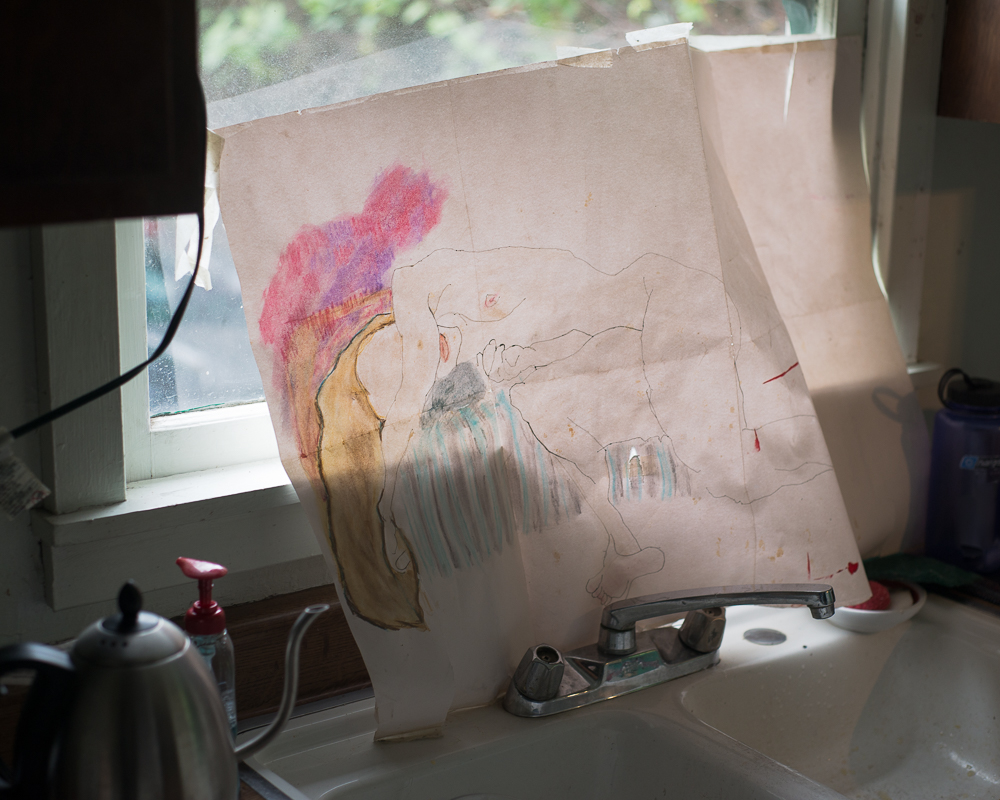

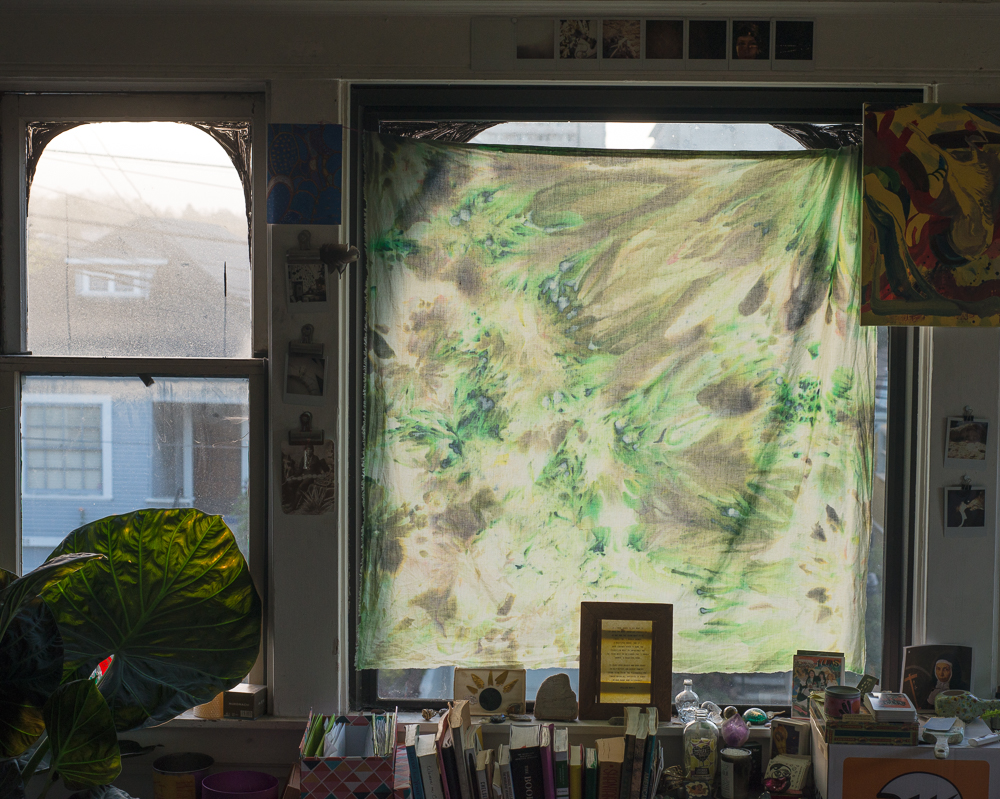

They cooked together, mixed teas and tinctures, dyed fabrics in the backyard, designed costumes for children’s plays, wrote songs and poems, gave each other late-night tattoos, smithed jewelry, and stitched leather. They read tarot, talked aura, charted horoscopes, and parked their dirt bikes in the basement. The everyday physical and emotional closeness completely flooded me. I remember the first night we all said, “I love you,” before bed.

It all started to blur and bleed together. The paintings on the wall became our own poses, the drawings on your body drip back into the books on the shelf. I couldn’t believe the caring touches, the open hearts, the blushes of affection, the care and the clutter. I never wanted to move out.

To begin, I’d like to hear about what initially drew you to photography. What were the first pictures you made? When did it become clear photography was something you wanted to pursue seriously?

The first pictures I made were in rural North Carolina. I was in the depths of the post-collegiate wasteland, and taking pictures was a way to spend time with myself without worrying about the future or who I was supposed to become. I mostly hung out at the campus art library. I lived with my friend Will, and we’d ride around in his ‘66 Mustang that he bought in high school from an airline pilot, and I’d take pictures of strange buildings and pay phones. It was a good way to get started.

The summer after that I moved to New York and worked at a music magazine. I was trying to write about bands and songs that would be cool in exactly six weeks, and one night at the office I overheard the art director talking about references for an upcoming shoot of Daft Punk. He started with The Man Who Fell to Earth, and then moved on to Phillip Lorca diCorcia’s Hustlers, reimagining these French house robots as alienated teen prostitutes dreaming of fame in a LA supermarket parking lot. It was an epic reading of visual culture, a testament to how a single photograph could hold art history deep and wide, a dissertation directly downloaded into the space where my brain used to be.

After that job didn’t turn into a whole life, I moved back to Los Angeles. I didn’t have any friends in town anymore, but I started going to No Age shows at the Smell and at Ooga Booga and meeting people in the punk-post-punk-all-ages-show scene. I’d read about artists and writers in books, but I think this was the first time I was actually seeing a life devoted to art with my own eyes. It stayed up late, it had fun, it didn’t remember the rules. Everything was possible.

The images in Summer Sublet are accompanied by sparse but strong text. What drove the decision to include writing alongside your photographic depictions?

Including the text helped me shape the narrative of the book, and create more context for the images.

I write every morning to clear my head, scribbling until three pages are full. The earliest drafts of Summer Sublet were strings of pictures, linked by color and form more than any sense of story. At some point I started cutting up those journals and taping short phrases alongside the images in a blank notebook. It totally changed the way I thought about the work. The first-person writing added a narrator character, someone who could welcome you into the house and introduce the setting. I could also use little bits of text to reinforce sequencing choices without interrupting the flow of the story or overwhelming the images. I tried type-setting the words, but my quick handwriting in my favorite pen always looked better. It added something to the overall mood, maybe the urgency of those morning pages or the intimacy of a letter to a friend.

Adding the personal writing was also a way to acknowledge my own presence in the space, and to be humble about the limits of my understanding. In photography and visual culture in general, men have a pretty terrible track record of producing images of women that respect women’s agency, independence, and autonomy. When I started thinking about Summer Sublet as a book, I was painfully aware of this privileged gaze and how that would affect the way the images would be seen. With my handwriting all over the book, I think that helps remind the reader that this wasn’t an impartial or all-knowing record of these people, but a personal experience that I had, and one that I wanted to share with you. I wanted people to see my friends as I did, and I wanted to be just as vulnerable as the faces in the frame.

In regards to Summer Sublet what came first, the idea or the images? Can you recall a specific moment when your daily life in the house became a conscious creative project?

The images definitely came first. I was so overwhelmed with the experience, and taking those first timid still lives around the house helped me make some sense of it all. As I got more comfortable, I started taking observational pictures of people. As our friendships deepened, those portraits became more direct and collaborative over time. There was a lot of creative energy in the house, and ongoing collaboration; smithing jewelry, dyeing fabrics, drawing, painting, everything. I started making small work prints to share with my roommates, and then those fed into the next batch of photographs. I think that was the first step towards thinking about these pictures as a discreet project.

The idea for the book only coalesced later. Months after I moved in, thirty-six people died in the Ghost Ship Fire when an Oakland warehouse show went all wrong. Several people in the house lost dear friends, and I lost Ara, the person who brought me to the house in the first place. There was so much sorrow, and so many tributes. After that tragedy, this time in life, these people, and this way of living seemed so much more precious. I felt a responsibility to represent it and get it right.

How well did you know the other residents upon moving in? What were your initial interactions like? Were there specific moments of connection and bonding that shaped the course of your subsequent life in the house? If so please give examples.

I didn’t know anyone at all when I moved in, I didn’t know how long I could stay, and I’d never lived in a situation like this. My friend Ara introduced me to the five women that lived at the house one Sunday morning. Looking back, I wonder why they picked me. At first I felt so awkward and square. I was a foot taller than everyone, and so consciously male. Nothing in the house made any sense to me, so many mismatched and unclaimed belongings, bright jewel tones and half finished projects, six sewing machines in the cabinet and no spare light bulbs.

I felt totally lost. Hannah, Sarah, Alice, Kate, and Bianca just welcomed me in anyway. I slowly opened up to this new world. The images in the book come more or less in the order that I shot them; they move from observational images at a distance to closer, more intimate portraits. Our friendships grew and developed over time, and I wanted the book to recreate that journey for the reader.

It’s hard to pinpoint a specific moment when things changed. I think I was depending on the camera to remember it for me. It was hard to keep track of time in the house. One time Hannah and Sarah rode bikes to meet me for breakfast noodles at the Buddhist temple in Berkeley, and seeing them show up for me made it all feel real in a new way.

In terms of presentation what were/are your hopes for Summer Sublet? Was the creation of a photobook always what you envisioned for the work?

I love photobooks. Holding a book in your hands and turning the pages in your lap can be such a personal, private experience. I made at least ten maquettes and dummies for Summer Sublet, printing every page and then binding them by hand, improving the feel and pacing with every iteration. It was a dream collaborating with Deadbeat Club to fine-tune everything and get all of the production details just so. I think all of that slow and careful work paid off, and it feels like a lot of the intimacy and intensity of the work comes through in the final object.

Prints function so differently than books. Public rather than private, always up rather than open and shut, in our shared physical space rather than a portal to a story world. I was making exhibition prints while I was working on the book, learning more about each image from both forms. A few summers ago I had a chance to show a few prints at the Houston Center of Photography. At the opening, two young women stood in front of the images and started acting out the poses from each photograph. It was the best review I’ve ever gotten. I would love a chance to exhibit more of them. Before the pandemic, I had planned a house show where the framed photographs would be hung in the spots where they were taken, these floating monoliths amidst all of the chaos and life of the house.

Have you always worked close to home, so to speak, or did life on Montgomery street with your 5 roommates redirect your photographic interest? Having since moved out, what does your living situation look like now and how does it affect your way of working?

I’d photographed from my own life before, but never like this. Wolfgang Tilmans and Nan Goldin were early heroes, but they tended to snip phrases and scenes from life, not whole chapters in the first person. Just before Summer Sublet, I wasn’t thinking about portraiture at all. I was making pictures of water-starved hills and end-times red sunsets over the Pacific, trying to understand how California always seems so close to apocalypse or utopia.

Before I moved to Oakland, I made a group of pictures called Stranger Come Home. It was about longing for home & love and the fear you’ll never find either. After a bad breakup, I packed all of my things in storage and lived in ten places in two years. I thought I would make pictures about freedom and movement and life on the road, but instead I made lots of domestic still lives. I was longing for routine, comfort, and safety. It showed. After all of that, the openness and community in the house on Montgomery Street felt like a dream come true.

In a surprising twist, I never moved out of the house. I was supposed to stay for three months, but then Kate prolonged her tour a couple of times. When she was finally headed back, Sarah decided to move out. Hannah left after that, and Bianca and Eric moved out to start a family. So I’m still here, but the house from Summer Sublet is gone. What happens when the Argonauts start sailing their own ships? Is the old boat still the Argo?

That summer of feeling and shooting and seeing was magical, that blend of life and work and creative projects all across the house was intoxicating, but everything ends.

Anything else you’d like to add?

Yes! Shout out to Deadbeat Club. Clint and Alex were wonderful collaborators, and I’m so grateful to have worked with them. You can still pick up the last few copies from them.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026