Photographers on Photographers: Liliana Guzmán in Conversation with Bea Nettles

At the very early stages of my project Next to Myself I had come across Bea Nettle’s Mountain Deck Tarot. I was fascinated by how she used photography to bring the world of the tarot alive in a way I had never seen before, with portraits of people and the natural world instead of drawings. As I continued to research more of Bea Nettles’ work, I felt connected to the stories she told through her own personal experiences of womanhood and how she shared these intimate moments with the viewer. Her photographic manipulations, use of color, and collages gave me the motivation I needed to continue experimenting with images in my own studio practice. Throughout her career, Bea Nettles has pushed the boundaries of photographic experimentation and has elevated women’s experiences, emotions and voice through visual art. I was honored to be able to sit down and talk to her about her photographic journeys and her sincere dedication to artmaking throughout the “spiral of life”.

Bea Nettles has been exhibiting and publishing her autobiographical works since 1970.

Since that time, she has had over fifty one-person exhibitions including the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, Light Gallery and Witkin Gallery in NYC. Her works have also been shown internationally in major group exhibitions. Bea Nettles: Harvest of Memory, a major retrospective opened in October 2019 at the Sheldon Art Gallery in St Louis, moved to the Eastman Museum in Rochester, NY in January 2020, and concludes at the Krannert Art Museum in August 2020. A book by the same name has been co-published by the Eastman Museum and the University of Texas Press.

Her images are in numerous collections including the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Canada, the Polaroid International Collection, SF MOMA, the Phillips Collection in Washington DC, the Eastman Museum in Rochester, NY, and the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona. Her artists’ books can be found in special collections libraries at universities including Yale (Beinecke), Washington, and Virginia.

She taught photography and artists’ books from 1970-2007 at Rochester Institute of Technology, Tyler School of Art, and the University of Illinois where she is currently Professor Emerita. She was selected for the ACE Lifetime Achievement Award in 2019 and the UIUC Art & Design Distinguished Alumni Award for 2020.

Nettles continues to lecture and teach workshops internationally.

Follow Bea Nettles on Instagram: @beanettles

Liliana Guzmán: For my first question, can you talk a little bit about your journey into photography?

Liliana Guzmán: For my first question, can you talk a little bit about your journey into photography?

Bea Nettles:

I was an undergraduate painting and printmaking major at the University of Florida in Gainesville, and we were required to take photography. I was looking forward to that a lot, but it didn’t fit my schedule until my senior year. I walked into the classroom and there was a man named Robert Fichter. I knew Robert because he had also gone to my high school. Robert turned out to be the perfect teacher for me because he already at that point was doing things like cyanotype and painting on photos. He had no problem with it. His assignments were really good and I just jumped right in. By the second or third assignment, I was doing darkroom tricks, you know, blends and negative prints and that kind of thing. I didn’t hand color. It wasn’t until later that year that I started to do that. I took the photo class and then I thought, okay, I’ve got one more elective, I’m going to try ceramics because I hadn’t been able to do much beyond the prescribed regimen. And Robert actually, who was getting ready to leave town, came to the studio and he said Bea, you should really take another semester of photography, you should study with Jerry Uelsmann, he needs a lab assistant. It was a very small program and photography wasn’t even a major at that point, but he needed chemicals mixed and the lab kept open. So I said, well that’s good because that way I could afford the materials and so I stayed on and I worked with Uelsmann the rest of my senior year pretty much independently. During undergrad, I had already begun working on graduate applications and I applied to the University of Illinois where I was accepted into the painting program. I had a difficult time in the photo area- being told that what I was doing was not photography. So I found other ways to keep working. My book Harvest of Memory and The Skirted Garden both document this time in my life. The Skirted Garden (available from LULU https://www.lulu.com/shop/bea-nettles/the-skirted-garden-50-years-of-images-by-bea-nettles/paperback/product-gzrk95.html?page=1&pageSize=4) in particular is 55 years of my work. This book tells my side of the story and it shows samples of the artwork I was making as well as major life events.

Another perk or attraction to photography for me was it was real, or at least possibly began as being real. So any kind of self-portrait that I would draw, wouldn’t have the same gut impact as a photo of myself. Because of your belief that that person existed and that was real. Plus I can’t draw hands!

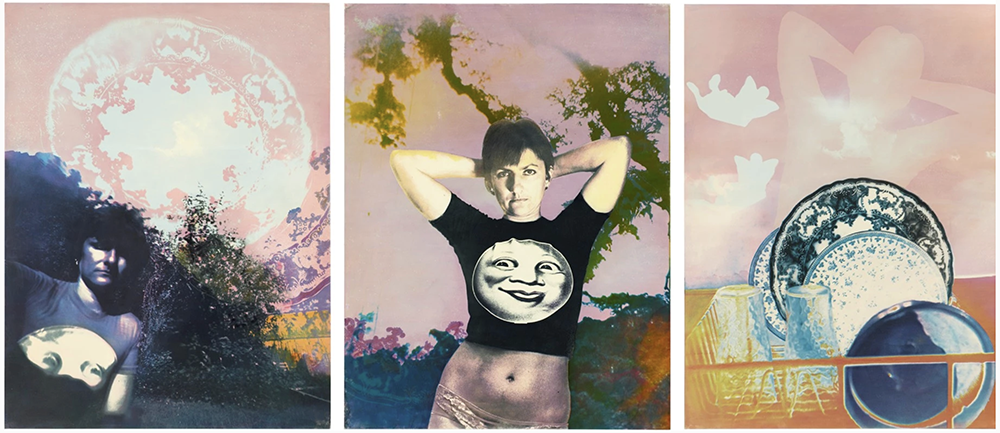

©Bea Nettles: Moon and Dish, 1977; from Flamingo in the Dark. It appears in Bea Nettles: Harvest of Memory.

LG: I have always been drawn to how you have used photography in a variety of ways, whether that is manipulating the photograph through sewing or hand coloring or making artist books and I was wondering how you view the relationship between touch and photography?

BN: That’s a lovely question, especially in COVID times too when touch and human contact and that sort of thing is an issue. I always did like the handwork. I think that the training I had in painting and printmaking helped since that is what you do. You use your hands. Not that it was lacking in photo, I loved the trays and the rinse waters and all of that. It still was rewarding to get in there with a pencil and paint, stitching eventually on the sewing machine, and finding other ways to fabricate images. I had begun to make artist books. I had done books in the seventies that were very tactile. They had transparent overlays, some of them had fiber instead of paper pages. A couple of them had gold screen printing on them so that when you turn the page they’d flash. I was always conscious of the tactile qualities of a book.

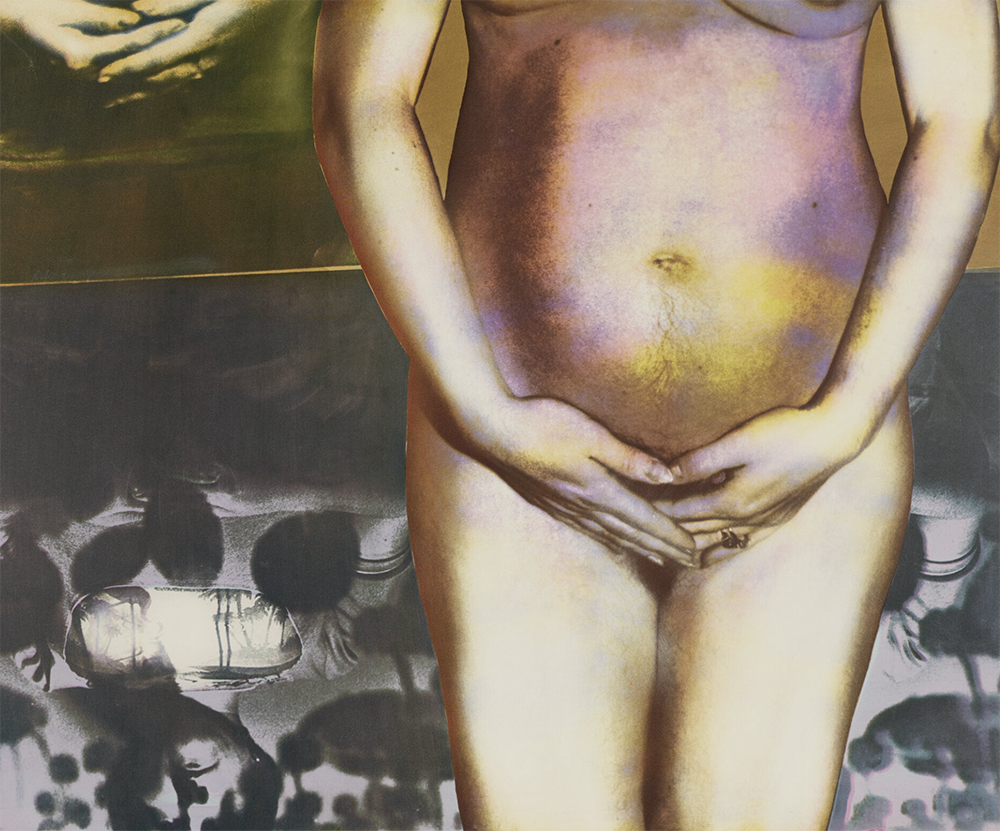

LG: Much of your artwork is autobiographical and focuses on topics such as the female body and experience. As you began working in the late 60s and 70s, during a time when women were advocating for rights and bodily autonomy much like today, how did these challenges come through or find their way into what you were making?

BN: Complexities was done in 1990 and it was all about being a mother, an artist, and a teacher, and having three conflicting jobs and juggling them all the time. I had written more text in that book than I had before and and there is one section on choice, abortion. There is a direct reference to the Clarence Thomas nomination being affirmed and how that day I had absolutely terrible vertigo and this didn’t contribute to my wellbeing listening to the accusations being made and the fact that the woman wasn’t being believed. I write about my fear of losing choice, which at that point seemed possible. And of course it’s happening now. Big time. I did Complexities when I was about 40, I talk about being a mother and I technically could have still gotten pregnant at that time. I said, knowing what I know now about being a mother, would I do it or would I not? But I already had two kids. I contrast the good and the bad of all of that and say, regardless, it should be up to me to decide. Once a woman has had a child, even if she gives it away, she’s been changed forever. Even an abortion would change you forever.

Working with women’s issues goes back before the nineties, but I didn’t consciously call my work feminist in the early seventies. It was autobiographical. That’s what I knew best and that’s what I was going to make art about.

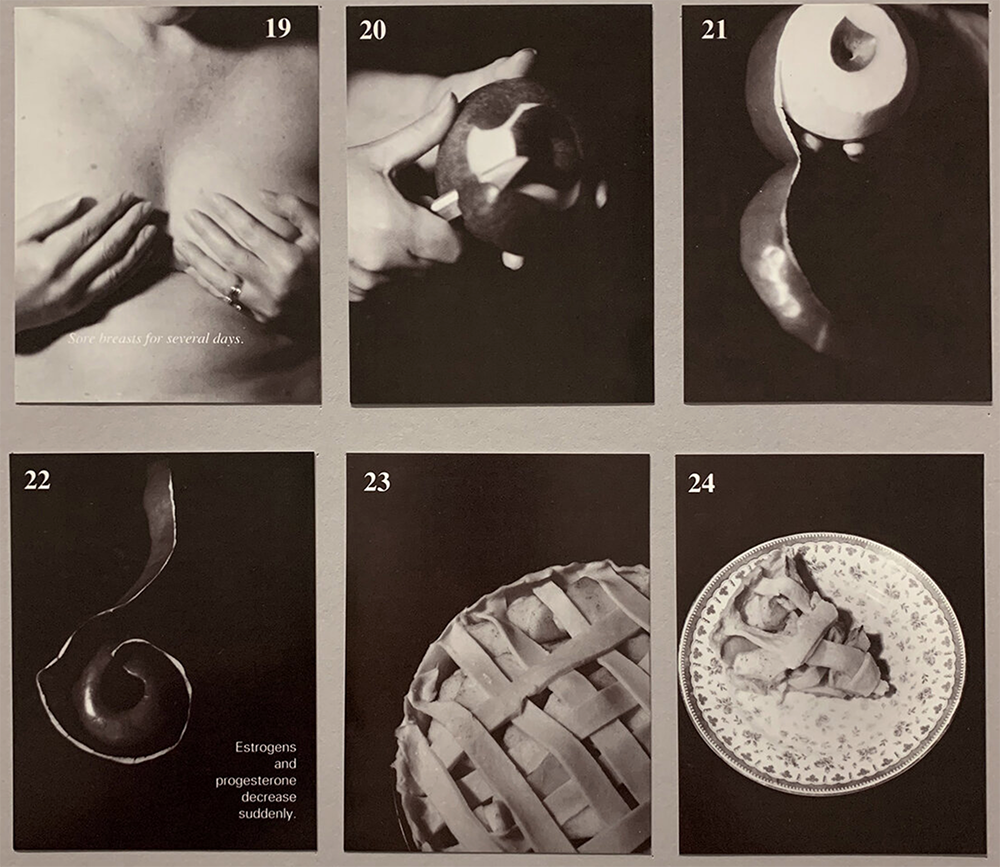

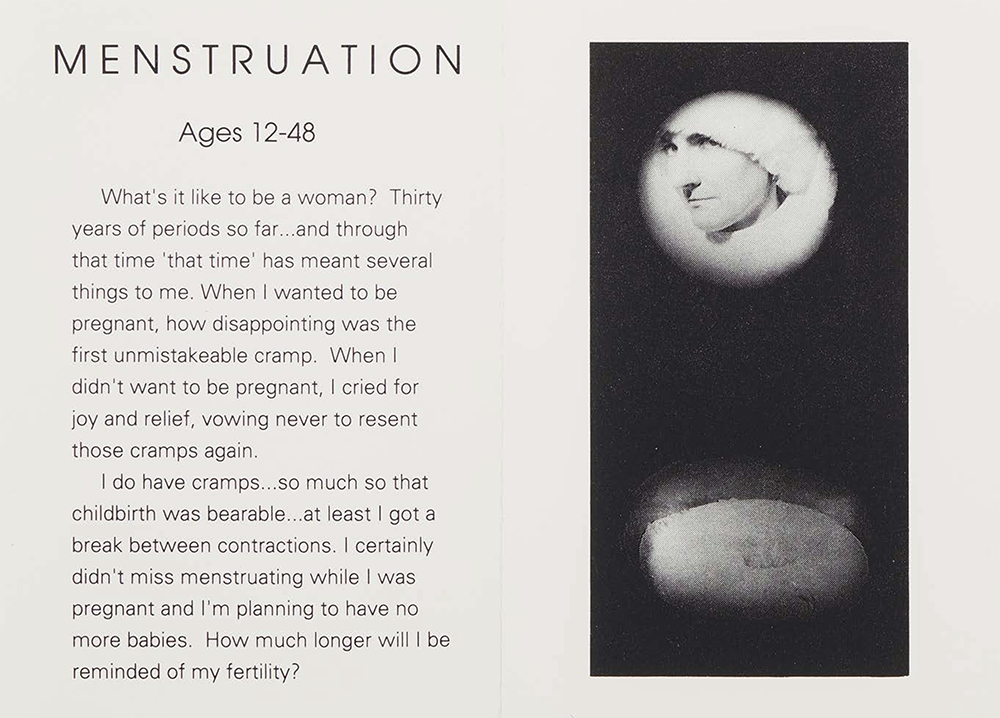

In March of this year, the Henry Ransom Center released a collection of in-depth conversations called: Collecting Conversations: Five Women in American Photography. This includes conversations with me, Betty Hahn, Joanne Leonard, Joan Lyons, and Susan Ressler. These other women talk about how we had mixed feelings about being put in “women’s shows” being “women photographers.” I’m just a photographer and I’m not necessarily a woman photographer. I advocated mainly in my work, which I thought was pretty honest and gutsy, like 28 Days: A Deck of Cards which was about menstruation and never had a show. Not that I knocked myself out trying but I did propose a couple of ideas and people just wouldn’t even go anywhere near it as a topic.

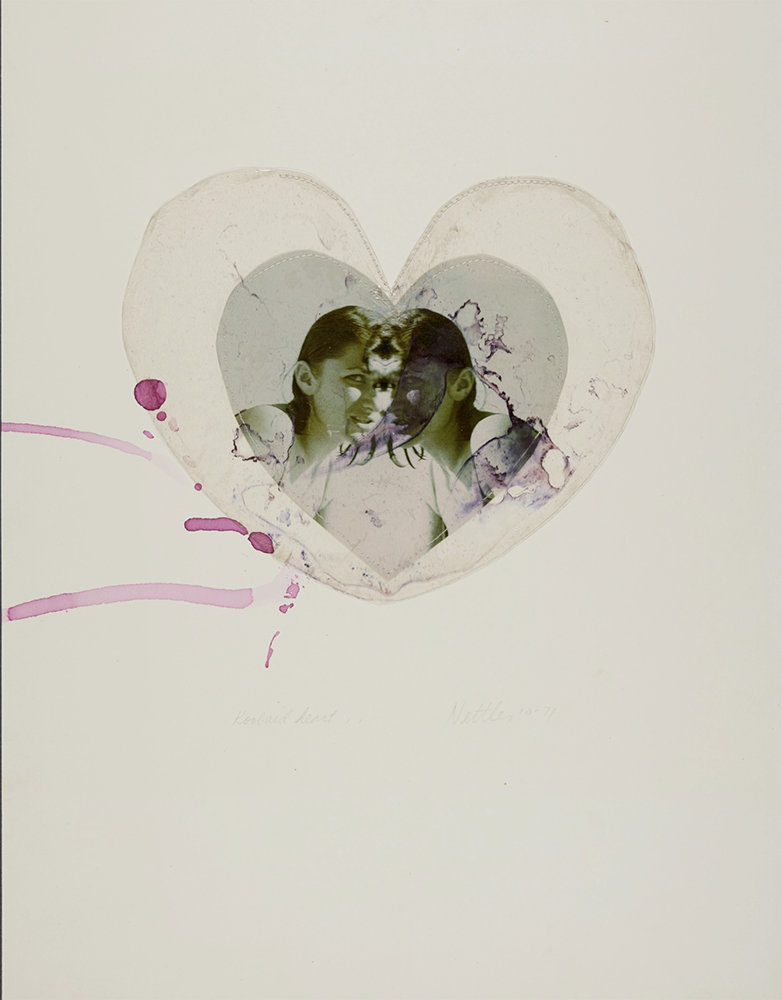

©Bea Nettles, Reflection Pool II, 1979, from Flamingo in the Dark. Gum bichromate print with applied color. George Eastman Museum, gift of the artist.

LG: While we’re still on the topic of women’s experiences, there are many pieces of yours that deal with “the phases of a woman’s life” for instance Moon Sisters as well as your book Flamingo In the Dark. I wanted to know what draws you to create based on events and moments in your life that are so close and personal to you?

BN: Well, it’s because I know about it, I can speak with authority. Of course there were times in my life when I had little children and I couldn’t go off and do a photo tour to China or something. I had a lot of time constraints. There was a pinhole body of work called Close to Home and those were all done when my kids were little. I would steal their ideas basically and the things that they would make and then make these tableaus and shoot them with a pinhole camera and one-of-a-kind Kwik print images.

I always had to adapt my working method to things like time, money, and other constraints. They aren’t necessarily a bad thing. There were plenty of constraints that made it clear to me that what I made was enough. I couldn’t afford it anymore or that was the best that process I could possibly do. I think in some ways it’s harder when you have too many choices, too many options.

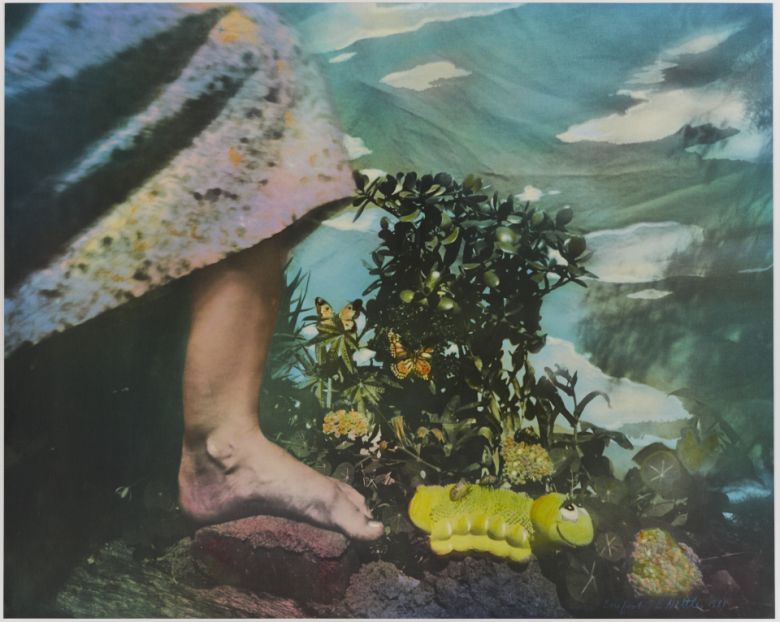

©Bea Nettles, Barefoot, 1981, from Close to Home. Gum bichromate print with applied color. George Eastman Museum, gift of the artist.

LG: Mountain Dream Tarot was my introduction to your work and when I researched more into how this project was created I was excited to see that you quite literally dreamt up the project. Can you elaborate a little bit about your creation of Mountain Dream Tarot?

BN: I had started the Tarot in 1970 but it took five years to get all of the parts! It was like a scavenger hunt that I would revisit every now and then. I wasn’t doing it constantly, I had lots of other things that I was doing but if something was on fire, it was on fire. If someone was in a boat, they were in a boat. You needed swords…it took time to get all of the props together. Also models, I used my family a lot. Towards the end of it, by 1974-75 I wasn’t near my family, I was in Rochester. I would wait until I go to Florida and photograph my parents and family members.

LG: Speaking of dreams, I love that working with alternative processes, adding color to photographs, collages etc. creates a kind of dream-like quality, put together by the subconscious. I was wondering what roles dreams have played in your work, do you record your dreams?

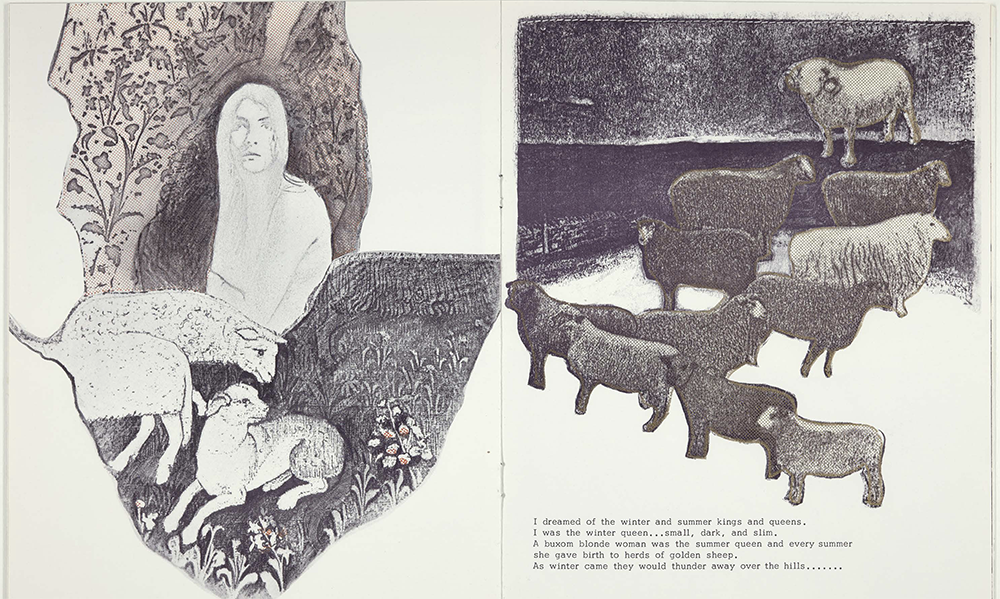

BN: For a while I did record my dreams, when I slept all night. Now, I’m getting older and wake up a million times. So when I would wake up after a full night’s sleep, imagine that, I might still have a dream fresh in my mind. For a couple of years I kept a dream journal and I did scribble them down. I made an offset printed book in the mid 70s called Dream Pages. Included was a dream of a flock of golden sheep on a hill which flashed gold in the dream so the way I did that is I screen printed little halftone dots of gold on them. When you look at the image straight on, it doesn’t look like much but when you turn it, it catches the light and then they flash.

LG: Thinking about projects that take quite a bit of time, what advice can you give to artists, who are working on a long-term project and who are maybe having a hard time making progress? As a recent graduate student, making artwork outside of school definitely presents itself with new challenges!

BN:

Well, when you’re a student, a lot of it is really rapid and often in response to an assignment, there are definitely time constraints. After grad school and I always had ideas and projects—often it would be a process or a product or something that I would be curious about and think, how can I make this thing work for me? And that would be what would start it. Sometimes it was a different idea. But out of grad school, my first teaching job, I had five class preparations, so it was murder. I had never taught before so there was very little strength left in the evening to do much of anything. I continued to make hand-colored toned photos. But after a few years, I had a creative block for the first time, and it was frightening. Eventually I realized, this is going nowhere, I’m starting to imitate myself. I would think “oh that looks like a Bea Nettles” and I don’t want to do that, it’s not interesting to me. I didn’t know what the next step was going to be, it was panic inducing. I thought it was over! I thought, I thought I was an artist but I guess not. Now I expect that it’ll happen. Sometimes the transition is easy and sometimes it’s enforced from the outside. There are lots of reasons to stop doing something and sometimes starting is by accident. Sometimes it is something that I’ve been working on all along, but I don’t realize that I’ve been working on it until I can name it. Once I have the name of the book or the body of work, sometimes I’ll write it down or stick it on the studio wall. It’s bringing something from the subconscious, I don’t want to get too new age on you, but that’s how it works sometimes for me.

Seasonal Turns is a really good example of that. I did it in 1998 and prior to that I had done the project Turning 50 in 1995. Turning 50 was so easy, once I got the idea, I already had a lot of triptychs made and it popped together quickly. But creating Seasonal Turns took three years of, not floundering, but I was really struggling. I remember sitting at times with my sketchbook writing and writing, trying to figure it out. When I got this idea about the four seasons and extending the triptych longer, seven, like seven days of the week…as soon as I got that idea wham! They just went together.

LG: This question also is a good segway into viewing success and especially during times when you might be comparing your own success and output to others which is something that is so easy to do with social media these days…

BN: In my book The Skirted Garden I talk about different ways of achieving professional success and the models that we’ve been given, like the one of a pyramid, of upward momentum, as in the ladder of success. You start at the bottom and achieve a peak. That just doesn’t work for a lot of women. You stop because you have a kid, you stop to care for elderly parents, you are constantly being sidetracked. The image of the web is more appropriate than the image of the pyramid. There are divergent paths, even a spiral to a certain degree.

For achieving success, I think today the stakes are higher, there’s more competition. I had some incredibly lucky breaks in my time- and it wasn’t all luck. A lot of it was that I had interesting work. I had work that nobody had ever seen anything like, and I had a lot of it. That’s the thing, you have to back up what you’re showing, it’s a long, long commitment and it’s not something that is done rapidly. It takes time.

There’s no doubt that networking and mentoring is important. It would be ridiculous to say that I got where I got on my own steam because that wouldn’t have happened. I mentioned Robert Fitcher because he was such a generous soul in the way that he had helped. There were other mentors in my life too. Good teachers do that, they help their students when they can. The trick is to keep working and have the work to back it up.

LG: I’d like to know what you have been working on in recent years and how that has perhaps changed from the projects you had done earlier in your career?

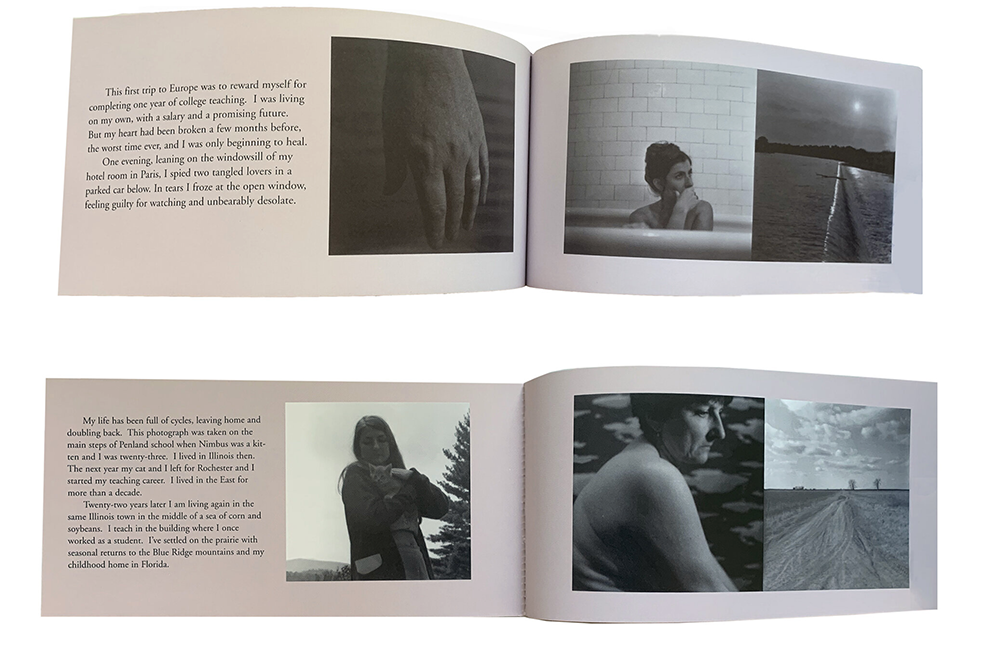

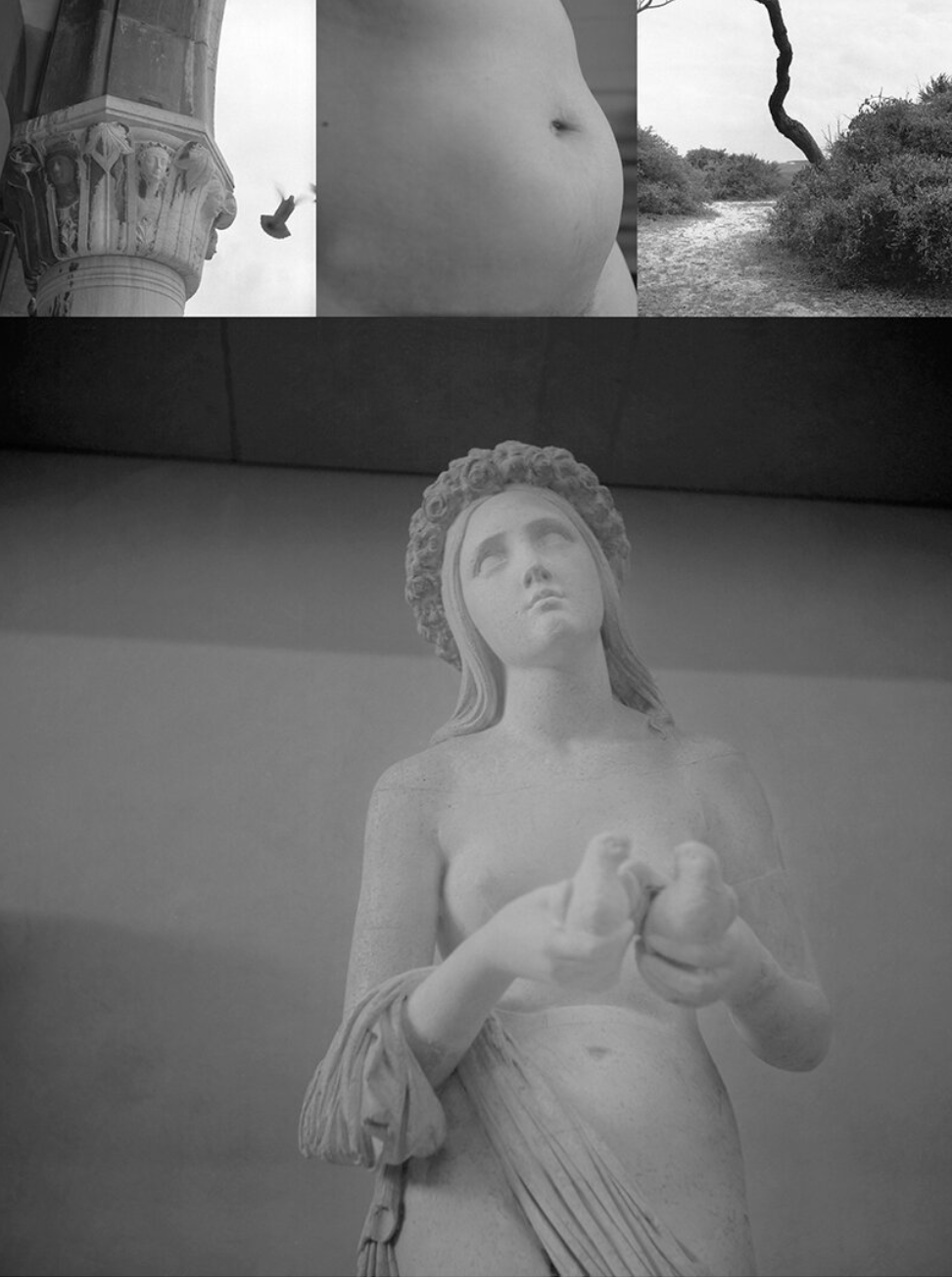

BN: The last nine years of my work was, ironically, was not manipulated other than being engineered on a computer. It’s called Return Trips. Those were the last rolls of 2 ¼ film that I used and I would put together three across the top and one at the bottom. Nine almost ten years of that and nearly 100 of them were made. It was all complete, full frame, unmanipulated black and white photography, so it was funny to kind of wind it all down and go back to absolute basics…with the exception that it wasn’t just a single photograph in isolation, it was about image relationships. I talk more in depth about that in my Art & Design Distinguished Alumna lecture that I did at the University of Illinois. The relationship between pictures is fascinating and that interest of mine really came from an understanding of sequence and photo books. The way that pictures affect each other. Return trips dealt with all sorts of themes like nostalgia, going back and not being able to get quite where you were before.

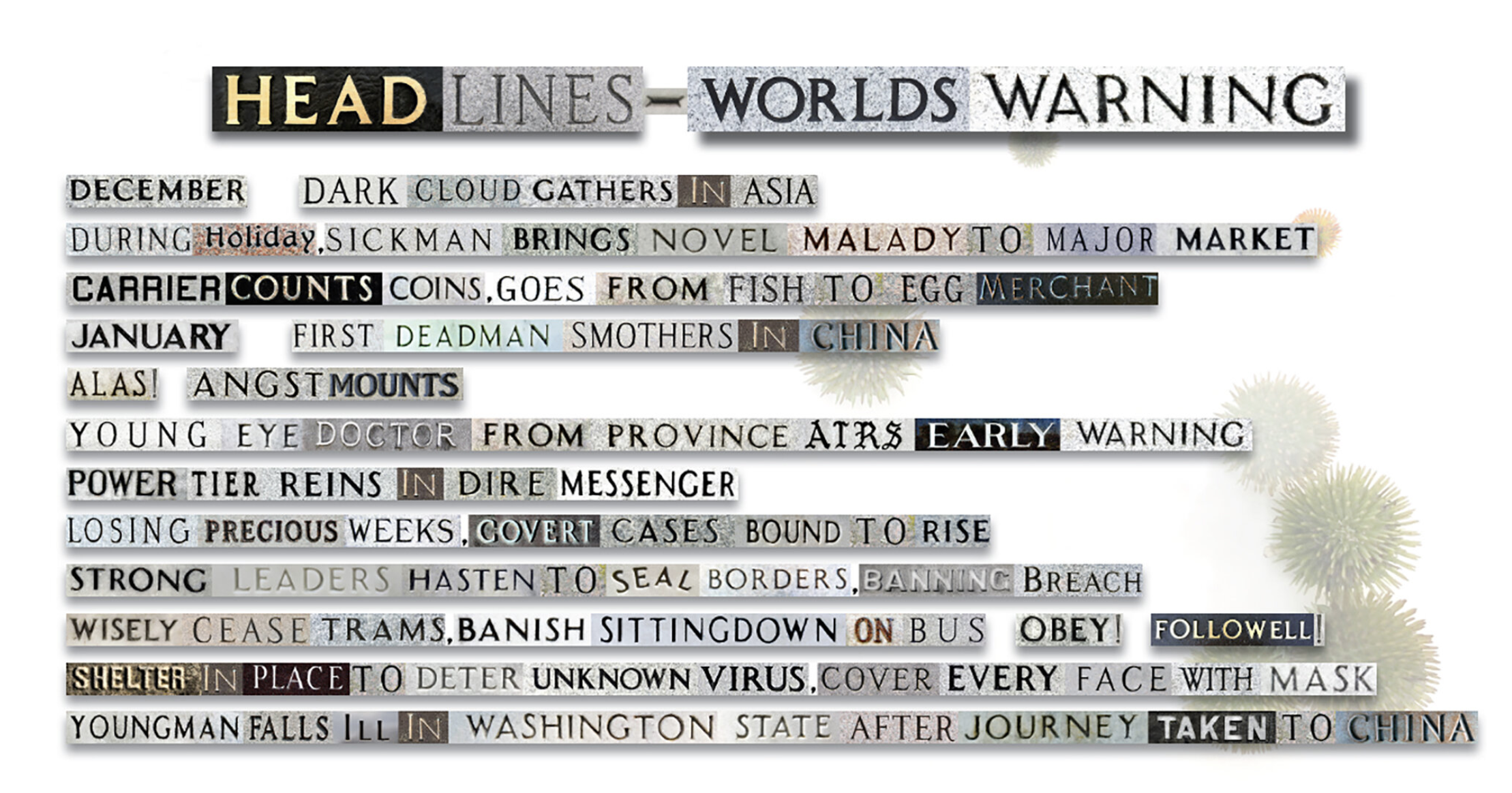

After Return Trips I started to think about people’s surnames that I found in cemeteries and I have collected almost 7,000 of them with a cell phone. I could have never done this pre-digital. With these names I have created several poetry books which can be found on my website.

The last one I made was at the beginning of COVID. I wrote about the first year of COVID in people’s last names Head Lines: Worlds’ Warning.

LG: Lastly, I think a lot of artists today and really trying to find a balance between making and producing a lot of work and also taking time to practice self-care which is also an important part of being a working artist…

BN: Oh yeah, some busywork, get down to the studio, clean it or whatever, just be there. But also you can give yourself a break! You don’t have to beat yourself up, go out and pull weeds!

LG: Thank you Bea so much for talking with me and it was a joy to learn more about your work, process and projects!

BN: Thank you!

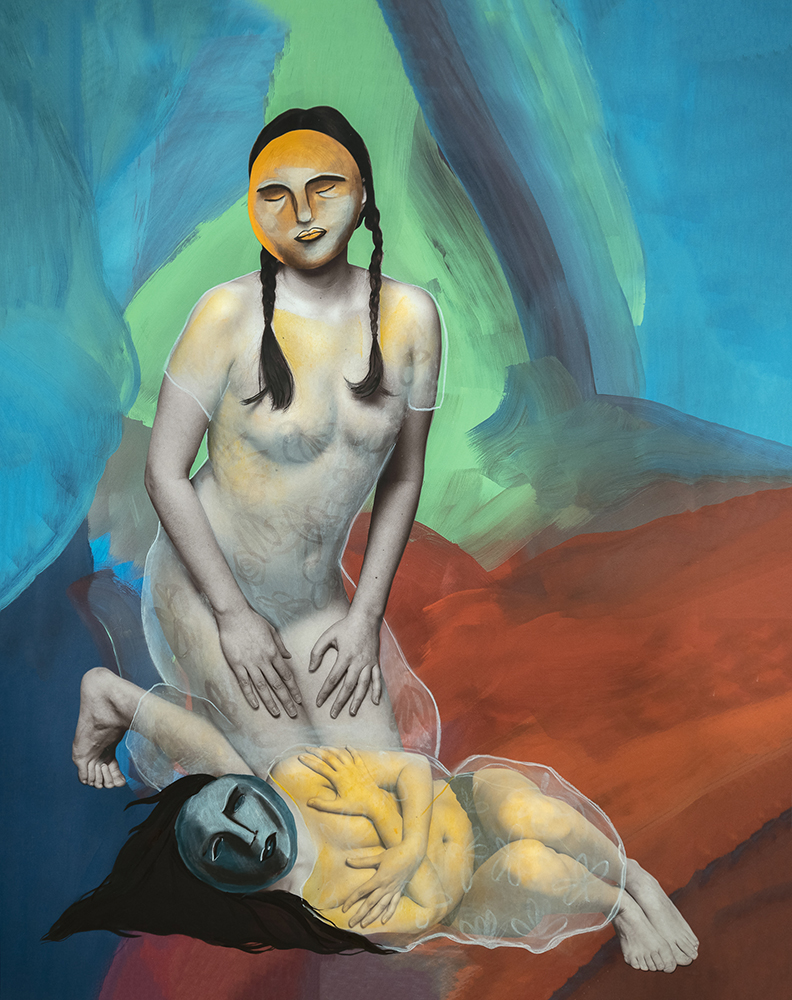

Liliana Guzmán is a photographer and painter whose artwork entwines topics of the body, memory, sexuality, and the hidden landscapes of the self. Born in Baltimore, Maryland and raised in Indiana, Liliana completed her BA at Earlham College with a double concentration in Photography and French and Francophone Studies. In May of 2021, Liliana completed her MFA in Photography at the Eskenazi School of Art, Architecture + Design at Indiana University Bloomington.

Her photographic practice incorporates a wide range of techniques and mediums from film photography and alternative processes to digital photography, painting, and drawing. Through the recurring subject matter of hands, touch and gesture, Liliana’s artwork expresses touch as not only a formative and intimate experience but as one that establishes both internal and external connections within ourselves and those around us.

Most recently she has exhibited at the Soho Photo Gallery, the Indianapolis Art Center and Manifest Gallery where she was a finalist for the Manifest Grand Jury Prize for 15th exhibition season. Her series Next to Myself was recently exhibited in her first solo exhibition at the Amalie Rothschild Gallery at Creative Alliance in Baltimore, Maryland in May of 2022.

Follow Liliana Guzmán on Istagram: @lilinessy

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi NguyễnDecember 8th, 2025