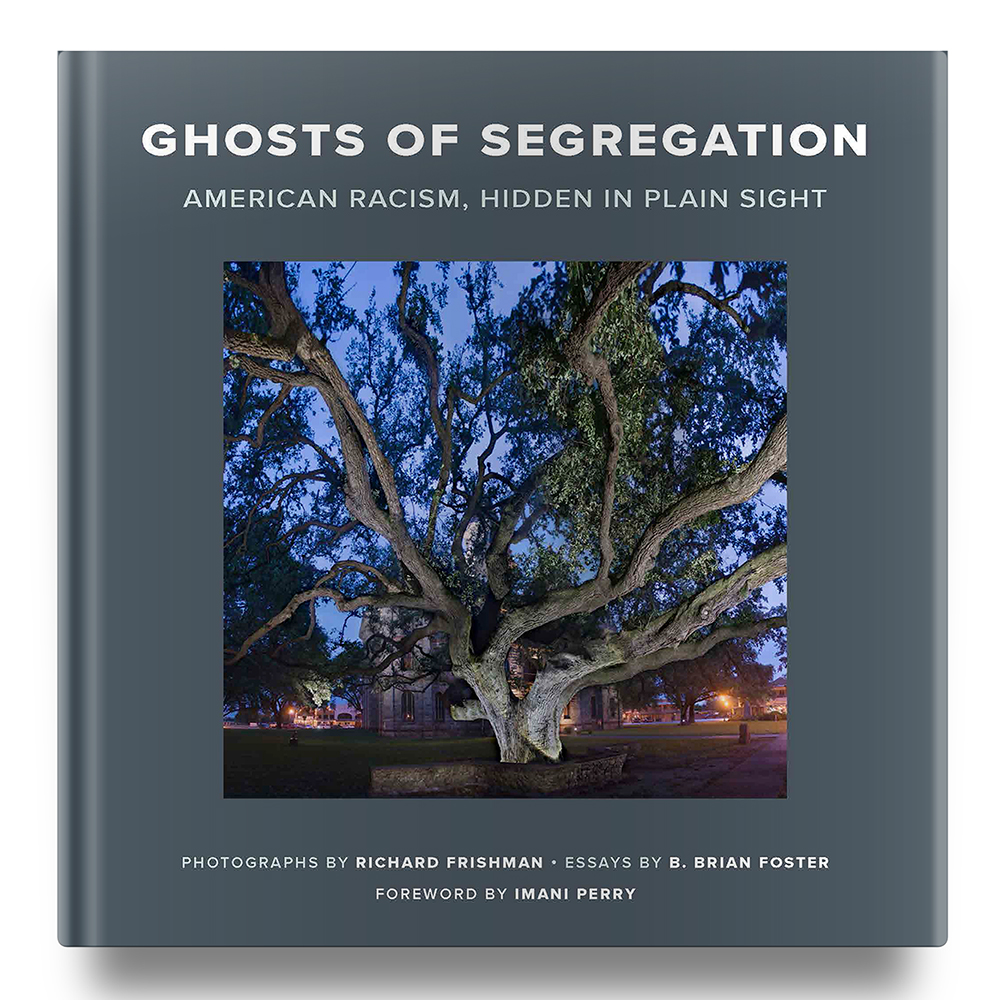

Rich Frishman: Ghosts of Segregation: Racism, Hidden in Plain Sight

Ghosts of Segregation photographically explores the vestiges of America’s racism as seen in the vernacular landscape: Schools for “colored” children, theatre entrances and restrooms for “colored people,” lynching sites, juke joints, jails, hotels and bus stations. What is past is prologue. Segregation is as much current events as it is history. These ghosts haunt us because they are so very painfully alive. – Richard Frishman

For many years, I have appreciated the work of Richard Frishman. An award-winning photojournalist, he looks hard at the United States as a storyteller, documentarian, detective and historian. With the help of a Guggenheim Fellowship, Frishman completed a 35,000-mile journey around the United States, capturing photographs of structures like the New Orleans Slave Exchange, old “colored entrances” at movie theaters in Seattle and Texas, formerly segregated beaches in Los Angeles, and the former site of New York City’s slave market. Foster, an acclaimed writer and professor of sociology at the University of Virginia, enhances and contextualizes the collection with seven essays of stirring prose and intimate storytelling. His writing adds layers of emotional resonance and sharp insight to the photographic collection by speaking to the shared memories, living histories, rippling beauty, and ongoing struggles of Black life in the United States. The result in a profound monograph, GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION: American Racism, Hidden in Plain Sight, published by Celedon Books . The book is co-authored by B. Brian Foster, PhD, who is a writer, storyteller, and sociologist from Shannon, Mississippi and includes a Foreword by Imani Perry.

This haunting collection of photography and essays illuminates the lingering architectural and geographical remains from America’s history of segregation, slavery, and institutional racism.

An essay by the author follows.

The New York Times featured Frishman’s work in an extensive article in 2020, and the project has been shown in galleries around the country, receiving acclaim and recognition–including a Guggenheim Fellowship and Pulitzer Prize nomination. The book brings the striking collection to the page. Combined with Foster’s stirring prose and intimate storytelling, GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION reveals how our surroundings bear witness to history, reminding us where we have been, where we are now, and crucially asking where we go from here.

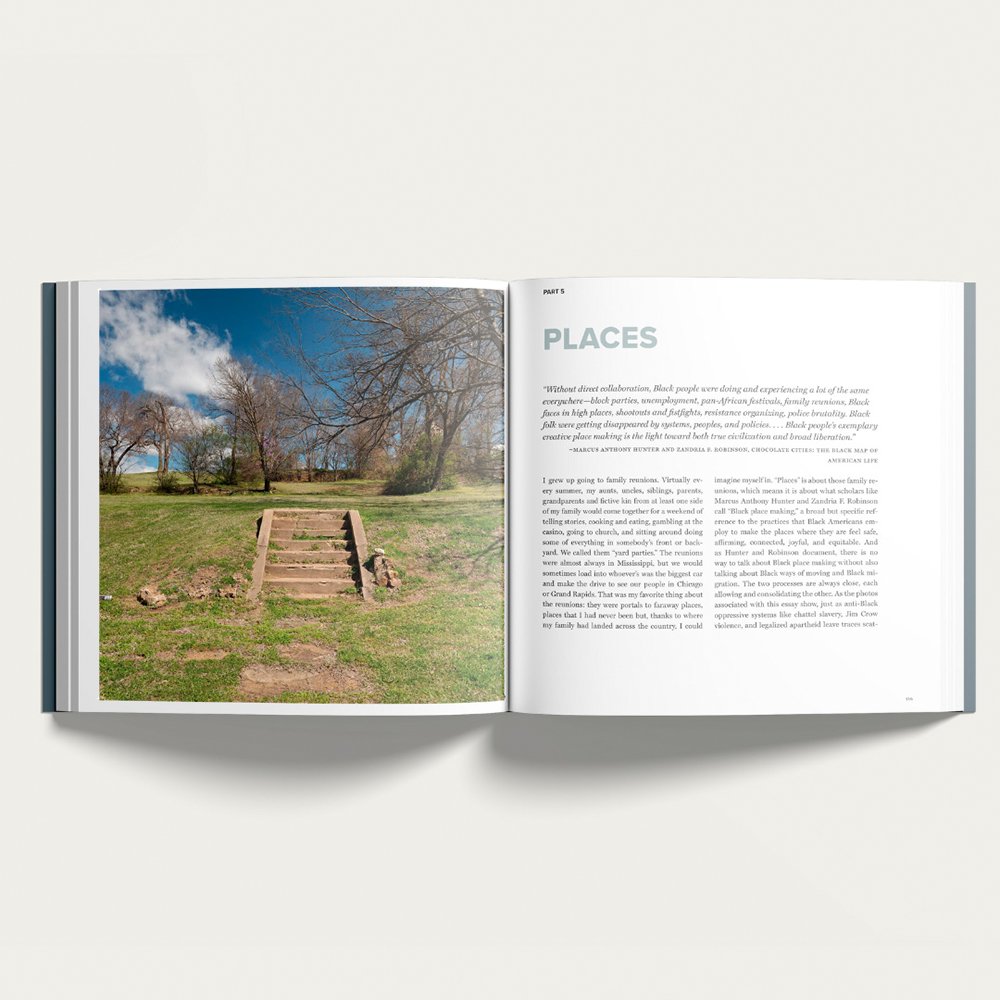

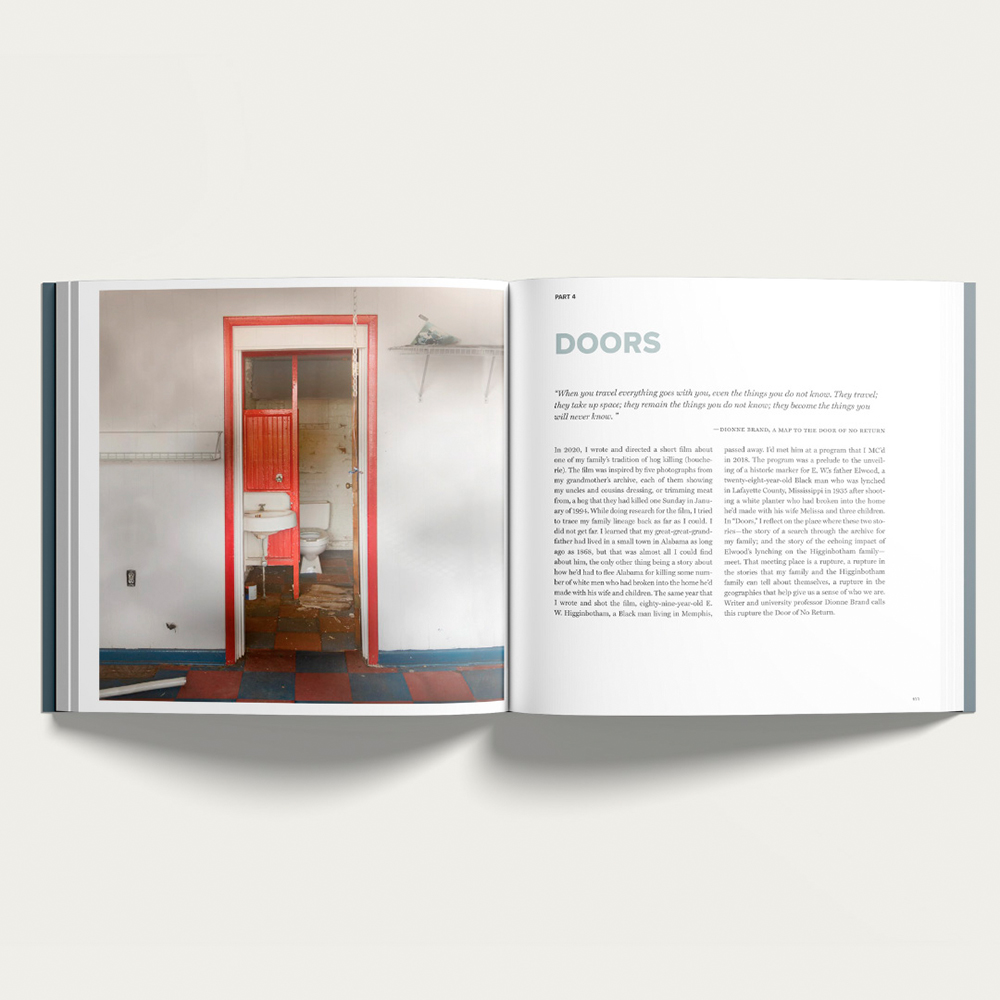

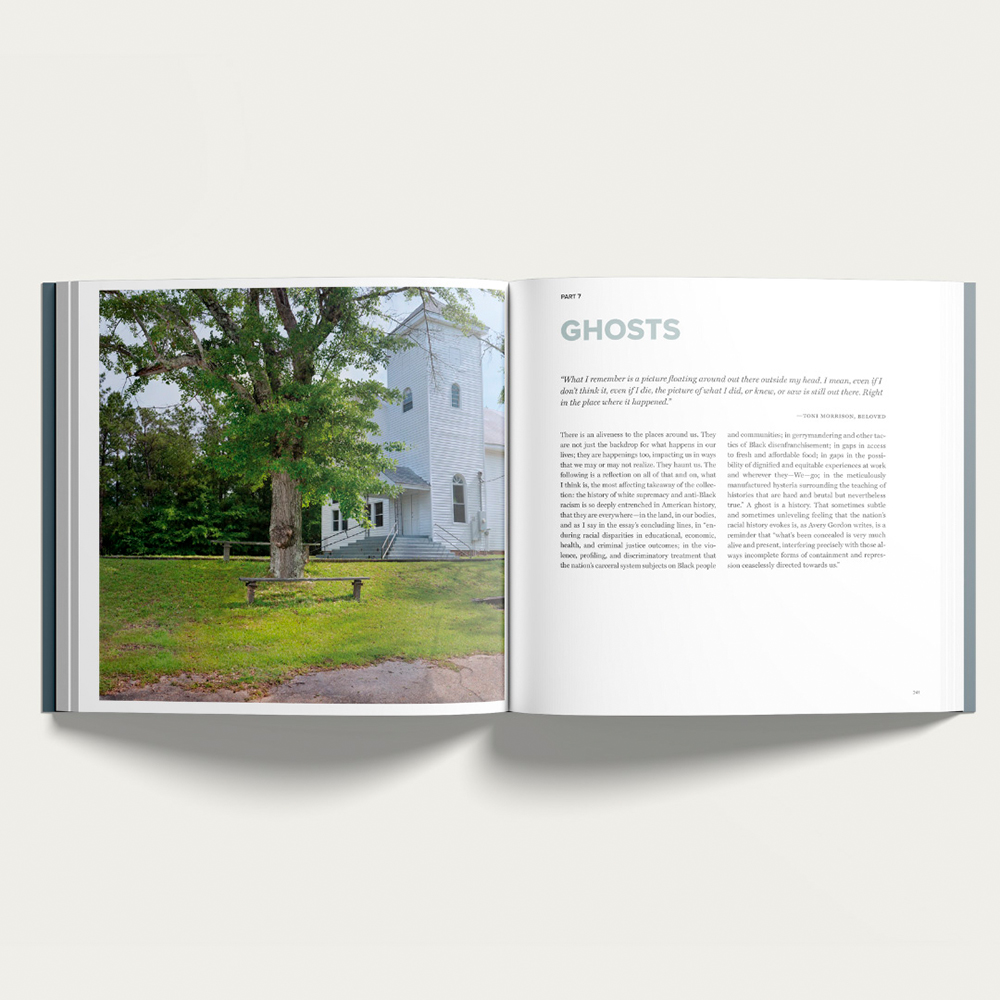

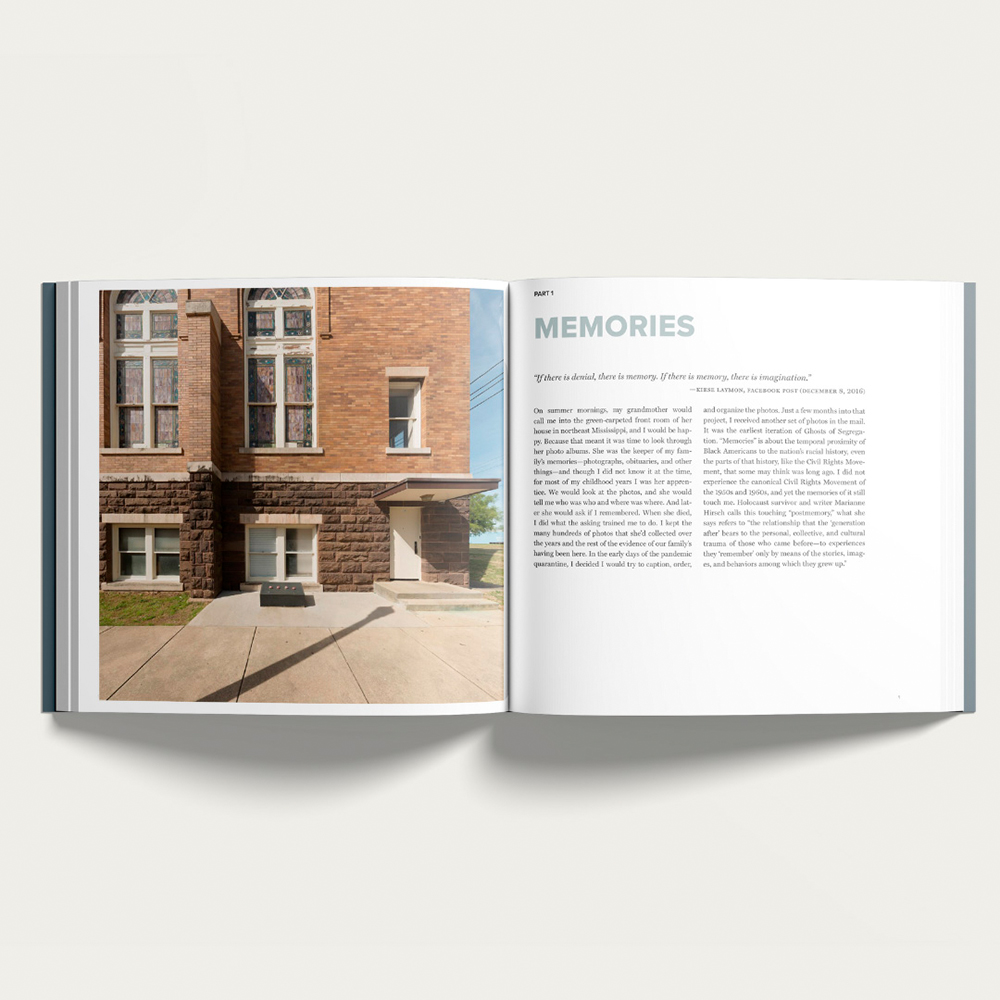

Spread from GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION: American Racism, Hidden in Plain Sight By Richard Frishman and B. Brian Foster

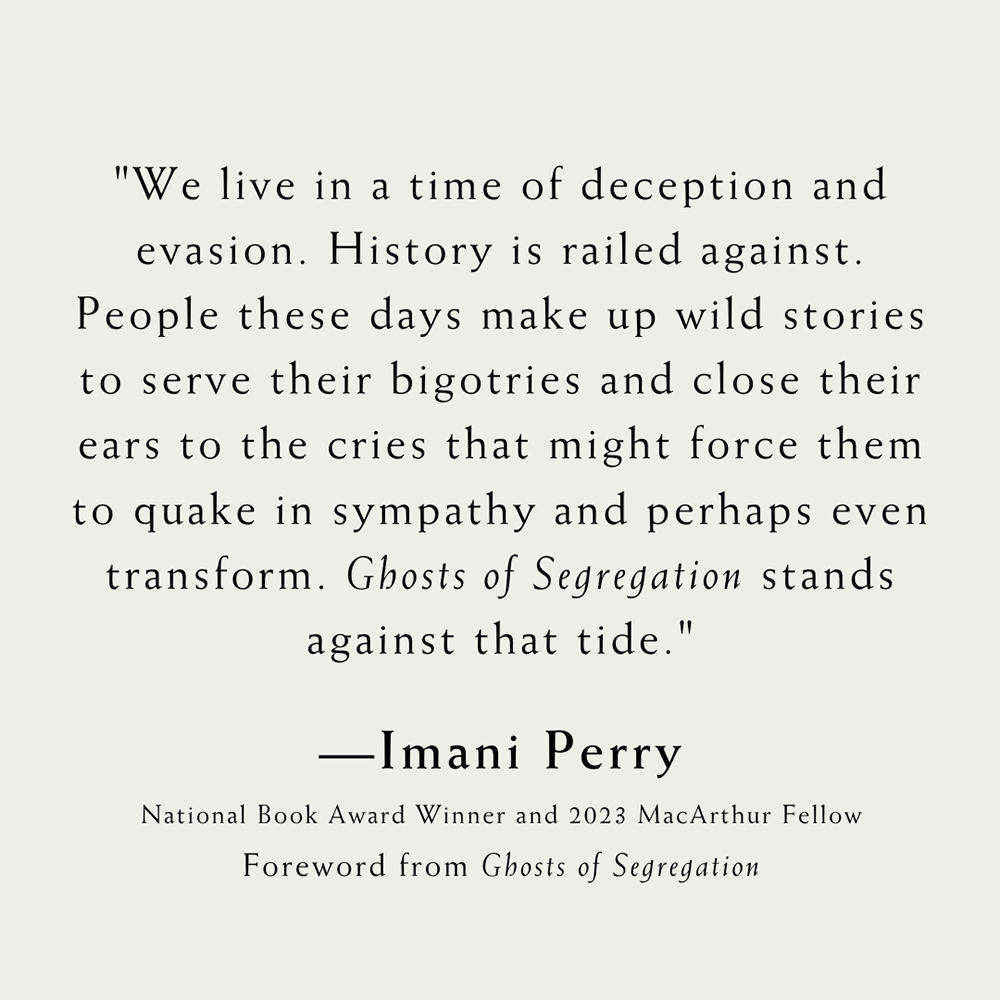

“You’ll notice new relationships each time you open these pages—between Foster and Frishman, across the color line, between the past and the present, and between you and where you’re situated in the world. You’ll be encouraged to recommit to a better set of human relations. Come walk with the ancestors, the truth tellers, the survivors, and witness humanity. It’s a trip you won’t forget.” — Imani Perry, National Book Award-winning author of South to America and 2023 MacArthur Fellow

Spread from GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION: American Racism, Hidden in Plain Sight By Richard Frishman and B. Brian Foster

Spread from GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION: American Racism, Hidden in Plain Sight By Richard Frishman and B. Brian Foster

Spread from GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION: American Racism, Hidden in Plain Sight By Richard Frishman and B. Brian Foster

GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION: American Racism Hidden in Plain Sight

When I drove out of our driveway on August 7, 2021, I was unaware of the magnitude of the challenges down the road. I only knew that my next stop was Portland, Oregon. The great beyond was vast and the route circuitous; my list of over 250 locations extended across the country.

The passion project on which I had been toiling for three years, Ghosts of Segregation, was being published by Macmillan in 2024. I was partnered with a gifted Black scholar and essayist, B. Brian Foster. I had received a Guggenheim Fellowship to help fund the book’s completion. Now I was beginning the final photographic road trip to document overlooked vestiges of racism in America. My plan was to be home by Christmas.

It didn’t work out that way. My pride of purpose, at first a burning fire, slowly faded into ashes. Four months down the road, I had only covered 12,000 miles: half of my itinerary, 117 lonely nights in sub-$50 motels, eating Subway sandwiches for most meals, my body atrophying from lack of exercise. I had just made it to the Atlantic shore of Virginia, and I could barely ascend the five little stairs to my friends Kathy and David’s front porch. And that required a cane. My mental and emotional condition were equally painful.

I didn’t realize the state I was in. My dear friend Michelle had tried to intervene, cautioning me that I needed a break, but I am a willful SOB and refused. Several weeks later, David and Kathy more forcefully pressed me to pause, and my wife and son voiced the same urgency from back home. Seeing that my work was suffering, not just me, I relented. My Honda CR-V remained on the street outside the Moran-Griffin bungalow for 6 weeks, while I flew back to Seattle. Rapid recovery required medical intervention, along with intensive physical and mental therapy. When I returned to Virginia, I had to promise my wife and son that they could intermittently join and assist me. It is hard for me to ever admit that I need help.

From NOLA, the plan was to first ascend the Mississippi Delta. One of the most anticipated and dreaded scenes was coming up: the barn in which Emmett Till had been tortured and murdered. Finding the exact location and getting permission from the new owner had taken four years. Emmett’s horrific lynching was a key catalyst in coalescing the modern Civil Rights movement. Honoring his brutally short life was immensely important. Having a capable, concerned, and energetic assistant was a necessity.

We arrived on the afternoon of March 26 to pay our respects, to study the scene, and plan our approach. We began photographing that evening. The picture needed to be shot at night. The horrors experienced by Emmett all took place at night, beginning with Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam kidnapping him at gunpoint from his great-uncle Moses Wright’s home on Dark Fear Road, to his desecrated body being tied to a cotton gin fan with barbed wire and dumped into Black Bayou.

©Rich Frishman, from GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION, HOLY ROSARY CEMETERY; Taft, Louisiana Along the Mississippi River near New Orleans, the tiny town of Taft, Louisiana, began as a sugarcane plantation. Now it is one of the most southerly locations of the polluted region known as “Cancer Alley.” In 1811 some 500 enslaved people revolted, marching past here toward New Orleans in the largest slave uprising in US history. Many were executed, their heads placed on pikes along the river road as intimidation and assertion of white supremacy. After the Civil War, many newly emancipated slaves remained working the fields as sharecroppers. Taft was Our Lady of the Holy Rosary Catholic Church’s original site, serving Taft, Killona, and Hahnville. The church was built in 1877. Union Carbide, developing the surrounding chemical plant, moved the church and most of the town in 1966. The Holy Rosary cemetery and Green Hill cemetery remain the sole relics of the community. The graveyard was still in use in 2022.

Returning to the southbound road, I eased back into Ghosts with unusual trepidation. I felt pressure to complete my photography before another burn-out, and production deadlines were just over the horizon.

For the next month I wandered through Virginia, the Carolinas, Tennessee and Alabama, accumulating evidence. Empty plinths punctuating Richmond’s Monument Avenue. The Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, the Walnut Street bridge in Chattanooga, site of Ed Johnson’s horrific lynching, the birthplace of the first Ku Klux Klan, the Greyhound bus burning site in Anniston, Alabama, and on and on. Already, the stress had caused me to crack a tooth.

What I was documenting represented pain and suffering far worse than I was experiencing. I was also honoring sites of triumphs and celebration, courage, and tenacity. My colleague Brian had reinforced my understanding of the dynamic range of Black experience in America. The history I was chronicling was not monolithic. The guilt I felt, for what my white brethren had inflicted, needed to be tempered with recognition of the triumphs that succeeded in an environment of bigotry.

Places like The Mother-In-Law Lounge in the New Orleans’ Tremé neighborhood, The Sunset Café in Chicago’s Bronzeville community. Alabama’s Africatown, Idlewild’s Black Eden, Oklahoma’s Boley, Murray’s Dude Ranch in California. “The Jewel of the Delta, Mound Bayou, and nearby Po’Monkey’s Juke Joint. Nicodemus and Empire and the McGruder Homestead, and all the thousands of Exodusters. These beacons shine brighter, having been born in the darkness of oppression.

©Rich Frishman, from GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION, THE ECHO THEATRE; Laurens, South Carolina KKK Grand Dragon John Howard opened The Redneck Shop and Klan Museum in the lobby of an old segregated movie theatre in downtown Laurens, South Carolina, in 1996. The store sold KKK, neo-Nazi and white supremacist paraphernalia, like lynching photos, pins, T-shirts, hats, and tactical knives with engraved Ku Klux Klan blades. The auditorium was converted into a meeting hall for the KKK, Aryan Nations, and the American Nazi Party. However, Howard’s partner in the venture, Michael Burden, had a profound change of heart and decided to reform his life. Inspired by his girlfriend, Burden left the Klan and gave the building’s deed to a local Black minister, Dr. David Kennedy, and his church, the New Beginnings Missionary Baptist Church. There was one contingency: Howard would be allowed to continue to occupy the space rent-free until Howard’s death. In 2012 the shop closed, and the building became the church’s property. It is now being renovated as a diversity and reconciliation center by the non-profit Echo Project.

Brenda came to my rescue a month in. I was finishing up in Atlanta, which still calls for more attention, and I was about to continue down the eastern seaboard. Just down the road lay Ahmaud Arbery’s murder site, and Trayvon Martin’s, and the Suwanee River and Willie James Howard. These places filled me with anxiety. I feared failing to adequately represent the burning tragedies contained in each place. I was afraid of the evil powers that might remain. Brenda’s presence stabilized and encouraged me.

As I looked ahead, what hung most heavily over me was another largely forgotten incident of brutality, the single bloodiest day in modern American political history: the Ocoee Massacre. Hundreds of Black residents, a third of the town, were either killed or fled for their lives on November 8, 1920 because a few Black American citizens had tried to exercise their right to vote. Ocoee became an all-white “sundown” town for the next 60 years.

©Rich Frishman, from GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION, EDMUND PETTUS BRIDGE; Selma AL The Edmund Pettus Bridge was the site of the brutal Bloody Sunday beatings of civil rights marchers during the first march for voting rights on March 7, 1965, almost exactly 100 years after the end of the Civil War. Despite the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act months before, the population of Selma and surrounding Dallas County was over 50% African American. Yet, only 2% had been allowed to register to vote. On “Bloody Sunday,” March 7, 1965, over 600 civil rights marchers headed east from Selma on U.S. Route 80 toward Alabama’s capitol, Montgomery, more than 50 miles away. They only made it six blocks. At the Edmund Pettus Bridge, state and local police attacked them with billy clubs, tear gas and whips, driving them back into Selma. Thanks to television and the press, the attacks were seen nationwide, prompting public support for civil rights activists and the voting rights campaign. The bridge is named after Edmund Winston Pettus, a former Confederate brigadier general, Democratic U.S. Senator, and grand wizard of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan.

After a week of failing to make the compelling photograph this resonant crime demanded, we drove on toward our next destination. With a finite amount of time and a near-infinite number of places to honor, these oppositional realities weighed on me. But after driving 100 miles and accomplishing my mission in Tampa, I could not let go of the victims in Ocoee. We turned back.

A few more days of legwork, the guidance of an angel named Kristin Congdon, and a leap of faith led me to the Ocoee Christian Church on Sunday morning. It was in that church, on the very pews we all sat upon, that Black neighbors fearing for their lives were given sanctuary by an all-white congregation.

The screaming mob outside threatened to torch the church, just as they had all the town’s Black churches. As they fired shotguns, puncturing the golden cross atop the steeple, the innocents huddled inside and prayed together. 100 years later, after service, the minister and parishioners listened to my jumbled explanation of why a stranger was in their midst. With grace and kindness, one of them retrieved an artifact of evidence for me to photograph: the long-replaced, bullet-pocked cross.

©Rich Frishman, from GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION, MURDER SITE OF EMMETT TILL; Drew, Mississippi The 14-year-old had been coached on how to behave in the South. It was different than in Chicago, his home. His family came from the Delta during the “Great Migration,” which was a place of many rules for Black people: • Never look a White person in the eye, especially a woman. • Always say “Yes, M’am” or “No, sir.” • Step aside for them. • Never touch a White person. • Be invisible. That last one was the hardest part. In August 1955, Emmett Till, visiting his extended family, walked into Bryant’s General Store in Money, Mississippi, with his cousins, innocently whistling to control his stutter. The young white woman tending the store, Carolyn Bryant, told her husband that Emmett Till had whistled at her and made flirtatious advances. After midnight several nights later, Bryant’s husband Roy and his half-brother J.W. Milam drove out Dark Fear Road to Till’s great-uncle Mose Wright’s house and kidnapped Emmett at gunpoint. The drive to Leslie Milam’s seed barn off Drew-Ruleville Road took about 45 minutes, but the torture had already begun. By the time they reached their destination, several more men had joined. The beatings began in earnest when Emmett was strung up from the barn’s central rafter. After torture and mutilation, they shot him in the head and threw his body into the muddy brown waters of Black Bayou, a 75-pound cotton gin fan tied to his neck with barbed wire. Three days later, a teenager fishing in the Tallahatchie River discovered Till’s brutally beaten body floating in the river.

By mid-March we had reached New Orleans, where our son Gabe would join me and Brenda would depart. Rarely had I ever attempted location work with family. The potential for distraction is just too great. When I’m on an extended photographic road trip, I prefer to be rigorously focused. I rarely even listen to music; I think and meditate and imagine, listening for the quiet guidance that comes from within. Brenda tolerated silence better than our son. Brenda tolerated me far better than did our son. At the outset of this transition, my concern about burn-out was nothing compared to my fear of an explosion.

From NOLA, the plan was to first ascend the Mississippi Delta. One of the most anticipated and dreaded scenes was coming up: the barn in which Emmett Till had been tortured and murdered. Finding the exact location and getting permission from the new owner had taken four years. Emmett’s horrific lynching was a key catalyst in coalescing the modern Civil Rights movement. Honoring his brutally short life was immensely important. Having a capable, concerned, and energetic assistant was a necessity.

We arrived on the afternoon of March 26 to pay our respects, to study the scene, and plan our approach. We began photographing that evening. The picture needed to be shot at night. The horrors experienced by Emmett all took place at night, beginning with Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam kidnapping him at gunpoint from his great-uncle Moses Wright’s home on Dark Fear Road, to his desecrated body being tied to a cotton gin fan with barbed wire and dumped into Black Bayou.

©Rich Frishman, from GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION, FINGERPRINTS OF ENSLAVED WORKER; Oxford, Mississippi Slave labor built much of America, including at the University of Mississippi. If one looks carefully, the fingerprints of slaves can be seen imprinted upon handmade bricks on the Oxford campus, silent testimony to life, rather like fossils in rock. Shown are finger marks at the Croft Institute for International Studies, one of 7 antebellum buildings on campus in Oxford. While many of the bespoke bricks bear the mark of these unnamed craftsmen, most such fingerprints were turned inward so that they are hidden.

Our first night’s effort captured some of the evidence, but we returned the next evening to delve deeper and refine our lighting. The following night we worked again, until we completed the task. Gabe was covered in sweat and dirt and cobwebs, having spent three nights crawling and climbing in the dim light of the single incandescent bulb hanging on a wire. He had been moving about, helping me paint the scene with a small flash.

Along with moral and physical support, Gabe also gave advice. Most I did not want to hear, let alone accept. But he is a smart cookie. Many of his suggestions were valuable ideas, and I would reluctantly need to humble myself to accept his ideas. This began in Natchez, when he read in the New York Times about a municipality gerrymandering an affluent East Baton Rouge school district within a more mixed-income existing district. Photographing that required a 200-mile U-turn, the first of many.

Gabe’s continuing research led us to a remote, abandoned Alabama church with a haunting “slave gallery” that cried out for documentation before disappearance. He also used his conversational skills to run interference for me in Memphis, St Louis, Tulsa, and Tucumcari. As we made it to the West Coast, Gabe invested days trying to convince me to photograph Dodger Stadium in LA, once the site of Chavez Ravine. It had once been home to thousands of people of color. The residents were promised better living conditions and housing, only to be displaced for a Brooklyn team’s new home. I acquiesced just to stop our yelling. But it was a great idea.

We finally pulled back into the driveway on May 16, 2022, over 24,000 miles and 283 days since first departing. Editing, image assembly and postproduction would require another year. The first books from Macmillan arrived at our front door on Gabe’s 30th Birthday, January 19, 2024. What a wonderful gift!

©Rich Frishman, from GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION, U.S. DISTRICT COURT JUDGES CHAMBER; Topeka, Kansas In August of 1951, a special three-judge panel of the US District Court for the District of Kansas in Topeka gathered in these chambers to adjudicate the case of Brown v. Topeka Board of Education. The court held that “no willful, intentional or substantial discrimination” existed in Topeka’s public schools and unanimously found in favor of the Topeka Board of Education’s segregation policy. They were relying upon the doctrine of “separate but equal” set forth by the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision in 1896. The Supreme Court reversed the lower court in May 1954, issuing a unanimous 9–0 decision in favor of the Browns. The NAACP had chosen the family as a proxy for other litigants that had filed numerous similar lawsuits in multiple states. The Court ruled that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal”, and violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The Browns were represented by NAACP chief counsel Thurgood Marshall.

Ghosts of Segregation documents vestiges of racism, oppression, and segregation in America, hidden in plain sight behind a veil of banality. The benches gathered beneath a shade tree in Notasulga, Alabama; we assume this is a place to rest in a park-like setting. We see the small side window at Edd’s Drive-In and think that it’s just a convenient drive-up. The locked black double door on the side of Seattle’s Moore Theatre seems to be a service entrance. The mundane appearance of each scene is reinforced by our assumptions and expectations. In fact, that double door was once the “colored entrance” to the theatre’s second balcony. Edd’s side window was the Jim Crow “colored window,” now used for ventilation. The shaded benches in Notasulga are where Black men sat to have their blood drawn for the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

When I began this project, it was entirely photographic. My intention was for the prints to be displayed in museums and galleries, libraries, and universities. As the collection grew, it seemed that it needed to be a book, which could be easily studied and broadly shared. And it was clear that my lone voice, a white photographer’s voice, could not do justice to the complex story of racism in America.

©Rich Frishman, from GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION, THE LYNCHING OF JOEL WOODSON; Green River, Wyoming Joel Woodson, a Black man, came to Green River in early September 1918, seeking a job to support his wife and family back in Omaha., Nebraska. He began working as a janitor at the Union Pacific Railroad’s social hall. By December, he was frustrated by the racial prejudice he suffered in Wyoming. It was no better than Nebraska. On Tuesday morning, December 10, Woodson took a seat at the depot’s lunch counter and ordered sausage. The waitress refused to serve him what he had requested, bringing him corn mush instead. When Woodson complained, the waitress threw three salt shakers at him, and two White railroad switchmen, Ed Miller and E.J. Curtis slapped him and pushed him out the door. Woodson went to his nearby room, retrieved his pistol, and returned to the restaurant, telling the two White men never to lay a hand on him again. A scuffle broke out, and Woodson fired his gun, hitting Miller twice in the chest and killing him. Curtis was shot in the wrist. Woodson fled the depot and hid in a nearby garage, but he was soon arrested and booked into Sweetwater County jail. Officers hid Woodson in a coal bin when an angry mob of over 500 men gathered outside the jail. This attempt to protect him failed. The crowd stormed the prison, found Woodson, and dragged him to the depot, where he was promptly hanged from a telegraph pole.

Dr. B. Brian Foster, a brilliant young sociology professor and gifted essayist then at the University of Mississippi, generously but tentatively agreed to lend his mind and heart and voice to the project. I had read his book, “I Don’t Like the Blues,” which reflected his shared sense of history and place being intertwined. His writings wove a tapestry of prose and poetry and scientific insights that illuminated hidden aspects of life in Clarksdale, Mississippi. I knew he could bring important depth and authenticity to Ghosts project. He knew I needed a Black man, and told me just that. Reducing the offer to this transactional aspect left me feeling very uncomfortable, but I could not deny this truth. Brian had seen a catalog of my project images, and he was impressed, but we needed to determine how well our creative chemistry extended beyond the diversity of skin color.

In May of 2021, I traveled to Oxford to meet with Brian. He arranged a weekend drive to Clarksdale, where he had spent two years researching and writing his doctoral dissertation, which became his first book. I had photographed Clarksdale a couple of times already, and thought I knew it well.

©Rich Frishman, from GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION, MOORE THEATRE COLORED ENTRANCE; Seattle, Washington Segregated theatre entrances for people of Color were not limited to the states of the former Confederacy. The Moore Theatre is Seattle’s oldest entertainment venue, having opened in December 1907. While much of its architecture was innovative, it maintained the painful tradition of forcing all non-Whites to enter through a side door and slog up several steep flights of stairs to the completely isolated second balcony. Few people strolling past this enigmatic doorway in downtown Seattle realize that it is a vestige of Jim Crow segregation.

Being with Brian opened my eyes to so much that I had missed. And we enjoyed each other. Though I’m his father’s age, and he is my son’s age, and I grew up in a middle-class suburb of Chicago, while he grew up in rural Mississippi as the child of bootstrapping parents and sharecropping grandparents, we shared a great curiosity about the dynamics of race and place and history. We enjoyed each other. Our collaboration began.

From the beginning, Brian helped me see new destinations I needed to explore, he illuminated aspects of Black history that I had completely missed or misunderstood. Though I had thought my thorough research and heartful compassion would allow me to tell this story, I was naive. Brian and his essays, his powerful and poignant insights and anecdotes, are what brings everything together to bear witness to the ghosts that continue to haunt us.

History surrounds us, wherever we look, but we rarely notice it. Seeing the traces requires effort, curi¬osity, and patience. All human landscape has cultural meaning. Because we rarely consider our construc¬tions as evidence of our priorities, beliefs, and behav¬iors, our landscape’s testimony is more honest than anything we might intentionally present. Our built environment is society’s autobiography writ large.

©Rich Frishman, from GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION, As terrified Black residents huddled within the sanctuary on these very benches, the Crucifix that stood atop the Ocoee Christian Church was pockmarked by shotgun pellets fired by the mob of White neighbors intent on voter intimidation.

Many of the locations documented in the book have already disappeared. The “colored” window at Edd’s Drive-in was covered over during a 2022 remodel. The brick mural for Clark’s Café in Huntington, Oregon, which trumpeted “All White Help,” was demol¬ished one week after I photographed it. The College Hill Presbyterian Church in Oxford was destroyed in a 2022 fire. The photographs in this book seek to preserve the evidence of our nation’s sins. When these telling traces are erased, the lessons they contain are easily denied and forgotten. Partic¬ularly by those who seek to deny and forget. Past is prologue. – Richard Frishman

©Rich Frishman, from GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION, WALL AND WATER STREETS Site of the New York City Slave Market New York City, New York On December 14, 1711, the New York City Common Council made Wall Street the city’s first official slave market. Stretching from Pearl to Water, the street was punctuated with merchants selling and renting enslaved Africans and Native Americans. In 1711, New York was rapidly growing, and the expanding needs of the city were often supplied by slave labor. Over 6,000 residents lived in New York; one out of six was Black, and at least 40 percent of the White households included a slave. The market operated until 1762, and New York City remained a key center for the slave trade through the 1850s, but its legacy has been buried so deep that most people don’t even know it existed.

Richard Frishman’s photographs explore how the built environment reveals our cultural histories. In 2021 Frishman was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for photography. His current documentary project, Ghosts of Segregation, explores the vestiges of racial oppression in the landscape of the United States.

Frishman’s photography is included in a wide range collections, including the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, the New Orleans Museum of Art, the Museum of Contemporary Photography, and the OAS Art Museum of the Americas. His work has garnered numerous awards, including the 2019 Review Santa Fe Curator’s Choice Award (juror: Makeda Best), the 2019 PhotoNOLA Portfolio Award, two Sony World Photography Awards (2018), a Communication Arts Photography Award (2018), and a Photo District News Photo Annual Award (2018). In 1983, he was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in feature photography. Frishman lectures around the United States about the intersection of the designed environment, history, and social issues.

Follow Richard Frishman on Instagram: @richfrishman

B. Brian Foster PhD is a writer, storyteller, and sociologist from Shannon, Mississippi. He earned his Ph.D. in sociology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and currently works as Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Virginia. His award-winning book I Don’t Like the Blues: Race, Place, and the Backbeat of Black Life chronicles Black community life and blues tourism in Clarksdale, Mississippi. Brian has also directed two award-winning short films and written for Bitter Southerner, CNN, Delish.com, Esquire, the Ford Foundation, Veranda magazine, and the Washington Post, among others.

To Purchase:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/1250831687?tag=macmillan-20

https://www.powells.com/book/ghosts-of-segregation-9781250831682?partnerid=33241

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250831682/ghostsofsegregation

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ellen Harasimowicz and Linda Hoffman: In the OrchardDecember 5th, 2025

-

Linda Foard Roberts: LamentNovember 25th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Bootsy Holler: Making ItNovember 9th, 2025