Anastasia Tsayder: ARCADIA

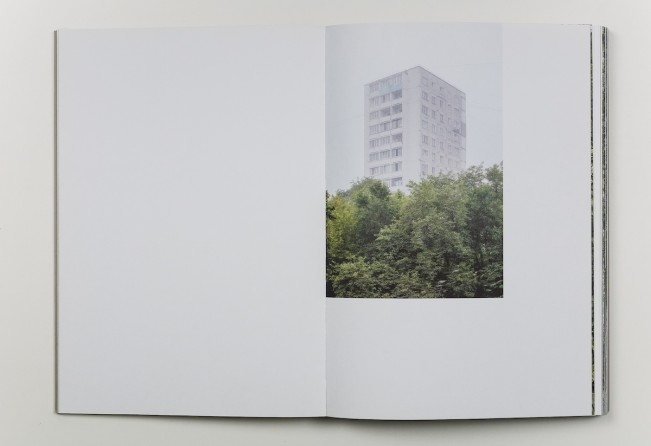

© Anastasia Tsayder, from the series Arcadia

This week on LENSCRATCH guest editor Yana Nosenko brings together the work of four photographers tracing the post-Soviet condition. We are pleased to present a selection of projects and conversations with Anna Guseva, Margo Ovcharenko, Anastasia Tsayder, and Yulia Spiridonova.

Post Co-op

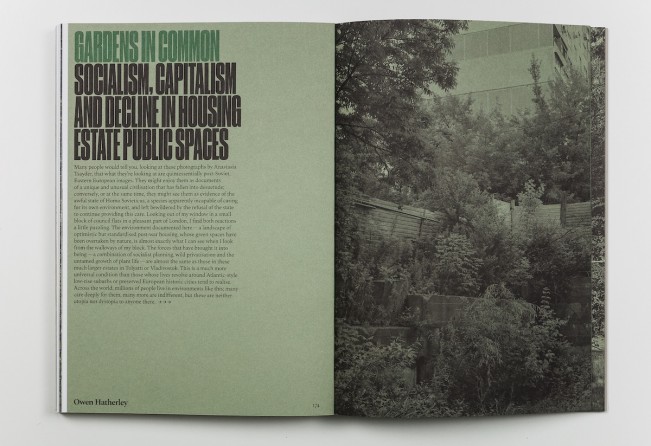

This exhibition brings together four photographic practices that trace the post-Soviet condition as a lived reality shaped by space, fear, discipline, displacement, and the body. Across landscape, portraiture, and long-term documentary work, these artists examine what remains after systems collapse or harden, when “home” becomes unstable and visibility is negotiated rather than guaranteed.

Soviet microdistricts re-emerge as overgrown Arcadias, where vegetation quietly reclaims utopian architecture and transforms control into unpredictability. The psychological aftermath of the 1990s appears as an inherited inner climate, where violence and instability leave lasting marks on identity. In the closed world of women’s football, queer youth find solidarity and refuge within strict boundaries, while the surrounding environment remains hostile. In exile, immigrant communities form fragile “spaces of appearance,” offering temporary belonging while intensifying the tension between survival and assimilation.

Together, these works speak to endurance under unstable conditions: how people adapt, hide, re-root, and continue. Here, “home” is neither guaranteed nor singular. It is overtaken by plants, haunted by memory, protected by rules, searched for in diaspora, and continually reconstructed, one image at a time. — Yana Nosenko

Anastasia Tsayder (1983) is a documentary photographer, visual artist, and curator based in Minsk (Belarus). She works with photography, video, archives, and installations. Her artistic studies focus on the cultural and visual transformations of post-Soviet society.

Follow Anastasia Tsayder on Instagram: @anastasia_tsayder

ARCADIA

The project searches for the pastoral Arcadia within centrally planned Soviet modernist neighbourhoods. Soviet post-war modernism coincided with the global spread of the International Style; here, however, it lasted from the late 1950s through the 1990s, as the planned economy and state-owned land enabled nation-scale construction programs.

Uniformly designed residential areas were built from scratch, including infrastructure, pre-planned green spaces, and parks. Today, urban vegetation has overtaken these environments: trees outgrow neighboring buildings, and cultivated plants exceed their intended boundaries. Plants become both the result and illustration of transformation, while remaining active participants.

Once conceived as a socialist paradise, the utopian garden city has been re-conquered by plants, forming a new romantic landscape of the post-Soviet space. The Soviet Garden City aimed to turn each microdistrict—the basic unit of Soviet urban planning—into a worker’s paradise. The transition from a socialist economy to a free market, and from industrial to post-industrial society, relieved people of responsibility for maintaining these gardens, allowing vegetation to reclaim space.

Left to themselves, plants reflect the economic turmoil while actively reshaping the city. Gradually overtaken microdistricts become “non-places,” offering relief from surveillance and social pressure. Indistinguishable neighborhoods quietly acquire a feral state; endemic plant compositions, climate responses, and natural behaviors restore uniqueness to once-uniform spaces.

As with my other projects, Arcadia explores collective experience shaped by social conditions and nature.

Photographs were made in Russia, Belarus, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, and Abkhazia.

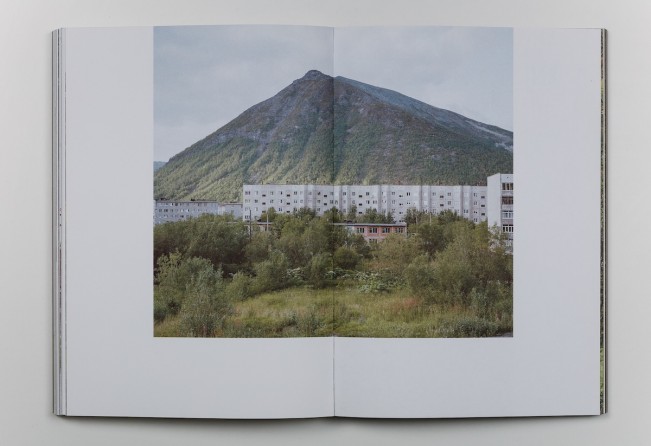

© Anastasia Tsayder, from the series Arcadia

Yana Nosenko: What drew you to the idea of Arcadia in relation to Soviet modernist neighbourhoods? What was the starting point for this project: lived experience, historical inquiry, or observation of the built environment?

Anastasia Tsayder: I spent my childhood in Saint Petersburg, in a mass-produced building with a similarly green courtyard. It was a strangely ambivalent experience: on the one hand, you live in the city, and on the other, there’s a forest just outside your windows—an incredible space to play at, when you are a child. Later or on, as an adult, I noticed that this familiar environment was in fact something very unique to the post-Soviet landscape, as well as a shared experience for so many people across different countries.

YN: How do you understand the Soviet “Garden City” ideal today, was it a genuine social promise, an ideological tool, or both?

AS: I think it was both. Certainly, in a country devastated by the war, such housing, despite its modest conditions, was far superior to the housing that had existed before, and it did give people both a sense of personal space and a promise of a better future. At the same time, it was an important part of the propaganda message—mass construction and free housing became ubiquitous subjects in Soviet cinema and literature. Soviet newspapers published reports on how many square meters were built each year—and these were seen as one of the main markers of the success of the communist system. This kind of propaganda was intended for the domestic market, but also to promote the superiority of the communist system worldwide.

YN: Do you understand the spread of vegetation as a form of reclamation, or as an unfolding of intentions already present in the original design?

Such expansion is more a consequence of social change than a result of the ideas embedded in the original design. Uniform residential areas were designed with all the necessary infrastructure, including large green areas surrounding the buildings. The Soviet garden city was intended to transform each neighborhood—the “microdistrict”— into a working man’s paradise. With the transition from the planned economy to the market economy and from the industrial society to the post-industrial state, urban vegetation was left on its own. Without the centralized supervision and control—as municipal authorities and residents lacked the resources in the new economic reality—it began to take over new spaces.

YN: Do you see these neighbourhoods as failed utopias, transformed utopias, or something else, and how do they reflect, or resist reflecting, the current economic and political climates of the places you photographed?

AS: On the one hand, the trees speak of the collapse of the utopia, and on the other, we see how these new spaces create a sense of a “non-place”—where one can escape the societal pressure, be left one’s own, find a refuge from the commercialized urban environment—creating new utopias, likely very different from those originally planned. The plants and their chaotic growth bear witness to the economic and social changes that occurred in these territories in the 1990s, traces of which are still visible today, and documentary photography is the ideal medium for capturing this. In some places, we see more idyllic urban landscapes, while in others, the degree to which urban spaces are taken over by the vegetation may acquire an eerie beauty, with landscapes reflecting consequences of military conflicts, closed borders, areas depopulated—as with the entrance to Tashkent’s central bus station where the overgrown vegetation becomes the evidence of the cessation of bus service between neighboring countries, or entire areas in the north of Russia that were abandoned by people.

YN: How early in the project did you begin thinking about the book as a final form?

AS: Although the project wasn’t initially conceived exclusively as a book, I feel it as a very suitable way to present it. From the very start, it was clear to me that I wanted to include in it different regions, different countries, and examine how different climates, landscapes, and degrees of social change influenced the environment. Even though the architecture of the buildings may be similar in Riga and Bishkek, the landscape in each case is unique.

© Anastasia Tsayder, from the series Arcadia

YN: Having photographed across many cities and countries, what similarities or differences surprised you most, and did any images or places take on new meanings once they were sequenced together in the book?

AS: I was making the book together with the wonderful Latvian team at TALKA Publishing House, and, from the start, it was our decision that we were interested in the social aspect of these landscapes, on the one hand, and the collective visual experience that united residents of post-Soviet cities, on the other. We conceived the book as a 10,000-kilometer journey (the approximate distance separating the westernmost from the easternmost points in the project) through a garden that had turned into a forest. This determined the sequence of the images and the absence of captions—so it is up to the reader’s imagination to determine which city they are in at any particular moment.

YN: Why do you think Arcadia resonates now, and what questions has it opened up that you are continuing to explore in your current work?

AS: For me, “ARCADIA” is also, in a sad way, a story about the collapse of faith in the ideas of the modernist era that this architecture once proclaimed (but didn’t necessarily live up to)—the aspirations for social equality, affordable housing, and the building of a future based on humanistic values. It seems that these ideas remain no less relevant—or perhaps, their relevance has only increased. In my current artistic practice, I continue to explore the post-Soviet landscape and how photography can convey complex social and economic connections. I believe that the landscape still contains many in-evident and yet unrevealed meanings.

Yana Nosenko is a multidisciplinary artist and curator whose work explores themes of immigration, displacement, nomadism, and familial separation — drawing from her own experiences and expressed primarily through lens-based media.

She has exhibited at the International Center of Photography Museum, Gala Art Center, MassArt x SoWa, and Abigail Ogilvy Gallery. In 2023, she was awarded a residency at The Studios at MASS MoCA. That same year, she joined the Griffin Museum of Photography as a Curatorial Associate and Exhibition Designer, where she helped co-curate and organize exhibitions, oversaw daily operations, facilitated artist talks and panels, designed marketing materials, and worked closely with visitors and artists. In 2025, Yana was appointed Director of Education and Programming at the Griffin Museum, where she continues to foster artistic dialogue and learning through exhibitions, public programs, and community engagement.

Before focusing on photography, Yana studied graphic design at the Stroganov Moscow Academy of Design and Applied Arts and worked as a graphic designer at Strelka KB, an urban planning firm in Moscow. In 2017, she completed a major independent project: the design of Mayak, a typeface inspired by Soviet Constructivist fonts of the 1920s–30s, later released by ParaType.

She holds an MFA in Photography from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and a certificate from the International Center of Photography.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anastasia Tsayder: ARCADIAJanuary 28th, 2026

-

Ed Kashi: A Period in Time, 1977 – 2022January 25th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Kevin Cooley: In The Gardens of EatonJanuary 8th, 2026

-

William Karl Valentine: The Eaton FireJanuary 7th, 2026