Yulia Spiridonova: Wayward Son

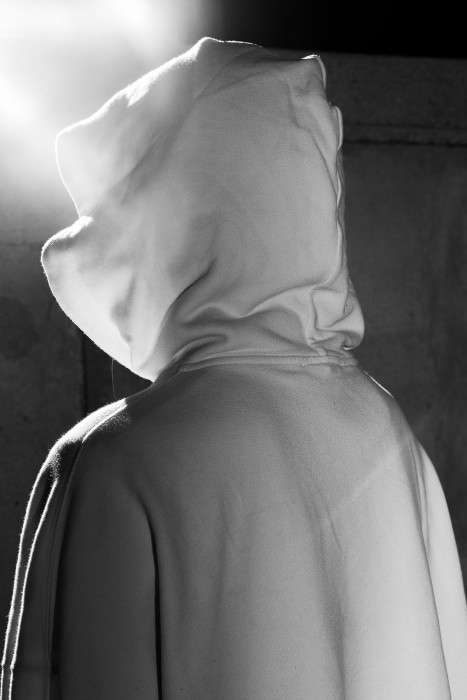

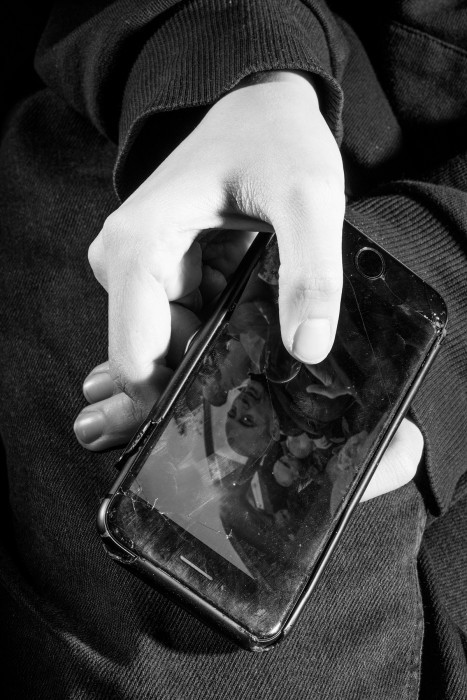

© Yulia Spiridonova from the series, Wayward Son

This week on LENSCRATCH guest editor Yana Nosenko brings together the work of four photographers tracing the post-Soviet condition. We are pleased to present a selection of projects and conversations with Anna Guseva, Margo Ovcharenko, Anastasia Tsayder, and Yulia Spiridonova.

Post Co-op

This exhibition brings together four photographic practices that trace the post-Soviet condition as a lived reality shaped by space, fear, discipline, displacement, and the body. Across landscape, portraiture, and long-term documentary work, these artists examine what remains after systems collapse or harden, when “home” becomes unstable and visibility is negotiated rather than guaranteed.

Soviet microdistricts re-emerge as overgrown Arcadias, where vegetation quietly reclaims utopian architecture and transforms control into unpredictability. The psychological aftermath of the 1990s appears as an inherited inner climate, where violence and instability leave lasting marks on identity. In the closed world of women’s football, queer youth find solidarity and refuge within strict boundaries, while the surrounding environment remains hostile. In exile, immigrant communities form fragile “spaces of appearance,” offering temporary belonging while intensifying the tension between survival and assimilation.

Together, these works speak to endurance under unstable conditions: how people adapt, hide, re-root, and continue. Here, “home” is neither guaranteed nor singular. It is overtaken by plants, haunted by memory, protected by rules, searched for in diaspora, and continually reconstructed, one image at a time. — Yana Nosenko

Yulia Spiridonova is a multimedia, lens-based artist working across photography, collage, and installation. With over a decade of experience as a photo editor and editorial photographer, she has collaborated with clients such as PORT Magazine, Esquire Russia, RBC Magazine, and L’Officiel. Her work has been exhibited internationally and featured in publications including Dazed Digital, The Calvert Journal, PhMuseum, LensCulture, A New Nothing, and others. Yulia holds a Post-Baccalaureate Certificate and an MFA in Photography from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. She is the recipient of the Anderson Ranch MassArt Fellowship (2023), the Abelardo Morell MassArt Photography Thesis Prize (2024), the MASS MoCA Studios MassArt Fellowship (2024), and the MassArt Postgraduate Fellowship (2025). She is currently based in Boston, Massachusetts, where she works as a Teaching Assistant in Harvard University’s Department of Art, Film, and Visual Studies and teaches multiple courses as adjunct faculty at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design.

© Yulia Spiridonova from the series, Wayward Son

Wayward Son

Wayward Son examines contemporary post-Soviet displacement through the intimate social landscapes formed by those who left their home countries under authoritarian pressure and the gradual erosion of civic life. The individuals who appear in this work – Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Georgians, Armenians, among others – have been propelled into movement not by aspiration but by necessity.

Hannah Arendt describes the space of appearances as something that does not exist in advance. It comes into being whenever people gather, speak, and act in the presence of one another – and disappears as soon as they disperse. Wayward Son dissects one of these precarious spaces, allowing the viewer to absorb into the world of immigrants whose lives are shaped by displacement, unfamiliarity, and the exigent necessity to adjust socially, geographically and culturally.

The aftermath of exile produces a nonlinear existence in which legal vulnerability, shifting visa conditions, language barriers, and family separation render the future provisional. Wayward Son operates in the historical shadow of earlier expulsions – most famously the Philosophers’ Ship of 1922. While departures today unfold under a new set of geopolitical conditions, the timeless practice of immigration perseveres ubiquitously and remains relevant.

The photographs in Wayward Son, made in Massachusetts and Florida, observe immigrant Russian-speaking communities in micro-detail, encapsulating the space of appearances as a nostalgia haven wherein timelines are fractured. Many of these encounters originate in anonymous digital channels – primarily Telegram groups – where newcomers search for housing, legal advice, emotional solidarity, or simply the comfort of a familiar language. The cultural unity of this space allows an ephemeral escape from unwanted reality, yet its evanescence prolongs intense emotional tension with the “real world”. The space of appearances artificially satisfies the inherent human desire to be seen, thereby keeping figures sane, but submits them to the unfeasibility of proper assimilation. At the same time, the work recognizes the courage required to inhabit life under displacement and persist in spite of all odds. By attending to this dichotomy, Wayward Son captures feelings of celebration and contemporaneous melancholy, apprehending the figures’ infinitely complex world.

Ultimately, Wayward Son views displacement as the slow work of re-rooting after being pulled from the ground. People don’t grow back in neat lines or predictable forms. They take hold where the soil is loose enough to let them breathe – and hide where the sun is too bright to survive. The work holds this image while simultaneously pressing against it and entertaining doubts – must adaptation require concealment? Is it ever possible to adjust to a new sun without burning – to outlive predestined familiar habits in an increasingly demanding world?

Yana Nosenko: At the outset, what were you hoping to understand or test through Wayward Son, and how did those intentions shift once the work began?

Yulia Spiridonova: Photographic communities—whether defined by nationality, culture, religion, or shared identity—have long served as a familiar framework within contemporary photographic practice. The genre is both legible and compelling, offering a structured way to explore belonging and collective experience. Over time, however, I became increasingly interested in the possibility of documenting a community that is not tightly connected, but instead held together by displacement, circumstance, and shared emotional conditions.

During my earlier stays in the United States, I consciously avoided Russian circles, distancing myself as much as possible from my national identity and, in many ways, rejecting it altogether. This return unfolded differently. Moving to the U.S. alone, I experienced a profound sense of isolation. About six months after arriving in Boston, I created a Spotify playlist titled “Longing for Home.” That initial feeling of homesickness became the emotional point of departure for this project. I wanted to understand what I might still recognize or resonate with in the culture I had left behind. I found myself suspended between memories of something genuinely good from my past and a strong desire to resist a culture I felt deeply disappointed by. That tension formed the foundation of the project.

I approached the work in an almost anthropological manner, observing how other Russian-speaking immigrants around me lived, how they formed relationships, and how they navigated unfamiliar social and spatial contexts. At its core, the project emerged from curiosity—a desire to see who constituted this dispersed community and what bound it together beyond nationality.

I began the project without clear expectations, which made what I encountered especially revealing. Most of the people who responded to my messages or group posts were politically and ideologically aligned with my own position. Despite differences in age, profession, and social background, they shared a pervasive sense of instability. As immigrants in a foreign country, many carried anxieties around visibility, legality, and belonging. They spoke openly about how they arrived, why they left, and what they were forced to abandon—homes, careers, families, and familiar social structures.

This fragile condition of immigrant existence, coupled with the resilience required to endure uncertainty and the courage demanded by the decision to leave, became central to the visual language of the series. It is a state shaped simultaneously by vulnerability and determination, by loss and by the ongoing labor of rebuilding life elsewhere.

© Yulia Spiridonova from the series, Wayward Son

YN: Many encounters began in anonymous Telegram groups. How did working within these digital spaces, and through a shared language, shape your approach to trust, visibility, and consent?

YS: You know how “lost in translation” is a common phrase that points to the difficulty of conveying certain nuances of tone and meaning. As I mention in my artist statement, I photograph not Russians, but Russian-speaking people—including Belarusians, Ukrainians, Georgians, Armenians, and others—deliberately emphasizing that a shared culture (which can be loosely described as post-Soviet for clarity) and a common language immediately create a level of trust and intimacy. This emerges through jokes, casual conversations, and everyday expressions that only make sense within a shared historical and cultural context—something people from post-Soviet spaces understand almost instinctively.

In my view, the hostility imposed on us, and especially the war—which is unquestionably inhumane and a collective tragedy—does not erase the sense of closeness among people now scattered across different continents. Many of these individuals protested against their own totalitarian regimes or against corrupt, oligarchic systems of power. Despite different national backgrounds, they recognize how similar their experiences are—in their displacement, in their search for ways to survive, and in their refusal to accept inhumane conditions, the machinery of propaganda, and poverty.

I find it essential to emphasize this unity among people who, for different factual reasons but through fundamentally similar circumstances, had the courage to leave and begin again somewhere on unfamiliar ground.

YN: Did you find yourself photographing moments of gathering more than solitude, or did isolation become equally important to the narrative?

YS: I initially began this project mostly with single-person portraits, as they were much easier to arrange logistically. Over time, as I became immersed in this communal way of life and was gradually accepted into different circles, I shifted toward photographing gatherings of people, or individuals situated within group settings. It takes time for people to feel comfortable with someone moving among them with a camera, but once that ease is established, situations open up and emotional exchanges emerge organically. The range of interactions becomes remarkably rich and unpredictable.

When people share lived experience, certain cultural gestures—such as men embracing one another—carry meaning on their own, without the need for direction or heavy staging. At the same time, I continue to move back and forth between these two distinct modes of representation: the intimate single portrait and the collective scene. They complement one another and establish a rhythm within the series, inviting the viewer into spaces and moments that would otherwise remain inaccessible.

YN: The work addresses the desire “to be seen” while also questioning assimilation. How do you negotiate visibility without reinforcing expectations placed on immigrant bodies?

YS: When initial trust is established, I deliberately collaborate with people around the degree to which they wish to be visible. We speak openly about whether they have concerns about facial recognition in the images or if they feel comfortable being fully revealed. I offer a broad prompt, asking how they would like to be perceived, what actions they imagine, or how they envision their posture and presence. There is always an element of unpredictability in these responses. I am particularly interested in learning about their hobbies, as someone who may initially appear reserved often reveals unexpected aspects of their life—dancing every Thursday, practicing judo, or engaging in other activities that reshape how they inhabit the frame. This collaborative process frequently results in the most surprising and, to me, the most compelling photographs.

Another realization emerged when I began positioning myself within the groups I was photographing—especially during my time in Florida. As people grew accustomed to my presence, they gradually stopped acknowledging the camera, even when I used flash at night. Conversations continued, interactions unfolded naturally, and I was able to move freely through the space. This collective ease produced scenes in which the flash transformed everyday reality into something almost theatrical. The light constructs a visual atmosphere that departs from the literal moment while still preserving the agency of those depicted. This experience has increasingly drawn me toward photographing gatherings.

YN: By photographing Russian-speaking communities in Massachusetts and Florida, you introduce distinct social and geographic contexts. How did those differences shape the work, and do you think the project’s message would shift if it were made in a different country?

YS: Do you remember when we once went together to Alexander Nizlobin’s stand-up show in Boston, and one of his jokes was that back home you choose your friends, but in emigration you become friends with whoever happens to be around? I feel that this comment relates closely to the project. When I photograph Russian-speaking people, it seems to me that the group I encounter—whether in the United States or what I see online in Europe and Asia—is quite similar. Of course, if I were photographing in other states or countries, things might look somewhat different, but I work with the people available to me, and I believe they represent the immigrant community now scattered across different continents.

Many of the people who appear in the photographs have moved frequently, lived in different states, and continue to relocate; their current place of residence is not something fixed or permanent, but rather one stage within a nomadic lifestyle in which they constantly navigate where to live and what to do next.

After 2022, there are certain defining characteristics that unite us. We were forced to leave a country where we had homes, jobs, friends, parents, schools for our children, and everything else that structured our lives. Because of political disagreement, we had to abandon all of that, move elsewhere, and start again from scratch. In this sense, I hope the people I photograph represent a new wave of Russian emigration that has unfolded on a particularly large scale following the war in Ukraine and the tightening of the political regime.

YN: You reference the Philosophers’ Ship of 1922. How does that history of exile inform your understanding of contemporary displacement, and do you see “Wayward Son” as documenting a specific moment or a longer continuum of migration?

YS: When I reference the Philosophers’ Ship of 1922, I am speaking about my sense of grief over the repetition of repression and fear experienced during the Soviet period. After the collapse of the USSR, there was a widespread feeling that the country was moving toward democracy—toward political freedom, freedom of speech, and economic growth. In the 2000s, when I participated in protests with Alexei Navalny, who has since died (or, as I believe, was killed), it seemed that this direction was possible. Over time, however, that trajectory collapsed back into a totalitarian system where dissent is no longer tolerated.

This return to authoritarianism feels deeply familiar to anyone who studied Russian history or heard stories from older generations. The repetition of repression forcing out those who think critically and creatively is what makes the parallel with 1922 so painful. Once again, the country is expelling its intellectual and cultural communities.

This became especially personal for me because before leaving Russia I worked as a photo editor at one of the largest media companies in the country. In 2022, it became impossible to report the news without facing danger from authorities while also being accused abroad of complicity with the regime. Many of my colleagues and friends left. I lived in the center of Moscow, in a liberal neighborhood surrounded by educated, engaged people. When they all disappeared, the city I knew disappeared with them.

YN: Because your artist statement ends with doubt rather than resolution, what questions remain unresolved for you, and has working on “Wayward Son” changed how you understand your own relationship to place, belonging, or adaptation?

YS: In the present geopolitical climate—marked by shifting visa regimes and the volatility governing mobility—the future often appears less as a horizon than as a contingency. That condition frames both my own life and those of the people I photograph for the “Wayward Son” series. The project does not simply document individuals; it registers a historical atmosphere in which belonging is provisional.

What the work has clarified for me is that place no longer functions as a stable foundation for those living through repeated relocation. Apartments, cities, and nations become temporary platforms rather than anchors. What sustains people instead is community—the ability to rebuild connection and belonging wherever they arrive. This shared condition becomes a source of collective endurance.

We may be uncertain about the future, but we know we have the resilience to face challenges and to figure out what comes next, even when it remains an open question.

© Yulia Spiridonova, from the series Wayward Son

Yana Nosenko is a multidisciplinary artist and curator whose work explores themes of immigration, displacement, nomadism, and familial separation — drawing from her own experiences and expressed primarily through lens-based media.

She has exhibited at the International Center of Photography Museum, Gala Art Center, MassArt x SoWa, and Abigail Ogilvy Gallery. In 2023, she was awarded a residency at The Studios at MASS MoCA. That same year, she joined the Griffin Museum of Photography as a Curatorial Associate and Exhibition Designer, where she helped co-curate and organize exhibitions, oversaw daily operations, facilitated artist talks and panels, designed marketing materials, and worked closely with visitors and artists. In 2025, Yana was appointed Director of Education and Programming at the Griffin Museum, where she continues to foster artistic dialogue and learning through exhibitions, public programs, and community engagement.

Before focusing on photography, Yana studied graphic design at the Stroganov Moscow Academy of Design and Applied Arts and worked as a graphic designer at Strelka KB, an urban planning firm in Moscow. In 2017, she completed a major independent project: the design of Mayak, a typeface inspired by Soviet Constructivist fonts of the 1920s–30s, later released by ParaType.

She holds an MFA in Photography from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and a certificate from the International Center of Photography.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Yulia Spiridonova: Wayward SonJanuary 29th, 2026

-

Ed Kashi: A Period in Time, 1977 – 2022January 25th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026