Dugan Aguilar: She Sang Me a Goodluck Song

“…If you are unacquainted with the California Indian world, shed all your preconceived notions and give yourself over to a new experience.”

Earlier this year, I took a road trip across the Southwest, traversing numerous Indian Reservations with spectacular vistas. I did a lot of thinking about Native Americans and their difficult legacy within our country’s history and wondered why more photographers were not exploring this sensitive terrain. Happily, Heyday Books has just released She Sang Me a Good Luck Song: The California Indian Photographs of Dugan Aguilar, edited by Theresa Harlan.

Earlier this year, I took a road trip across the Southwest, traversing numerous Indian Reservations with spectacular vistas. I did a lot of thinking about Native Americans and their difficult legacy within our country’s history and wondered why more photographers were not exploring this sensitive terrain. Happily, Heyday Books has just released She Sang Me a Good Luck Song: The California Indian Photographs of Dugan Aguilar, edited by Theresa Harlan.

Dugan Aguilar has exhibited his work close to his Northern California home at places such as the Stewart Indian Museum,Carson City, Nevada; Chaw’se Indian Grinding Rock State Park, Pine Grove, California; and the California State Indian Museum, Sacramento. He has also exhibited his work in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, Santa Fe, New York, and London, and his prints are in the permanent collections of Princeton University, the Southwest Museum of the American Indian, the Autry National Center of the American West, and the British Museum. He was the staff photographer for the California Indian Basketweavers Association for thirty years, the California Indian Storytellers Association, and the National Indian Justice Association.

An exhibition of She Sang Me a Good Luck Song: The California Indian Photographs of Dugan Aguilar will be traveling to Goudi’ni Native American Arts Gallery at California State University, Humboldt Humboldt, CA from October 1 – December 12, 2015 and to Grace Hudson Museum, Ukiah, CA from May 1-July 31, 2016.

Theresa Harlan was inspired by Native artists who create beauty from the intersection of history, culture, and life experience and became an advocate for them through her work as a curator and writer on contemporary Native art and photography. She administered programs for the California Arts Council and directed the Carol Gorman Museum in the Native American Studies Department at UC Davis. Harlan is Kewa (enrolled member of Santa Domingo Pueblo), Jemez Pueblo, and Laguna Pueblo, and is the adopted daughter of Liz Campigli Harlan (Coast Miwok, Tomales Bay) and John Harlan. She lives in Vallejo, California, with her husband, Tiger.

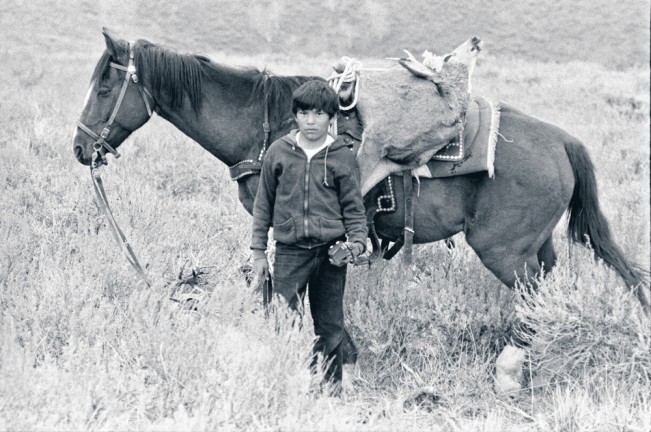

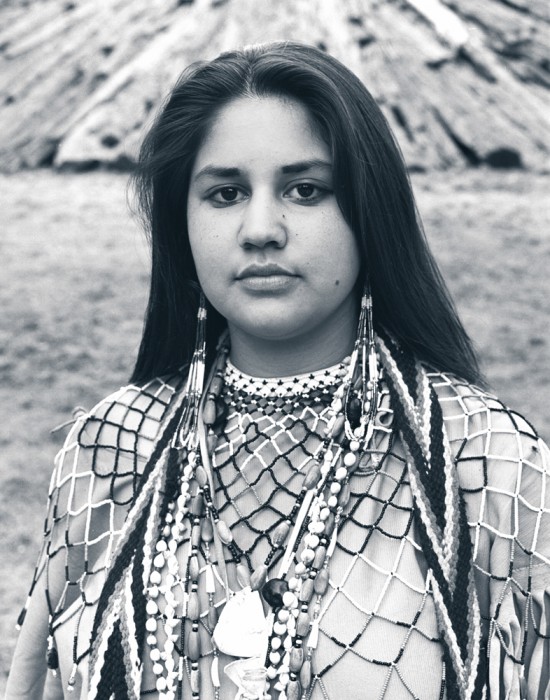

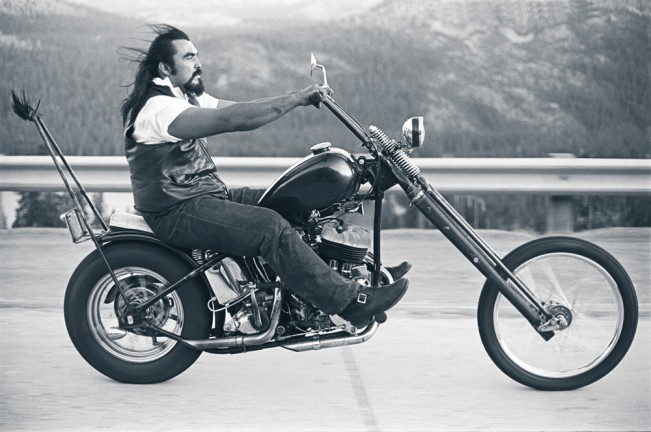

For almost forty years, Dugan Aguilar has picked up his camera and with a gentle manner, traveled across California to photograph gatherings where California Indian people meet. His self-described purpose is to “show Natives alive and well” – a people who, it was predicted, would succumb to mission building, military campaigns, the infamous gold rush, and the development schemes of land speculators. This mythical Native “demise” is reflected in museum exhibitions in which Native people are depicted in the past tense but artworks by living Native American photographers and artists are absent. Dugan’s body of work makes a Native world and existence present and visible.

Dugan will tell you of his love for Native faces, faces distinctly California Indian, yet with a specific tribal lineage. A generation of California Indian people has grown accustomed to seeing themselves, family, and friends in his photographs, displayed in homes and Heyday’s quarterly, News From Native California.

Dugan Aguilar (Maidu/Northern Paiute/Achomawi), a man of few words, speaks his heart through his photography. With nature’s light and a camera, he creates images of indigenous California people, photographs that embody the depth of their subjects’ beauty, strength, and humor. His portraits of people, places, and ceremonies combine the intimacy of family photos with the technical skill of a masterful artist. His photographic works have been exhibited nationally and internationally, and a generation of California Indian people have grown accustomed to seeing his photographs in their homes, museums, and News from Native California.

Aguilar’s photos defy the romanticized and melodramatic images by which Native people are often depicted. Ranging from portraits of military veterans, basket makers, and dancers to meditative landscapes. Aguilar’s work documents—and contributes to—the perseverance and renewal of Native California’s living, vibrant cultures.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Carolyn Monastra: Divergence of BirdsFebruary 2nd, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Yi Wan Gyo: Nirvana-Beyond DarkJanuary 13th, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Han ChungShik: GoyoJanuary 12th, 2026