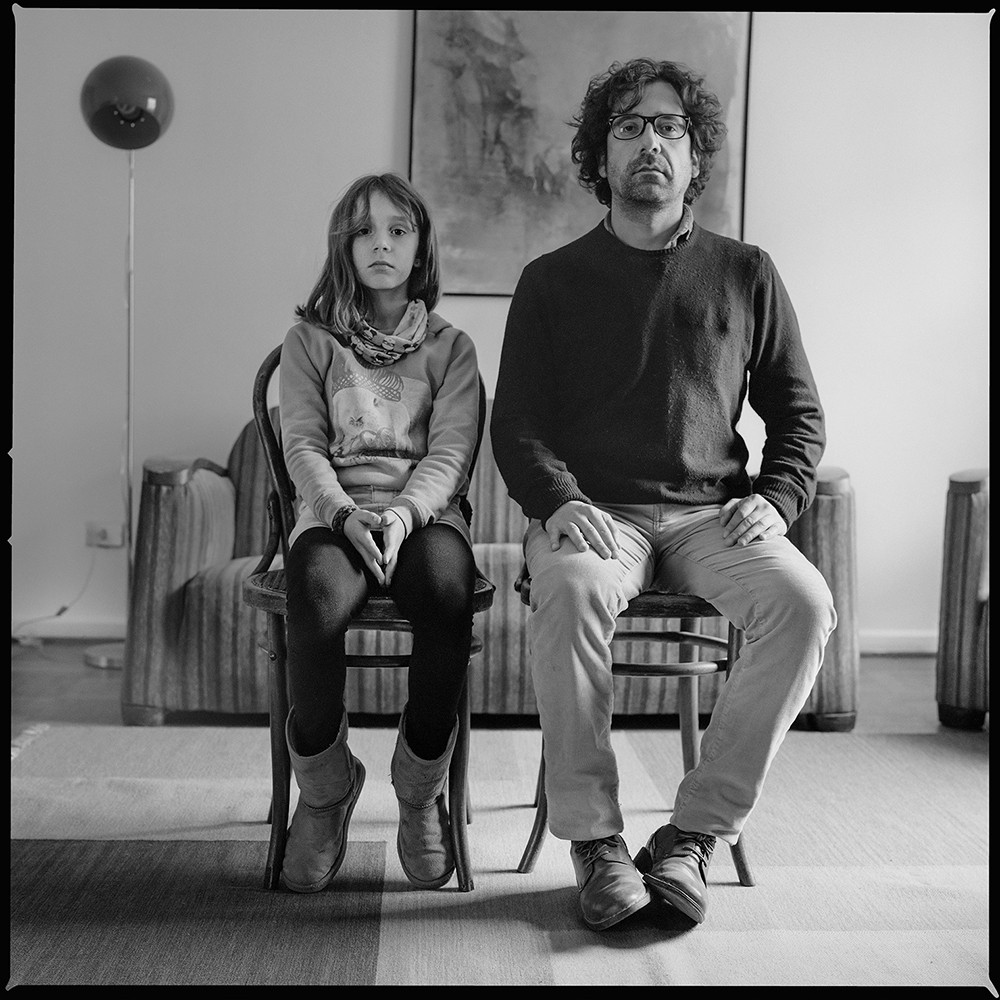

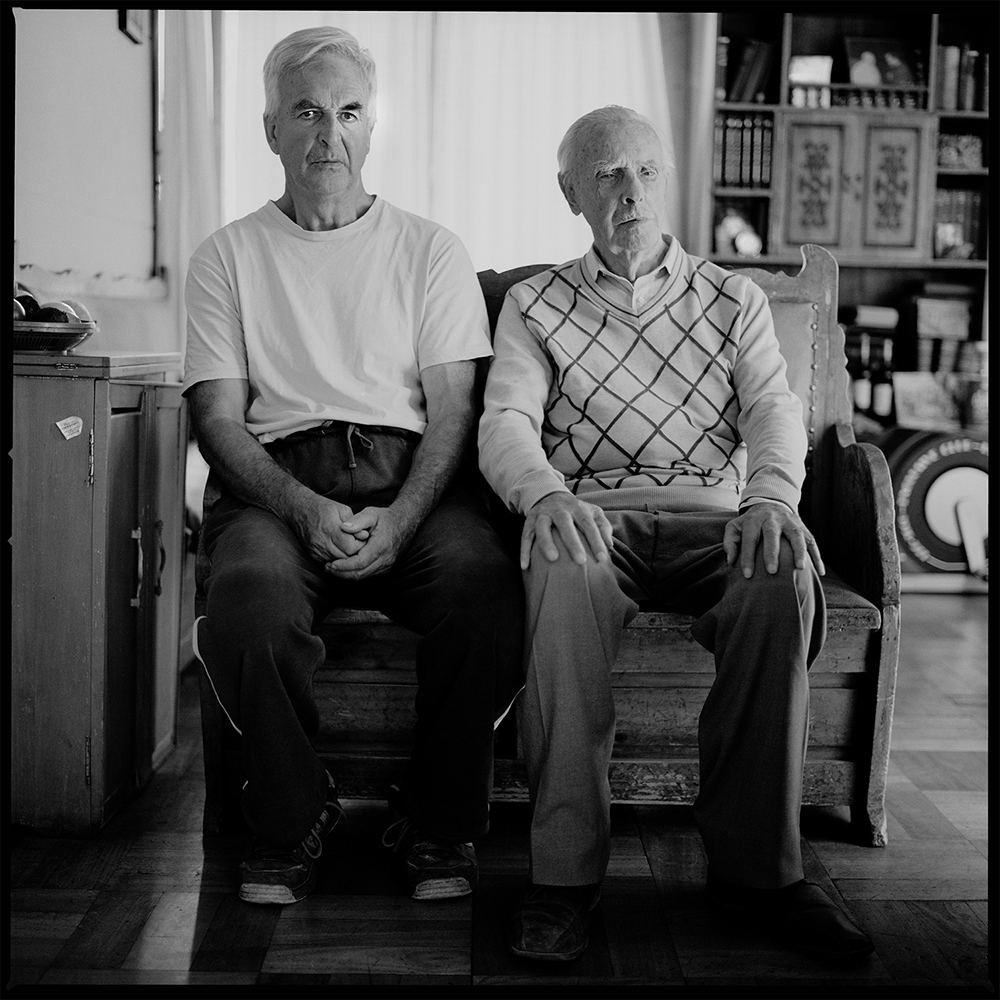

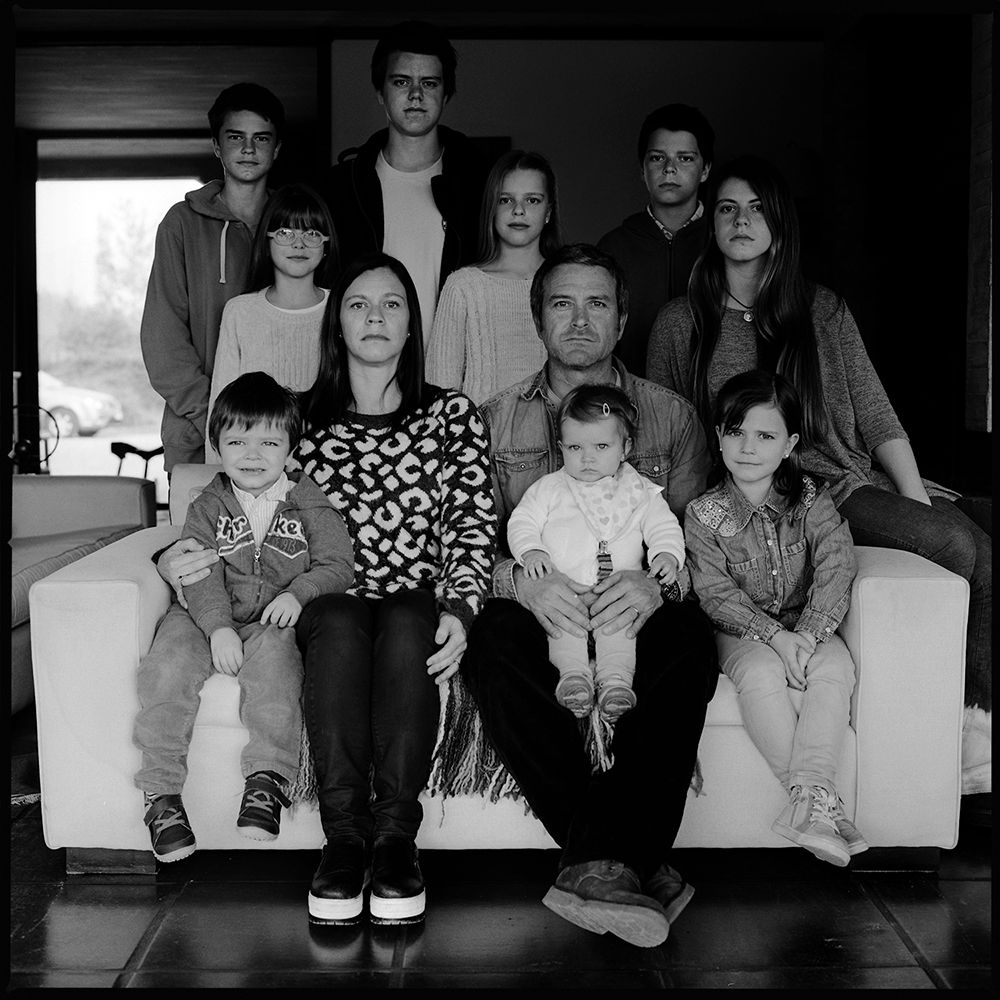

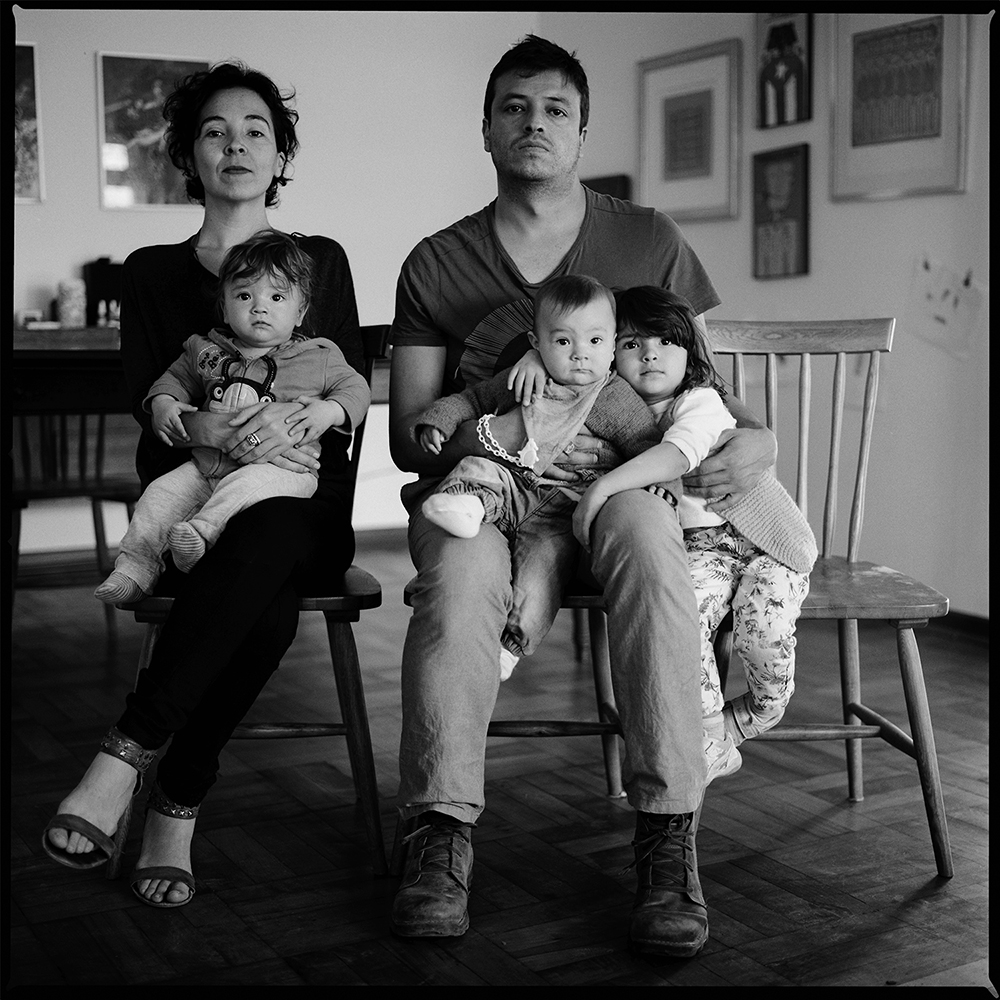

Guillermo González: Domestic

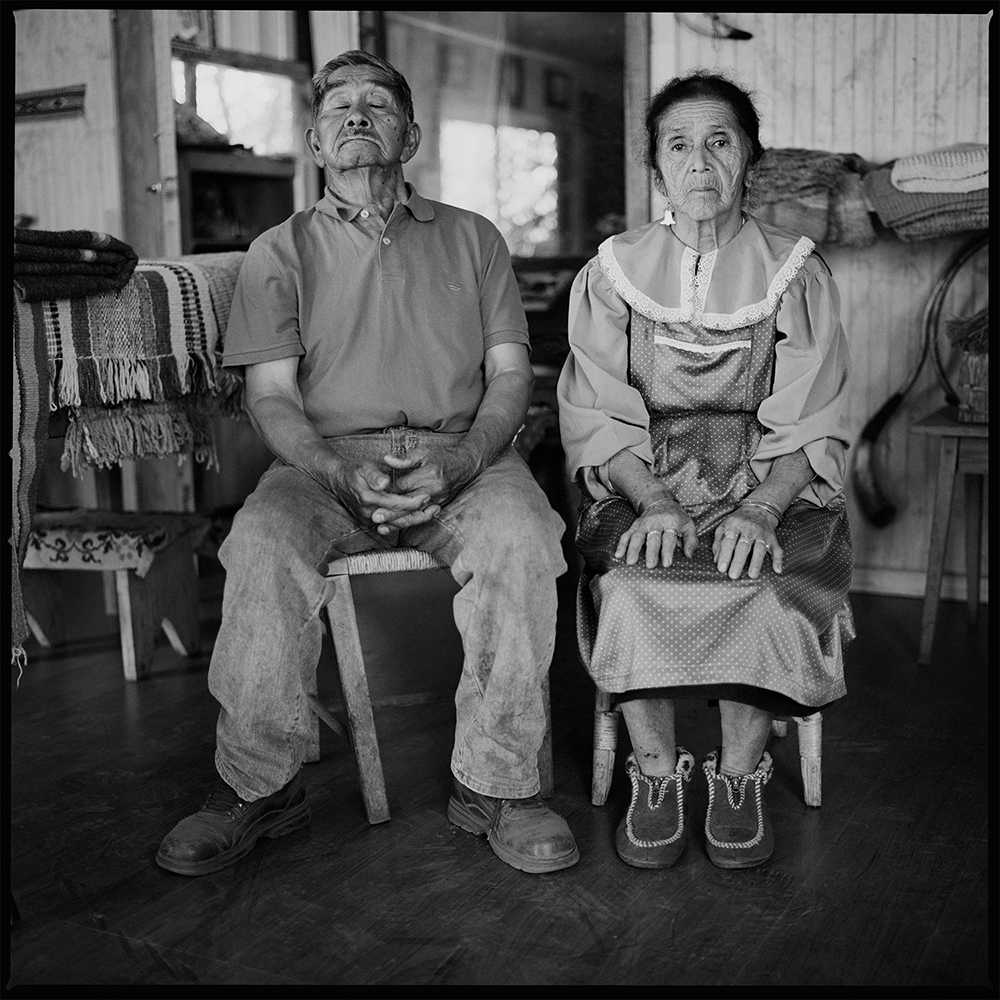

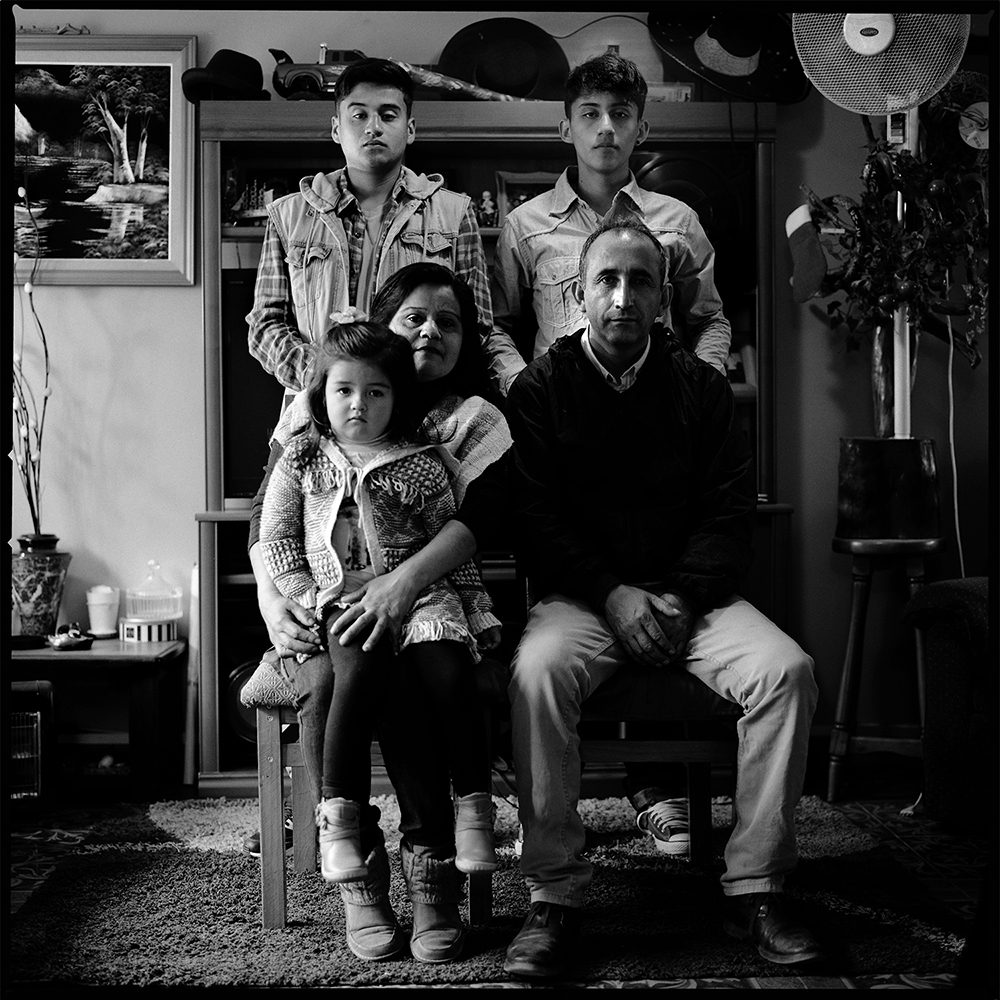

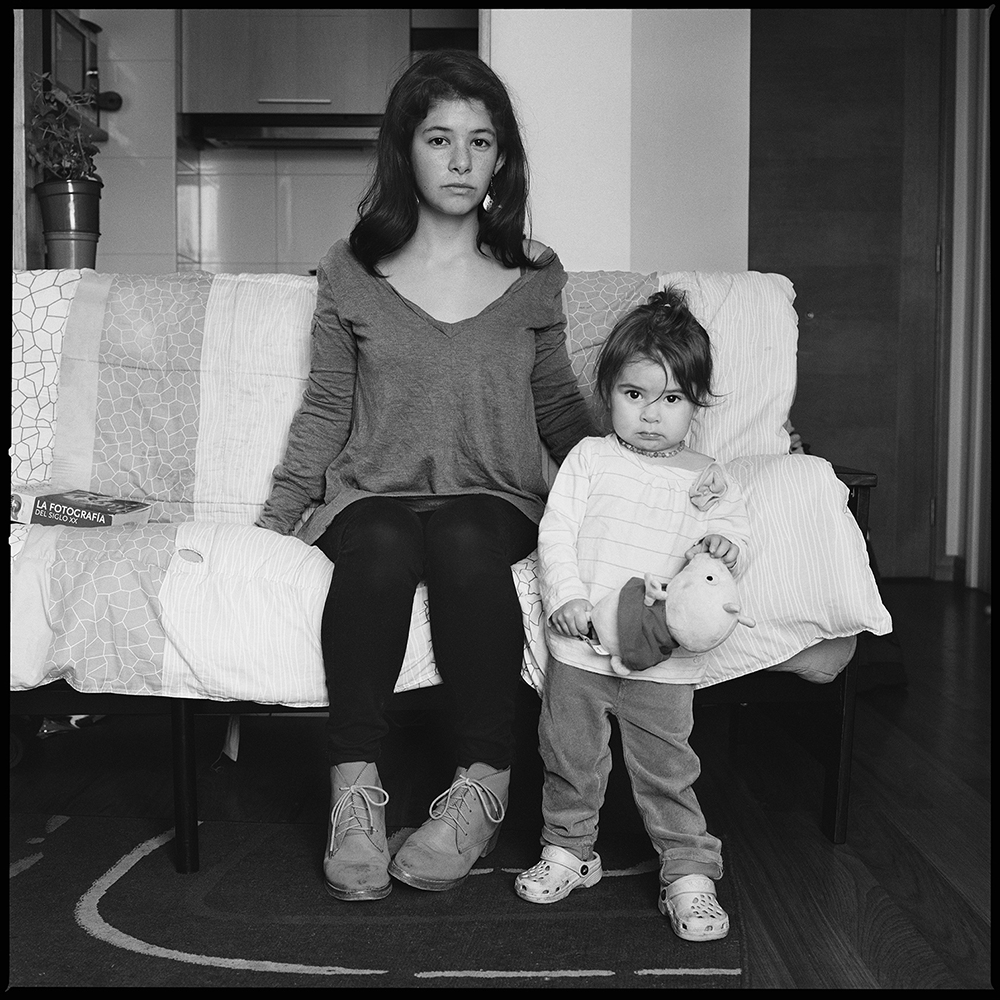

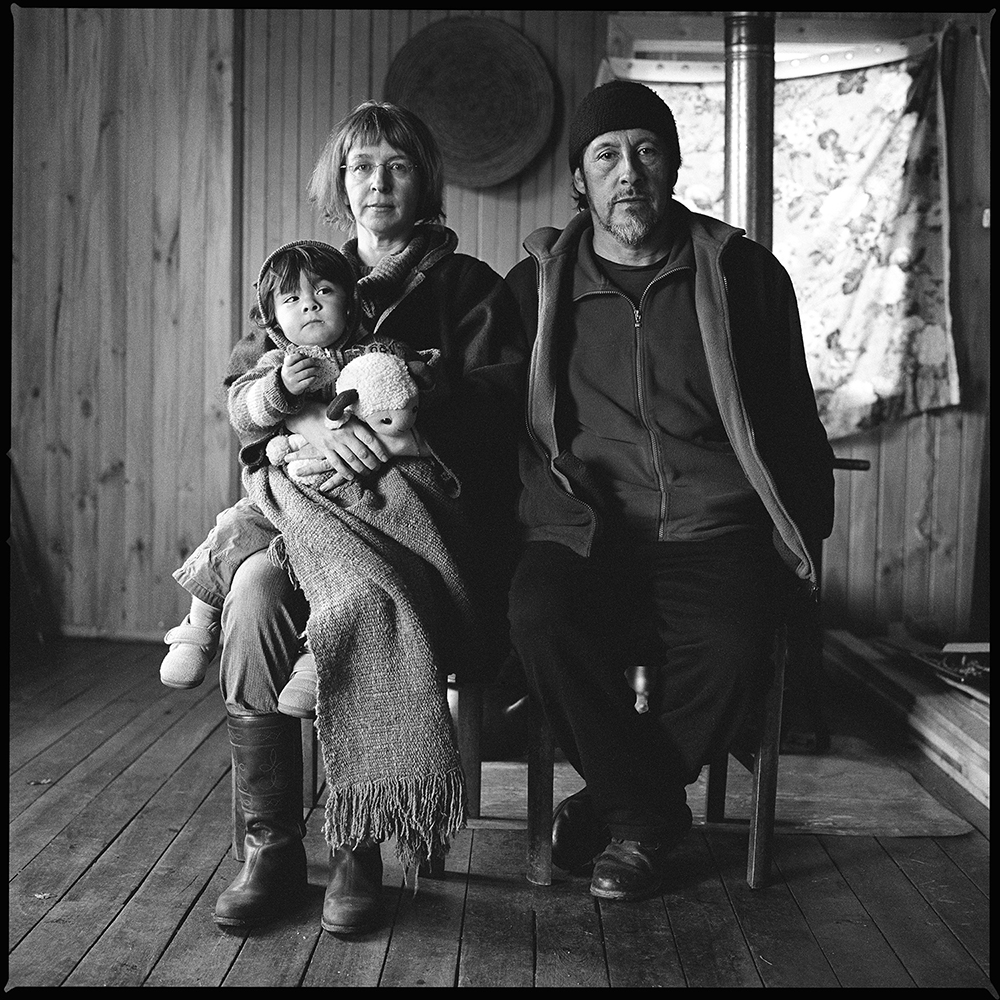

Guillermo González has spent the last three years considering the family portrait–its history, its context, and its legacy. These analog documents replicate the history of the formal portrait and share the notion that the truth behind a portrait is murky. I was struck by the intimate nature of these photographs, revealing clues of lives lived and gestures that speak to connectedness. I was most struck by the shoes–shoes that feel rooted to the earth, shoes that are not formal and are utilitarian. For me, those are the small truths of these images.

Guillermo Gonzàlez (b.1974) is a photographer and filmmaker who lives and works in Santiago de Chile. He studied at the Instituto de Arte de la PUCV (Institute of Arts of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso) where he studied filmmaking as well as photography with Bob Borowicz (Gold Medal, Baltimore Museum of Contemporary Art, USA). He has performed various jobs in documentary filmmaking, among which the most outstanding are: “Under the South,” “Register of Existence” and “Quinta.” At present, he is a professor at the Institute of Arts (Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso) in the Bachelor of Arts career. He is also coordinator of the Diploma Course of Analogue Digital Applied Photography, in the same institution. He also has a Master’s degree in Documentary Filmmaking from the Universidad de Chile.

Domestic

Photography has been considered, since its early stages, as a demonstration or a register of the real. To go to a photographic register tends to be confused with accessing the reality itself. This search of the “real” or the “reality” has accompanied man throughout all his history, nevertheless, the question is, what do these concepts imply? The idea of finding the access to a vestige of the past, to recognize who appears in an image, makes one proclaim that as a truth. But that image that we see and its protagonists are separated from this truth. Is it a reality or is it an artifice to bring something of the past into the present? The ones we see, are they really like that or is it an image built to endure in time?

We will try to find ourselves with an existing reality, but before us we find the estrangement of the impression of something that was and that has now changed.

“Situated in the intersection of presence, representation and metaphor, portrait is the most philosophic gender of photography, fluctuating between yearning and absence.”

(Córdova Carlos A., Leaflet of Shadows, Centro de la Imagen, Editorial, Mexico, 2012, Page 32).

Here Carlos Córdova aims towards desire and emptiness, as this estrangement effect comes hand in hand with the consciousness of the disappearance. This is how we photograph, we eternalize in images that we can use to affirm our memories.

Domestic is a project that reflects and cites the first family portraits, symbol of the status of the family able to afford the luxury of the register with a great preparation: gala outfits, jewelry and of course in the background, behind the family, the context that showed how they lived, what they possessed and their social rank. Thus, the family portraits of the mid 1800 show a hierarchy and social order, making visible the sober and good mannered family, such as so many others of the time.

Today, a family portrait has more to do with distinction than with homogenization. Although the family is a whole, it is understood that it is formed by individual subjects, different and distinguishable among themselves; that heterogeneity that the human being seeks at present, also appears behind the everyday family portrait. Families as a whole do not pretend to be the same as the rest anymore instead they know they are different in their composition, with different rules, hierarchies, and members. They are part of a global and changing reality.

The family portrait follows this same path of search, as it captures a built image of a family in front of a photographer for eternity. The work under analogue material and in black and white suggests the idea of registration and of truth, because in the first place the analogue image is generated from a physical mark, burning, on the material in contact with light; and on the other hand, the lack of color takes us back to the first photographs, which we culturally consider as historical registers.

A portrait as sample of a truth, not of an absolute truth, but as that generated in the agreement between photographed and photographer, that which involves the character of a family, already heterogeneous, composed by individual subjects and different among themselves, but crossed by the esthetic and constructive vision of whom handles the camera. Different families, different portraits, all different, cannot look like each other. Although they all appeal to a truth, a reality or a momentum of eternalization, every reality represented is unique.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Tom Zimberoff: The White Fence and more..March 2nd, 2026

-

The 2026 Black and White Portraits Lenscratch ExhibitionMarch 1st, 2026

-

The 2026 Black and White Portraits Lenscratch Exhibition | Part IIMarch 1st, 2026