Jim Lommasson: Stories of Survival: Object – Image – Memory

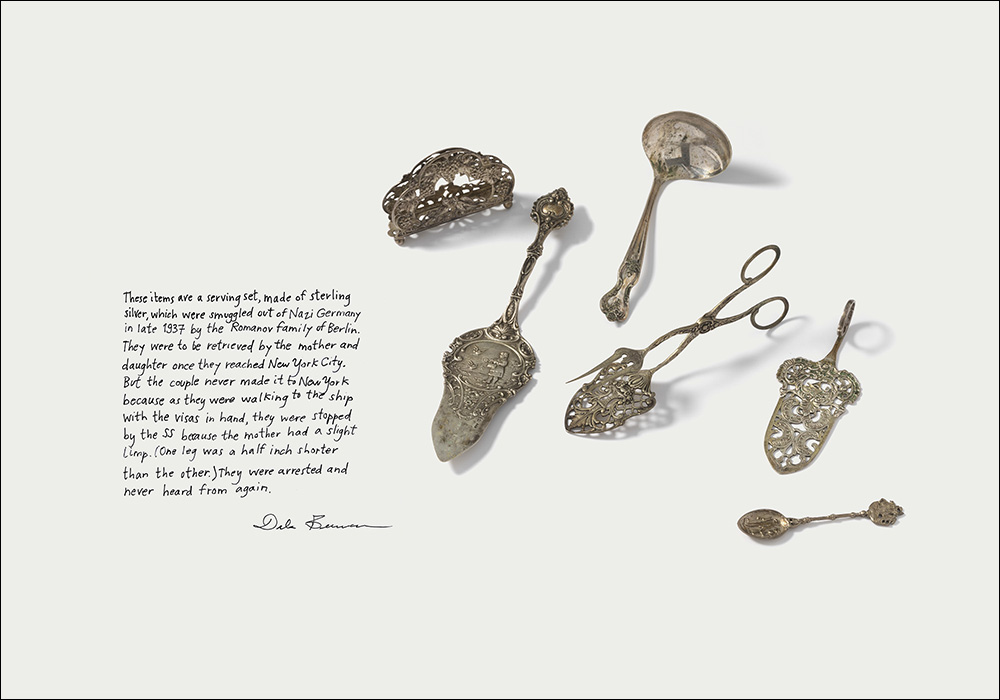

©Jim Lommasson, Serving Pieces (Germany, late 19th-early 20th century). These items are a serving set, made of sterling silver, which were smuggled out of Nazi Germany in late 1937 by the Romanov family of Berlin. They were to be retrieved by the mother and daughter once they reached New York City. But the couple never made it to New York because as they were walking to the ship with the visas in hand, they were stopped by the SS because the mother had a slight limp. (One leg was half an inch shorter than the other.) They were arrested and never heard from again. –Dale Berman, relative of the Romanov family

If your life were in danger and you had to leave your home immediately, with no hope of returning, what would you take with you? What would you leave behind?

Today I’m honored to share an interview with Jim Lommasson, the award-winning photographer behind Stories of Survival: Object, Image, Memory at the Illinois Holocaust Museum on view through January 13, 2019.

Over two years, Lommasson photographed more than 60 items carried by Holocaust and genocide survivors who fled to safety in America. Survivors were then asked to engage with the photographs and express themselves however they felt comfortable, directly on the print.

We talked about this unique, collaborative approach to visual storytelling, his background in documentary photography, and what’s next.

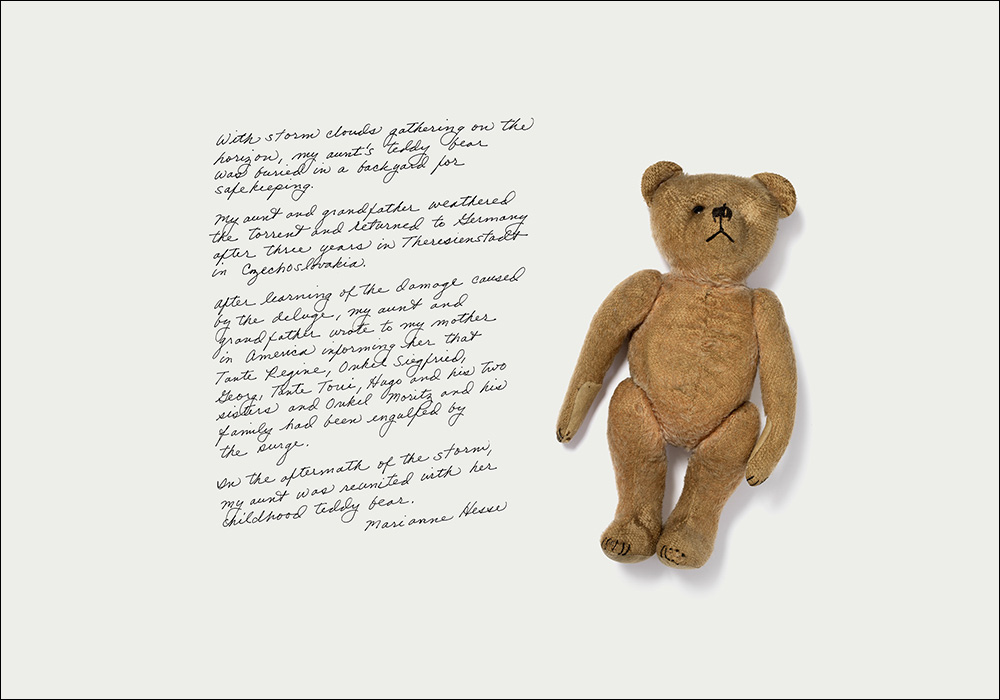

©Jim Lommasson, Teddy Bear (Bremen, Germany, ca. 1925). With storm clouds gathering on the horizon, my aunt’s teddy bear was buried in the backyard for safekeeping. My aunt and grandfather weathered the torrent and returned to Germany after three years in Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia. After learning of the damage caused by the deluge, my aunt and grandfather wrote to my mother in America informing her that Tante Regine, Onkel Siegfried, Georg, Tante Toni, Hugo and his two sisters and Onkel Moritz and his family had been engulfed by the surge. In the aftermath of the storm, my aunt was reunited with her childhood teddy bear. –Marianne Hesse

Jim Lommasson is an award-winning photographer and author living in Portland, Oregon. He received the 2004 Dorothea Lange–Paul Taylor Prize from The Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University for his first book, Shadow Boxers: Sweat, Sacrifice and The Will To Survive In American Boxing Gyms.

Lommasson’s 2015 book and traveling exhibition, Exit Wounds: Soldiers’ Stories – Life after Iraq and Afghanistan, profiles U.S. veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars, and their lives after war. It led to Lommasson being awarded an Oregon Humanities Conversation Project Grant for his public discussion “Life after War.”

His companion project, What We Carried: Fragments from the Cradle of Civilization, is an ongoing collaborative storytelling project with displaced Iraqi and Syrian refugees who have fled to the U.S. It was awarded a Regional Arts and Culture Council Project Grant, was published in 2016 by Blue Sky Books and has been widely exhibited in galleries and museums across the U.S. What We Carried will be exhibited at The Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration in New York City, May 28 – September 3, 2019.

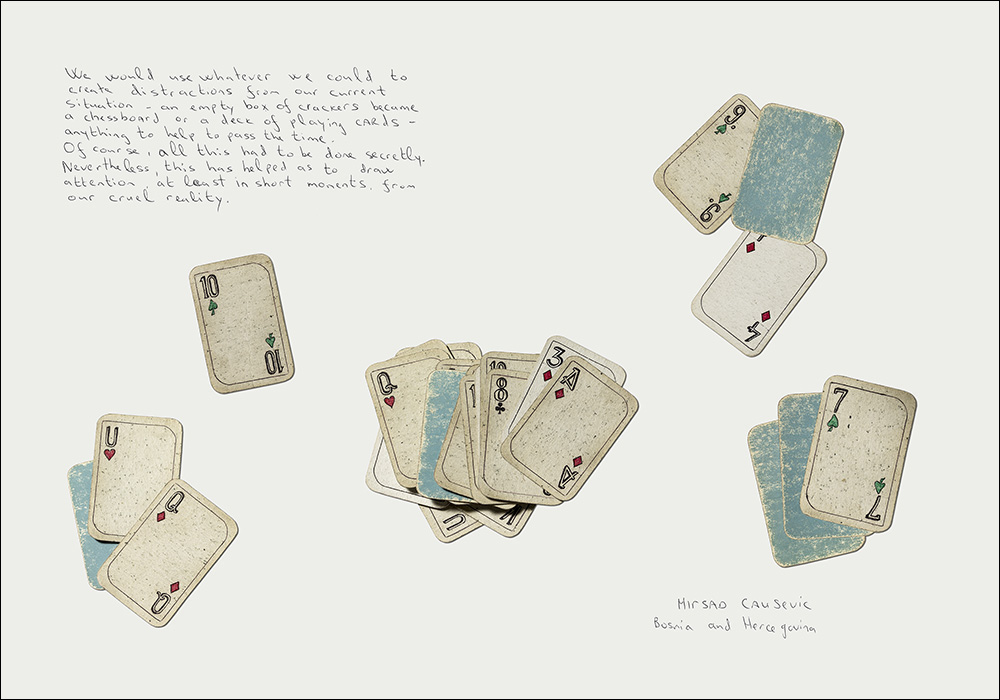

©Jim Lommasson, Handmade Playing Cards (Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1992). We would use whatever we could to create to create distractions from our current situation–an empty box of crackers became a chessboard or a deck of playing cards–anything to help to pass the time. Of course, all this had to be done secretly. Nevertheless, this has helped as to draw attention, at least in short moments, from our cruel reality. –Mirsad Causevic Prijedor

Stories of Survival: Object, Image, Memory

Illinois Holocaust Museum, July 16, 2018 – January 13, 2019

“I was living in Germany in the thirties, and I knew that Hitler had made it his mission to exterminate all Jews, especially the children and the women who could bear children in the future. I was unable to save my people, only their memory.” – Roman Vishniac

We often think about war and its aftermath, as though there were a clear demarcation between the two. Few ponder the tectonic forces, the signs and omens that portend the end of an era. But Vishniac saw the war looming, and urgently began to document a way of life on the verge of extinction.

My recent projects, Exit Wounds: Soldiers’ Stories – Life after Iraq and Afghanistan; What We Carried: Fragments from the Cradle of Civilization; and Stories of Survival: Object · Image · Memory, have been driven by a desire to illuminate the darkness and give voice to the silenced.

Inspired by the model developed for What We Carried, Stories of Survival is a collaborative photography and storytelling project with Holocaust and genocide survivors who fled to safety in the America. It centers on objects they were able carry with them on perilous journeys. From my photograph of the object, the participant responded with a story, a memory, a poem or a drawing. Their stories speak to the luminous inner life of these ordinary things and testify to the unspeakable anguish of a life forever left behind.

Shortly after What We Carried opened at the Illinois Holocaust Museum in January 2016, Museum staff asked me to create a similar project with Holocaust Survivors. Over a two-year period, the project expanded to include objects and stories from a too-long history of genocide in Armenia, Bosnia, Cambodia, Iraq, Rwanda and South Sudan.

Roman Vishniac’s impulse to photograph what he saw on the horizon in Europe was prescient. It’s clear to me that the currents of hate and bigotry still run strong. Stories of Survival memorializes those lost and those who survived, but it is also a call to action. We need to listen, and act. – Jim Lommasson

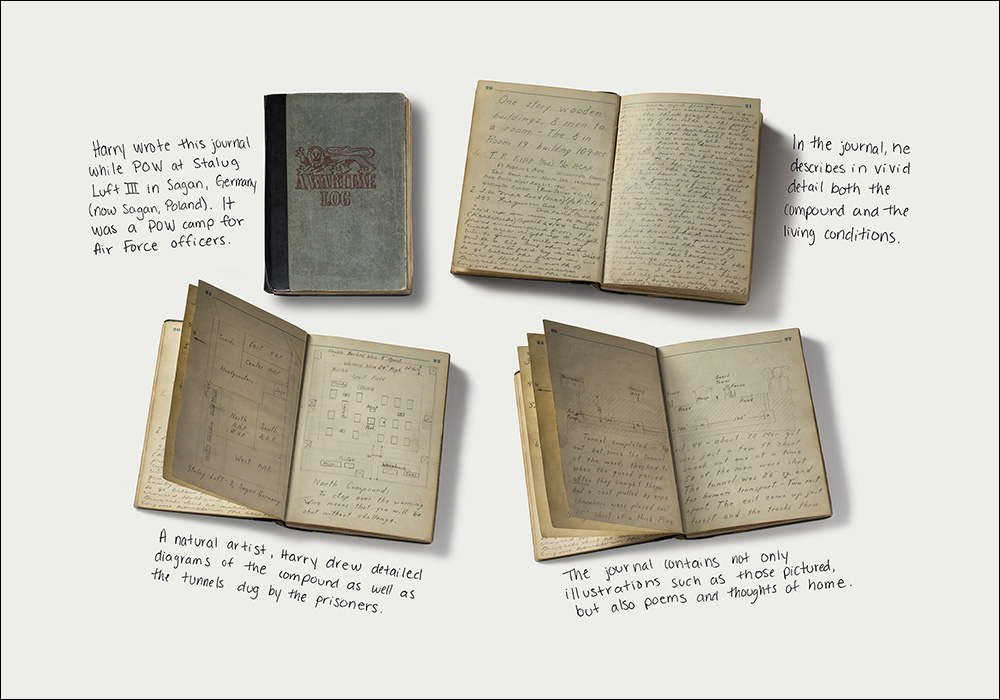

©Jim Lommasson, A Wartime Log for British Prisoners (Sagan, Germany, 1944). Harry wrote this journal while POW at Stalug Luft III in Sagan, Germany (now Sagan, Poland). It was a POW camp for Air Force officers. In this journal, he describes in vivid detail both the compound and the living conditions. The journal contains not only illustrations such as those pictured, but also poems and thoughts of home. A natural artist, Harry drew detailed diagrams of the compound as well as the tunnels dug by prisoners. –Craig Reuse, son of Harry Reuse

Megan Ross: Can you talk about your journey as a photographer? When did you start taking photographs?

Jim Lommasson: When I was ten, in the 1960s, my parents took me to Montgomery Wards. I’d always go to toy aisle to look at microscopes and chemistry sets. One day I found a darkroom kit with a little contact printer that you could print a 2 ¼ negative, and three trays for developer, stop bath and fixer. I remember setting it up in a closet in my bedroom. It was magic. It was alchemy! For me it was less about photography than it was the darkroom experience. But I had to take pictures to get back to the darkroom, so I did.

I went to an all boys’ technical high school where I majored in graphic arts. I learned about printing presses, setting type, photography, and art. I gravitated to photography and spent most of my time in the darkroom. Then I went to Portland State University and majored in sociology but couldn’t pass statistics. So I ended up in the art department taking photography classes.

One of the most profound experiences for me was a night critique class. A classmate had a young daughter that she brought to class one night when she couldn’t find a babysitter. The professor was describing some prints up on the wall, asking us to consider the luminosity and tonal range. The little girl was bored and said, “So what?”

I thought, wow. That’s a good question to ask about a photograph. That became a mantra for me. My career has been about making pictures that can have an answer to so what.

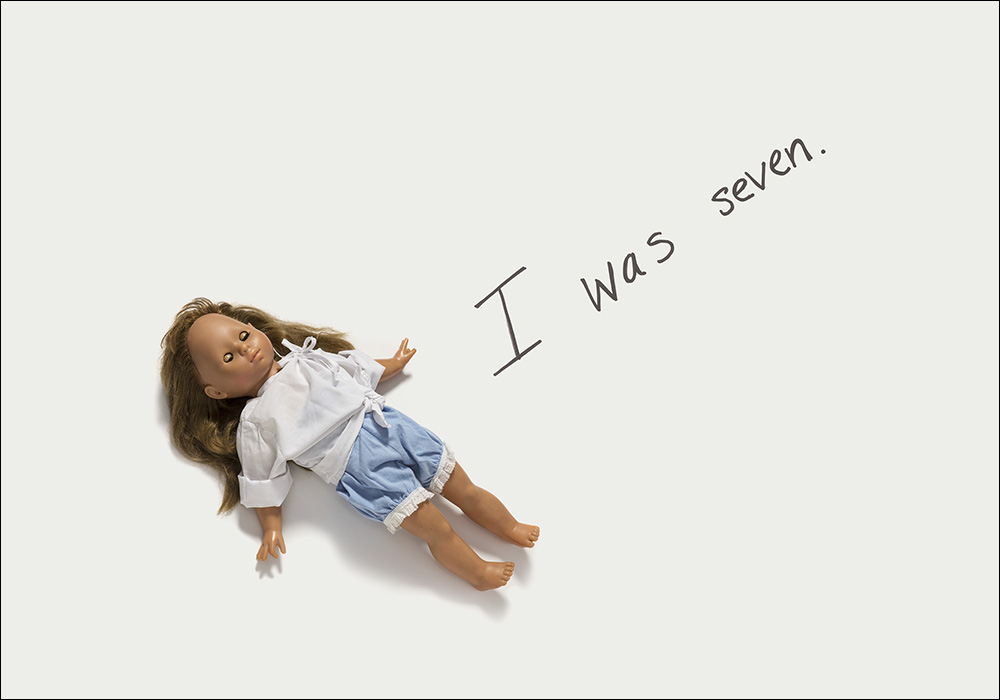

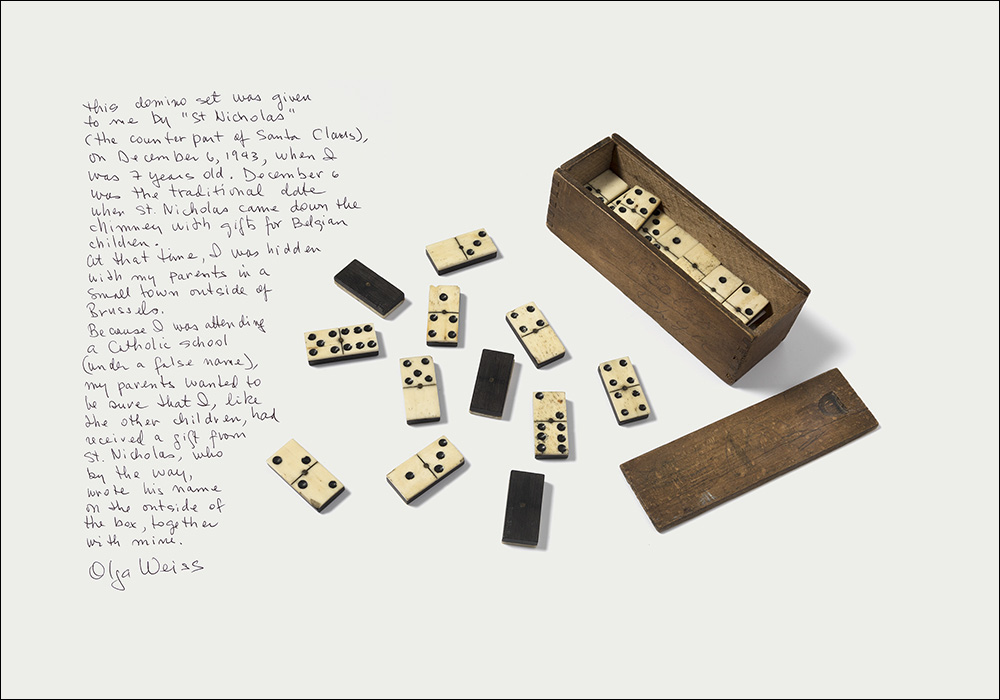

©Jim Lommasson, Domino Set (Brussels, Belgium, 1943). This domino set was given to me by “St. Nicholas” (the counterpart of Santa Claus), on December 6, 1943, when I was 7 years old. December 6 was the traditional date when St. Nicholas came down the chimney with gifts for Belgian children. At that time, I was hidden with my parents in a small town outside of Brussels. Because I was attending a Catholic school (under a false name), my parents wanted to be sure that I, like the other children, had received a gift from St. Nicholas, who by the way, wrote his name on the outside of the box, together with mine. –Olga Weiss

MR: Who were your photographic influences?

JL: Cartier-Bresson, Irving Penn, Lewis Hine—I spent a day with Roman Vishniac and that was a key thing. I love Irving Penn’s series of detritus found on the streets of NYC. I’ve always love how he transformed ordinary objects into things of beauty. When I started What We Carried I didn’t realize that Penn’s photos were an influence until much later. But mostly the 70s semi-street photographers. People like Hine—people who made a difference. When I saw their work, I realized I had this toolkit and could apply it to do something meaningful.

MR: Your projects seem to unfold organically, with one leading to the next. Can you describe how Stories of Survival came about?

JL: In 2007 I began a project about returning soldiers from the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars [Exit Wounds]. When I began interviewing returning veterans, I felt that I should interview someone from Iraq.

I found an Iraqi psychologist here in Portland and asked her opinion of the war. She said: “I thank America for removing Saddam Hussein, but did you have to destroy our country?” It was a powerful statement. I thought, I need to bookmark that and return to it.

As I was finishing Exit Wounds in 2010, I began a collaborative photography and storytelling project about refugees who fled their homes after the US invasion of Iraq [What We Carried].

Years later, What We Carried had been traveling around America, and the Illinois Holocaust Museum hosted it in 2016. At the opening, Susan Abrams [CEO of the museum] asked if I would do a similar project with Holocaust survivors. That stopped me in my tracks. I said yes, absolutely – and we have to start right away because the survivors are getting older.

MR: You could have photographed the objects in isolation, or made portraits of your subjects. Why include the handwritten stories?

JL: When I began What We Carried, I actually started with portraits – I photographed refugees in their apartments. I envisioned a book similar to Exit Wounds with a portrait on the left page and a story on the right. But the photos didn’t speak. I did it for six months, but I was never satisfied.

One day I was photographing a woman in her apartment, and I saw a family portrait on her desk and asked her about it. She said that when she left Iraq, it was one of two things she took with her along with her Q’uran. It was the only copy she had, and she asked if I would make some copies for her.

Later, while I was reviewing my images I came across those few frames of the family portrait. I realized I had something. This photograph spoke more to leaving one’s homeland — maybe under duress, maybe with a child under each arm.

I also considered photographing the objects in isolation and putting interviews next to the photos. But I know that in a gallery setting, most people won’t read a lot of text. I thought, what if I ask the participant write directly on the photographs? So I made a few photographs with lots of white space and asked this woman to tell me her story. She wrote the most beautiful story about how deeply saddened she was when she left her home.

That was the ah-ha moment. From there, the project took on a life of its own.

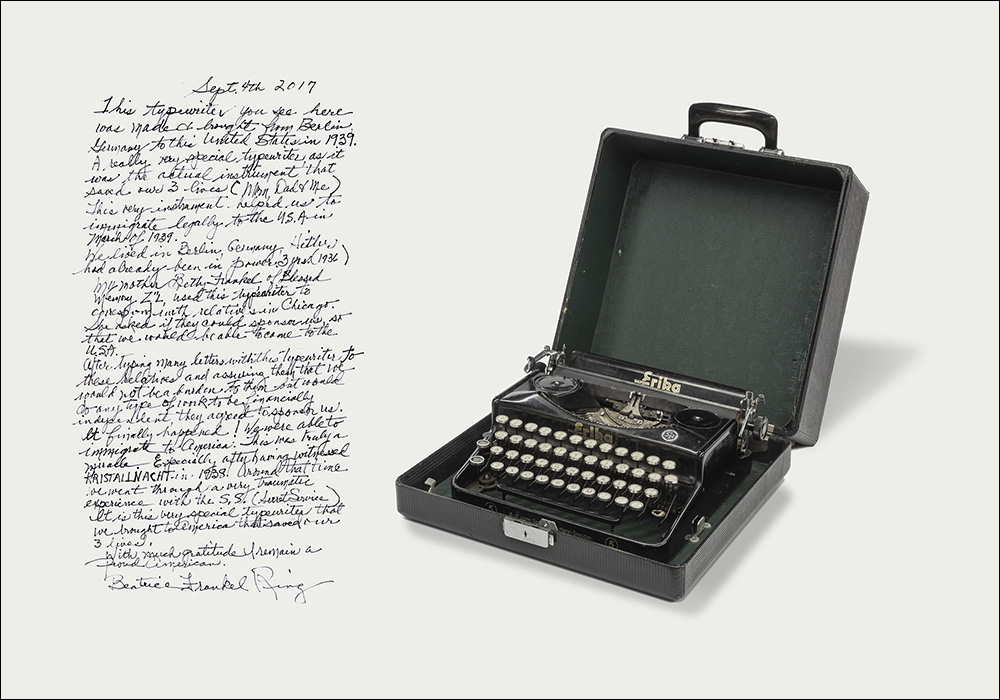

©Jim Lommasson, “Erika #5” Seidel & Naumann English Typewriter (Germany, ca. 1938). This typewriter that you see here was made and brought from Berlin, Germany to this United States in 1939. A really very special typewriter, as it was the actual instrument that saved our 3 lives (Mom, Dad and Me). This very instrument helped us to immigrate legally to the U.S.A in March of 1939. We lived in Berlin, Germany, Hitler had already been in power for 3 years (1936). My mother, Betty Frankel, of blessed memory Z’’L, used this typewriter to correspond with relatives in Chicago. She asked if they could sponsor us, so that we would be able to come to the U.S.A. After typing many letters with this typewriter to these relatives and assuring them that we would not be a burden to them but would do any type of work to be financially independent, they agreed to sponsor us. It finally happened! We were able to immigrate to America. This was truly a miracle. Especially after having witnessed KRISTALLNACHT in 1938! Around that time we went through a very traumatic experience with the S.S. (Secret Service). It is this very special typewriter we brought to America that saved 3 lives. With much gratitude I remain a proud American. –Beatrice Frankel Ring

MR: What was it like, emotionally, to immerse yourself in stories of genocide for almost two years?

JL: There are times when I was down in the basement of the museum in tears. I was just doing the photograph and I would read the notes… and I would understand gravity of what that object was and what it meant.

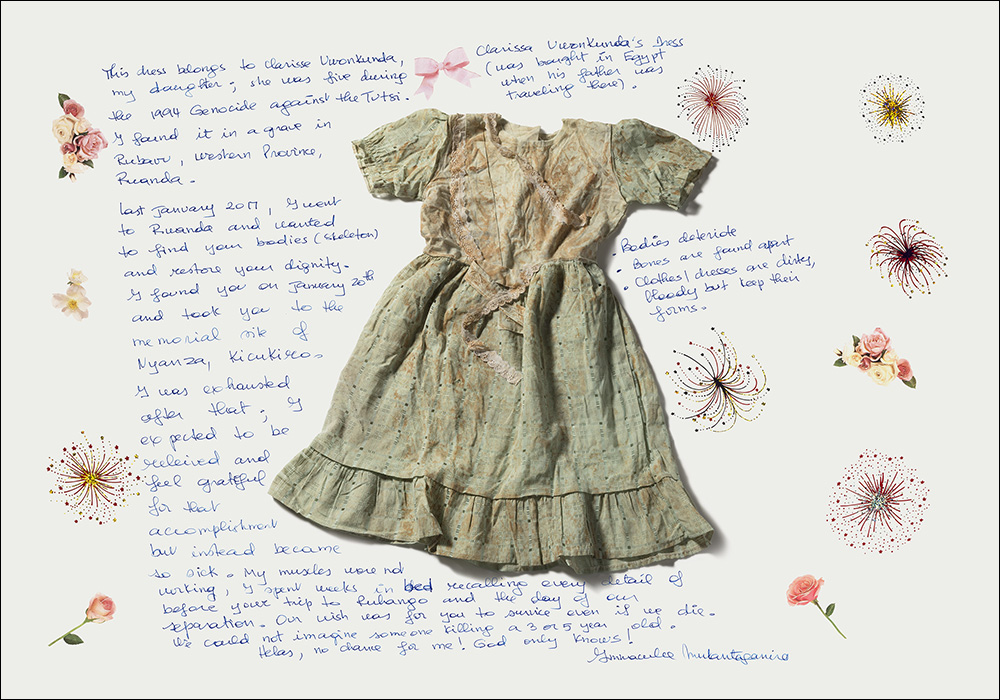

One in particular stood out, a woman from Rwanda. Her two toddlers and her husband were killed in the genocide. After the war, she went back to try to find the remains of her family. There was a ditch that had been opened up that was discovered to be a mass grave. The only way she could identify her daughters was by seeing their dresses. When I handled the bloodstained green dress, I just lost it. We all know how much we love our children and what a horrible thing it must be for a mother to go through that.

These stories are specific to genocides in our time, like the Holocaust, but they’re not just about history. They are about humanity.

©Jim Lommasson, Clarisse Uwonkunda’s Dress (Egypt, ca. 1994). This dress belongs to Clarisse Uwonkunda, my daughter; she was five during the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi. I found it in a grave in Rubavu, Western Province, Rwanda. Last January 2017, I went to Rwanda and wanted to find your bodies (skeleton) and restore your dignity. I found you on January 20th and took you to the memorial site of Nyanza, Kicukiro. I was exhausted after that; I expected to be relieved and feel grateful for that accomplishment but instead became so sick. My muscles were not working. I spent weeks in bed recalling every detail of before your trip to Ruhango and the day of our separation. Our wish was for you to survive even if we die. We could not imagine someone killing a 3 or 5 year old. Helas, no chance for me! God only know! –Immaculee Mukantaganira. (Note at right: Clarissa Uwonkunda’s Dress (was bought in Egypt when his father was traveling there). Bodies deteriorate; Bones are found apart; Clothes/dresses are dirty, bloody but keep their forms.

MR: How do you want viewers to feel when they leave this exhibition?

JL: The stories are so human, so powerful. I really see myself as conduit for their stories. I use photography because that’s what I do; it’s part of my toolkit. But it’s not about me.

What I learned is that when a person leaves their country, their journey isn’t a direct flight. Often, it’s a long walk that might lead to a refugee camp, or to a rubber raft floating to Greece. Some journeys take years. I hope the viewer puts themselves in the shoes of the refugee and starts to think… what would I take?

As we start to consider what we would take, we also find ourselves asking what we would leave behind. The answer is everything. Your family, your home, your culture. I want people to see this and realize—wow, they left everything, and now they’ve arrived in a country where they don’t speak the language. They have to start all over. And my hope is that this questioning starts a process of empathy and compassion.

It’s also a call to action. We’re realizing that many Americans have some ugly beliefs. I recently gave a presentation where I showed historical black and white photos from Nazi Germany. I contrasted those with color photographs of white supremacists with torches in 2017. They look very similar.

We must remember these stories of the Holocaust and genocide. My hope is that these stories will remind us of the inhumanity of war and the fragility of life.

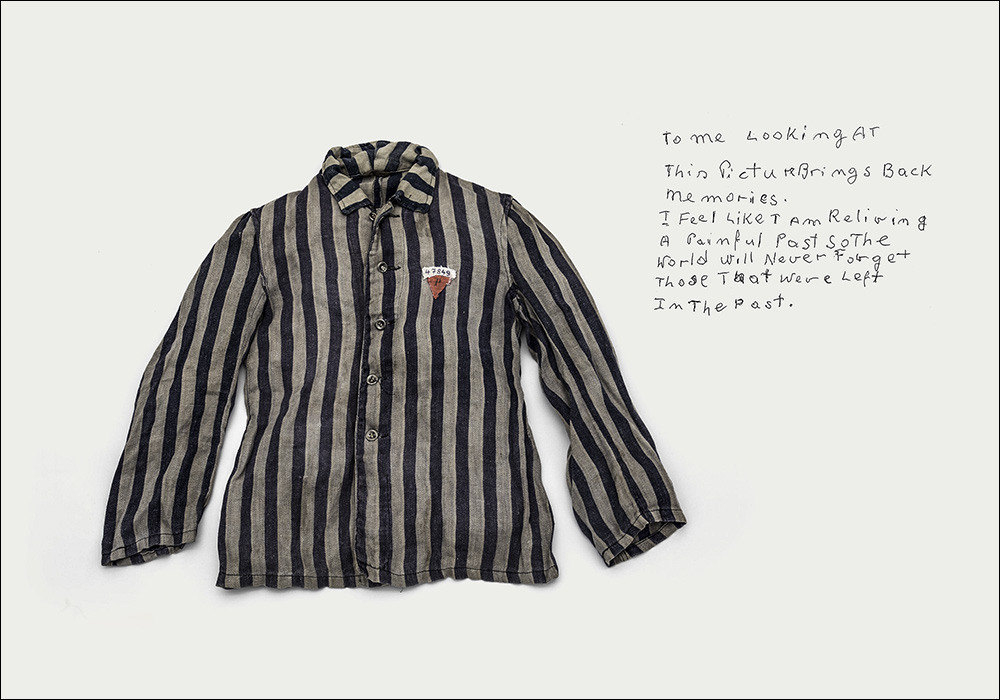

©Jim Lommasson, Concentration Camp Jacket (Flossenbürg concentration camp, Germany, 1945). To me looking at this picture brings back memories. I feel like I am reliving a painful past so the world will never forget those that were left in the past. –Henry Stone Nowy Targ

MR: What’s next for you? Any upcoming exhibitions or new projects?

JL: Stories of Survival is up through January 13. I will continue with What We Carried, which is currently traveling around America and will go to the Ellis Island Immigration museum in 2019 (Memorial Day – Labor Day). They say a half million people will see the show. I can’t imagine a better place for it.

Every once in a while I think, wouldn’t it be nice to do a project on the gardens of Tuscany? But I don’t see that happening.

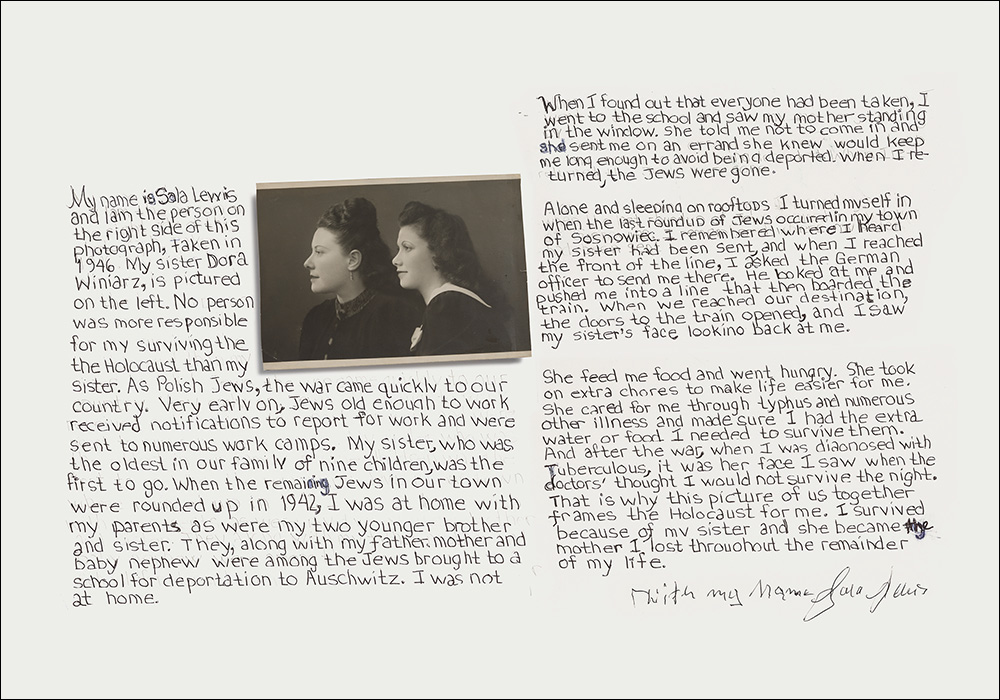

©Jim Lommasson, Photograph (Goslar, Germany, 1947). My name is Sala Lewis and I am the person pictured on the right side of this photograph, taken in 1946. My sister, Dora Winiarz, is pictured on the left. No person was more responsible for my surviving the Holocaust than my sister. As Polish Jews, the war came quickly to our country. Very early on, Jews old enough to work received notifications to report for work and were sent to numerous work camps. My sister, who was the oldest in our family of nine children, was one of the first to go. When the remaining Jews in our town were rounded up in 1942, I was still at home with my parents as were my two younger brother and sister. They, along with my father, mother and baby nephew were among the Jews brought to a school for deportation to Auschwitz. I was not home. When I found out where everyone had been taken, I went to the school and saw my mother standing in the window. She told me not to come in and sent me on an errand she knew would keep me long enough to avoid being deported. When I returned, the Jews were gone. Alone, and sleeping on rooftops, I turned myself in when the last roundup of Jews occurred in my town of Sosnowiec. I remembered where I heard my sister had been sent, and when I reached the front of the line, I asked the German officer to send me there. He looked at me and pushed me into a line that then boarded the train. When we reached our destination, the doors to the train opened, and I saw my sister’s face looking back at me. She fed me food and went hungry. She took on extra chores to make life easier for me. She cared for me through typhus and numerous other illnesses and made sure that I had the extra water or food I needed to survive them. And after the war, when I was diagnosed with tuberculosis, it was her face I saw when the doctors thought I would not survive the night. That is why this picture of us together frames the Holocaust for me. I survived because of my sister and she became the mother I lost throughout the remainder of my life. –Sala Lewis Sosnowiec, transcription by Evelyn Lewis, daughter of Sala

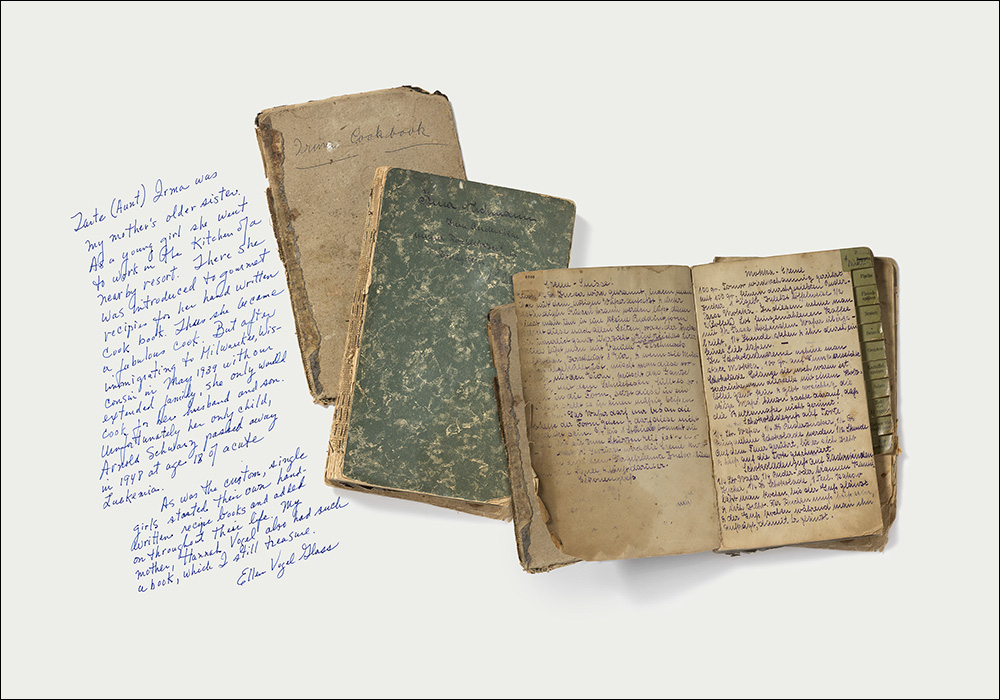

©Jim Lommasson, Cookbook (Germany, 1930s). Tante (Aunt) Irma was my mother’s older sister. As a young girl she went to work in the kitchen of a nearby resort. There she was introduced to gourmet recipes for her handwritten cookbook. Thus she became a fabulous cook. But after immigrating to Milwaukee, Wisconsin in May 1939, with our extended family, she only would cook for her husband and son. Unfortunately her only child, Arnold Schwarz passed away in 1948 at age 18 of acute Leukemia. As was the custom, single girls started their own hand-written recipe books and added on throughout their life. My mother, Hannah Vogel also had such a book, which I still treasure. –Ellen Vogel Glass, niece of Irma

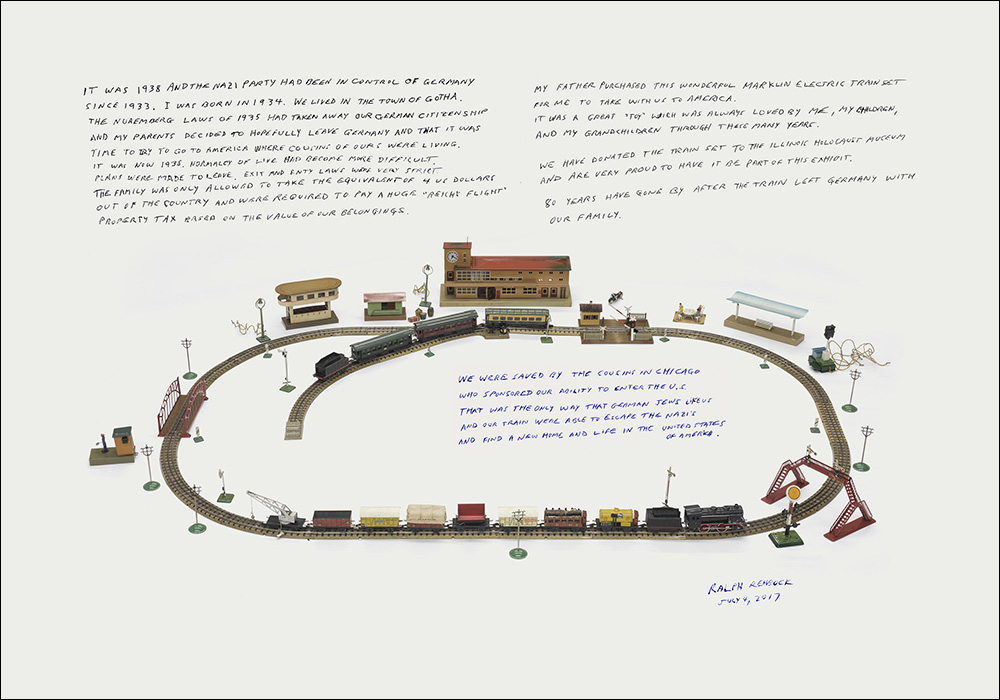

©Jim Lommasson, Marklin Train Set (Germany, 1938). It was 1938 and the Nazi party had been in control of Germany since 1933. I was born in 1934. We lived in the town of Gotha. The Nuremburg Laws of 1935 had taken away our German citizenship and my parents decided to hopefully leave Germany and that it was time to try to go to America where cousins of ours were living. It was now 1938. Normalcy of life had become more difficult. Plans were made to leave. Exit and entry laws were very strict. The family was only allowed to take the equivalent of 4 US dollars out of the country and were required to pay a huge “Reich Flight” property tax based on the value of our belongings. My father purchased this wonderful Marklin electric train set for me to take with us to America. It was a great “toy” which was always loved by me, my children, and my grandchildren through these many years. We have donated the train set to the Illinois Holocaust Museum and are very proud to have it be part of this exhibit. 80 years have gone by after the train left Germany with our family. We were saved by the cousins in Chicago who sponsored our ability to enter the U.S. That was the only way German Jews like us and our train were able to escape the Nazis and find a new home and life in the United States of America. –Ralph Rehbock, July 4, 2017

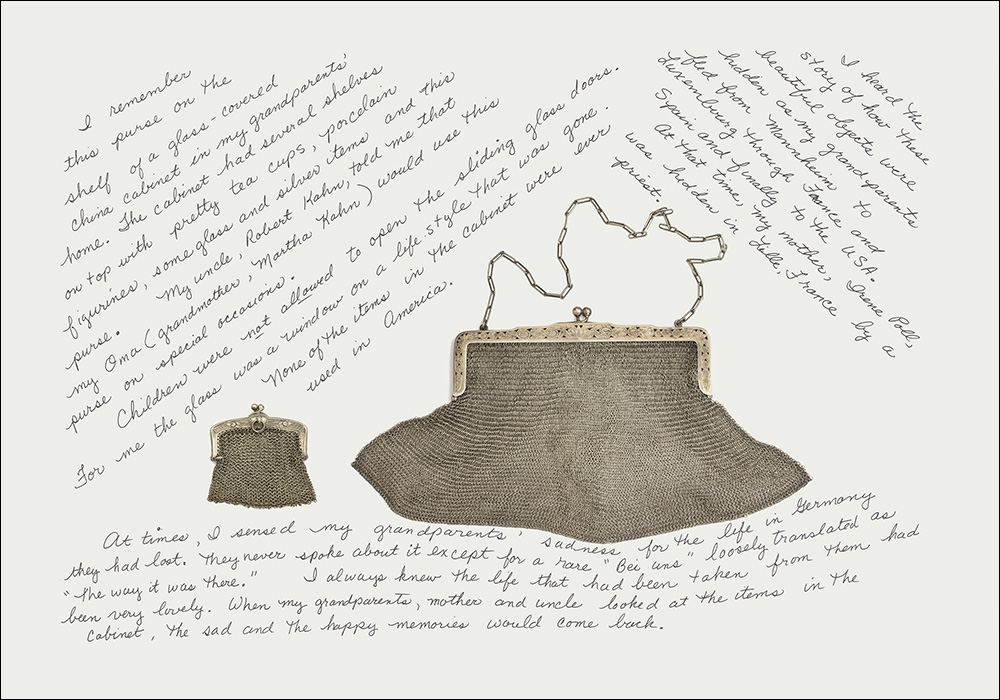

©Jim Lommasson, Evening Bag (Mannheim, Germany, pre-WWII). I remember this purse on the shelf of a glass-covered china cabinet in my grandparents’ home. The cabinet had several shelves on top with pretty tea cups, porcelain figurines, some glass and silver items and this purse. My uncle, Robert Kahn, told me that my Oma (grandmother, Martha Kahn) would use this purse on special occasions. Children were not allowed to open the sliding glass door. For me the glass was a window on a life style that was gone. None of the items in the cabinet were ever used in America. I heard the story of how these beautiful objects were hidden as my grandparents fled from Mannheim to Luxembourg through France and Spain and finally to the USA. At that time, my mother, Irene Poll, was hidden in Lille, France by a priest. At times, I sensed my grandparents’ sadness for the life in Germany they had lost. They never spoke about it except for a rare “Bei uns” loosely translated as “the way it was there.” I always knew the life that had been taken from them had been very lovely. When my grandparents, mother and uncle looked at the items in the cabinet, the sad and happy memories would come back. –Faye Schulz, granddaughter of Martha Kahn

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026