Ryan Stander: The States Project: North Dakota

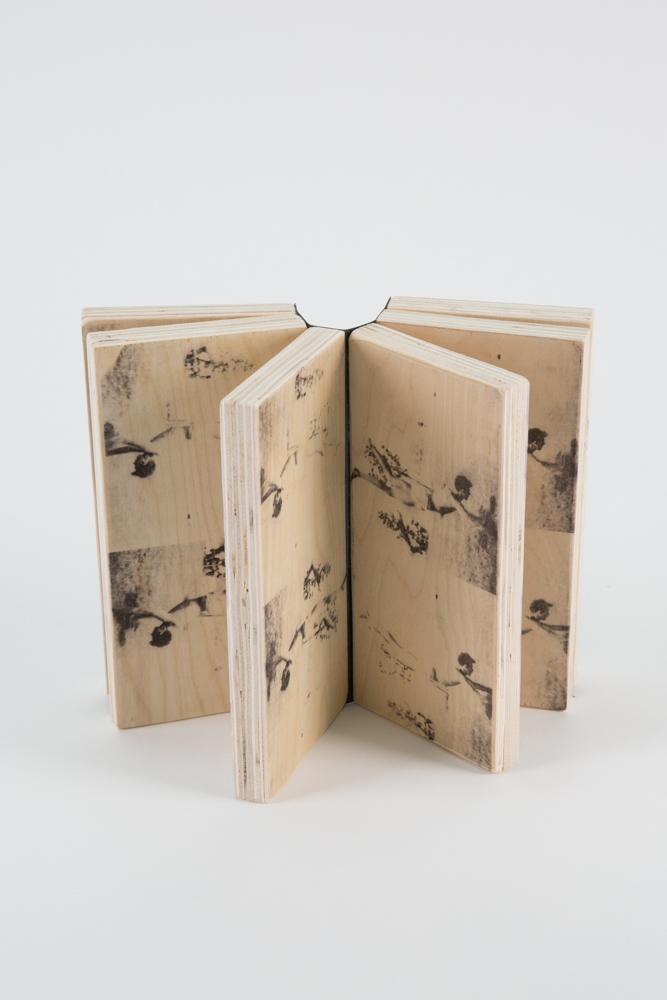

Ryan Stander is a dynamic visual artist working in Minot, a small city in the northcentral part of the state. Stander’s photography runs the gamut from black and white images of grain elevators to alternative process works books made up of instagram projects. Throughout all these series Stander exhibits a deep interest in material: surface, origin, and cultural connotation. Each of his projects represents a new avenue of inquiry into the relationship between material and the presentation of content.

This summer I had the opportunity to visit Stander’s “basement studio” and view his collections of found photographs, assemblages, and other printed series. Our conversation about his work (and photography) was broken up and fueled forward by the opening another closet door, finding a new box of images, and another drawer of experimental prints. It was difficult to choose a series for this post, but the one featured here represents two of his long-term interests: alternative processes and historical imagery.

Ryan Stander, is an Associate Professor of Art at Minot State University where he teaches photography, directs the BFA program, and co-directs Flat Tail Press. Originally from the farmlands of northwest Iowa, Stander is a transplant to central North Dakota. His education alternated between art and theology [MFA from the University of North Dakota, MA in Theology from Sioux Falls Seminary (SD), and a BA in Art from Northwestern College (IA)]. His research interests reside in conversations of art and theology with memory, identity, and landscape.

My current work explores the reciprocal relationship between humanity and a world of physical objects and places. In particular, I am interested in the cultural frameworks, including beliefs, biases, and assumptions that guide human interactions with the material world.

Through different series, materials and methods, the work attempts to explore and embody these cultural hermeneutics through the image and text.

Much of my work is photographic in nature; combining elements of my own photographs, found or purchased vernacular photos, or simply appropriated imagery that engages and challenges the viewers own preconceived, yet often unarticulated, assumptions about places, things, and identity. – Ryan Stander

You came to photography after pursuing theology and seminary. How has this background influenced your work? Your artistic practice as a whole?

Truthfully, I fell in love with photography as a child. My father influenced my earliest interest in photography. He purchased a Voigtlander Vitessa while stationed in Germany in the late 50’s and it served as our family’s camera throughout my years at home. For me, some kind of magic came from that device.

My undergraduate degree was in art where I spent most of my time between photography and printmaking. But nearing the end of my college career, I began to explore issues of art and theology. Ultimately this brought me to the academic pursuit of theology in seminary, which gave me a solid theoretical framework to work through. It may not be evident in all my work but it is always a conversation partner in my mind as I am working. When I am making art, I am thinking about theology and vice-a-versa.

You haven’t always lived in North Dakota. How has this place changed or influenced your work?

I grew up as a farm kid in Iowa, rooted to the land and its seasons as farmers are. I didn’t realize how much I was tied to this community until I left it. But by leaving it, I began to recognize that reciprocal relationship with the landscape…how in forming it, it forms us.

I moved to North Dakota 10 years ago and have lived in 2 distinct regions of the state. When I moved to Minot, it was reeling from a devastating flood and a peaking oil boom. My interests in landscape continued as I joined a group researching the “man camps” and temporary housing options for oil workers. The boom and flood provided a deep resonance with my previous work.

What is the best part about living and working in North Dakota as an artist?

Once I was presenting at paper at a theology conference at Notre Dame someone said incredulously, “There are artists in North Dakota?”. Yes…Yes there are. The arts community is small, but vibrant. We may be somewhat isolated (which is difficult), but artists here are showing across the country and doing strong work. Both my university and the North Dakota Council on the Arts have supported my work with numerous grants and an Arts Fellowship. I am so thankful for their support!

Do you feel that having a photographic community is important? What is your impression of the community in North Dakota?

Community in the arts is absolutely critical wherever you are. A few years back, in my first years of teaching, I organized print exchanges among photographers of the Dakotas and printmakers of the region, which were critical for me to meet and get to know many of the artists in the region.

As artists, we are spread across the state. As a result, the museums and galleries in the region are critical places that gather, sustain, and activate the arts across the state. Places like the North Dakota Museum of Art in Grand Forks, The Plains Art Museum in Fargo, the Northwest Arts Center in Minot, and others are cultural hubs for the state.

What are some concepts and themes you hope to cover through your work, in any of your projects?

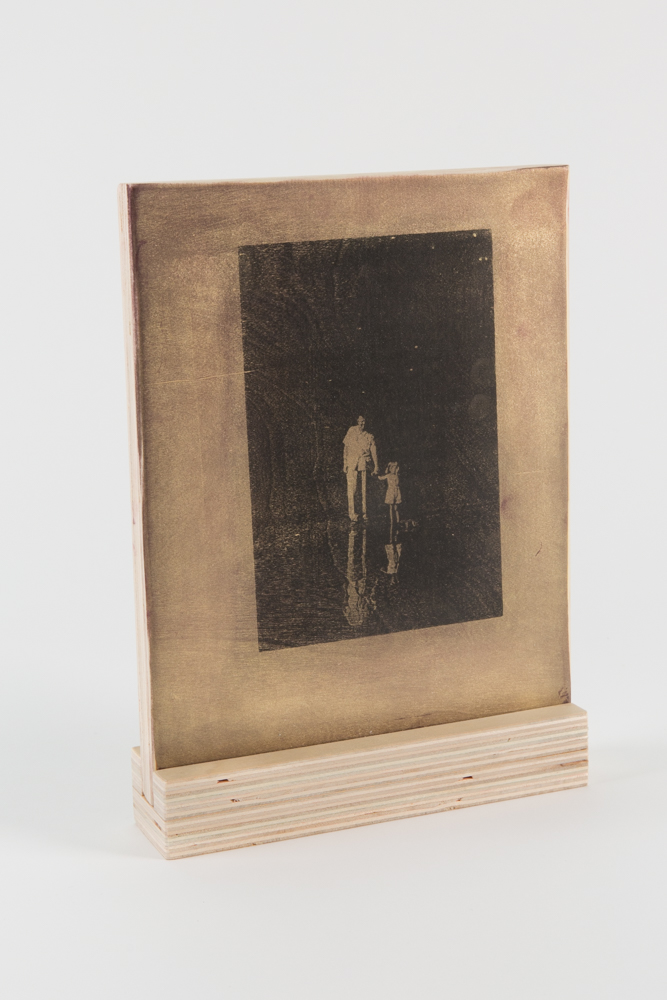

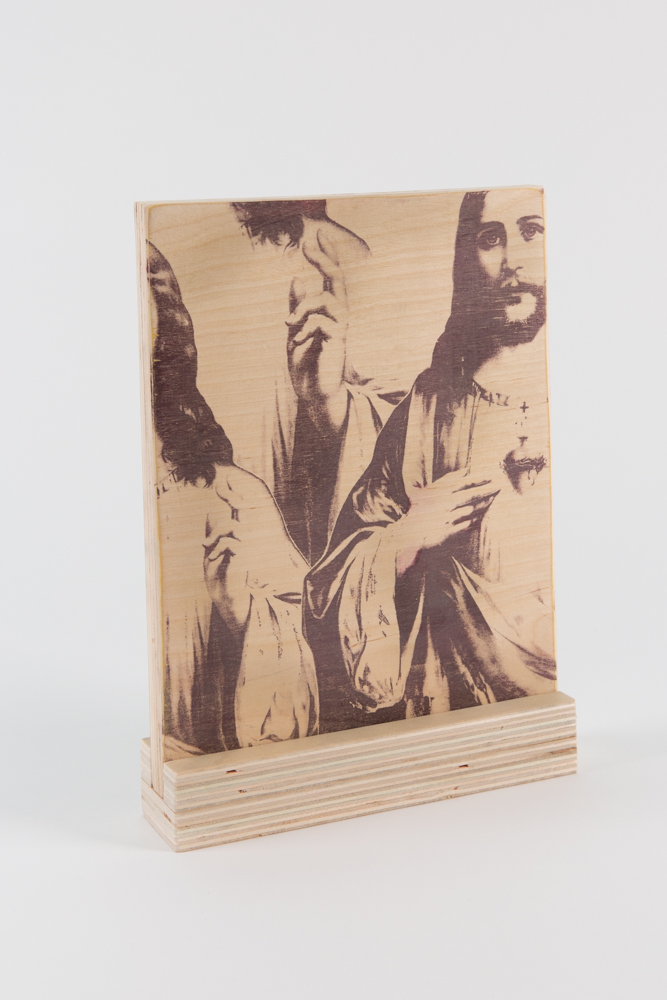

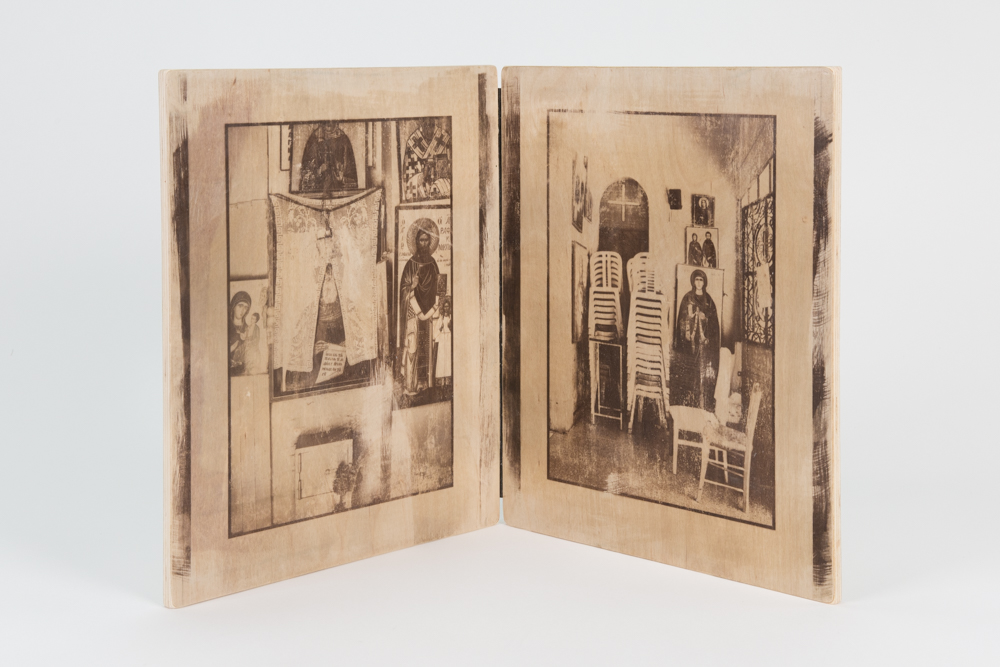

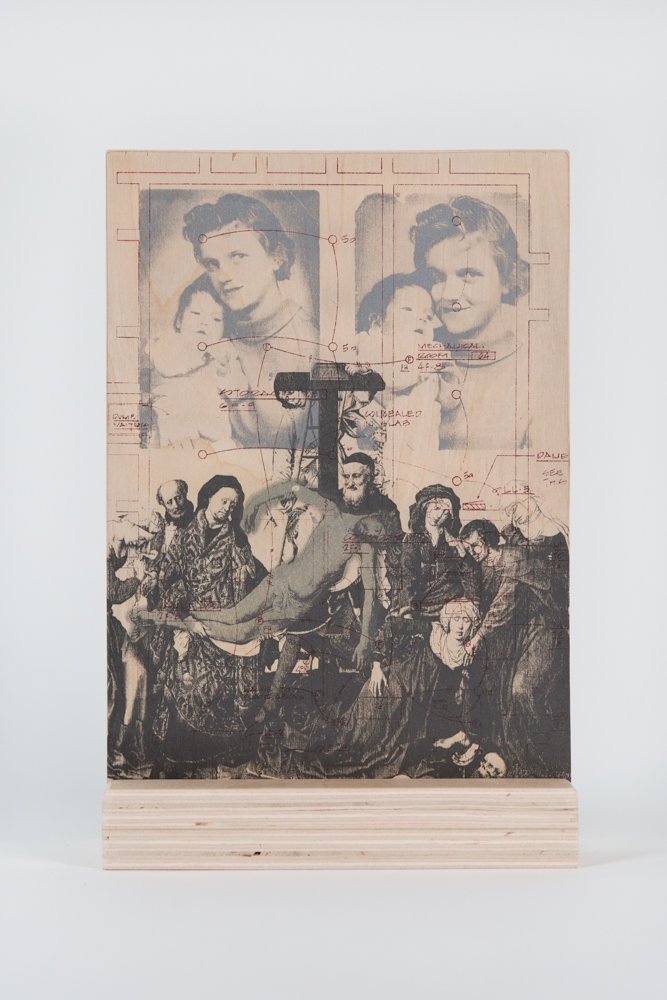

If I distill it all down, my work moves among conversations about the formation of place, memory, and identity and their interrelationships. My theological studies awoke an interest in the dynamics of formation. Whether it is ones family, religious outlook, political and national influences, cultural structures, they all play into how we understand our place in the world. While my work is rooted in my theological education, it is rarely just about religion or theology. By borrowing religious forms and imagery I’ll often explore related, but more expansive ideas than the original literal or intended use.

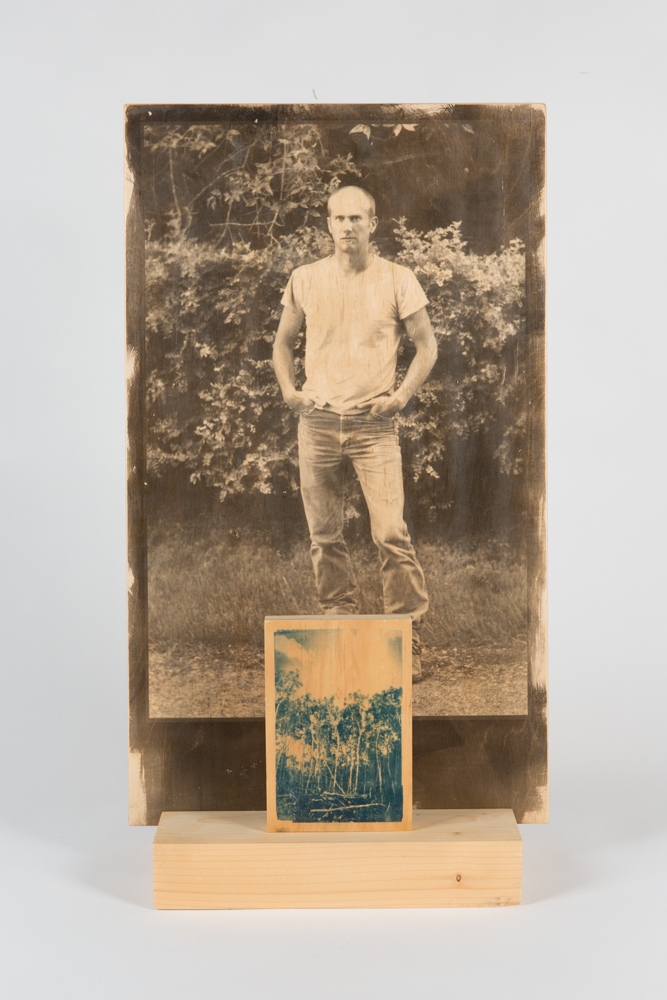

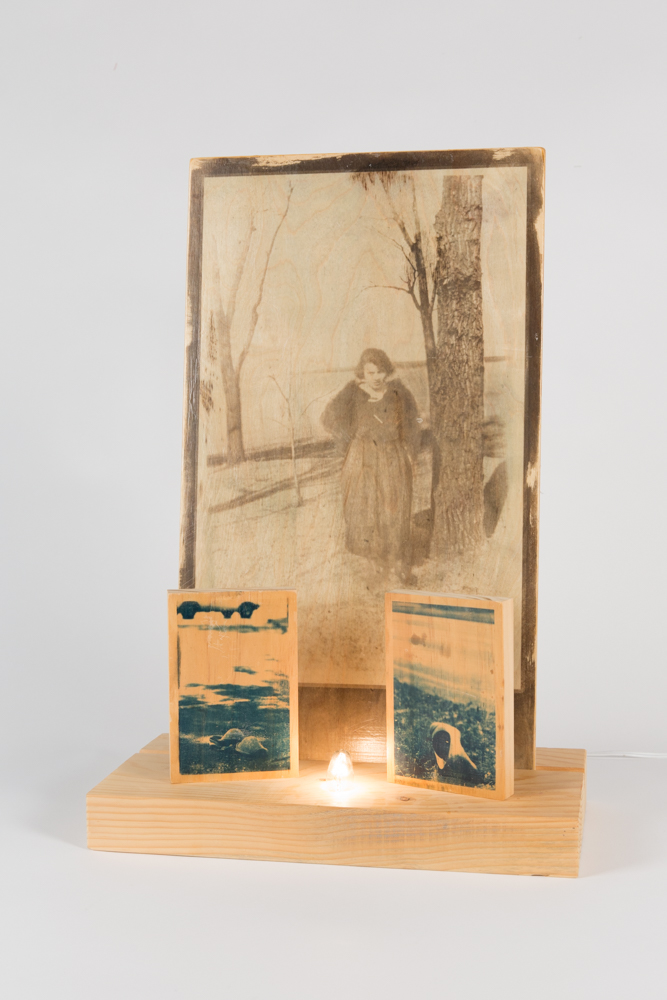

Much of my work over the past ten years has made use of vernacular photography to explore these ideas. In these wooden pieces, I borrow from Christian iconography, altars, and even tombstones, which all elicit a religious reading tied to memory and devotion. When exhibiting these and other works of vernacular photography, I’ll often offer both original objects and lithographs to evoke anonymity and raise questions about memory, legacy, and lost narratives.

Much of your work makes use of alternative processes and surfaces. What makes these methods and materials so interesting to you?

I discovered printmaking in college and fell in love with the physicality of making art. After a semester of digital editing in graduate school I desperately needed to return to a more physical way of making work or I wasn’t going to make it through. My interest in wood, plexi, metal substrates comes from that time with digital work. Digital work can lose the object nature of the photograph but moving back toward printmaking helped my pull the physicality of the object back into the conversation. For me, I tend not to draw lines between the two fields of photo and printmaking. It all depends on the piece whether I head to digital or traditional prints, alt. processes or an ink based printmaking process.

What’s next? Anything new you can share?

I’m working on a few random projects but nothing cohesive right now. It’s a period of transition and exploration I think. I visited Florence, Italy this past May and have a series of images that I am working through. I’m also working through a grant-funded project on post-digital printmaking using CNC’s, laser cutters, and 3-D printers. Who knows where, if anywhere, it will go, but I’m enjoying the journey.

©Ryan Stander, Lost Objects and Practices of Remembrance I Van Dyke, Cyanotype, Wax on Plywood with Electric Light

What are your favorite &/or most influential books?

A somewhat short list…

Dakota – Kathleen Norris, The New West – Robert Adams, Man is Not Alone – Abraham Heschel, Uncommon Places – Stephen Shore, Spaces for the Sacred – Philip Sheldrake, New Topographics – Britt Salvesen, My Name is Asher Lev – Chaim Potok, Approaching Nowhere – Jeff Brouws, Anamnesis as Dangerous Memory, The Fate of Place – Edward Casey, The Disappeared – Laurel Reuter, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek – Annie Dillard, Theopolitical Imagination – William Cavanaugh, Intimate Distance – Todd Hido, Consuming Religion – Vincent Miller, Early Color – Saul Leiter, Place and Placelessness – Edward Relph, Walking on Water – Madeleine L’Engle,

What is giving you inspiration these days? Something you are listening to, seeing, or reading?

Wonder. My mind has been occupied with the idea of wonder for a while now. I noted to a colleague years ago that too many students seemed to live without a real sense of curiosity and wonder. It is difficult to live with wonder in a world filled with hyperbole, sensationalism, and cynicism but is critical, especially for the artist. Whether it is found in the formation of a simple piece of popcorn, the folded movements of a sheer curtain in the breeze, or the way light moves across an architectural facade, wonder is at the heart of my creative process. Wonder springs from a surprised recognition that something is beyond my ken. Something previously unnoticed or unknown now comes to light, and points me toward a deeper appreciation of the world around me.

On a related front, my wife and I are teaching a paired set of classes this semester for freshman on yoga and photography. Our goal, for our students (and ourselves really), is to use the idea of mindfulness to be present in our world. Photography, as a practice and product, can help us to be present, aware, alert to, and attend to the world around us.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Vaune Trachman: Now IS AlwaysMarch 3rd, 2026

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026