Photographers on Photographers: McNair Evans and Matt Mimiaga

You learn a lot about a person when you’re lugging hundreds of pounds of equipment up a mountainside, driving a gear truck together at 4 Am, or accidentally leave them on a remote beach in Puerto Rico with nothing but a flashlight and the boxer shorts they are wearing. More memorable than his work ethic, passionate activism, and incredible stories of uncanny encounters with photography-greats such as Roy DeCarava, are Matt Mimiaga’s pictures. So when Lenscratch asked that I contribute a feature interview with a photographer that I admire, Matt was an obvious choice. Regardless of what project Matt is developing, his commitment to integrity, both in character and photographic process, imbue his images with earnest humanism and unflinching honesty. Drawn from a variety of projects, the photographs.

Matt Mimiaga was born in San Francisco, California in 1984. In 2006, he received a B.A. from the Gallatin School of Individualized Study at NYU. His self-assigned projects document the contemporary American social landscape. Matt currently resides in Oakland, California with his wife and dog.

Matt Mimiaga was born in San Francisco, California in 1984. In 2006, he received a B.A. from the Gallatin School of Individualized Study at NYU. His self-assigned projects document the contemporary American social landscape. Matt currently resides in Oakland, California with his wife and dog.

McNair Evans: People ask me how I decided to become a photographer. For me it wasn’t as much a decision as a realization. What about you… when did you realize photography was something you needed to take seriously?

Matt Mimiaga: I was obsessed with Kubrick in high school and I learned that he had started off as a photographer. Once I started taking pictures I fell in love. It was this whole other language. The camera changes the way you look at things and forces a new interaction with the world. The ambiguity of frozen time and the preconceptions the viewer brings make it simultaneously objective and subjective— a beautiful paradox. I love this Winogrand quote, “I have a burning desire to see what things look like photographed by me.” Now that everyone carries a camera in their pocket, you can see that kind of visual literacy spreading. People are noticing beautiful absurdity in their daily life, they’re paying attention to light, even if it’s just for a selfie or food shot, and there’s this shift in power now that more people have the ability to document injustice and abuse. I don’t know how much of a pedestal there will be for individual photographers in the future, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but this is a byproduct of the democratization of image-making, which captures so much more than ever before.

ME: You’ve mentioned Jacob Holdt, Nan Goldin, Larry Clark, Anders Peterson, Miguel Rio Branco, Donna Ferrato, Jamel Shabazz, Daido Moriyama, and Joseph Rodriguez as some of your inspiration, teachers (in Joe’s case), and heroes. Will you share a quick nugget or lesson you take from each of them?

MM: I have to start with Joseph Rodriguez because his mentorship is at the core of everything. Joe taught me that if you want to make intimate photos you have to get close. I was familiar with Ballad of Sexual Dependency and Tulsa, but I didn’t yet fully appreciate what goes into making work like that. Nan and Larry started with their close friends and family, but Joe would find people and connect with them, developing these deep relationships. You can see it in his photographs. He showed me a lot of other photographers that work in this way, which is how I became familiar with Anders Peterson, Miguel Rio Branco, Donna Ferrato, and Jacob Holdt. Early in his career, Joe spent time in Stockholm and got to know Anders Petersen. A quote from Anders that always stuck with me is, “you always have time, you’re always losing time.” Very zen, but time is everything in photography. Not just the decisive moment, but time spent on relationships, time passing between visits, time of day, evidence of time on the objects the frame. There’s a great interview with Anders you can find on YouTube where he talks about shooting Cafe Lehmitz.

He would keep his camera visible always so no one got the impression he was sneaking, and he’d express interest in photographing someone, but then just chat with them until they ask him to take their picture. That change—where the subject wants to be photographed—is really important. I’ve always been haunted by the domestic violence Donna Ferrato captured in Sleeping with the Enemy, and how close she had to get to such terrifying situations. Her book Love and Lust is a unique historical document that celebrates promiscuity in NYC’s bygone sex clubs.

My Gigi’s series was made in the ashes of that world, after Giuliani shut all the clubs down. What I love about Daido Moriyama is the immediacy of his technique and the surreal ambiguity it gives his pictures. Miguel Rio Branco is a major color influence. Jamel Shabazz is the best example of how something as simple as street style can become an indispensable cultural document. It’s a mistake to think that technical proficiency is what elevates your art. My favorite photographers are part historian and part activist. Jacob Holdt is my second biggest influence after Joe. I think his book American Pictures should be required reading in our schools. Holdt’s understanding of race and class in America comes from having submitted himself completely to poverty, shedding the armor that money provides, which he saw as an obstacle to intimacy. He took the incredibly intimate photos with a cheap camera, and paid for the film by giving blood. The work uncovers actual slavery on southern plantations continuing still in the 1970’s, but beyond that he psycho-analyzes America as completely crippled by the toxic master-slave power relations that never ended post emancipation. He did this as a foreigner and from a completely humanistic perspective.

ME: The first pictures of yours that I saw were from your projects Silver Swan and Gigi’s. I was struck be the incredible content… activities and scenes that could have been classified as illicit or illegal. You’ve described that community as, “an anything-goes lifestyle where sex and drugs are rituals in the performance of identity.” What aspects about that group and their activities enticed you to make pictures with them?

MM: The Silver Swan was a German restaurant in NYC that hosted a trans party on Saturday nights. This was after Giuliani had closed all the sex clubs, and it became pretty big because there was basically nowhere else left to go. Ina, the organizer, would walk around with a blue flashlight and shine it on anyone doing anything remotely illicit. If she didn’t keep it tame, some undercover cop would get her party shut down, which NYPD had done just about everywhere else. Much of the scene at the Silver Swan was middle-aged and older. I met so many amazing people there. Some were veterans of the Stonewall riots. Mother Flawless Sabrina, an icon from the scene, once showed me portraits Diane Arbus made of her back in the sixties. Georgina was a regular and would start her Saturdays at the Silver Swan, then bring a core group of friends and the men they’d met back to her apartment. Those were the “anything-goes” parties and they would last well into Sunday morning. She would joke that her dog, Gigi, made the guest list. Because Georgina would present as a man during the week for her family and work, the weekend was everything for her. Her longtime partner and many of her friends had died from AIDS a decade earlier. The wild promiscuity that had been so much of her life when she was first welcomed into the trans scene was being increasingly criminalized, even as LBGT rights started to gain more traction. All of her favorite places were closed, so she made her apartment a sanctuary where her community was free to explore their sexual identity. Georgina invited me to photograph her world and we became close friends. Her place had a kind of a magic energy. There were dolls and mirrors everywhere and this big vaginal painting. Different men would come through all night. I’d have fascinating conversations with very open and unique people. I’m drawn to communities that form outside the dominant structures of our society. There’s a kind of liberation that comes from that rejection, which can sometimes manifest in a specific space like Gigi’s.

ME: Growing up I was always told, “To whom much is given, much is expected.” It’s clear that you build tremendous trust and mutual respect with the people you photograph. Otherwise, these people wouldn’t share their most vulnerable moments with you. What are some of the challenges or compromises you have to make as a result of your unflinching photographic approach?

MM: I like that saying a lot. To operate on the basis of mutual respect means sometimes not taking pictures, and sometimes not showing pictures. Consent is really important. I always ask permission to take a photo and I always respect when someone doesn’t want to be photographed, no matter how interesting or beautiful that moment might be. This foundation of respect and empathy is necessary to grow a friendship. I spend a lot of time not doing all that much actual shooting. As the relationship develops, people start to see their lives as something worth documenting, and even if they’re dealing with stigmatized struggles like addiction, they want me there. That’s the “much is given” part, because they’re giving me access to capture intimate moments in their lives. The “much is expected” part has to do with how I show the photos. When someone gives me this access, they put a ton of faith in me, and I want to represent them honestly, while still preserving their dignity. Context is so important and it’s hard to control that when you publish.

ME: Quintessential ‘Matt Mimiaga photos’ seem to have a feeling of complete spontaneity, visually sophisticated, color-driven compositions, and describe a moment of heightened emotional experience within the lives of those you photograph. How do you define a successful photograph within a particular project and within your work overall?

MM: This is hard for me to say, exactly. I’m glad to hear there are identifiable aspects that you see in my work. I think it’s difficult to have a unique voice as a photographer without relying on some sort of trick, which I try to avoid. I’ve simplified my technical process so that the focus is on what you see more than how it’s shown. I try not to predetermine what I’m doing exactly and let the project develop on its own. After photographing someone over time, the picture taking becomes more collaborative. I’m brought to places, introduced to people, and shown things that hold significance in someone’s life. I have all these mantras in my head when I’m shooting: follow the light, capture the beautiful surreal world, make eye contact, document belongings, living spaces, tattoos, outfits, etc. When I’m editing I’m mostly just looking for intimacy.

ME: You’ve done a number of projects following those earlier pictures; The Road, Dirty Kids, and The One Way, to name a few. How do you find your projects and how long do they typically last? What threads or overarching themes do you feel tie all of these projects together?

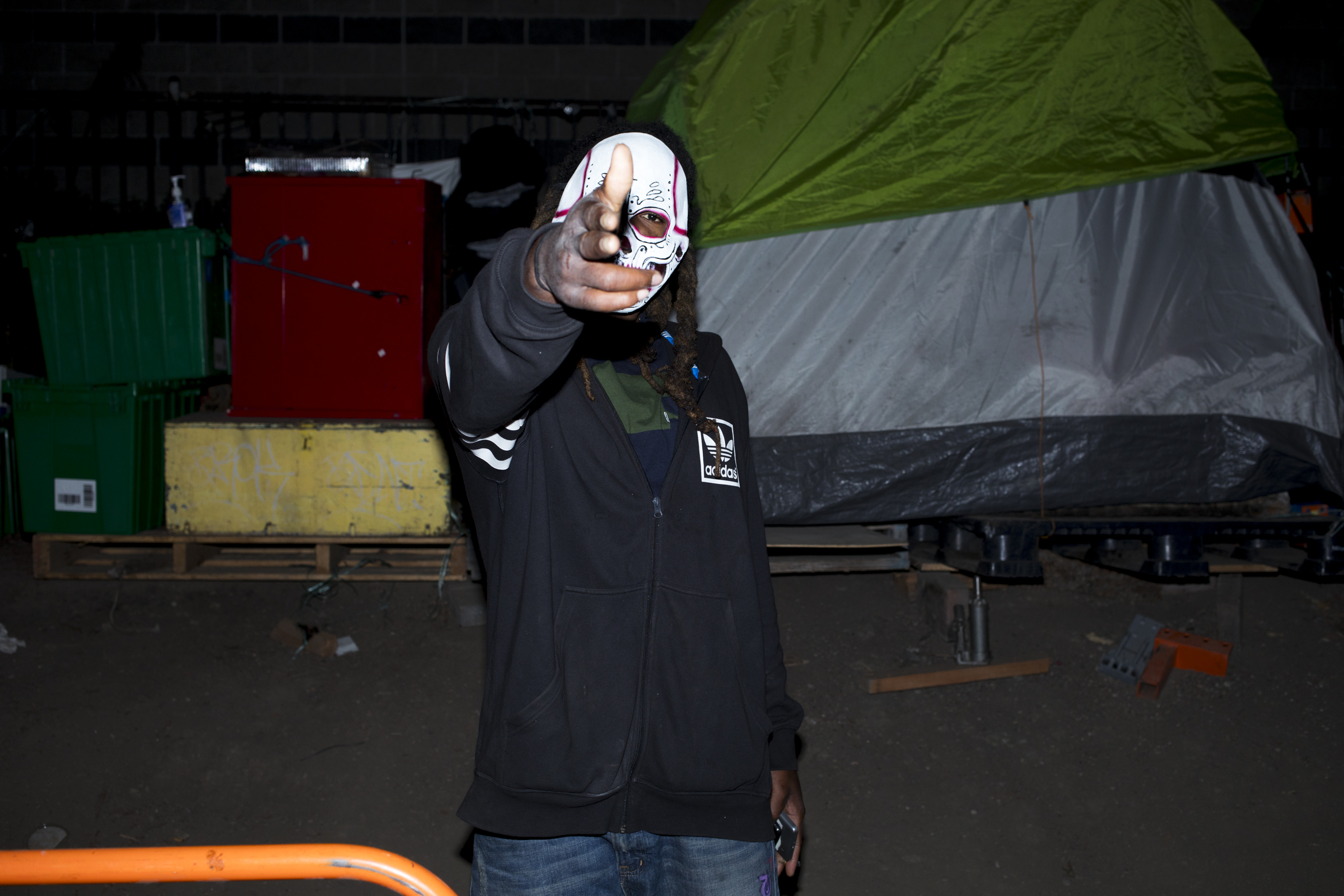

MM: Dirty Kids and The Road came from the same body of work. In 2009 my grandma gave me her 1985 Honda Civic wagon. I flew to LA and drove it back to Brooklyn, where I was living at the time. I gave myself a few weeks to make the trip, and I did my best to meet and photograph people everywhere I went. This was about a year after the 2008 economic crash, and you were seeing foreclosures everywhere. One of the first hobos I met had been a manager at Taco Bell and every other fast food restaurant in his hometown. He just got fed up with working all the time and getting nowhere. It’s strange to think of this as a radical act; traveling on freight trains and sleeping outside instead of working and paying rent. Similar to Georgina’s scene, there’s a kind of liberation that comes from rejecting social norms and forming your own tribe. I ended up driving cross country three more times over the next couple years. When I’m shooting, I meet new people through friends I’ve made and I follow that access wherever it takes me. I met Saydee, and she had friends everywhere. In 2016, Saydee came to the Bay Area for a funeral for her ex-lover who had died from overdose. She ended up staying in Oakland and living in a few encampments, first on Wood Street and then on the One Way, where I’ve been photographing for the past two years. A lot of the people from these projects have died from overdose. For the first time in America since the Spanish flu epidemic, young people have a lower life expectancy than their parents. This is directly related to a rise in overdose and suicide, signaling widespread desperation, poverty, and addiction, all with basically no real ladder out. I want these photos to humanize unhoused communities and highlight harm reduction approaches to addiction, while also capturing the surreal anxiety and beautiful intimacy of life on the street.

Danny with a broken ukulele. He was found dead on the One Way this past June. © Matt Mimiaga, From the series The One Way, 2018

ME: You’re currently working on a multi-generational, character-driven series that is tentatively titled The A.V. What can you share about the lives of those you are photographing, how you identify and maintain that project’s focus, and why you’ve not yet released more of these pictures?

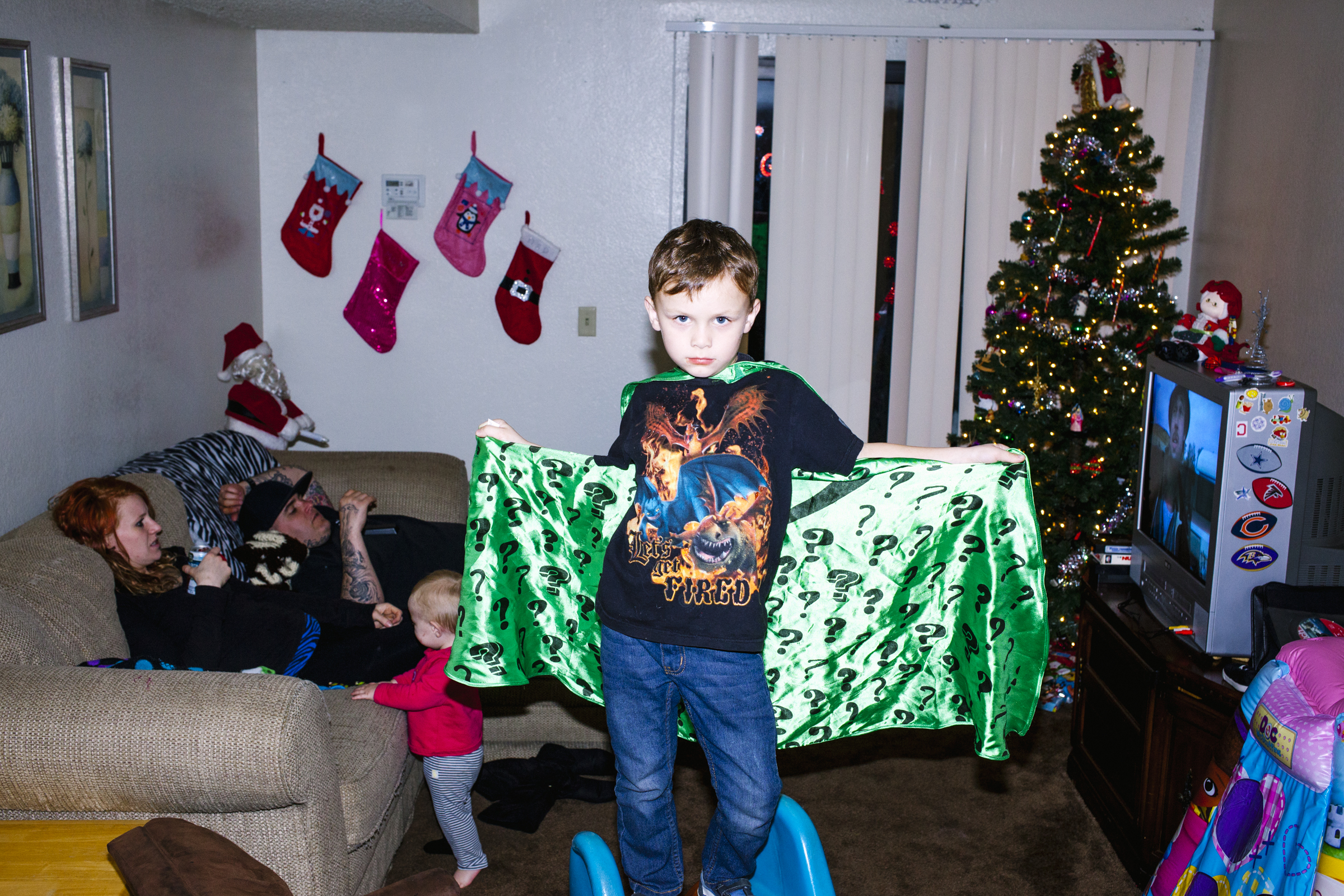

MM: The Antelope Valley is in the high desert, an hour northeast of Los Angeles. There’s a big aviation industry where military contractors like Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman all have factories. Like much of America, the area is experiencing downward working-class mobility. For the past five years, I’ve been following the lives of several people in the A.V. Broadly, the work is about families caught in cycles of addiction, incarceration, and domestic violence. It deals with toxic masculinity and racist ideology, but also the support networks that disenfranchised communities build to survive. I’m reluctant to publish at this time, because I don’t want to negatively impact the lives of the people I’m photographing.

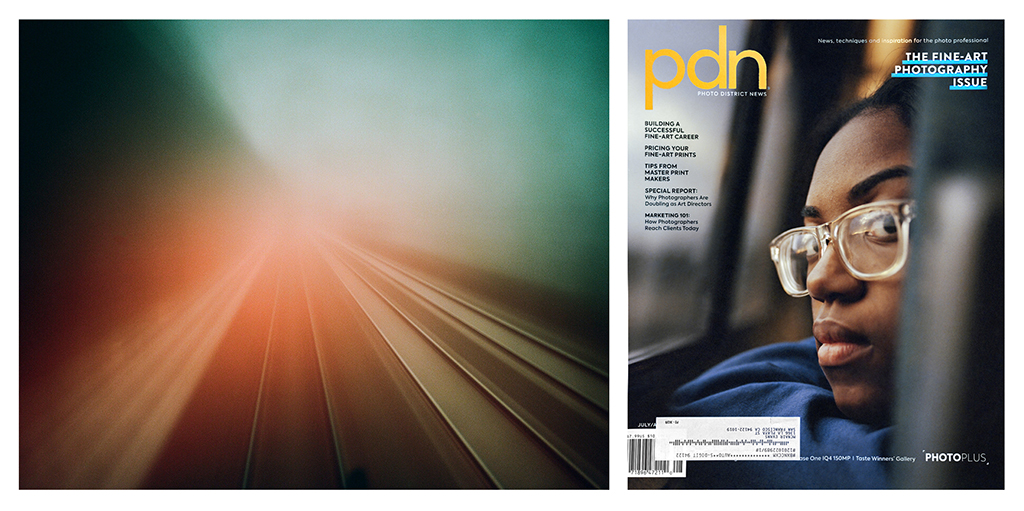

ME: We work in a photographic era of hyper-publication. From social media to the publishing of monographs for every project a photographer completes, much more personal work is being shared than ever before. How essential is exhibiting and / or publishing to your purpose as a photographer?

MM: I don’t feel particularly pressured to publish constantly. I haven’t figured out how to rely on my personal projects as a source of income, so I shoot when I can while assisting commercial photographers for money. Because I usually feel like whatever project I’m working on is still developing and because the pictures seem to gain significance with the passage of time, I just keep shooting. I go through a process of repeated failure in order to get to something I feel is successful. I trust my instincts and keep chipping away. I find it hard to determine when something’s finished. I have a website and Instagram, but I rarely update them. I want to publish books. I think that’s the best way to experience photography.

Campy Duke’s arm is scarred from multiple infections. © Matt Mimiaga, From the series The One Way, 2018

Michele with her sons Eman and CJ. CJ bought everyone matching white pants. He died from overdose earlier this year. © Matt Mimiaga, From the series The One Way, 2018

ME: You’ve spent a lot of time with Joseph Rodriguez, and your impersonations of his life lessons are impeccable. The last time we hung out you were imparting his wisdom of always keeping something cold to drink, other than beer, for when people come over. What’s the best piece of advice he ever gave you?

MM: Earlier I mentioned Joe’s approach— to cultivate close relationships in order to capture intimacy in underrepresented and marginalized communities. That’s the most important lesson. As for advice, I don’t know if this story exactly qualifies, and I’m almost definitely mis-remembering the details, but when Joe was just discovering photography he was working at a commercial printing place and ended up delivering some posters to Larry Clark. Joe took the opportunity to tell Larry that he loved his work, and that he had a similar background— abuse, addiction, incarceration (Joseph Rodriguez’s, Juvenile, goes into those harrowing details), and when Joe started talking about how he wanted to be a photographer Larry said, “then go take some pictures.” So Joe quit his job, enrolled in ICP, paid his way by driving a taxi, and made his incredible book, Spanish Harlem. Joe would say, “you gotta put in the work.”

McNair Evans grew up in a small farming town in North Carolina and found photography while studying cultural anthropology at Davidson College. His photographs explore an American cultural landscape ever-changing with the forces of modernization and focus on individuals impacted by those forces. McNair is a nationally exhibited artist, an active guest lecturer at universities and institutions nationwide, and represented by commercial galleries in San Francisco and Asheville, NC.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi NguyễnDecember 8th, 2025

-

Linda Foard Roberts: LamentNovember 25th, 2025

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025