Photographers on Photographers: Rana Young and Rebecca Drolen

This month, we feature our annual August project, Photographers on Photographers, where visual artists interview colleagues they admire. Thank you to all who have participated for their time, energies and for efforts. Today we are happy to share this interview with Rana Young‘s interview with Rebecca Drolen. – Aline Smithson and Brennan Booker

I first met Rebecca Drolen in Philadelphia at the SPE National Conference in March 2018. An especially nervous introduction, as my partner Zora J Murff and I were interviewing for academic appointments for the upcoming year — her program at the University of Arkansas being one in which Zora became a finalist. Admittedly a little tipsy, amidst the scurrying of people hustling around an open portfolio walk, we approached her to formally introduce ourselves. I remember feeling at ease immediately; there was a calmness in her demeanor and language. Simply, she was cool and I was selfishly happy to like someone as much as I already did their work. As we walked away, he and I looked at each other with eyes that could only be saying, “damn, it’d be sweet to work with her someday.” Luckily for us, just that happened.

Rebecca’s photographs present a space in which I’m able to redefine my reality. A humorous and safe shelter where I have the freedom to evaluate my body, my history, and the space I take-up on my terms. Her preceding bodies of work, Particular Histories and Hair Pieces, together with Factory (in-progress), offer perspective on distilling to the exacting ideology in which our Patriarchal society incubates womxn’s narratives and assigns value to womxn’s bodies. In Factory, I no longer have only the private space to study myself, but a collaborative one submerged in solaced energy. In either viewing Rebecca’s work or hanging with her I know I’m in good company — with many more giggles to come. It is my pleasure to share her imagery and practice insights.

Rebecca Drolen (b. 1983) is an artist and educator working in Arkansas. Her photographs are concerned with how individuals visually assemble their identity – and she is particularly preoccupied with hair. Her work balances built spaces, assemblage and performance, but the end result is persistently the photograph. Drolen’s work has been shown in group and solo exhibitions on a national and international level, within noteworthy venues such as the Huffington Post, Oxford American’s “Eyes on the South,” the Light Factory, the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, The Oklahoma State Museum of Art, and the CICA Museum in Gimpo, Korea. Drolen has had work published in numerous art magazines and blogs and has photographs held in various private collections as well as the permanent collection at McNeese State University. Drolen received her MFA in Photography in 2009 from Indiana University. She is an Assistant Professor and Area Head of Photography at the University of Arkansas.

Rana Young (b. 1983) is an artist and educator based in Faye7eville, Arkansas. Rana holds an MFA in Studio Art from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln where she was an Othmer Fellow and a BFA in Studio Art from Portland State University. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, as well as published online by PDN, Hyperallergic, VICE, Huffington Post, British Journal of Photography, The Wall Street Journal, and The New York Times, among others. Rana launched PHOTO–EMPHASIS, an online platform for highlighting contemporary works made by photography educators, students, and practitioners, with Alec Kaus in June 2017. In collaboration with Kris Graves Projects, she released her first monograph, The Rug’s Topography, in January 2019. Rana currently teaches in the School of Art at the University of Arkansas.

Factory

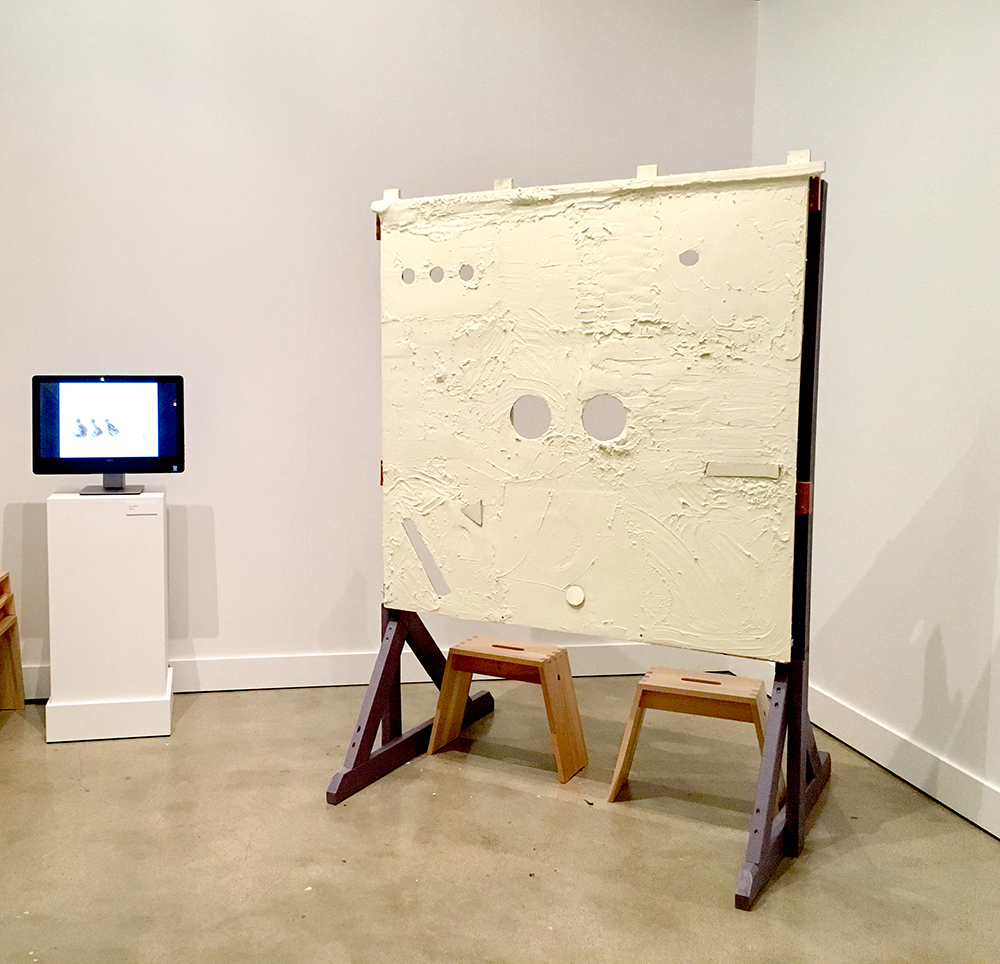

Factory presents a space where the female body is increased as a means of defense and empowerment through physicality. Hair, nails, and teeth are added to the body, rather than managed or removed. The sets are built to juxtapose the flesh and vulnerability of the figures with textured, repurposed materials. The spaces appear to be in the state of being built up and changed, just as the body itself is being re-formed and re-identified. The images address the surreal nature of the body at large, constructed appearances, and how our physicality can communicate with others. While the work humorously points at the desperation of how women’s bodies are managed and adjusted, it also imagines how multiple female bodies can work together to build each other up.

I question if patriarchal ideas can be dismantled and power can be regained once a body is no longer required to be smaller, hairless, and inherently vulnerable. The work uses photographs, looped video, and small sculptures to address notions of how the female body can be emboldened, rather than reduced. – Rebecca Drolen

Rana Young: Will you describe when you recognized photography was it — the medium best suited to aid you in articulating your conceptual framework?

Rebecca Drolen: I barely gave other mediums a chance. I was hooked on photography beginning in high school when I took my first darkroom class. I see it in my students now – the darkroom is alchemy, it makes photography physical and emotional (whether its tedium, love, or hate).

It was a perfect storm when social media really found its beginnings around my same moment of high school. I am dating myself here, but I kept a close community of friends on LiveJournal (!) and art and photographs were a part of the social currency. I am still very close with a lot of those friends despite time and physical distance – photography was a connecting device and a way of sharing myself with others. Even then, I recognized photographs to offer the possibility of building an image or persona – focusing on the ideal, the pointed, and the narrative that you wanted to share – and certainly not sharing a complete reality.

I love photography for its ability to bend the truth. Even ‘straight’ images operate within decisions of inclusion and exclusion. While it is a medium that feels like reality or evidence, it must always point back at its operator. I take advantage of photography’s “truthiness” and try to validate impossible scenes with the proof of a photographic record. It is only in the past 5 years or so that I have actually questioned if photography is it. The work that I make has always taken advantage of elements of sculpture, performance, installation, and physical objects. So much labor of building and staging takes place before the shu7er is released that sometimes the act of pressing the bu7on is downright disappointing. It signals the end. The time to tear down and clean up. (This is the emotional side, because I can’t tear myself from the photograph as the end result – a crafted moment of time that would not have happened without having been incited). In some defiance of the photograph, I am currently considering the possibility of live performances in gallery spaces with a cast of women activating sculptural sets and working together on body rituals. This idea of the temporary, momentary action that is not forever pinned down and idealized through photography also has appeal in my practice.

RY: I’m privileged to know that you’re generous with your time, your optimism, your knowledge — to me, your photographs also host this sentiment. You render a space for solidarity, empowerment, and revolution; a space for womxn to build armors from parts of the body we’ve long been told to “appropriately” maintain. How do you approach destabilizing patriarchal ideology through constructing genderediconography on your own terms?

RD: Our current saga of Patriarchy (political and social power being held predominantly by men) is the direct instigation for this project. When one of my friends saw the first piece made for Factory, she said “wow, its Trump-era Becky” – and she was not wrong. After the election and subsequent Women’s March, I felt limited in my access to contribute, but was so inspired by mass dissent from womxn across the country. Making work felt like the only way that I could meaningfully chime in.

I appreciate that you find generosity or hopefulness in the work. There is a joke being made about desperation, but also a possibility being offered up of strength within our bodies, and that womxn can work together to empower one another.

The photographs are more visually confrontational than my previous projects. I feel the need to reject nostalgia in this work and offer up a contemporary way of looking. It is too easy to romanticize the docile woman of the past within ideals of nurturing, sweetness, and quiet strength. In reality, female bodies and health are legislated by men in power. Social messages direct women at a young age to strive to be thinner and democratize their appearance to current ideas of beauty.

I know that my work cannot destabilize the Patriarchy in its own rite, but I hope to poke at what feels ‘normal’ in terms of requirements for womxns’ bodies and attempt to share the actual absurdity of rituals aimed at controlling them. The shared struggle of removing hair that will always grow back (thicker) is up-ended by the possibility of increasing that same hair in order to defend the soft flesh of the body. In this way, the power of rejecting what seems normal and turning the other way is an act of rebellion – a gesture in imagining new rules.

To take a moment to consider the possibility of womxn in political or social power en masse, Matriarchal societies are often characterized by female leaders that embolden others and nurture strength, rather than exert dominance. Unsurprisingly, they are marked by less violence, but they also tend to involve more sex.

RY: In Factory, we encounter both still and moving images — some requiring introspection and others being activated through looping frames. When and why did you decide to incorporate the GIF format into your practice? Ideally, what do you hope it adds to the body of work and the more traditional way of viewing photographs?

RD: The GIFs in Factory serve two purposes: First, to use a contemporary language that is shared, democratic, and often very funny. Stop motion animation within gifs offers the ability to make the impossible happen between still frames and amplify the work’s level of the uncanny.Second, they serve to reference the cyclical nature of body management as well as dissent. They loop continuously, and there is no beginning or end. For example, No shows a finger wagging back and forth and a set of ponytails moving from side to side. Two movements from a classic “tsk tsk” gesture are disembodied and placed side-by-side. The image intends to consider how multiple parts of the body can deny consent. The looped GIF offers a space to discuss the seemingly endless need to define and redefine boundaries.

RY: I’m interested in the overall construction and aesthetic of this project. Can you share a bit about your use of materials, color paleQe, props, and design principles? Why build sets?

RD: I build sets to distinguish these stories from specific histories and knowable locations. The places that I am creating often represent a “third space” that is separate from reality and offers distinct opportunities for the bodies involved. The surfaces are all common building materials – wood, plaster, paint, ceiling tiles, etc. – but they reference skin in their marks, movements, and color. When I was a new mother, I had long, wakeful nights and watched a lot of home renovation shows. Everyone’s first move was to scrape away the popcorn ceilings! Most of my adult homes have had popcorn ceilings, and I have learned that it is clearly used as a material to cover flaws or previous wounds to the surface. I like to imbue my built spaces with a sense of previous use and history. Many of the surfaces show spaces painted over that may imply that it has been used for a specific purpose for a long time, freshened up with paint, and used again. The spaces seem built and adjusted to suit the task at hand.

I keep a general inventory of props related to the body – wigs, fake nails, makeup, pantyhose, etc. The project relies just as heavily on the cosmetics aisle as it does on the hardware store. The props are narrative devices, sources of activity, and ways of transforming the body. I often use props in a way that subverts their original beauty purpose. For example, Mustache uses a row of false eyelashes to build an abstract mustache between the nose and red lips.

The holes are like a game – the body reaches through to perform a task leaving the viewer with the knowledge that more is happening behind the scenes than they are able to access. This curiosity is amplified by the body feeling very unfamiliar – compositions defy usual voyeuristic views of womxn’s bodies by sharing parts of the body that cannot be re-aligned logically and demanding a7ention to their purposeful actions.

RY: Let’s get behind the scenes. Will you outline how you make a piece for this series, start to finish?

RD: I usually begin with listing ideas as a means of keeping a loose inventory of possibilities – not all ideas are acted upon. Currently my dry erase board in the studio says: fake tan, oversized brows, ears listening, and noses smelling. Inspiring! It is also critical that I read, research, and absorb stories, media, histories and politics related to female identity and experience. From the lists, I make very basic sketches to consider how the narrative could play out within a rectangle. From sketches I start to gather materials, plan spaces, and build. I use very base level materials – sometimes cardboard and foam, other times more sturdy wood. Building for the camera means it only has to be standing as long as it takes to make the picture, and it only has to look correct from one distinct point of view. I take a lot of liberties with this freedom – most of my spaces lack any structural integrity and are clamped together or leaned into place.

Much of this work relies on self-portraiture, but I use models sometimes. In either situation, I make a lot of possible photographs of gestures and movements of the body. I practice and run back and forth between the camera and the set. It is a very physical process.

I usually leave the sets in place until I finish editing the photographs, just in case I need to re-shoot an element. After that, I tear them down and decide if they can be re-used or should be thrown out. I have trouble throwing things out, and my studio is persistently messy.

RY: Self-portraiture has become a staple of your practice and throughout your series’ you unpack prescribed notions regarding body ideals — at times, even through a blatantly ludicrous lens. How does humor function as a component in your imagery? How do you approach performing as both subject and maker?

RD: Humor is a powerful communicator. Difficult subjects can be addressed with a greater sense of ease when you are able to laugh about them. I often use my own body as the target of the joke but intend to be a stand-in for others to recognize a larger shared absurdity. Many pieces can be funny on the surface level, but I hope that there is a larger question being asked that sits beneath the humor.

With the knowledge that the joke is often on me, it is easy to discuss the self-portrait as important to the work, but it also adds an increased struggle as an impractical exercise. To be both subject and photographer has its obvious complications – I can’t look through the lens – something that seems like a basic human right in photography. It can also be physically challenging. There are scenes that are either impossible or unsafe to set a timer and run into the space or even to operate a remote. I usually seek out someone to press the bu7on for me in those scenarios – at times making my partner into a very reluctant photographer.

Despite these drawbacks, I was drawn to self-portraiture very early in my practice for all that it has to offer: control over an idea, the potential to create a consistent character, and, of course, the ability to work alone (with a willing model at any hour of the day). I do not approach self-portraiture as an offering of my specific personal history, but rather, I use my body as a stand-in to begin a conversation that I am curious about. Self-portraiture is no longer a rule in the work, and I am beginning to question how using models can broaden the conversation that I am proposing beyond the limitations of my own body and what it is able to represent.

RY: As a mother, what do you hope your daughter learns about this moment, years from now, from viewing your work as a cultural document? How does she react to them now?

RD: I hope that my daughter is able to look back at this moment and see it as a time of protest and growth (you said I was an optimist earlier!). It is an overwhelming, discouraging political moment characterized not just by inequality, but also abuse to human rights. Resistance has been a necessary, on-going means of connection – opening dialogues of dissent. I am heartened by the response of the Women’s March, the growing understanding of human sexuality as a spectrum, and the checking and questioning of patriarchal power within the #metoo movement. These are all actions that make space for someone like my daughter and seem to chip away at monolithic power.

At the age of four, my daughter is already much more forceful, unencumbered, and driven than myself, and while it is exhausting at times, I desperately want to protect these qualities in her. I hope that her status as a womxn will not equate to weakness in her generation, and I hope that she will have the freedom to explore her gender identity so that her femininity is more complex than a simple rejection of masculinity. Artwork should never be completely divorced from its social or political context, and I hope that my daughter recognizes the pictures in correlation to the political provocation that incited them. Right now, she thinks the work is funny and shouts things like “mom’s no-no finger!” The candy colors get her excited, and she is endlessly curious about bodies in general. For now, that is enough! She had a guest appearance on Vulnerable Parts as the butt in the bottom center. She usually is proud of that, but we might have to ask her again as a teenager.

RY: Last question. Where might one locate said Factory?

RD: Somewhere in my mind. In my studio. Hopefully in a gallery near you.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025