Photographers on Photographers: Shawn Bush on Drew Nikonowicz

Drew Nikonowicz (born in St. Louis Missouri, 1993) earned a BFA degree from the University of Missouri – Columbia in 2016. His work employs analog photographic processes as well as computer simulations to deal with exploration and experience in contemporary culture. He has exhibited both nationally and internationally. In 2015 he received the Aperture Portfolio Prize and the Lenscratch Student Prize. In 2017 Nikonowicz completed a one-year residency at Fabrica Research Centre.

He now lives and works in the United States in Saint Louis, Missouri as an artist and owner of the company Standard Cameras. His first photobook, This World and Others Like It, was co-published by Yoffy Press and FW:Books in 2019.

Lens based artist Shawn Bush grew up in Detroit MI, a city whose civic history and geographic location has profoundly influenced the way he thinks about space within the American sociopolitical landscape. He is interested in over-built systems, failing icons and crumbled mythologies. Bush earned an MFA in Photography from the Rhode Island School of Design and BFA in Photography from Columbia College Chicago. He is the recipient of the 2016 T.C Colley grant for excellence in lens-based media and the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize winner. His debut artist book A Golden State won first prize in the handmade category at the 2016 Lucie Photobook Prize in New York City and is included in several noted collections, including the Griffin Museum of Photography in Boston, MA and Benaki Museum in Athens, Greece. A Golden State was published by Skylark Editions in 2018. Bush is the owner of Dais Books and Associate Professor of Photography at Casper College.

Lens based artist Shawn Bush grew up in Detroit MI, a city whose civic history and geographic location has profoundly influenced the way he thinks about space within the American sociopolitical landscape. He is interested in over-built systems, failing icons and crumbled mythologies. Bush earned an MFA in Photography from the Rhode Island School of Design and BFA in Photography from Columbia College Chicago. He is the recipient of the 2016 T.C Colley grant for excellence in lens-based media and the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize winner. His debut artist book A Golden State won first prize in the handmade category at the 2016 Lucie Photobook Prize in New York City and is included in several noted collections, including the Griffin Museum of Photography in Boston, MA and Benaki Museum in Athens, Greece. A Golden State was published by Skylark Editions in 2018. Bush is the owner of Dais Books and Associate Professor of Photography at Casper College.

This World and Others Like It

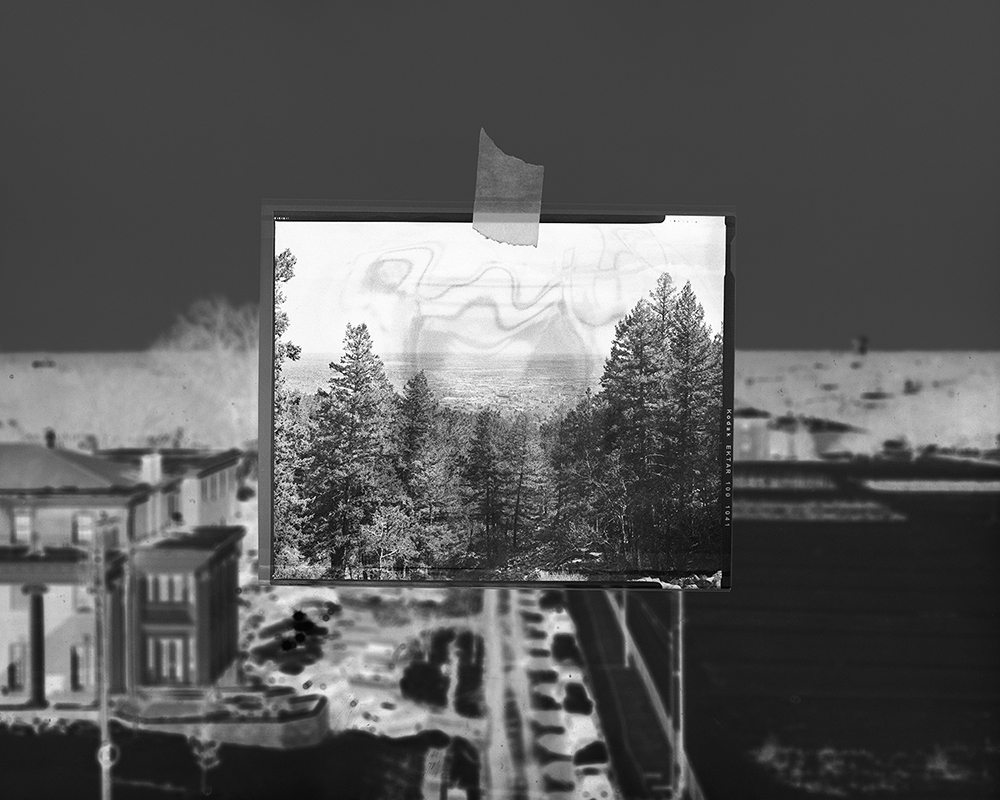

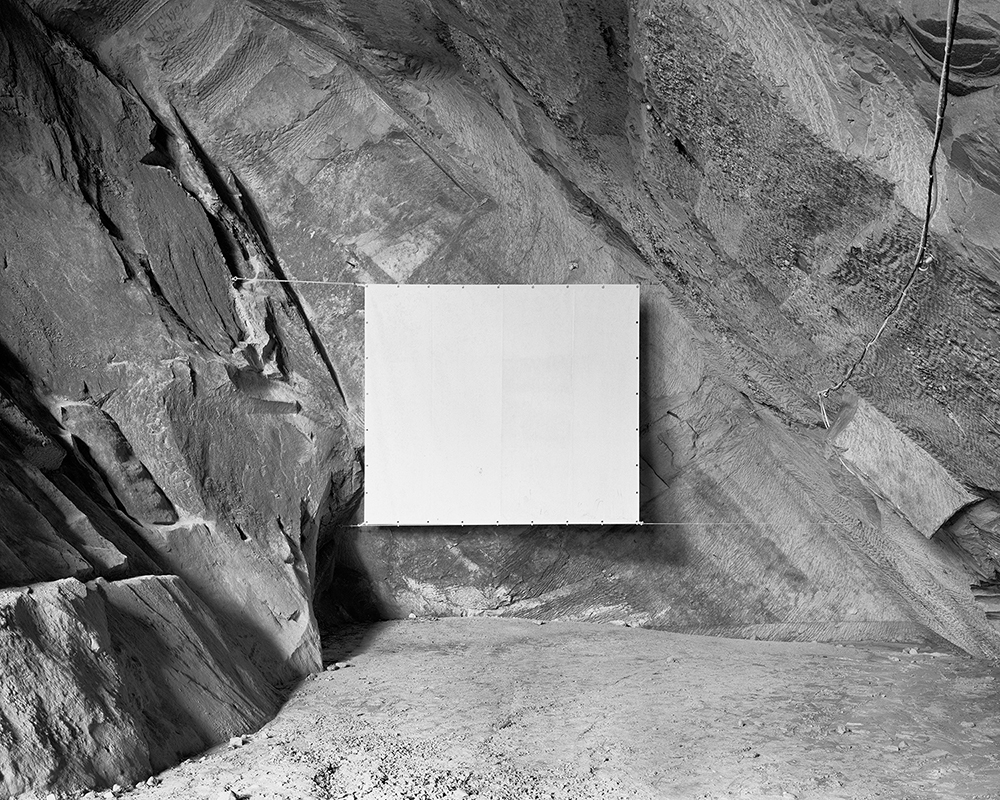

This World and Others Like It investigates the role of the 21st century explorer by combining computer modeling with analogue photographic processes. Drawing upon the language of 19th Century survey images, I question their relationship with current methods of record making.

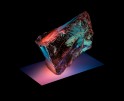

Thousands of explorable realities exist through rover and probe based imagery, virtual role-playing, and video game software. Within the contemporary wilderness, robots have replaced photographers as mediators producing images completely dislocated from human experience. This suggests that now the sublime landscape is only accessible through the boundaries of technology.

Shawn Bush: What are your interests juxtaposing analog large format photography and digital compositions in This World and Others Like It? Could that be a product of your personal interests outside of art, age and/or exposure to digital universes?

Drew Nikonowicz: The bulk of This World and Others Like It was made during my time as a student pursuing my BFA degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia. Especially in my photography courses, there was an emphasis on utilizing all the tools in your toolkit. As a result I felt very comfortable experimenting, and eventually it led to a project that had both analog photographs and computer generated photographs in it.

I grew up alongside the internet, which distilled a deep desire to explore the worlds at my fingertips. I was constantly moving in and out of tangible and virtual spaces. One moment I might be playing a video game, and then I would be off to hockey practice or to ride my bike. Because I have never lived without an internet connection, I have a very comfortable relationship to technology. The project is definitely a product of my personal interests in gaming, exploring and technology – especially through photography.

SB: In a physical world that has an increasing presence of alternate digital realities, do you see either method of creation, digital construction or analog photographic processes, as a more truthful representation of the world?

DN: They both suffer from the same problems. Someone – or something – is still making the decisions, and we rarely have access to these decisions. So regardless of whether it’s a computer generated photograph or an analog photograph, the edges of the frame and the content of the image are selected long before we see it. I think it is what different image-making apparatuses have in common that make them exciting, and I don’t think either kind is more or less accurate. Compared to analog photography, newer technology is much more volatile and dangerous though. It’s outside the scope of this conversation, but with new advancements in things like Deep Fakes and other artificial intelligences, image making technology is only

becoming more autonomous and dangerous.

SB: You recently started your own company, Standard Cameras. Congratulations on that! Were you using prototypes of the Standard Camera while making photos for This World and Others Like It?

DN: Thank you! It has been an extremely exciting and time-consuming experience. None of the images in This World and Others Like It were made with one of my 4×5 prototypes, however there are little hints of the camera around the work – especially in project outtakes. I began designing the camera as a side project in 2014, which was right around the time I was really finding momentum with This World and Others Like It. The act of building a camera felt very related to my image-making practice, and they often went hand in hand. So unfortunately, I was not using it to make work for the project. I do believe it was and is an important part of my practice though.

SB: Many of the images use the language of scientific or survey photography, including your deadpan gaze at objects or scenery and use of flash. What was your inspiration in using such a methodology? Did you comprise a formula or parameters for yourself to work within while making This World and Others Like It?

DN: I always try to be a very omnivorous photographer, both in technique and content. This was especially easy to commit to while I was still studying, because as a student you are constantly exposed to new techniques, artists, and ideas. There wasn’t really a formula or set of parameters for making work, other than to try every idea I had. This is still true. With this strategy it does take a bit longer to gain momentum in the beginning of a project though.

I did my best to tap into those languages to create an antiseptic, but excited, approach to image-making. Especially considering the project’s interest in questioning how, in the 21st century, we explore the worlds around us, it felt important to tap into the language of survey photography. The computer generated photographs are especially related. I am showing images of worlds that only briefly existed on my computer – a survey of the digital universe. The same could be said about rover and probe based photographs like NASA’s Curiosity Rover. We can only access these places through our computers.

SB: In another interview about this work, you mentioned you use photography “to satisfy a desire to understand things around you through the process of deconstruction”. Are the digital constructions a means of reverse engineering the methods in which we experience images or do they serve a completely different purpose within your artistic process?

DN: This World and Others Like It is very much an exploration of how we experience the world around us through images. Both the analog photographs and the computer generated photographs are an attempt to deconstruct the image-making and viewing apparatus. By thinking about photographs as constructed experiences, we can connect them to a larger history. Just like a paved trail in a park teaches you how to see the forest, a photograph teaches you how to see the image. So the computer generated photographs – especially the ones where I have left in ‘failures’ – attempt to contribute to this same conversation.

SB: Where do you source the composite images from? Are they entirely created from appropriated imagery or do you combine your own photographs with those that are found?

DN: There are no actual composites in the project. There are definitely photographs of other photographs, and in-frame constructions occurring, but never in post production. So all of the source imagery and content is either line of sight or my own fabrication. One way I rephotograph the world is by photographing my computer screen – which happens several times throughout the project. I use a lot of layering of surfaces and images on top of images to create a sense of distance between the viewer and the photograph’s subject.

SB: In This World and Others Like It an iconic image of the first moon landing is used, marking an exploration into an unknown void as a part of a collective sub-reality. What is your interest in using imagery that has been widely distributed and seen rather than electing to use images that weren’t distributed in such a capacity?

DN: In that case, I was interested in properly recontextualizing the image to fit into the 21st century. I did not see Apollo 11 occur first hand – I only have access to the experience due to NASA putting their archives online. So I rephotographed Buzz Aldrin on the moon on my computer screen as a way to bring the image into the 21st century. The choice to use a famous image over a lesser known image helps this goal. The grid of pixels is embedded in the surface of the image. With such a well known image, we have clear expectations of what we will find when we look closely. These are broken when we realize the image has been filtered through the pixels of a computer screen.

SB: After having massive success with This World and Others Like, including winning the coveted Aperture Portfolio Prize, what are your plans for the near and distant future?

DN: I plan to keep kicking the ball down the road! I am working on exhibiting the work more, giving more lectures, and sharing the book with anyone interested. Especially lectures – I have to admit, I am a huge fan of public speaking. I will also definitely continue to grow and improve Standard Cameras. It’s such a blast to work every day building affordable cameras, but as the company grows I am working on producing more educational content and products for the community to utilize. Of course, I also hope to share my new work with the world very soon. We’ll see when though – my new projects aren’t quite ready to see the light of day yet.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Hugh Kretschmer: Plastic “Waves”April 24th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Richard Lloyd Lewis: Abiogenesis, My Home, Our HomeApril 23rd, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Jason Lindsey in Conversation with Areca RoeApril 21st, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: J Wren Supak in Conversation with Ryan ParkerApril 20th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Josh Hobson in Conversation with Kes EfstathiouApril 19th, 2024