Brittney Denham: The States Project: Wyoming

Brittney Denham was born in California and raised in Wyoming. She graduated from The Ohio State University in 2012 with an MFA. Currently she is Printmaking and Photography Faculty, as well as the Gallery Director at Sheridan College in Sheridan Wyoming. Her work has been exhibited nationally, including most recent North by Northwest, at The Yellowstone Art Museum in Billings Montana, Representing the West: A New Frontier, at Sangre de Cristo Arts Center, Colorado and The Arrival: Work by Brittney Denham, at COS Gallery in Visalia, California.

Thank you for taking the time to speak with me about your work and experiences of being an artist in Wyoming. What got you interested in art, specifically photography?

Thank you reaching out to me. My interest in art started young. The school systems I was brought up in had generous art offerings like ceramics, painting, drawing, even a whole semester devoted to fiber. When I got to high school I enrolled in a photography class. I was extremely lucky, the teacher exposed us to different photographic processes, film, digital, Photoshop, alternative, he even peppered in photo history. That was it for me, I was hooked.

I fell in love with how many different ways there were to visually describe something. I’m always searching for the best process to articulate an idea; therefore, I’m continually learning.

As someone who was born in California and grew up in Wyoming, does the experience of living in two very different places have any effect on your artistic practice? I am new to Wyoming, though from my limited experience, many people here don’t relate to Californian ideologies.

Absolutely! I spent most of my formative years living in Wyoming and spending summers in California or Boston. I later moved to Denver Colorado to attend art school and Columbus Ohio to get my MFA.

Coming from a place that city folks might find remote has led to some polarizing conversations. I got asked as a kid if I rode my horse to school every day, or if we had running water. On the other side of the spectrum, until I moved to the city I never thought it was odd that most people I knew had an animal mounted to living room wall. Moving from place to place gave me an outsiders perspective. I think my upbringing made me more flexible as a maker as well as more susceptible to making work about what I’m encountering in the moment, much like how Western Vestige or This is to tell you we’re out in the Old West was made.

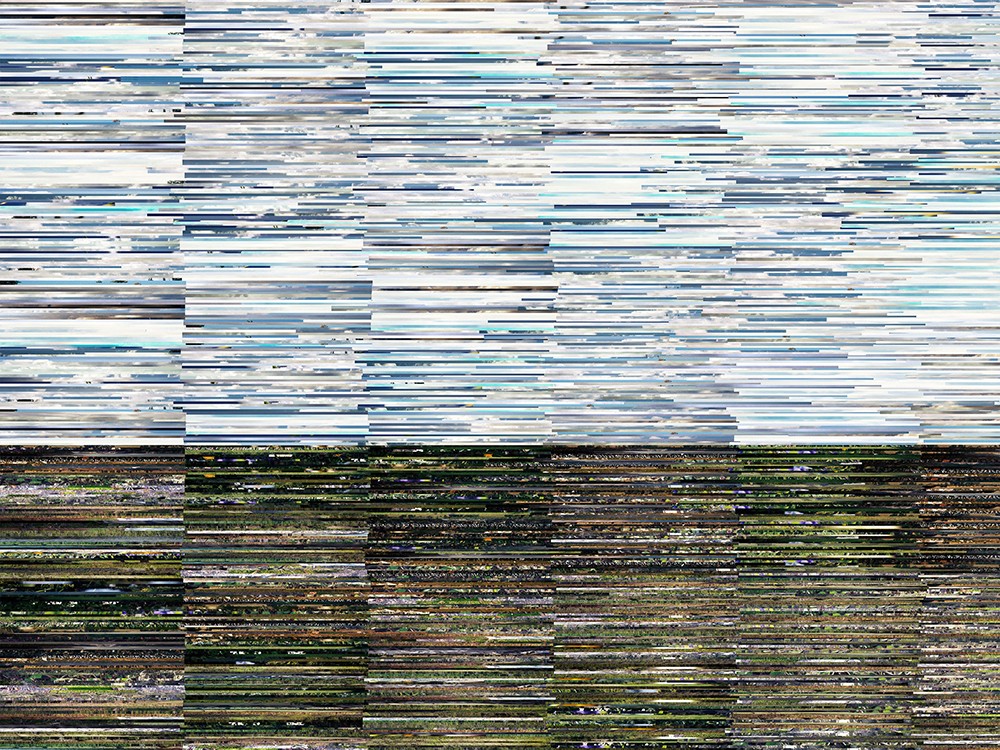

I really enjoy your Western Vestige series and your interpretation on humans/landscape interaction, specifically in national parks which are becoming more and more of a commodity with the advent of social media and the importance for photographic evidence. The juxtaposition between photographs of tourists documenting their immediate and collaged images is fascinating. Can you talk about their relationship? Where are all of the collaged images sourced from?

I had just moved back to Wyoming and was reexamining the landscape as color fields. I was looking at the work of Mark Rothko, as well as Thomas Moran and Albert Bierstadt.

While on my way to Yellowstone National Park I was rereading a Susan Sontag essay where she writes, “A way of certifying experience, taking photographs is also a way of refusing it-by limiting experience to a search for the photogenic, by converting experience into an image, a souvenir. Travel becomes a strategy for accumulating photographs.” All of the research I had done set the stage for how I was going to experience the park… although I didn’t know it at the time.

A couple miles into the park, the car I was in jolted to a standstill by a line of cars. People were leaving their running vehicles to snap a photograph of a family of Bison. A place I believed to be wild, became more like Disney Land. Every stop I made was accompanied by hundreds of people with selfie sticks, go pros, iPads, and iPhones. There was a cadence to how people were experiencing nature, taking a landscape photo, a group shot, and a selfie, then running to the next location. There weren’t a lot of tourists who were looking outside of their screens. I was far away from a Bierstadt painting and found myself wondering what was going to happen to all of the tourist images of the exact same attraction, and what was the point of me taking a replica of everyone else’s photo? The people visiting the park were changing the view.

The collaged images are constructed using original, found, and fellow tourist’s photographs to reconstruct a new landscape.

Your inclination to use “found” images from locations which are relatively familiar to many because of the amount of exposure they receive though various media outlet such as Old Faithful in Yellowstone National Park is fascinating. What is you interest in using appropriated imagery?

I think because I grew up in Wyoming and left, I spent a lot of time explaining to people what Wyoming is. Usually the first couple of things people associate with Wyoming are Yellowstone, cowboys, and Jackson Hole, there is a lot more in between.

I believe I use appropriated imagery like Old Faithful because it’s already charged Iconography. There are already histories and myths attached to them. It’s fun to use imagery that is already culturally saturated and turn it into something else so a viewer could possibly take something new from the work.

As an artist who lives in Wyoming, do you see any common themes within the work made by artists who live here?

I live in a place where Frederic Remington is King.

I suppose it doesn’t really matter if you’re questioning the West like I do, or romanticizing the West, it’s difficult to live in Wyoming and not let the land seep into your artistic practice.

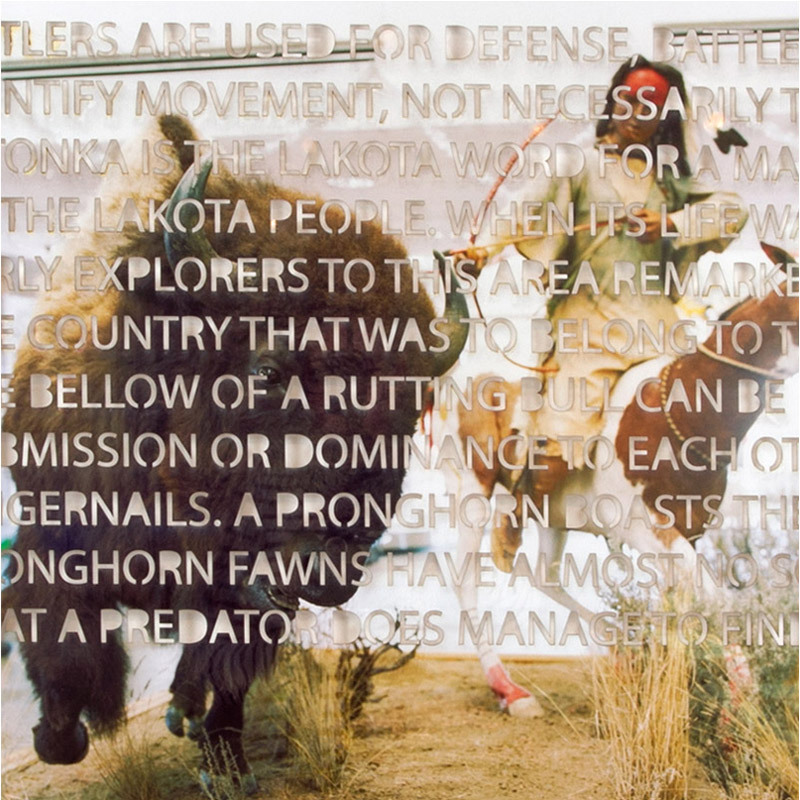

In a few of your series such as Words and “This is to tell you we’re out in the Old West” you elect to include image and text. I am especially intrigued by your play with optics in some images by usage of embossing and laser cutting text into the prints in “This is to tell you we’re out in the Old West”. What was your inclination to use image and text? Do you see the text as descriptions of the images themselves or rather an additional layer of information which complicates the visual imagery?

I’m drawn to using text with imagery because time and time again the 2 fail on their own. The text found in “This is to tell you we’re out in the Old West” comes from literature found around the places the images were taken i.e. tourist pamphlets and postcards. In all of the pieces both the text and photographs have inaccuracies. By embedding the text within the photograph the reader has to decipher what’s more authentic, the photo or words. To answer your question, I see text as an additional layer of information.

In “This is to tell you we’re out in the Old West” you critique the narrow and antiquated definitions of Old Western culture. Many of the images point to common Western American tropes such as buffalo, Native American culture, coal mining trucks and guns. What is your take on the current state of the Old West? Does it exist anymore or is it just a façade of its former self?

Both! I know many cowboys and cowgirls. There is still an Old West code that most Wyoming natives live by, helping your neighbor, having grit, and working hard.

I also think that a lot of Wyoming towns play up the Old West tropes to draw outsiders in and to keep the myths alive. Tourists love feeling like they’re in a John Wayne movie and watching a pretend gun fight on Main Street. The façade and productions are how a lot of small towns in Wyoming survive.

What are your plans for the future? Do you plan to continue creating work about the American West?

At the moment I am making work about motherhood. I’m a new mom, so right now I’m digging through the meaning of that! I have been working with photographic and printmaking techniques, mostly cyanotypes and lithographs.

I once heard Sally Mann say an artist should make work about what they know. I will always be drawn to make work about the American West. It’s what I know, it’s the place I always come back to.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026