Christine Fitzgerald: Trafficked

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Trafficked by Christine Fitzgerald.

Christine Fitzgerald is a photo-based artist from Ottawa, Canada. Christine has always been captivated with nature. Her fascination began in her childhood growing-up in the Eastern Townships of Québec and has never abated. Her work is inspired by hidden histories and often deals with the relationship between humans and the natural environment, and the tension that this relationship inevitably creates.

Christine recognizes the value of historical continuity in the creation of a photograph as an object. This has greatly influenced her artistic practice, as she has increasingly moved to photographic plate/printmaking using obsolete historical processes merged with modern technology. Her university science background coupled with her understanding of the relationship between plate/printmaking and photographic observation, allow her to experiment with chemistry and technology to develop innovative approaches to creating her unique aesthetic to her work.

Christine has degrees from Acadia and Dalhousie Universities, and completed the diploma program at the School of the Photographic Arts: Ottawa. She completed an artist residency at the Ottawa School of Art and was an invited artist in residence in print media, at York University’s School of Arts, Media, Performance and Design. Christine has won numerous awards including the 2016 International Fine Art Photographer of the Year in the International Photography Awards in New York City and was a winner of the 2017 International Julia Margaret Cameron Award for women photographers. She was one of 15 visual artists selected for the historic Canada C3 Expedition on the occasion of Canada’s 150th anniversary. Her work is held in public and private collections, has been showcased in exhibits around the world including Ottawa, Toronto, New York, Los Angeles, Barcelona and London, and has been featured by The Washington Post, National Geographic, Feature Shoot, the CBC, Black+White Photography Magazine UK, Artsfile and PhotoEd Magazine.

Trafficked

“The fascination of the Abomination” – from Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad (1899)

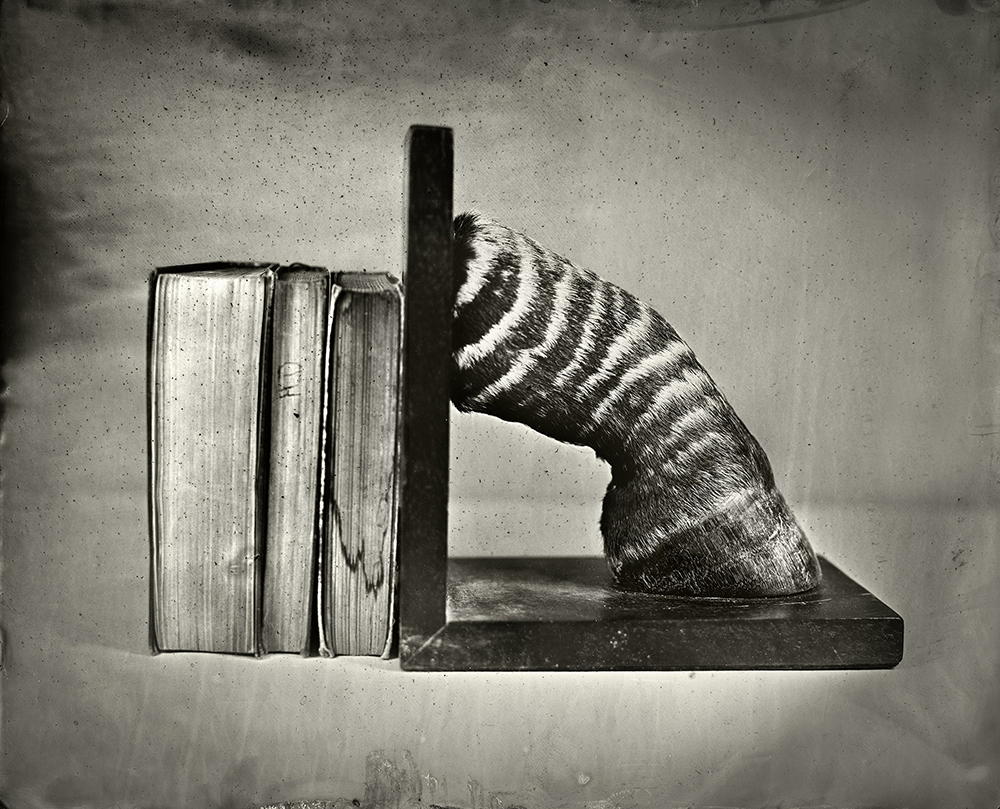

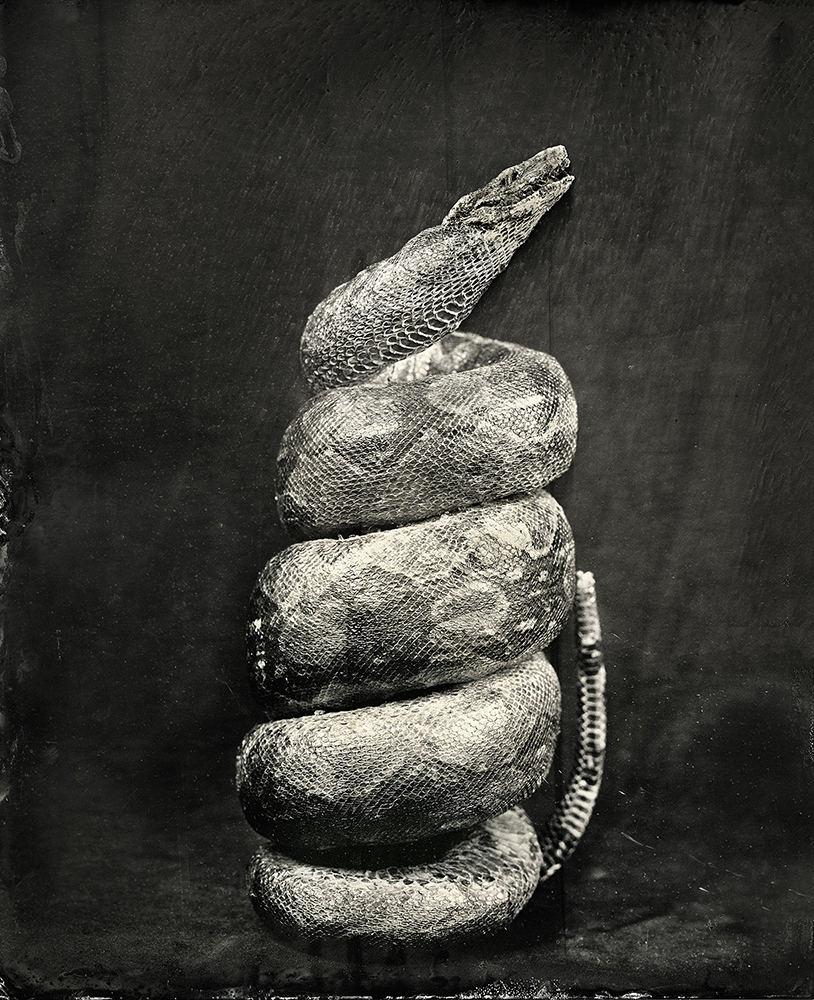

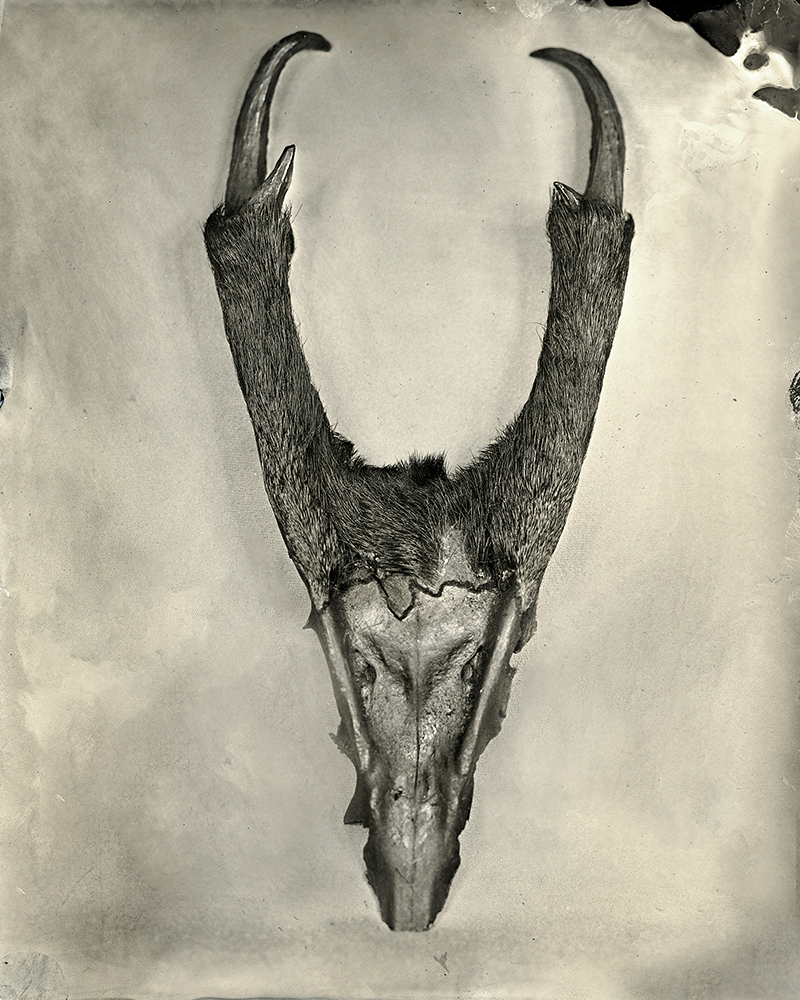

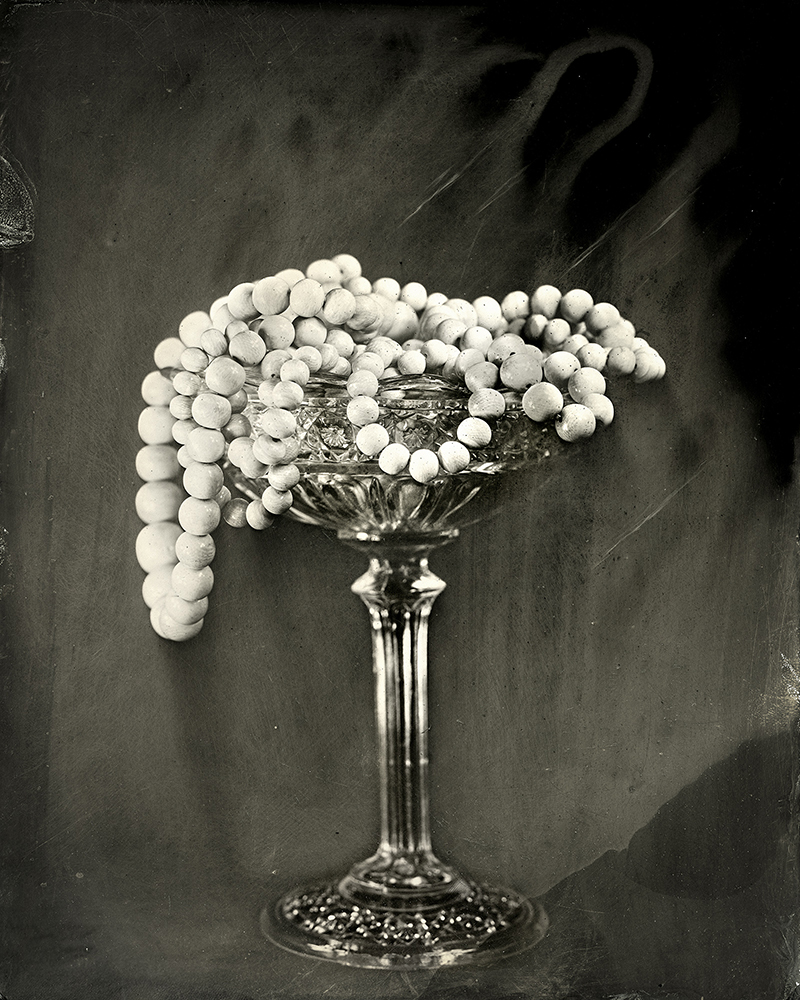

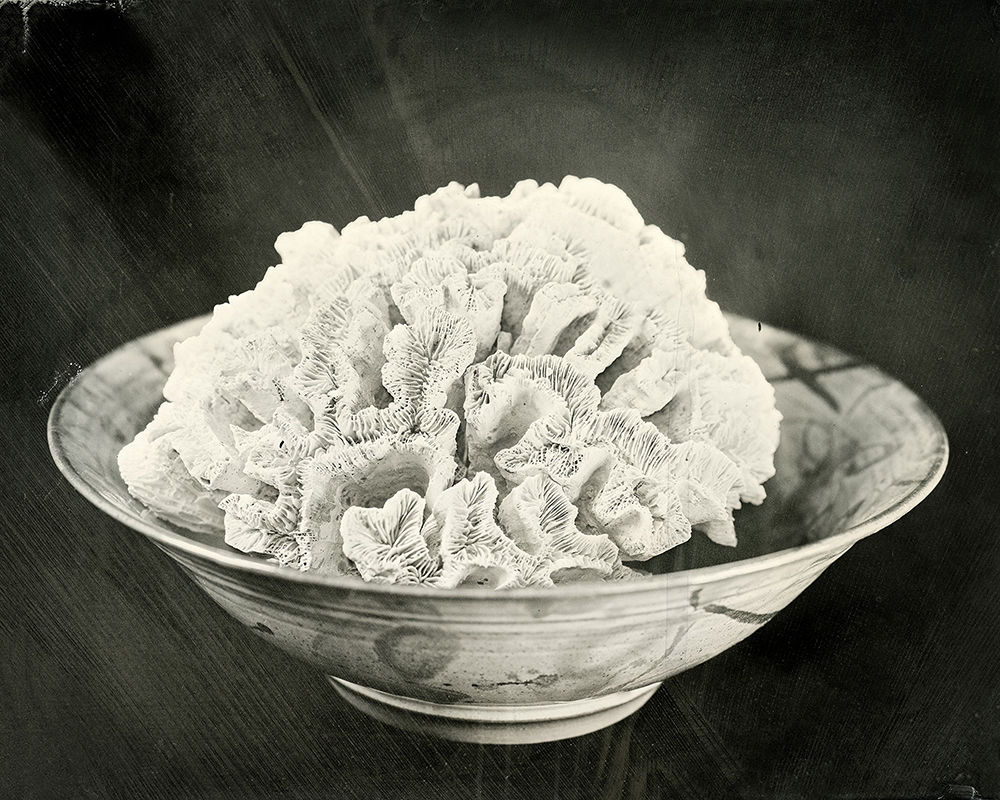

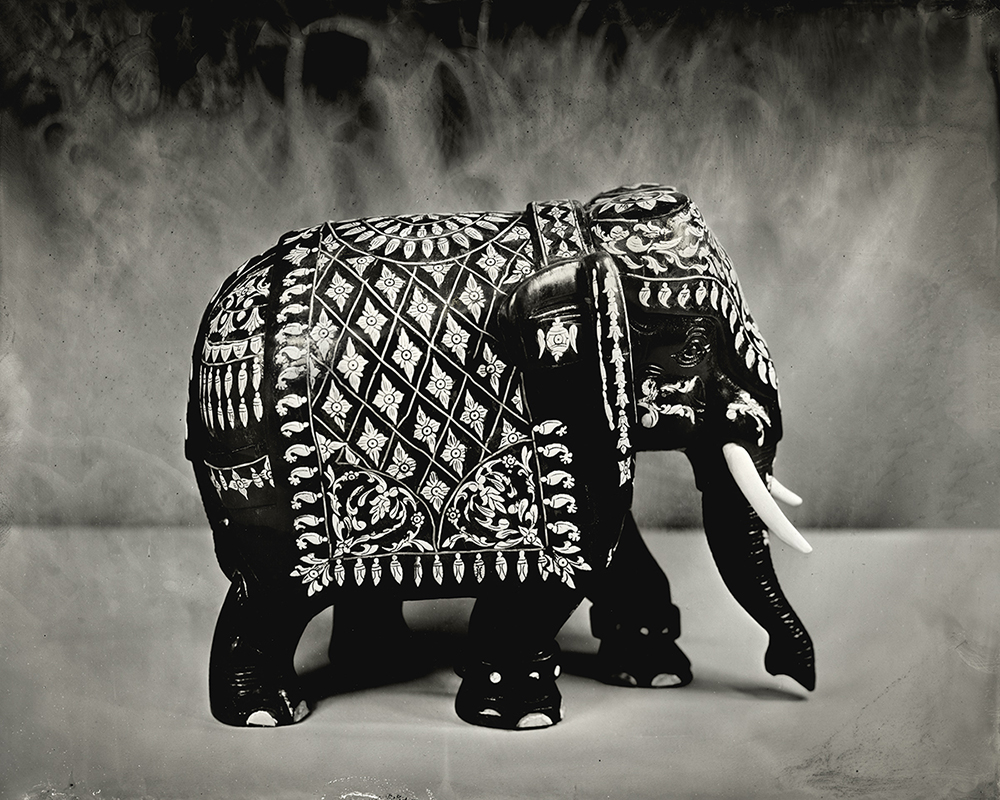

TRAFFICKED presents images of specimens confiscated by the Wildlife Enforcement Branch of the Canadian Government. My intent with this series was to shed light on the disturbing reality of illegal wildlife trade. By portraying the specimens through a series of traditional still life images, I allude to a past when exotic trade was an important part of empire building, linking the subject matter through a contemporary lens.

I wanted to take a different approach to the subject matter. I spent days locked in a secret location with cases of animal parts, trophies and other kinds of confiscated wildlife specimens. I set-up a dark room using a portable fishing tent on site, and captured my images using the 19th century wet collodion photographic process. In addition to the vintage aesthetic of its tonality, the imperfections from the process – some planned and other unplanned – enabled me to underscore humanity’s own imperfections and the impermanence of life. When you spend so much time with these specimens you have a lot of time to reflect on the magnitude of this worldwide issue. The illegal trade of wildlife is horrific. It’s about human greed, ignorance, and indifference.

Daniel George: Describe your general interests in depicting elements of the natural world through photography—since you have completed several bodies of work on the topic.

Christine Fitzgerald: I grew up in a small town in the Province of Québec in Canada and spent most of my childhood playing outdoors. So it is no surprise that most of my inspiration for my work to date has come from the national environment, with underlying themes of impermanence, identity and history.

DG: You spent time locked in a secret location making these photographs. I feel naturally inclined to ask, how did you find out about this place and how did you gain access?

CF: I found out about the work of the Wildlife Enforcement Branch of the Canadian Government from a news story a while back. I was busy working on my Threatened series at the time so I just parked the information in my head for future reference.

The Canadian Wildlife Enforcement Branch is responsible for enforcing laws that protect and conserve wildlife, particularly specimens in trade and migratory birds. The unit has about 80 officers located across the country. The illegal trade of wildlife is a global issue and Canada is certainly not immune to this issue. Canada is a huge country geographically and so these officers have a really tough job. Specimens – especially endangered or protected species – are seized when they are found being smuggled across the Canadian border by air, ship or ground.

A few years ago I saw a photograph in the news of a dead Rhino in Africa with its horn hacked-off by poachers. This photo affected me deeply and so I decided that it was time to do something closer to home about the illegal trafficking of wildlife.

I had coffee with a friend who had worked in the Canadian government and she connected me to the relevant officials. I then had a conference call with the head of the Canadian Wildlife Enforcement Branch and made my pitch for my proposed photographic project. My ‘wish list’ was quite long and included setting up my portable darkroom on site and a makeshift studio with artificial lights, over an extended period of time. I was certain that he would say no but to my great surprised he loved the idea.

Because many of the specimens are valuable on the dark underground market of illegal trafficking, they are stored at various secret locations across the country. My understanding is that the Branch keeps some specimens for educational purposes of the general public and at schools and eventually destroy most of them.

Working with the staff of the Canadian Wildlife Enforcement Branch was an overwhelmingly positive experience. I felt privileged to have had such unfettered access to the specimens. If I wanted specimens from a different part of the country, they would get it for me. The dedication and professionalism of the staff was quite remarkable. I really gained an appreciation for the critical importance of what they do.

DG: Why do you feel it is important bringing to light this practice, the evidence of which remains behind closed doors?

CF: That’s the point isn’t it – to shed light on a disturbing issue by showing compelling photographs of the evidence. My intent with TRAFFICKED was to create pieces that are beautiful to get people’s attention. Then they read my narrative and realize what they are looking at. I do that on purpose. It’s my way of creating awareness.

DG: Tell me more about your decision to use the wet collodion process. Why was it significant for this project?

CF: With the emergence of digital technology and the endless proliferation of digital images, I increasingly view photography as a means to creating unique physical objects. Sometimes I create objects that are photographic plates, other times, they are hand-printed prints. It really depends on my vision for a project. The use of these antiquated photographic methods of image and photographic print/plate making compliment my science background and allow me to experiment in creating a unique aesthetic to my artwork and a deeper viewer experience.

For TRAFFICKED, I wanted to create a photographic series that transported viewers back in time when it was common to trade exotic wildlife parts, but viewed through a contemporary lens. The wet collodion process enabled me to link the past of my subject matter to the present disturbing reality. I also wanted to present the subject matter in a new way. For example, how do your portray a bear gallbladder in an aesthetically interesting way? It’s not easy. Bear parts, including paws, gallbladders and genitals command great prices on the black market. Canada is one of the world’s biggest sources of bears and so it was important for me to include a bear gallbladder in my series. Because of the nature of the wet collodion photographic process, I can spend hours creating only a few photographic plates. The exposures are long and the process prone to random imperfections. In my TRAFFICKED series, I viewed these imperfections as metaphors for the imperfections of humanity.

Last year I completed a project on abandoned parrots called CAPTIVE – also a worldwide issue. The project cried out for colour and so for this project I combined three historical methods – wet plate collodion, gum bichromate and platinum-palladium processes.

DG: You are highlighting a problem that obviously exists and needs to be remedied. Do you feel that these photographs can contribute to a dialogue in which greed, ignorance, and indifference are combatted? In what ways?

CF: A lot of people think that this is an issue that relates only to Africa and Asia but it’s a worldwide issue. Canada and the United States with their vast natural spaces are major sources of sought-after wildlife species, but the countries are also big consumers of illegal trafficked specimens.

In TRAFFICKED I thought that if I could create exquisite traditional still life images that incorporate confiscated specimens, I might get viewers to engage in a conversation about the issue and the importance of protecting endangered and threatened species.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026