Kaitlin Maxwell: Storytellers

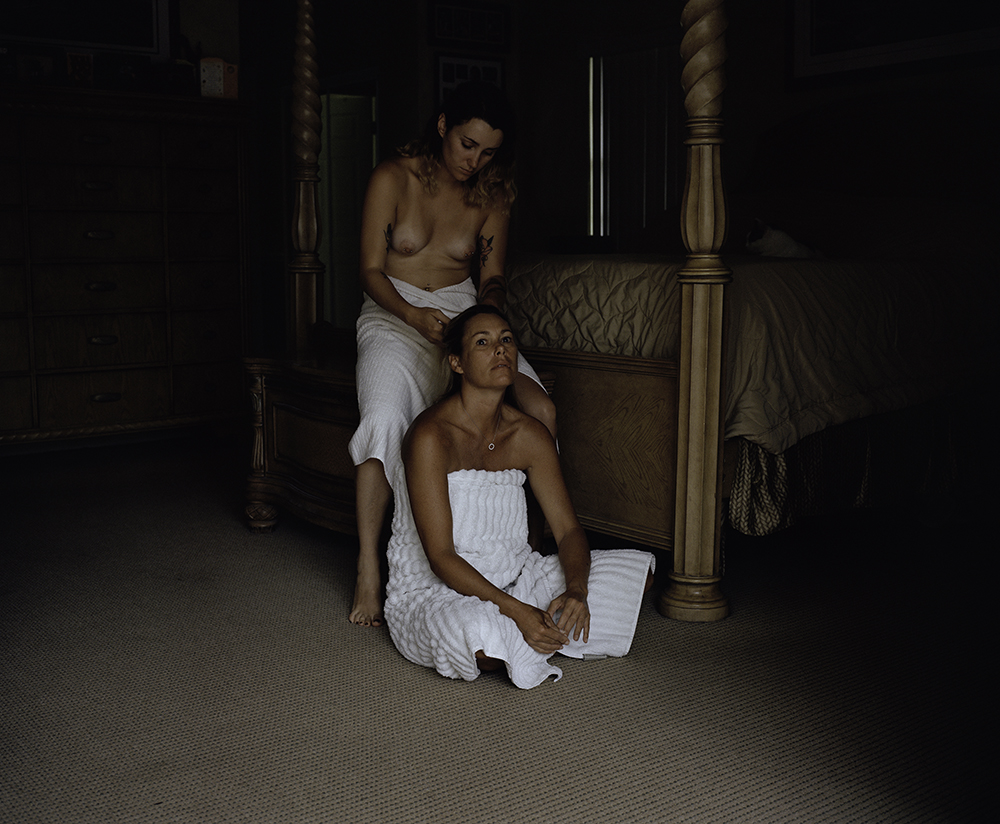

Through a series of portraits depicting her grandmother, mother, and self, New York based photographer Kaitlin Maxwell (@wutangkait) abstracts identity and transcends traditional notions of the individual. Through the use of mirrors and projections she initiates a complex conversation between surveyor and subject calling into question the gaze of the viewer and exploring the nature of objectification. Set in the low and lush keys of South Florida often at the home of her grandmother, Maxwell’s work emanates intimacy and displays themes of family, inherited memory and ultimately the collective consciousness of three women.

Kaitlin Maxwell is photographer based out of New York City. She received her BFA from the School of Visual Arts in 2016 and her MFA from Yale School of Art in 2019, where she was awarded the Richard Benson Prize.

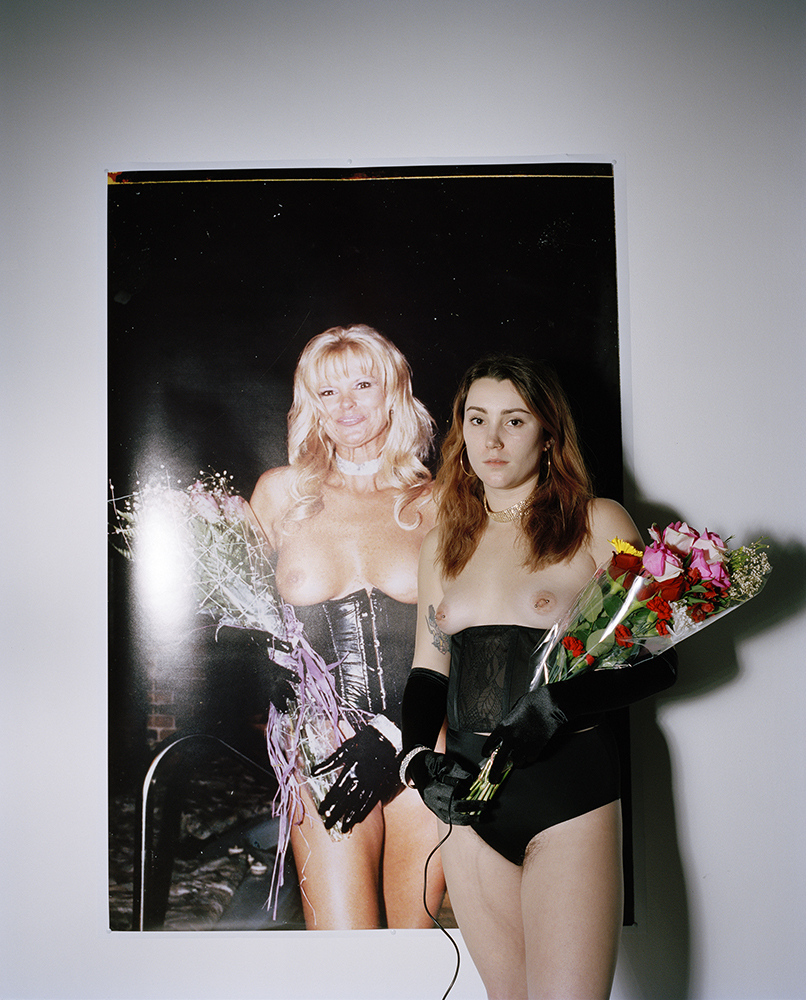

This untitled series is an exploration of family dynamics, womanhood, and the fragility of life itself. In exploring the complexities of the matriarchal relationships that exist within my family, I am challenging myself and others with the ideas of self-reflection, identity, sexuality, and objectification. My aim is to dissect human interaction and understand what our relationships with others say about our relationships to ourselves. The human condition is something that I am constantly trying to navigate and make sense of. The act of seeing and being seen are things that we are confronted with often, especially as women. By taking ownership and power of that, I am also opening up the dialogue of what it means to be in control of your own objectification. To quote John Berger from Ways of Seeing, “Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object – and most particularly a subject of vision: a sight.” – Kaitlin Maxwell

To begin I’d love to hear about the origins of this series and if there was a defined starting point. Since the work deals with yourself in addition to your mother and grandmother I’m wondering how the casual family photo evolved into a deeper exploration of womanhood and self?

It took awhile for me to gather the courage to begin this body of work. It’s something that I knew for a long time that I wanted to do, but was unsure as to how, and couldn’t manage to visualize a starting point. I think I was so afraid of not telling the story right, that I was holding myself back. I have always been interested in vernacular photography and the family archive and once I started to dissect my own, it became clear to me that I needed to explore my Grandmother’s history. As this started to unravel, a catalyst began to occur and I realized that this was about so much more than just the family archive and Grandma Candy’s past, but rather me trying to understand different types of intimacy and the dynamics that lie within the relationship you share with yourself and others, specifically within the matriarchal context.

I love the use of mirrors and projections in your imagery. After reading the John Berger quote in your statement “Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at…” the use of such props seems especially strong. Can you talk about why this incorporation felt important to you?

While this incorporation is a recurring theme within my work, it was something that came into existence subconsciously. I have always been fascinated and disoriented by the experience of seeing oneself. When you stare at yourself in the mirror for a period of time you begin to dissociate, you detach and see yourself outside of yourself. The mirrors, windows, doorways, and projections act as vessels in the work that can be used for seeing into someone or something else. Each photograph is an exchange of awareness. I am seeing the subject and they are seeing themselves. While they’re being seen within the frame, this act continues with the viewer and so on and becomes this cycle of seeing and looking. This simple gesture of observing is an important act of collaboration within my work.

Within the sequence of your images there’s an oscillation between vulnerable minimalistic portraiture and more developed staged scenes, largely in which you embody your Grandmother. How did you arrive at the decision to interweave documentary and fictitious imagery? Would you say that the inclusion of both approaches is essential to your way of storytelling?

Upon finding certain photographs of my grandmother, I got the urge to see what I would look like performing as her, but I didn’t know if I was capable of exploring that part of myself. At first, I didn’t see it as a performance, but rather me trying to replicate who she was and represented in the image. I realized that remaking the photograph wasn’t what it was about. Instead, it was an attempt to embody this aspect of femininity and confidence within my sexuality that I was intimidated by. Going to a bar and climbing on the pool table dressed in lingerie was not something I ever thought I would be able to do, but when I found this photograph of my grandmother, I could feel her confidence emanating from the picture. I needed to see if I could approach image making in a way I had never done before. This duality that is created between the images that are staged, versus the less controlled and organic moments, represent the conflicting aspects of womanhood and life. Nothing is ever simple or consistent and I want that experience to come through in my work. It’s a constant attempt at my own understanding of the human condition. The contrast between the two different approaches is an important aspect within the relationship my photographs have with each other. It’s not just about one view or portrayal of what I’m trying to say, it’s a combination of experiences and perspectives. In trying to understand more about myself, the only way I was able to deeply grasp the traits that felt most foreign to me was to see a version of myself performing as the very person I am infatuated with.

Photography can be a wonderful tool in gaining empathy and understanding for the lives of others as well as a means of exploring one’s own condition. I’m curious what you learned about your Mother, Grandmother, and yourself in the making of this work, and how the project has affected your relationships?

When I began this work one of my driving forces was to understand my mother and grandmother in a way I never had before. Even though this was my intention, I didn’t quite anticipate how much this work would change our relationship. The three of us became more vulnerable with each other. I saw my mother possess the innocence of a child and my grandmother as this powerful matriarchal figure. Seeing the vulnerabilities slowly present themselves in the two of them over time has been really powerful. The role we each play in our relationship has also been one that is constantly shifting. At times I was the maternal figure, feeling like a protector in a sense. This experience has broken down walls within our dynamic we didn’t even know existed and has allowed for more honesty to come through. As we have opened ourselves up to one another while collaborating through photography, the three of us have exposed aspects of ourselves that I know would have been inaccessible without this exchange. As much of a journey of self-exploration this has been for me, it’s also been a process of my mother and grandmother understanding my perception of them and myself.

Who was your Grandmother to you growing up? When did you become aware of her previous life?

My grandmother has always been somewhat of a role model for me, she was just a different one while I was growing up. I say that meaning I was too young at the time to understand all of the reasons why I looked up to her. Grandma Candy has always been, to me, a classic grandmother. That’s what makes her so fascinating. Parts of her history were uncovered to me at a young age, but was something that was never discussed until years later. For a while I examined her past as though she was living some sort of double life when in reality that was never the case. She’s always been the most authentic version of herself which may seem unorthodox to outsiders. She doesn’t fall into the tropes of women having “biological clocks” or reaching a certain age where they have to hide their sexual desires. She’s a 67 year old woman who likes to drink beer, would do anything for her family, and does what makes her happy. This is who she’s always been to me.

Your images contain a keen sense of time and mortality and yet seem to exist as an ever flowing chronicle. Do you imagine you’ll be engaged with this work for years to come? Can you imagine an ending?

Honestly, I don’t ever see myself not working on this series. As we continue to evolve as women and life keeps happening, there is always going to be material to learn from and create with. I think about how when I have children there will be a paradigm shift in my relationship to the work which will alter my perception of everything in a way that I’m unable to comprehend right now. In the past, I’ve thought the work had come to an end, but that was never the case. I haven’t reached a point where it feels complete or that I’ve said it quite the right way yet. I’m unsure if that will ever fully happen and I don’t believe this uncertainty is a bad thing. The struggle of figuring out how to articulate my visual language has resulted in me constantly photographing and creating pieces of this ever changing puzzle. I see this as my life’s work.

How vital is place in the traditional sense to this work? What is your relationship to Florida and would you say that the region maintains an influence over the aesthetic identity and emotional truth of this image body?

I was living in New York when I decided to start this work, so going back to Florida to shoot wasn’t something that seemed deliberate at the time, it was just where my subjects happened to be. As I began to produce more work I found myself unable to imagine it existing in any other environment. The spatial presence of Florida throughout these photographs became not only essential to the story, but also took on this role of acting as a fourth subject. The light, color pallet, and history that my family and I have in relation to this place becomes important to the work in that it carries an amount of weight that mimics the ones existing within it.

Any favorite childhood moments with Grandma Candy?

I have this very specific memory I think about often. I was in first or second grade and wanted to leave school so I went to the nurse and blamed it on a stomach ache. My parents were unable to come and get me so Grandma Candy picked me up. I’m not a very good liar and she knew that I was fine but instead of being upset, she took me to the store and bought me a Barbie Dreamhouse and let me swim in her pool all day and play with my new toys. No matter how big or insignificant the situation is she’s always let me break the rules and is right there to support me. Thinking back on it, the feeling created from this seemingly silly recollection is one that I’m constantly chasing in my work, specifically in the photographs of the two of us or me dressing up as her. There is this sense of longing for the inherent innocence you have as a child and the realization that this concept leaves you as you enter into adulthood.

In the time of Covid-19 and social distancing how has your practice changed? Do you find yourself and your work turning inward?

At the beginning of this pandemic I was putting an enormous amount of pressure on myself to use this time to make work. I have been staying in rural Indiana for the last 2-3 months in complete isolation, which has left me with nothing but time to be paralyzed by my own thoughts. I brought my entire archive with me and have been going through every single contact sheet I have, looking for clues. Allowing space to exist between yourself and your work is imperative in furthering your own understanding of what you’re doing. Through revisiting work I’ve made over the last 8 years, I am learning things about the way I see myself and other people that I was entirely unaware of. This experience has caused me to be introspective in a way I have never been before, evaluating and examining my life and my work, which seem to exist as one entity, through the lens of a constant reminder that mortality is inevitable. Trying to make sense of one’s own condition is the one thing I’ve come to realize I’ve always cared about.

Macaulay Lerman was born in the Spring in Southern California and raised in New England. As a young adult he traveled throughout the US and Canada hitchhiking, hopping freight trains, and driving his camper van. While Lerman rarely carried a camera during this time, he developed a practice of documentary storytelling through extensive journaling. To this day he remains fascinated by fringe communities and alternative ways of living, perceiving, and being in the world. While his process is largely ethnographic, in the sense that he immerses himself in the worlds he depicts, he is far more interested in emotional realities than hardlined physical truths. Above all else he values dreams and memory. A photograph exists somewhere between the two and this is why he is drawn to the medium. Lerman earned his BFA in Photography and Documentary Studies from Green Mountain College in Poultney, Vermont. Since then he has shot for a variety of organizations including the Slate Valley Museum and the Vermont Folklife Center. His work has been exhibited internationally in solo and group exhibitions, and featured in publications including It’s Nice That and Anywhere BLVD. Lerman currently resides in Burlington Vermont where he is an active member of the Wishbone Artist Collective.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Yulia Spiridonova: Wayward SonJanuary 29th, 2026

-

Ed Kashi: A Period in Time, 1977 – 2022January 25th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026