Photographers on Photographers: Saleem Ahmed in Conversation With Baljit Singh

Baljit Singh and I are Internet friends. We haven’t met in real life, nor do we really message each other all that often. I only know her through the details that she shares — the visuals she posts and the words she writes. I think we sort of just admire each other’s work from afar. I can’t even remember where I first saw her photographs. The most likely answer would be Instagram, but my memory keeps visualizing a Tumblr page.

It’s easy to get lost in the endless feeds of images all around us. It’s a little overwhelming, to be honest, and I’m guilty of adding to the overflow. But, luckily there are artists like Baljit, whose blend of family history, community storytelling, and fashion portraiture is a welcomed breath of fresh air.

Saleem Ahmed is a photographer and an assistant professor based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His creative practice incorporates elements of documentary storytelling, family history, writing, and bookmaking. Saleem developed Vista Oculta, a five-year photography workshop geared towards teaching youth on the streets of La Paz, Bolivia. He has also worked as a Media Lab Instructor for WHYY, where he taught media literacy to high school and middle school students in the Philadelphia School District.

Saleem Ahmed is a photographer and an assistant professor based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His creative practice incorporates elements of documentary storytelling, family history, writing, and bookmaking. Saleem developed Vista Oculta, a five-year photography workshop geared towards teaching youth on the streets of La Paz, Bolivia. He has also worked as a Media Lab Instructor for WHYY, where he taught media literacy to high school and middle school students in the Philadelphia School District.

Baljit Singh is a photographer based in Mississauga, Canada. Her style ranges from travel/documentary to creative portraits and editorials. Baljit’s work in the analog medium aims to document brown bodies in a new light while exploring themes of nostalgia, immigration, and social issues in the South Asian community. Baljit has been a part of international group exhibitions in the Greater Toronto Area, London, and California. With recent publications in British Vogue.

Saleem: First off, I just want to thank you so much for taking the time to answer some of my questions. Let’s jump right in! I know we both have some similarities in our beginnings in photography. When did you realize you wanted to pursue photography?

Baljit: I was always into the visual arts growing up. In school I always took some form of art or design class to kind of fuel my creativity. And then around middle school I picked up our family point-and-shoot camera and started taking pictures of random objects and landscapes. Facebook had just become a thing, so I started posting online and sharing with my friends.

They were so supportive and they validated these photos of mine. And mind you, looking back, these were like really shitty pictures of flowers, a garden hose, and a super-contrasty sky. But it made sense back then? Like, it was still ‘cool,’ haha. After that, I started doing my own digging and learnt more basic techniques to elevate my ‘craft’ as a middle schooler. I took some photography classes in high school that really made me more passionate about the medium. Learning about other photographers and how they made careers out of taking portraits was interesting to learn about. Especially since none of them were POC because I felt it was easier to pursue these things if you were white.

And so then while entering post secondary, as much as I wanted to pursue photography in some sort of art school, I guess I was still confused about it and never really stood up for myself or pushed myself to go further institutionally with photography. It also didn’t help that at the time my parents only thought of it as a hobby.

In college I was involved in a lot of community work outside of school, especially surrounding the Punjabi Sikh community. Being involved with people; reflecting on our history; learning about the current state both in the homeland and out here in the west. Seeing how we all have the power to make a global impact made me realize how big the world was. And how photography isn’t just about taking some pretty pictures and posting it on the Internet. But it can be a lot bigger than that. I have the power to share stories and make people feel connected and allow them to think beyond themselves.

I guess that was the point in my life when I started asking myself, ‘what’s the intention behind this picture?’ From then, on once I graduated, I started pursuing photography full-time.

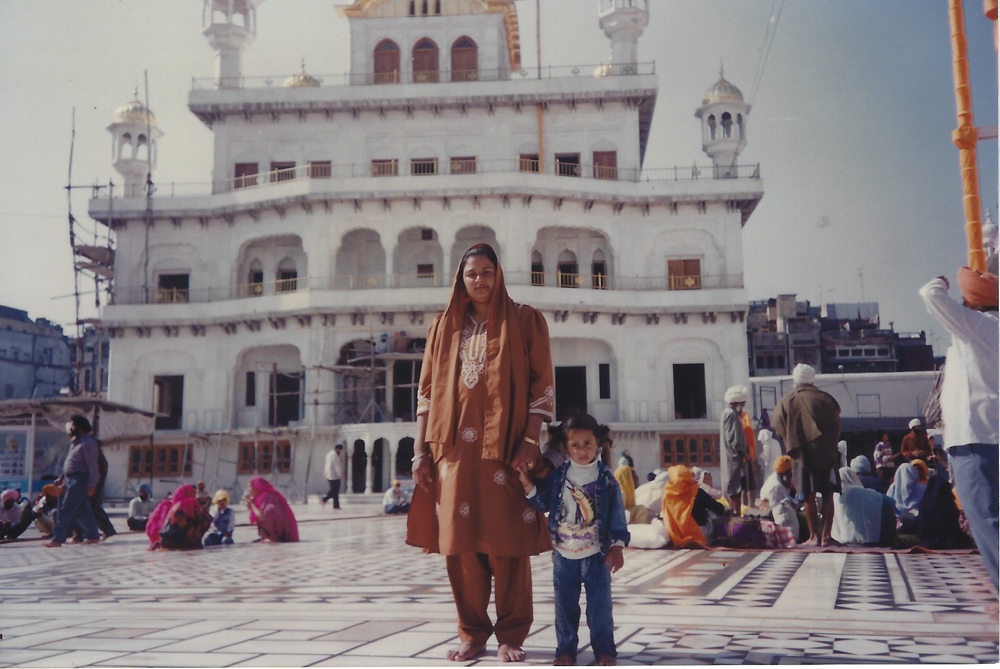

© Baljit Singh, Family Archives, 1996

S: Wow, you basically answered half of my follow-up questions in that response… Was there any friction in your family when you decided to pursue art-making?

B: I hate always using this cliché about living in a brown family and them expecting you to become a doctor, engineer, or a lawyer. But, to a certain extent it’s true. Even if they never directly say it, parents do want us to always pursue a more stable career. Something they understand. A 9-to-5. A consistent income. They’ve never had to think beyond that. Because for them it was about survival.

So it makes sense why — when your child tells you about wanting to do photography full-time — they almost start glitching because they don’t understand.

How am I going to make a hobby my career? Will I be able to financially support myself? What are these ‘dreams’ that I speak of when my parents never were able to pursue theirs? Who could I reference to them, that looked like me, who’d done it in the past?

And quite honestly I didn’t even have these answers to defend myself.

There was no fairy-godmother-art-historian mentor who could explain how ‘normal’ pursuing a career in the arts was. All I knew was that this was something that I was decent at, it made me happy, and was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.

S: I can definitely relate to a lot of what you’re saying, haha. I remember things being quite intimidating in the beginning (and still are!)…

B: There were many hard days, but also good ones. When I would get certain accolades relating to photography my family would beam with pride and joy. They would brag about it to their friends and relatives.

When they saw me struggle financially, they helped out. But they would still advise me to get another job or maybe pursue something more stable for the time being. It was all coming from a place of good intent, but they didn’t realize the negative impact that these statements have. Because you’re already second guessing yourself anyway.

So I started speaking to them in their language — using references from people in our history who took the road less travelled. Not that I was trying to compare myself to them, but rather explaining to them that our world is what we make it. There is more than one way to live a happy, fulfilled life. I am grateful to the fact that despite the friction, they were still open to learning and supporting however they could.

S: Family and community clearly play a meaningful role in your life. Can you speak about your family and community’s influence on your art?

B: Growing up, I want to say, I had a very ‘normal’ childhood for the most part. It was a very bountiful environment — living with my parents, two younger siblings, and both sets of my grandparents all in one house (with the odd uncle or cousin also living with us at certain points of my life). And I want to acknowledge that that’s not everyone’s experience, so I am grateful for my privilege in that sense.

Going into photography I never intended to fall into a certain genre. I guess I naturally fell into more documentary community-based art. Shooting and sharing stories of my community makes me feel whole — I know, the corniness jumped right out — and it has fueled my passion for photography. It’s the one thing that helps me stay grounded.

S: I love going through family albums and I’ve seen you share older family photographs too. How do these images relate to your work?

B: I absolutely love pulling references and inspiration from old archives. The aesthetics of it are so pleasing. I’m always drawn to people’s old family albums and looking at how they dressed and how they posed. In that particular time period. In that part of the world. All of it. It’s so fascinating to me. Even when it comes to my personal family albums, maybe a part of me wants to continue this analog tradition so I try to incorporate an element of that nostalgia in my work as well.

S: Do you work exclusively in analog photography? What draws you to that medium?

B: I would say around 80-90% of my work is analog. I try to use it as often as I can, but I understand it’s just not possible during some environments or shoot setups. I guess a part of it is the nostalgia factor that I’m obsessed with; trying to keep the analog method alive. But mostly because it allows me to take my time and put more intention behind the photo.

I used to sift through thousands of pictures to select from. Now it’s a lot less, and my future-editing-self thanks me, haha. It allows me to perfect my craft and work with light more because I can’t see the image right away. I need to get all the settings and composition right. It took a lot of practice, but now taking analog pictures it’s as easy as breathing for me.

I love the anticipation of getting the developed film back and seeing the final results. Apart from the aesthetics of the film pictures, it just feels a lot more satisfying as a photographer to hold your analog images and say you really made this.

S: You recently traveled to Punjab. Can you tell me about that experience?

B: I’m not even going to lie, this is also going to sound very corny but it was a very ‘Eat, Pray, Love’ trip for me. I had been in this constant work-mode for a few years back-to-back, and even though it was still in the creative field, it wasn’t the work I needed for my soul.

So, I took two months off to reset and try to centre back to what I really wanted to do in the first place. Being with family, and surrounding myself with the history of Punjab, and being around people and places that made my parents who they are was really special.

S: Were you working on a specific project while in Punjab?

B: I had a bunch of half ideas going to Punjab. If they worked out, great. If they didn’t, I promised I wouldn’t be too hard on myself. Logistically, it’s hard to control certain factors in other places, so I let myself be flexible to what was to come during the trip.

I documented my family, some historic sites, and experimented with a couple of photo series with friends and family. But being there did provide me with clarity and the inspiration I needed for my next trip to Punjab, so I know the level of preparedness to come with.

S: Did you learn anything unexpected from your time there?

B: I learned that our village in Punjab, before the partition in 1947, was home to a Muslim community. And when my great grandfather’s family moved over from the Pakistan side of Punjab with the other families, they kept the Masjid in the village as-is, and continued their own Sikh practices inside. It was cool seeing that architectural piece of history still exist to this day, especially since Punjab really isn’t known for their preservation of historical buildings/landmarks.

S: Is there anything you’ve seen, read, or heard lately that inspires you?

B: I’ve recently started reading more about “The Seven Queens of Sindh.” Exploring more into the folklore I’ve read as a child. Like stories of Heer Ranjha and Sohni Mahiwal. And then listening to all these love ballads by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan inspired me to think about the sheer god-like devotion these couples had for each other. So right now I’m just exploring those themes in a future project I’m working on which I’m excited to share.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026