Photographers on Photographers: Derrick Woods-Morrow and Concerned Black Image Makers

Over the last month I’ve spent time on multiple devices, using multiple strategies to catch up with the now scattered members of Concerned Black Image makers (CBIM). And as a national pandemic overwhelms the USA this interview connects the dots of Black voices who are creating new images for seeing ourselves doing blackity-black things, despite the pressure we feel from a world that consistently values our cultural production, but not us; the makers, who are engineering American culture.

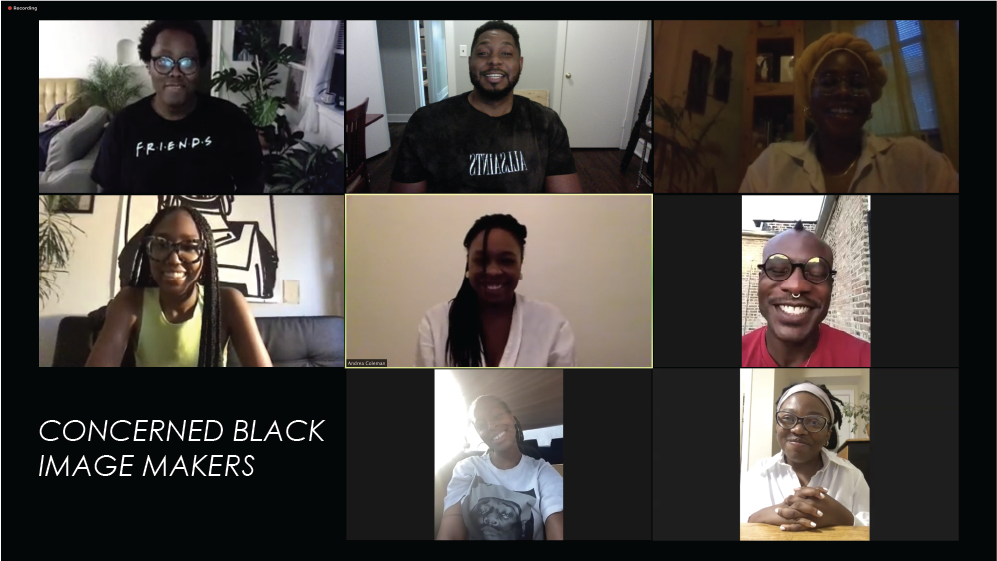

Still…the members of Concerned Black Image Makers (CBIM), a Chicago based photography collective of founders Zakkiya Najeebah and G’Jordan Williams, and members Maya Iman, Sierrah Floyd, Jamillah Hinson, Andrea Coleman, Darryl DeAngelo Terrell and myself – Derrick Woods-Morrow, have gathered throughout quarantine, if for nothing more than to laugh on Zoom calls, encourage and be real with one another via WhatsApp – occasionally spreading love by leaving each other voicemails.

In the past, a number of CBIM members have participated collaboratively in my performances, photographs, and compositions — in my work with Black Fol(x) our bodies touch each other, skin folding over, creasing, hanging and constricting around gendered garments, and around other bodies, around the expectations of what various Black people should be doing with their time together, so much of which is now a digital meditation due to Covid-19. (I haven’t made any of this work in the year 2020 for fear of putting the very people the work intends to protect and highlight at greater risk of something they are already at the greatest risk for).

Now, more than ever, I feel that ‘touch’ has become an abbreviation of the physical. A realm away from where skin meets skin. To touch base is to be on the go; is to press down keys and buttons from the safety of one’s home. To “click” and unsurprisingly to “meet” exists mostly through digital platforms such as Google, Facebook Live, Zoom calls (or the gloryhole hanging in my living room).

to keep us going,

to stay afloat in kinship,

our family abundantly chosen.

we have confided in each other,

our highs and lows,

our lack of interests in the outside world.

None of us are really present, we are all sort of AWAY.

The members of CBIM are part of a generation of makers raised on the internet. We are no strangers to the disconnection.

If we are not returning to the past, and are choosing to build a new future,

How can a group of Concerned, Black, Image Makers help us get there?

CBIM Mission Statement

As artists/culture workers we share and explore the methods we have utilized to create meaningful work, offering suggestions as to how we can continue to build a visual continuum that conserves Black identities. We facilitate dialogues and collaborative projects amongst Black lens-based artists whose concerns are specific to Black communities, while also offering critiques, support, and alternative visions of a “Black” aesthetic. In exploring these methods, we seek to conserve the visual identities of work produced by both emerging and accomplished photographers. We ALWAYS prioritize critical connections and inquiry between photographic practices, as well as the need for diverse representations of Black communities and photographic stories visualized through a Black lens.

G’Jordan Williams is a photographer, library scientist, and lover of all things beautiful. Seeing art as language, they’re compelled to use mediums to communicate with themselves and others, especially when creating work that is communicative with the Black Diaspora. Specifically, G’Jordan holds impassioned interest in the intent, conceptualization, and dissemination of the Black image in art; constantly questioning the path and standards of Black images popularized today.

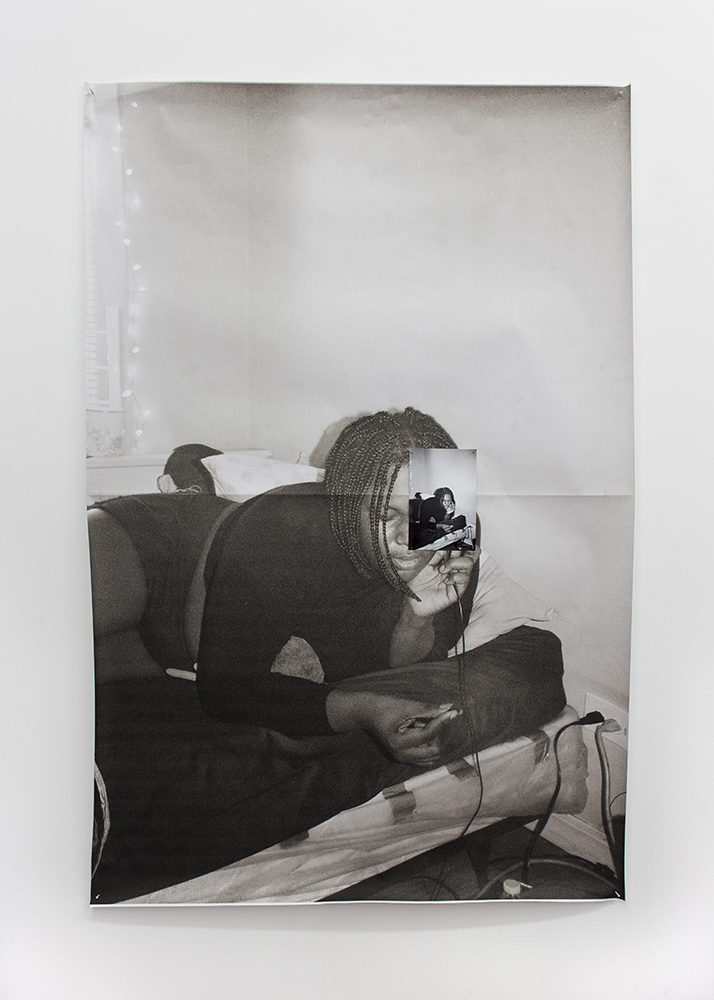

shadow work (II), the life long, sometimes arduous, process of illuminating that which is forgotten or neglected within us. When reaching within, we have to face whatever’s festered and become an entity of its own © G’Jordan Williams

Derrick Woods-Morrow: What do you believe the benefit of CBIM is to the photo world?

G’Jordan Williams: CBIM is intended to be a space where, regardless of how much institutional visibility, pull, or clout whatever fuck you want to call it…regardless of what someone has, that’s not a factor when it comes to us all convening.

So you may see someone who just started off like taking pictures a year ago at one of our dinners sitting next to Dawoud Bey and they’re both going to be treated as the same person. You know, aside from Dawoud being appreciated as someone with experience, right? But otherwise it’s like, you’re a photographer, just like Dawoud, would you like to fuck with us tonight? Cool, come sit down.

G’Jordan Williams (cont’d): As far as how the practice functions within the CBIM – it’s about giving us a space to be as diverse as we are. Which is something that speaks largely to Black art in general. There are a lot of Black artists that feel the pressure to carry blackness on their back. There are a lot of Black queer artists that feel the pressure to carry queerness on their back. As we diversify and are able to create and appropriate our own platforms, we should be able to create spaces where Black people can just feel free to create anything, and to make mistakes. Because we just don’t have enough space for that. Now, anything that’s Black has to be like super dope, and thought provoking and awesome. It can’t just be something that’s silly. You know?

“synagogue hate crime suspect an educated, suburban accountant” © G’Jordan Williams

Zakkiyyah Najeebah

Zakkiyyah Najeebah is Chicago based visual artist, educator, and independent curator. Her work is most often initiated by personal and social histories related to family legacy, queerness, community making, intimacy, and Audre Lorde’s naming of “the erotic” . Her practice borrows from visual traditions such as social portraiture, video assemblage, and vernacular found family sourced materials. Currently, her body of work prioritizes social relationships related to queerness, Black women’s identity formation, family, social architectures and the desire for connectedness. Zakkiyyah is also a Co-founder of CBIM (Concerned Black Image Makers): a collective driven project that prioritizes shared experiences and concerns by lens based artists of the Black diaspora.

DWM: Where would you like to see CBIM in the near future?

Zakkiyyah Najeebah:

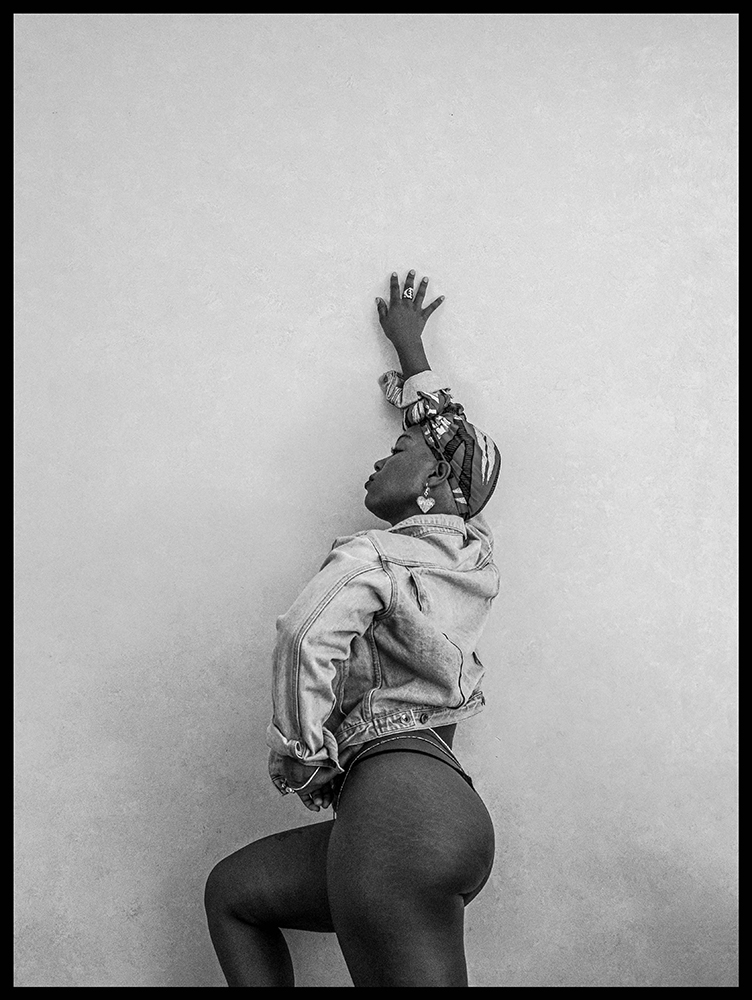

Untitled © Zakkiyyah Najeebah

DWM: And where do you see CBIM in the distant future?

ZN: I think it would be amazing if Concerned Black Image Makers could grow into an annual symposium in which Black photographers and Black lens based artists and Black filmmakers from all over could convene. I think that would be really amazing. If that could happen primarily in Chicago and be an annual gathering where people are facilitating workshops, facilitating panels and dialogues, as well as screenings. It would also be amazing if there could be an exhibition component to that as well.

I really do think that what Concerned Black Image Makers is doing extends well beyond Chicago. And I would hope that in the future, that we have built relationships with other photographers throughout the Diaspora who are not here in Chicago, who may not even be here in the States, and it would be amazing to have those dialogues. Right now there’s a time for that to open up a little bit more. With COVID, a lot more people are open to virtual programming. But even beyond COVID, this is going to be a continuation – I definitely think there’s going to be an increase in more virtual programming because people see the benefit of its usefulness in building relationships with people who may not be in your city or people who aren’t local, but might have similar ideologies or similar methods or practices to the work that they’re making. So that’s where I see CBIM in the future. One of the other things that we had discussed is to have a publication of some kind featuring the work of Black photographers, Black lens-based artists, with a collection of interviews. So that has been on the table, thinking of some sort of independently published book that could be made with the collection of those interviews. It could also include essays on photographers that are featured in the book.

Installation shot I, A Different Kind of Love Story: For Us an investigation of Black women’s identity at ADDS DONNA Gallery Chicago in 2019. © Zakkiyyah Najeebah

DWM: Zakkiyyah, where can CBIM take us, and are we all ready for that?

ZN:

Installation shot II, A Different Kind of Love Story: For Us an investigation of Black women’s identity at ADDS DONNA Gallery Chicago in 2019 © by Zakkiyyah Najeebah

Maya Iman

Maya Iman is an artist specializing in photography, film, and art direction. She was born and raised on the South Side of Chicago, now based in Los Angeles. Storytelling is manifested in her work through capturing authentic emotions and experiences. Her work explores the human experience and social inclusion in the communities of people of color. The preservation of stories, beliefs, and emotions that she showcases as an invitation for her viewers to engage. In 2017 Maya produced her first solo exhibition “Flawed” featured at AMFM Gallery in Chicago. After the exhibition, she was nominated for the Black Excellence Award in 2018 by the African American Arts Alliance Chicago as well as for ICP’s “Talk in Images: Body”. Her work has been featured in exhibitions at the University of Chicago “Between Vision + Principle” and Mana Contemporary “The Hands of a Nation”.

Trina & Matt Muse Diptych © Maya Iman

DWM: I want to celebrate your recent success, Maya. Your project “Don’t Forget About Us,” is an ongoing effort aimed at exploring human experience and social inclusion in communities of people of color, and just received an award from Getty Images.

Maya, could you please talk about the award you just received, and what that means to you as an artist making work during the pandemic? You also recently lived in Chicago, where CBIM was founded, and actually moved away during the pandemic. Can you speak to how it is to be a part of the CBIM community from LA? What are you working on now? And how is it informed by any of the dialogue happening in CBIM at the moment?

Maya Iman: I’m very grateful and honored for this creative bursary! Winning this grant will provide the space and financial security for me to continue my art practice during this pandemic.

Moving to California and living here as a transplant during this time has been an eye-opening experience. I’m grateful to have this time alone to reflect on my goals during this transitional period of my life. But it’s definitely been hard for me to be away from family and close friends that I have known for many years. Being in California, I’ve been able to connect with a lot of artists that I’ve admired. People like Jaylien, Kene O, Kendall Miles, Wesley Dogan, Black Lives Matter LA. It’s been surreal to have the opportunity to collaborate and build with so many talented people.

I’m looking forward to creating new work and connecting with the art community here. Being away from CBIM has been difficult. I miss the community, friendships and safe spaces. At the same time, I’m excited to connect with more artists in LA to grow the collective here. I am currently working on a music videos for different clients to stay afloat. I’m looking forward to being on production sets to get more film work in my portfolio at the moment.

Trina & Matt Muse Diptych © Maya Iman

Darryl Terrell

Darryl DeAngelo Terrell (b. 1991 Detroit, Mi) is a BLK queer artist, digital curator, and writer, currently based in Detroit, Mi. A recent MFA graduate from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago where he studied Photography, under the supervision of Roberto Sifuentes, Ayanah Moore, and Xaviera Simmons. Darryl’s work is centered around the philosophy of F.U.B.U. (The Shit Is For Us) He thinks about how his work can aid to a larger conversation about blackness, and it many intersectionalities. Their work explores the displacement of black and brown people, femme identity, and strength, the black family structure, sexuality, gender, safe spaces, and personal stories, all while keeping in mind the accessibility of art. Darryl is a 2019 Kresge Arts In Detroit Visual Arts Fellow, 2018 Luminarts Fellow in Visual Arts, a 2017/18 Hatch Project Artist in Resident at Chicago Artist Coalition, 2017 Artist in Resident at ACRE, a semifinalist for the 2017 Edes Fellowship. Darryl has also shown at The Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts, Brooklyn, NYC YC, the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, Il, Xpace Cultural Centre, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, the Hunter Museum of American Art in Chattanooga, TN, Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art in Scottsdale, AZ and The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington DC.

#Project20’s Group shot, Cyanotype, Black Tea, Black Coffee, Chicago, 2017. If you kick us out of our hood, I put us on your white walls. © Darryl Terrell

#Project20’s Group shot, Cyanotype, Black Tea, Black Coffee, Chicago, 2017. If you kick us out of our hood, I put us on your white walls. © Darryl Terrell

Documentation of Dion Being A Bad Bitch…Periodt © Darryl Terrell

With Expensive Taste…That’s It, Ain’t Shit Broke Round Here © Darryl Terrell

Andrea Coleman

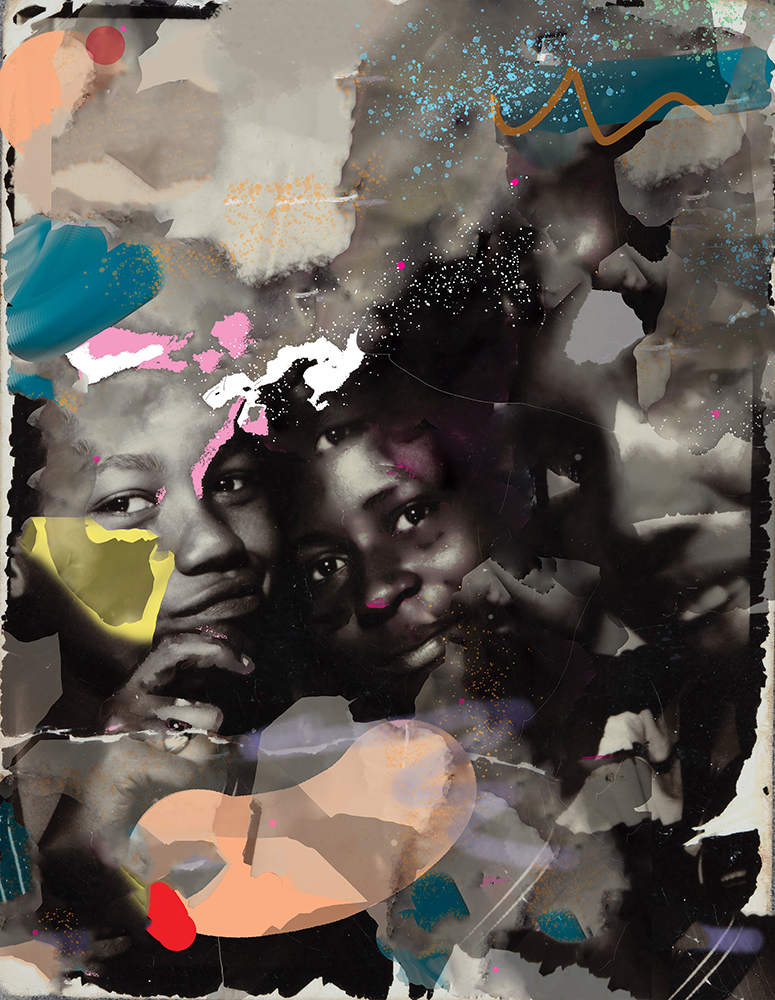

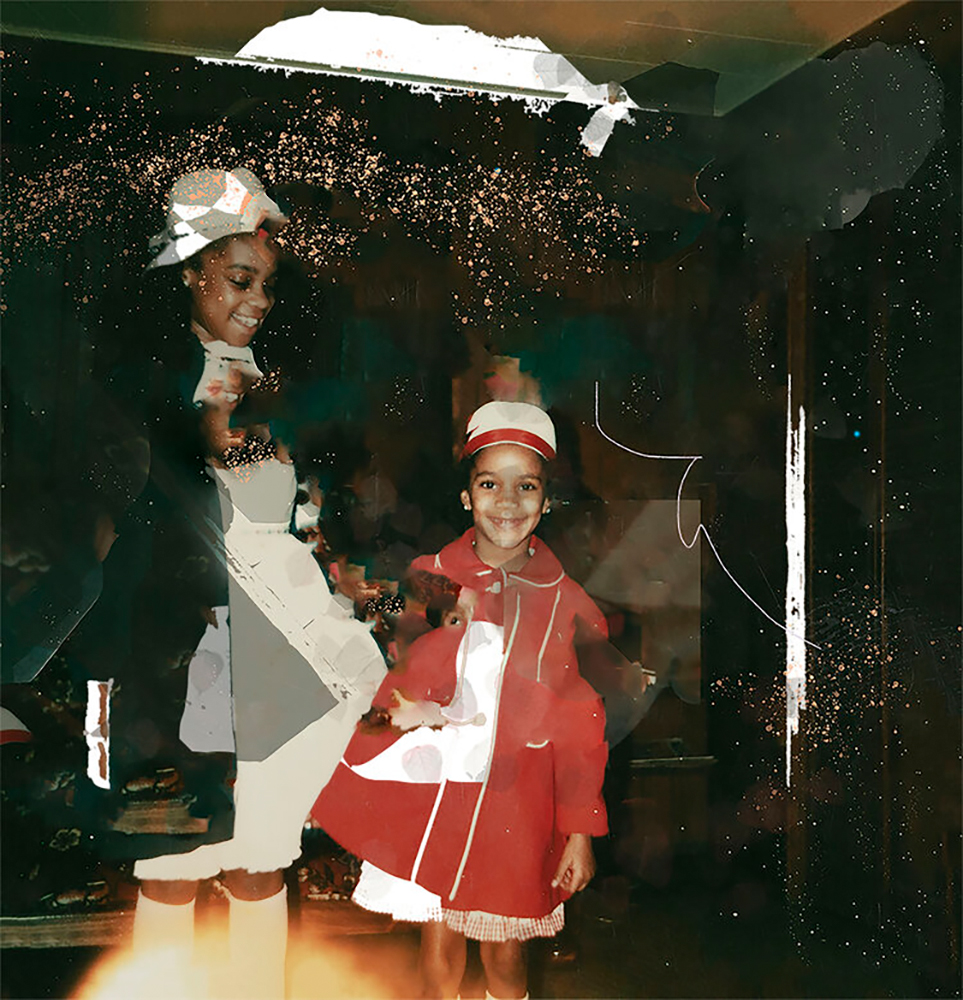

Andrea Coleman’s work derives inspiration from using representational photographic family memorabilia, clippings and videos as a basis to produce a series of digital paintings. Combined with expressive mark-making and coloration, each piece addresses elements of nostalgia and a distorted form of memory. Along with compiling material from VHS tapes, she digitally manipulates images found in photo albums to challenge ideas of authenticity and re- appropriate the aesthetic of aura and memory. Based upon my own familial relationships and passed down information, the work investigates the intuitive interconnectedness and multidimensional relationship between snapshot and portraiture.

DWM: Can you talk about your work, and how it fits into the community of CBIM?

Jamillah Hinson

Jamillah Hinson is a Chicago based independent curator and arts programmer focused on exploring the works and concepts derived from the rich diversity found throughout the African diaspora. Hinson’s work often delves into the everyday life of Black people across various cultures and ethnicities, examining and glamorizing often erased components of Blackness in the Americas and the Caribbean. Currently, Hinson’s practice has evolved to encompass the mythical and spiritual practices of Blackness, which are often intertwined with the everyday.

DWM: We are extremely fortunate to have two independent curators in the collective. Jamillah Hinson, and Sierrah Floyd. Jamillah, I’d like to know how CBIM has influenced you as an independent curator?

Jamillah Hinson: As a curator who works primarily in the Black American & Afro Caribbean communities, and in turn is forever enchanted by the richness of the cultures found within, the spaces Concerned Black Image Makers has created where the presentation, context and circulation of Black film, photography and image-based work, is consistently questioned, has been integral for my continuous growth. The ability to have these direct conversations with artists and cultural workers, or watching these conversations unfold, has allowed me to constantly question my own curatorial practice and how I can project and center the gaze of Black experiences. I believe my own examination of my practice, as well as the works I consume, has become more refined and as a whole due to being part of CBIM.

Beyond the restraints of classically trained versus vernacular artistry, Black imagery will forever be a radical act, even in the most passive sense, that demands nuanced examination and celebration.

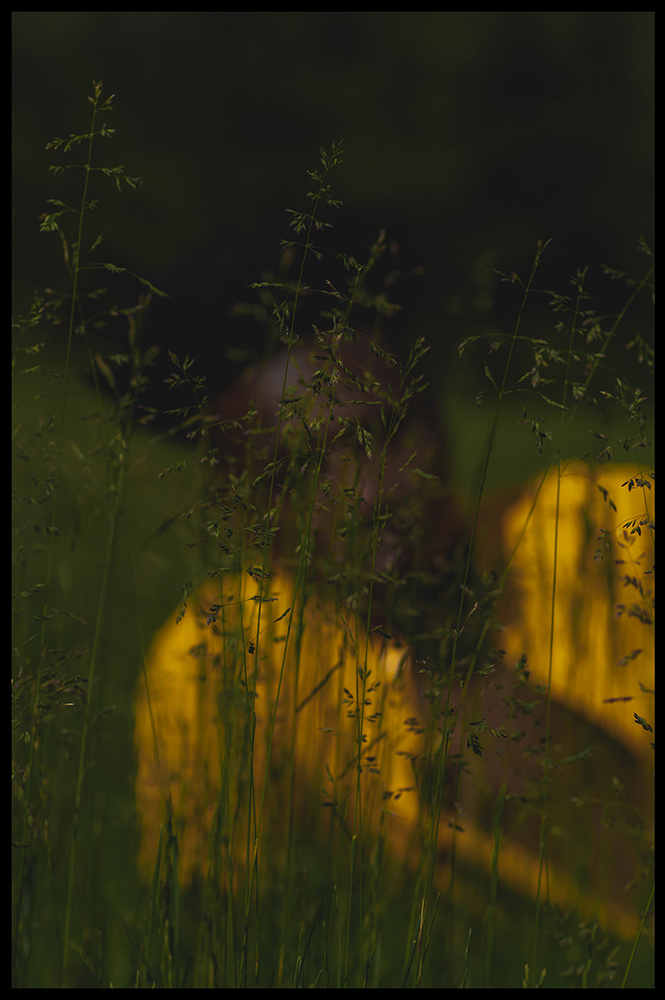

time now for ghosts was the exploration of traditional nature centered spiritualities, and realities, as they are interpreted through the practices of Black artists working with an afro-futurist lens and hand. This is an exploration of the future, as we return to our pasts. time now for ghosts looks into the intersections of time and relativity, to expand our understanding of when – what does it look like for our ghosts to come from the future? This question is asked within the presence of the Black body and the Black consciousness within the natural world, whether that world is terrestrial or beyond the cosmos. This show was a world of Black experiences concentrated into a living archive of sorts. These practices, and the works that culminate from them, become an exploratory reference of the black body and the black consciousness within nature and beyond time.

time now for ghosts was a show that was close to my heart for many reasons, one of which was the display of image making from Black women and femmes, particularly the intimacy and cultural commentary that was interwoven into the work.

There were two films shown simultaneously, Franchesca Lamarre’s A Good Cry (Yon rel Bon) (2018) and Kearra Amaya Gopee’s How to Break a Horizon (2019). Both films were steeped in identity, black american/haitian and trinidadian, blackness within nature, surrealism. And black spiritualities and practices throughout the diaspora. While LaMarre’s piece was displayed on a screen, Gopee’s work was allowed to engulf its own wall, blowing the proportions and allowing the viewer to step into, or be dragged into, the film. In juxtaposition, Lamarre’s gave a sense of peeking into this recorded moment, only to never fully grasp it. A physical representation of being allowed into a world, or culture, or standing outside it while being allowed the presence of its energy.

Alongside the digital films, the du Monde Series (2018), cyanotypes created in collaboration between Krista Franklin, Alexandria Eregbu, and Devin Cain, sat between two windows in the near Gopee’s film. As time now for ghosts was partially meant to explore varying interpretations of sensory intake, it felt necessary to explore varying techniques of image making, particularly digital images presented next to photograms. As this show was heavily drenched in concepts of blackness in nature through the work, having works created through nature from the hands of black folks set well within the space.

time now for ghosts, in its completion, was aiming to fully represent various methods of storytelling, with that came the story of Black folks across the diaspora being told through mouth, light, or lens.

Sierrah Floyd

Sierrah Floyd (b. 1997) is an art historian, researcher, and independent curator, who is currently focusing on the intersection between financial literacy and art entrepreneurship. Through coordinating intentional networking events, and professional development workshops she supports art professionals in practically sustaining their practice. Floyd is founder of I’m From Here, which is dedicated to connecting early art professionals with established art professionals and advising them on how to approach financial obstacles. Also, Floyd has coordinated a series of intentional networking and co-coordinated the 2 nd Annual Bachelor of Art History Symposium showcasing theses from emerging art historians. Her curatorial research focuses on providing solutions for how to implement wholistic and socially effective perspectives of contemporary Black artists and communities into the core curriculum of institutions that directly affect Black history, historical objects and art. Floyd received her Bachelor of Art in Art History from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2019, with a concentration in African and Asian contemporary performance, photography, and painting.

Sierra Floyd, On Her Curatorial Research and Connections to Asian Art & Culture:

“Perceptions of Modern and Contemporary Chinese Art” panel Moderated by Harry C. H. Choi at the 2nd Annual Bachelor of Art in Art History Symposium (April 24th, 2019) Speakers from left to right: Sierrah Floyd, Alejandra Vargas, Yihang Liu

Derrick Woods-Morrow

Derrick Woods-Morrow (b.1990 Greensboro, NC) envisions ‘place- making’, ‘playfulness’ & ‘experimentation’ as necessary forms of activism for trans, gender non conforming & queer bodies of color. He received his MFA in Photography from the School of Art Institute of Chicago in 2016, and was most recently an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Photography and teaching artist at the University of Illinois Chicago. His work exhibited in collaboration with Paul Mpagi Sepuya in the 2019 Whitney Biennial; in the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago; in YNCI V: Detroit Art Week Expo; in Photography Now: THE SEARCHERS, curated by Maurice Berger and Marvin Heiferman at The Center for Photography at Woodstock; and Down Time: On the Art of Retreat at the Smart Museum Chicago. In Winter of 2019, his second short film, ‘much handled things are always soft’ debuted in collaboration with the VISUAL AIDS 30th Annual Day With(out) ART programming at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Museum of Contemporary Art LA, The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, The Brooklyn Museum, The New Museum & over a hundred institutions worldwide. He is the 2021 Edith and Philip Leonian fellow at the Center of Photography Woodstock, 2021 Bemis Residency Recipient, and an alum of the Fire Island Artist Residency, Chicago Artists Coalition’s Bolt Residency, and is a recipient of the 2018 Artadia Award – Chicago.

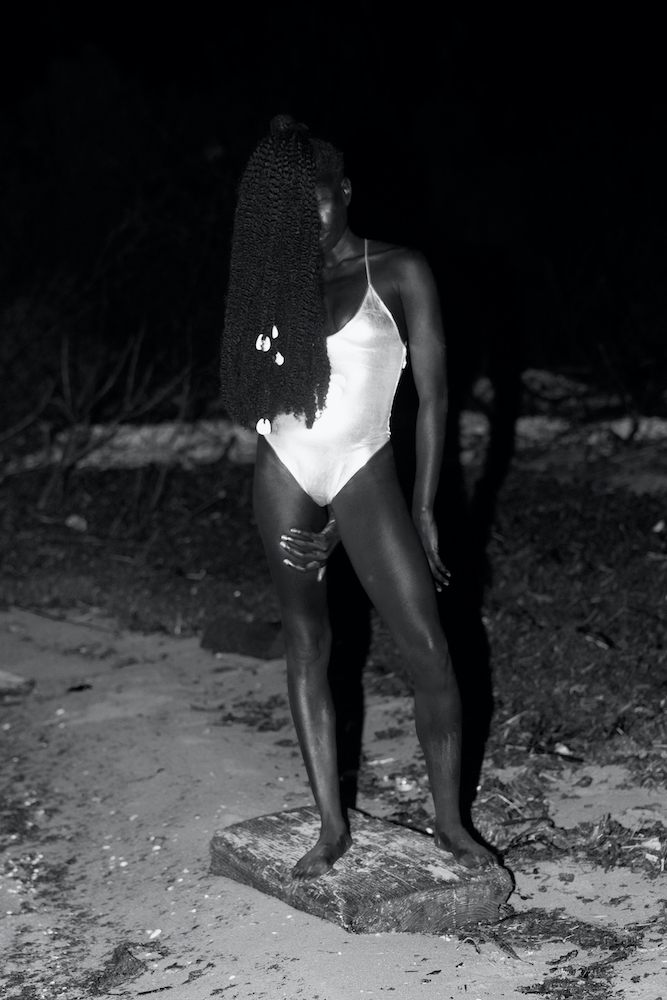

Excerpts from Acts of Boyhood Divination: Negation of Sight (Photographic Documentation of 2-hour durational performance on Lincoln Beach) 2019, © Derrick Woods-Morrow

Kendra at Nightfall | Facing Seabrook © Derrick Woods-Morrow

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Hillerbrand+Magsamen: nothing is precious, everything is gameOctober 12th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Q&A WITH PHOTO EDITOR JESSIE WENDER, THE NEW YORK TIMESAugust 22nd, 2025

-

Christa Blackwood: My History of MenJuly 6th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Researching Long-Term Projects with Sandy Sugawara and Catiana García-KilroyMarch 27th, 2025

-

Dodeca Meters: Arielle Rebek, Kareem Michael Worrell, and Lindsay BuchmanFebruary 7th, 2025