Julia Rendleman: Sisterhood of Recovery

©Julia Rendleman, Women of the Heroin Addiction Recovery Program at the Chesterfield County Jail outside of Richmond, Va. “pray out” a participant as she is released from jail.

In her remarkable photographic essay, Sisterhood of Recovery, Julia Rendleman introduces us to two sisters in a jail in central Virginia—both participants in a peer heroin addiction recovery program—and their mother on the outside, raising one of the sisters’ four children. Photographed over multiple occasions from 2017 to 2020, we get a glimpse of the toll of the opioid crisis, and how incarceration affects entire families and communities, not just the person behind bars.

Julia Rendleman is a freelance photojournalist based in Richmond, Virginia reporting on human health, poverty, resilience and the environment. Her work has been used to advocate for affordable housing reform and for harm reduction approaches to substance abuse and rehabilitation.

Her work has been supported by grant funding from the DocumentaryProjectFund, the Howard G. Buffett Fund for Women Journalists and the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Julia received hostile environment training through Reuters (2019).

A photo Julia made of two young ballerinas at the foot of the Robert E. Lee monument during the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 went viral. Julia now serves on the board of @brownballerinas4change, an organization created by the ballerinas and their mothers.

Julia works for The Washington Post, The New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, U.S. News & World Report, National Public Radio and other national news outlets. She is a member of @womenphotograph and is available for assignment in Virginia and beyond.

©Julia Rendleman, Jeremy talks with his mother Tera Crowder while James plays with Jaydon in his grandmother Deborah Crowder’s arms during a video visit with their mother, Tera, at the Chesterfield County Jail. Tera’s four children are: 16-year-old twins Jeremy and Jacob, seven-year-old James and three-month-old Jaydian. “You’re lucky with the twins. Jacob takes it a little harder … they don’t say nothing bad about you. They just don’t expect much,” Deborah said to her daughter during the visit.

Sisterhood of Recovery

“We’ve been running jails now for 200 years. What we’ve been doing is not effective. Anyone who tells you it is, is lying to themselves. We have the same people coming in and out, in and out. I just reached the point of absolute frustration with the system,” Chesterfield County Sheriff Karl Leonard said.

Sheriff Leonard started the in-jail, peer-to-peer Heroin Addiction Recovery Program (HARP) at the Chesterfield County Jail in central Virginia after he saw the need to treat heroin addiction within the criminal justice system. Stephanie and Tera Crowder are sisters who worked their way through HARP. Their mother, Deborah raised Tera’s four boys while she was incarcerated.

I followed their story for two years, in jail and then, outside of it.

©Julia Rendleman, Women participate in a Narcotics Anonymous-style meeting in the Heroin Addiction Recovery Program, or HARP, at the Chesterfield County Jail near Richmond, Virginia on October 23, 2017.

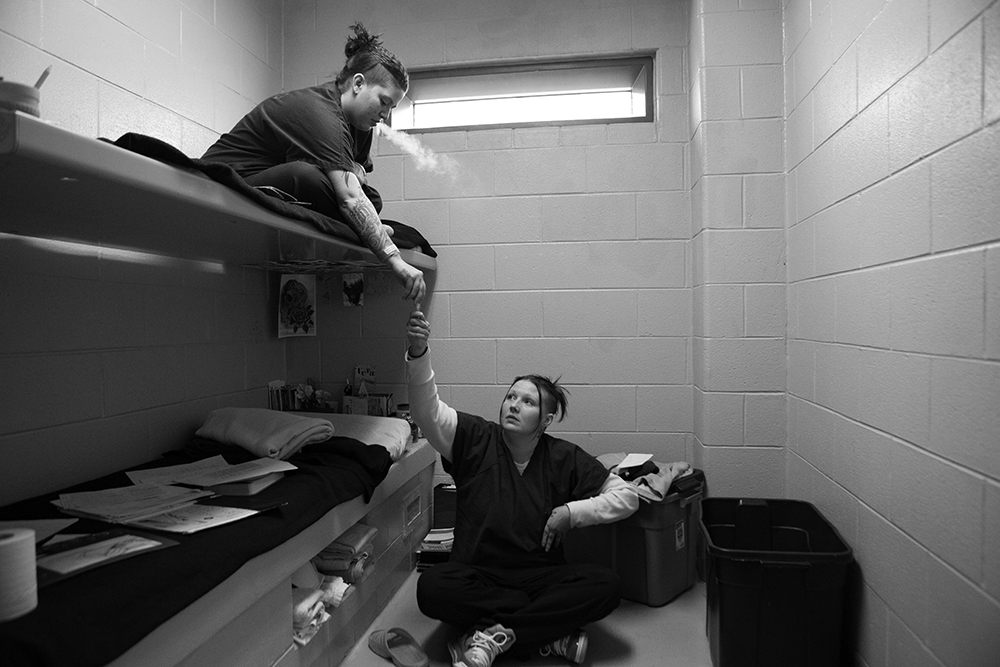

©Julia Rendleman, Deputy Celeste Walters talks with Stephanie Crowder about the problems she has seen with her behavior in HARP. Stephanie has resisted her “pull-ups” or consequences like cleaning the cell block. “It’s not a punishment. You need to get your mind away from what you’ve normally been doing,” Deputy Walters said.

![Michelle Blanely (left) holds Stephanie Crowder's hand while she reads an "Impact letter," a letter written to herself from the perspective of her five-year-old son. "I'm scared for you Stephanie. There are fuckers out there who are going to give it [heroin] to you for free," Michelle said while Stephanie talked about her impending release.](http://lenscratch.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Rendleman-Julia_05.jpg)

©Julia Rendleman, Michelle Blanely (left) holds Stephanie Crowder’s hand while she reads an “Impact letter,” a letter written to herself from the perspective of her five-year-old son. “I’m scared for you Stephanie. There are fuckers out there who are going to give it [heroin] to you for free,” Michelle said while Stephanie talked about her impending release.

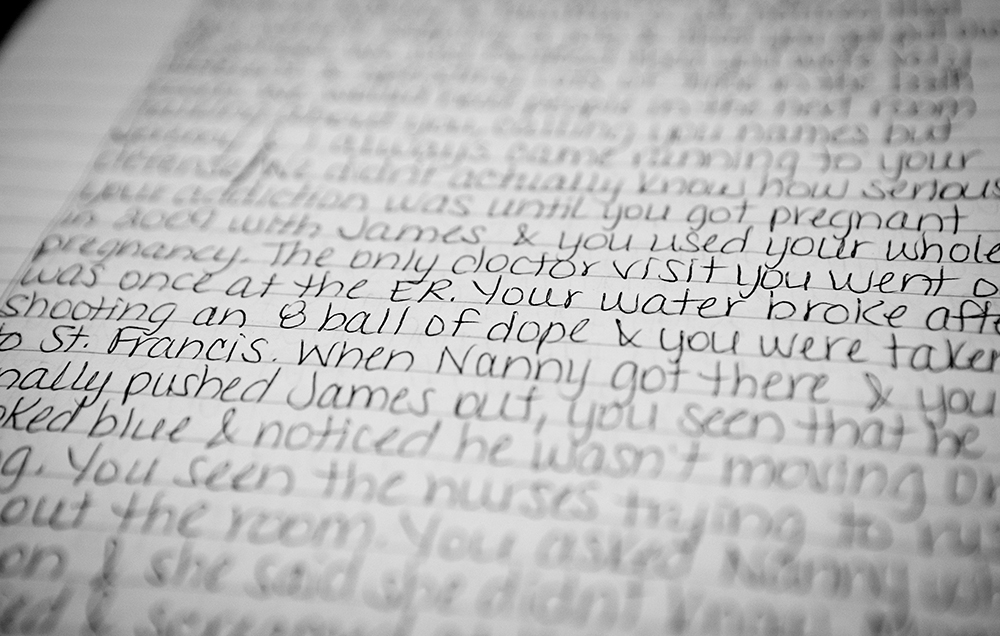

©Julia Rendleman, “Your water broke after shooting an eight ball of dope and you were taken to St. Francis. When Nanny got there and you finally pushed James out, you seen that he looked blue and noticed he wasn’t moving …” Tera’s “impact letter” written from the perspective of her oldest son recalls the birth of her third son, James, now 7. James was born at 7 months old, very sick and addicted to heroin. He barely survived, staying in the NICU for months. As he fought for his life, Tera would visit the hospital, shooting heroin in the parking deck before coming in to see him.

©Julia Rendleman, After weeks of worry, Tera Crowder reads her “impact letter,” a letter written from the perspective of her oldest son to herself, to the group December 1, 2017. “We just noticed you were very different and spending a lot of time in the bathroom,” her letter read.

©Julia Rendleman, Deborah Crowder, 54, holds her youngest grandson, Jaydian, three-months, at a friend’s house in early November. Deborah has custody of her oldest daughter, Tera’s four children. Jaydon was born while Tera was in jail. She held him for two days before turning him over to the nurses who turned him over to her mother.

©Julia Rendleman, Tera Crowder hugs her son James, 7, during a special face-to-face visit Thanksgiving day at the Chesterfield County Jail.

©Julia Rendleman, In January 2020, Tera Crowder visits her sister Stephanie at a family visitation night at HARP.

©Julia Rendleman, On New Year’s Eve 2019, Tera Crowder changes her youngest son’s diaper. Jaydian, 2, was born while Tera was incarcerated. “I had him with my ankle cuffed to the bed while a Riverside correctional officer watched. I got to hold him for two days,” she said. Tera touched her son again for only the second time when they reunited in 2019.

After spending 18 years as a public defender, Sara Bennett turned her attention to photographing women with life sentences, both inside and outside prison. Her work has been widely exhibited and featured in such publications as The New York Times, The New Yorker Photo Booth, and Variety & Rolling Stone’s “American (In)Justice.”

Like the women she photographs, Bennett hopes her work will shed light on the pointlessness of extremely long sentences and arbitrary parole denials. To bring Life After Life in Prison, The Bedroom Project, or Looking Inside to your community, please contact her. IG: @sarabennettbrooklyn

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anastasia Tsayder: ARCADIAJanuary 28th, 2026

-

Ed Kashi: A Period in Time, 1977 – 2022January 25th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Kevin Cooley: In The Gardens of EatonJanuary 8th, 2026

-

William Karl Valentine: The Eaton FireJanuary 7th, 2026