Photographers on Photographers: Brandon Ng in Conversation with Ed Greevy

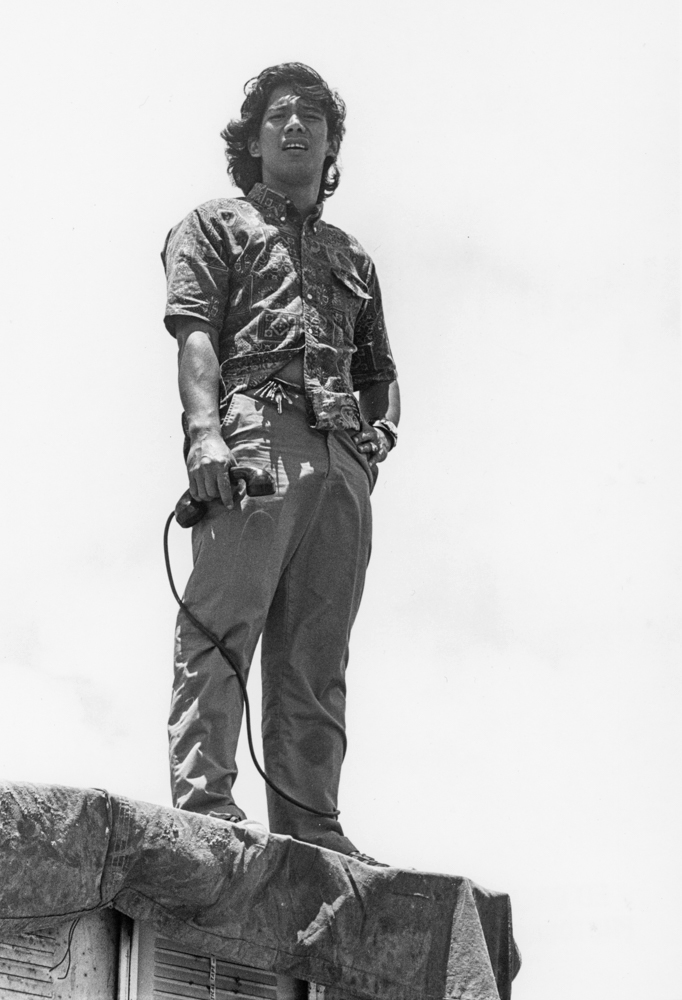

For most people, the mention of Hawai’i evokes images of white sandy beaches, grass-skirt hula dancers, and tropical flora. And while one certainly can experience these things with a trip to the islands, you will find none of these in the photographs of Ed Greevy. Instead, what you will experience is an examination of a land and its native peoples riddled with a history of violence, oppression, and exploitation. Greevy first came to Hawaiʻi in 1960, the year after its status change from US territory to the 50th state. Drawn here by the desire to surf, Ed quickly realized that the simple act of riding waves could not escape the upcoming struggles for land brought about by US statehood. Finding himself in the middle of rapid urban development and a transition from an agricultural to a tourism-driven economy, Greevy focused his camera on those most affected by these desires, Native Hawaiians and their land. The result is thousands of photographs spanning over three decades, illuminating the most pressing social and political issue of the times. Images of demonstrations opposing evictions of Kalama valley and Sand Island residents, military occupation of Mākua valley and Kahoʻolawe, and marches commemorating the 100th anniversary of the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy are all fixed into negatives of Ed Greevy; ready to view for those who are willing to observe. I first discovered Greevy’s photographs during my undergraduate studies at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

I had recently moved home from the American continent to Oʻahu, and, as most 20 something-year-olds do, I was actively reevaluating my positionality. Seeing Edʻs photographs for the first time was an education, one I always knew I needed but never knew what it looked like or where to find it. And while it’s easy to become angry about the injustices depicted in these photographs, I believe there’s more to be gleaned than disillusionment. Through his images, Greevy manages to capture the enduring strength and resilience of the people he photographs. He honors them; in doing so, Ed calls attention to a beautiful struggle and presents the virtue of a people and a culture. Struggle over land persists in today’s Hawaiʻi. TMT on Mauna Kea threatens the ecological stability of the sacred mountain, while rapid urbanization sees housing prices soar beyond the means of most residents. In times like these, Ed Greevy’s images remind us that there is still work to do. And the power resides in the hands of the people who do the work.

Ed Greevy (b. 1939 Los Angeles, CA) is a documentary photographer living in Makiki, Oʻahu, Hawaiʻi. His work is instrumental in archiving the sociopolitical struggle in Hawaiʻi from the 1970s through the 2000s. Many of his photographs have become synonymous with the Hawaiian sovereignty movement of the 60s and 70s. He also is responsible for making iconic images of Kanaka Maoli cultural leaders, including the late poet, professor, and organizer, Haunani-Kay Trask. Much of his oeuvre is present in his book Kūʻē: Thirty Years of Land Struggles in Hawaiʻi. While Greevy considers himself retired, he still does his best to make it out to demonstrations when he can. His work will be on view at the Honolulu Triennial in 2022.

Brandon Ng: When did you discover photography, and what’s your first camera story

Ed Greevy: In high school, I was a small jock who observed that the school’s photographers worked in near obscurity. At that time, I wanted a good camera but could not afford these tech marvels. I had discovered surfing while in Honolulu for a semester in 1960. After surfing most of 1963 in Hawaiʻi, I went to Japan for the potential purchase of a “good” camera, as I wanted to become a surf photographer. I did not know one Japanese camera from another. So I went to several Tokyo shops to educate myself and learned the best affordable Japanese cameras were Canon and Nikon. Nikon made the most appealing telephoto lens, so I bought a Nikon F with a 500mm F. 5.0 lens. I still have both.

BN: How did you begin photographing land disputes in Hawaiʻi?

EG: In about 1971, I got a letter from a surf magazine editor in San Diego asking about Save Our Surf (SOS). The next day I saw a one-of-a-kind poster in what was a camera store window in Waikīkī. The sign informed the public of SOSʻs resistance to the state’s plan to put sand for tourists over “Baby Queens” surf site, just a few yards from where I first surfed. Seemed to be a bad idea to me. I went to an SOS meeting at John and Marion Kelly’s home that started a long and continuing relationship with SOS. After preventing many surf site destructions, John Kelly told the group he was going to assist renters from 1970’s evictions, and all were welcome to help tenants.

BN: What was the driving force for practice through your years of working?

EG: My father was a carpenter who always taught me to support the underdog. I hope my photography work has helped them.

BN: What is the responsibility of the artist/photographer whose work centers around issues of social justice?

EG: First, one should decide which side you are on. In my view, no one is unbiased, although many in the news reporting business claim to be neutral. We are all human and have our biases. After deciding if you favor powerless people or people/institutions with power, don’t hide it. Be straight.

BN: How do you define success?

EG: Success as a photographer is the most difficult to answer. Probably, from my perspective, helping powerless people resist forces larger than themselves.

BN: Who are your photographic influences? Who are your non-photographic influences?

EG: I’ve always liked the work of W. Eugene Smith. I learned a lot just by studying his pictures. I also responded well to images by Edward Weston, Paul Strand, and later, Sebastiao Salgado, who had a major print show at the old Academy of Arts (now Honolulu Museum of Art). Locally I like the lifetime work of Franco Salmoiraghi and PF Bently. I also learned a lot from my mentor, John Kelly.

BN: Any advice for young photographers?

EG: Get the best camera you can afford and shoot a lot of what interests you.

Brandon Ng (b. 1984, Honolulu, HI) received his BFA from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa (2012) and his MFA at Arizona State University (2020). Ng’s work investigates the intersections between place, persona, and positionality. His photographic and installation works deconstruct historical narratives to examine social systems that are exclusionary and oppressive. Being a product of settler colonialism in the Hawaiʻi, Ng is particularly partial to policies that affect contemporary social and cultural issues of Oceania and their overlap with the United States. Recently, Ng has been investigating how to use the camera and lensless image-making processes to create installations and photographic gestures to catalyze the unlearning imperialist methods that impact Hawaiʻi and its people. Through this process, he considers ideas concerning hybridity and how to make colonized spaces into decolonial places. Ng’s work has shown in Hawaiʻi and the continental US, including exhibitions at the Honolulu Museum of Art, Shangri La Museum of Islamic Art, Culture and Design, and Northlight Gallery in Phoneix, Arizona.

Follow Brandon on Istagram: @b_kh_ng

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anastasia Tsayder: ARCADIAJanuary 28th, 2026

-

Ed Kashi: A Period in Time, 1977 – 2022January 25th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Kevin Cooley: In The Gardens of EatonJanuary 8th, 2026

-

William Karl Valentine: The Eaton FireJanuary 7th, 2026