Photographers on Photographers: Harrison Huse in Conversation with Richard Renaldi

For the Photographers on Photographers series I wanted to interview Richard Renaldi. I use my camera as a tool to talk about social issues and communities; to let their voices come through the images. Renaldi’s work brings light to communities and the use of portraiture allows for striking images while also creating a dialogue about the subjects he’s photographing. To get to talk to him while still trying to figure out myself as a photographer is such an important opportunity I was honored to be part of.

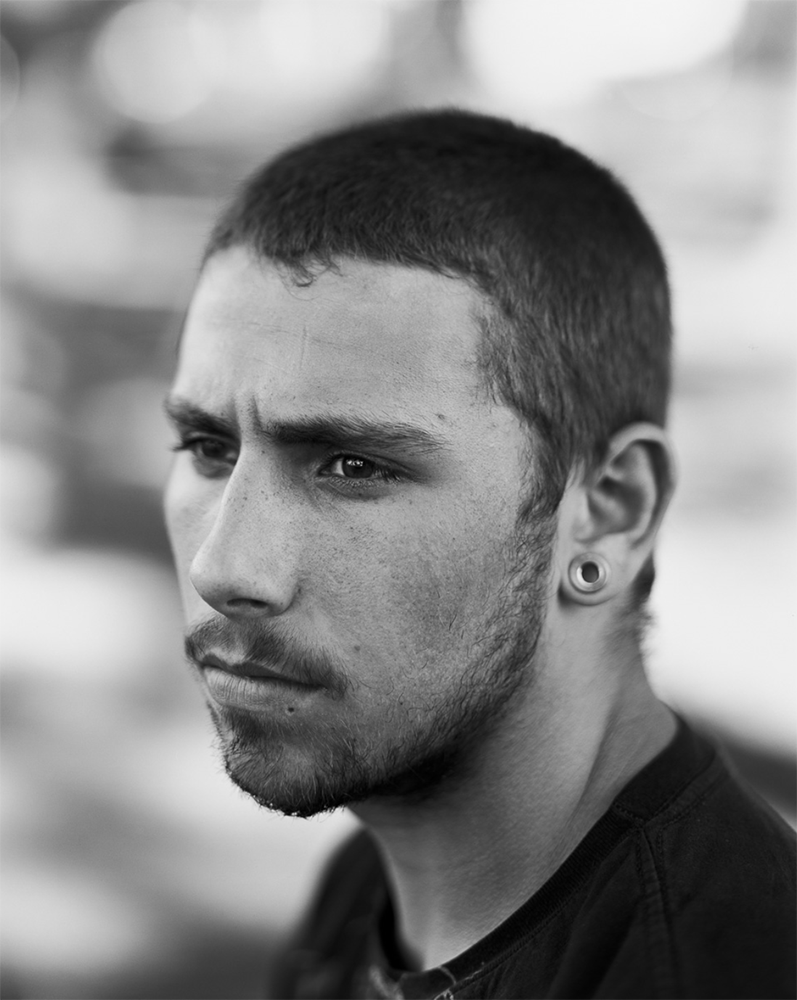

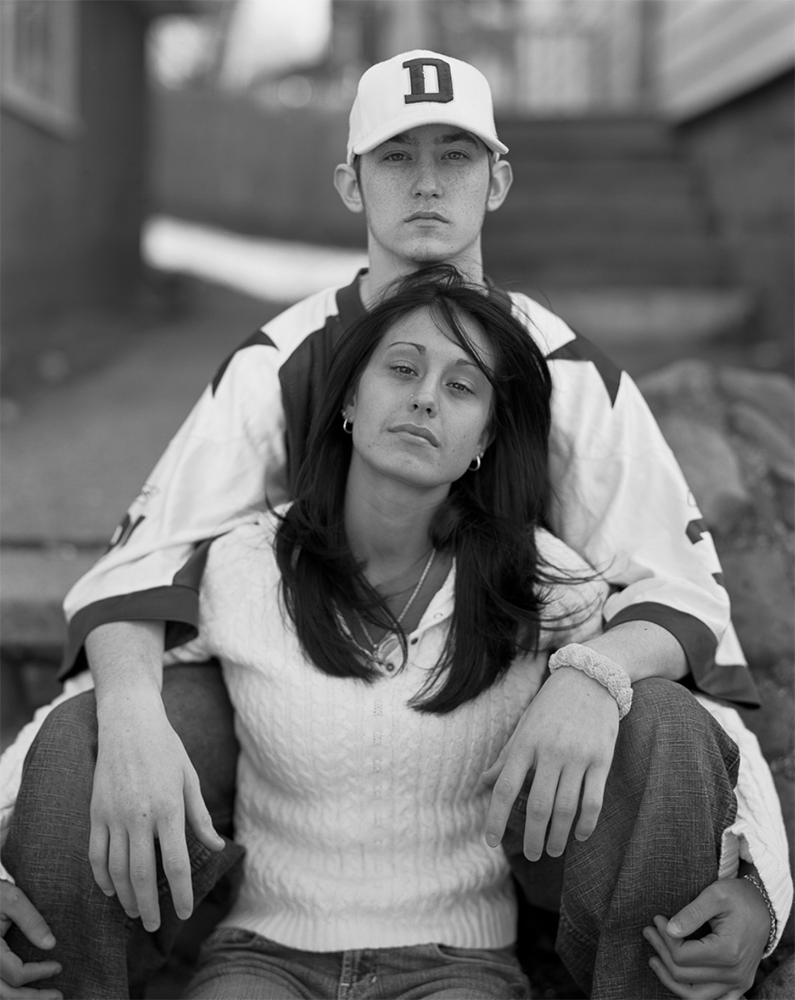

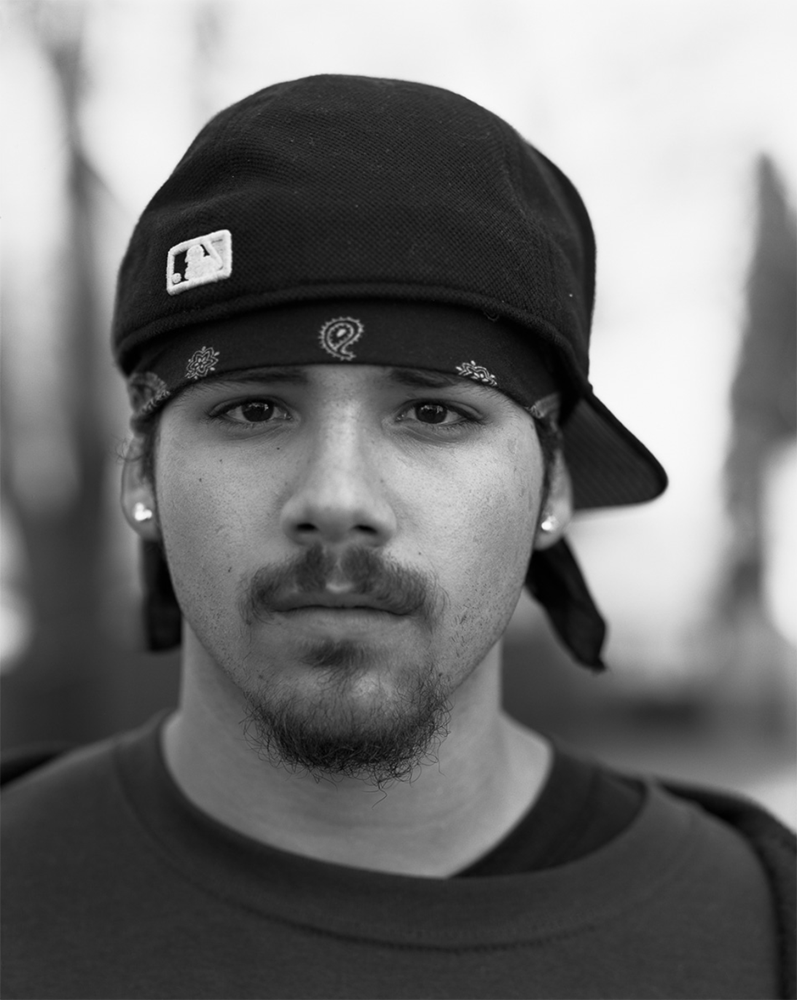

Richard Renaldi was born in Chicago in 1968. He received a BFA in photography from New York University in 1990. He is represented by Benrubi Gallery in New York and Robert Morat Galerie in Berlin. Five monographs of his work have been published, including Richard Renaldi: Figure and Ground (Aperture, 2006); Fall River Boys (Charles Lane Press, 2009); Touching Strangers (Aperture, 2014); Manhattan Sunday (Aperture, 2016); I Want Your Love (Super Labo, 2018). He was the recipient of a 2015 fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

Harrison Huse: Hello Richard, it is such an honor and privilege to get to talk to you today. Thank you so much for being part of this and letting me have the opportunity to get to interview with you today.

Richard Renaldi: No problem

HH: So, a good starting off point that I’ve been curious about is how did you get your start in photography?

RR: I started in high school, because I wanted to take art and it was closed, it was full, so the art instructor suggested I take Photo. I didn’t have a camera but my sister did, so she let me use hers; and for the rest of my career now she basically claims what limited success I’ve had.

HH: My father does the same thing. When I was in middle school he gave me a point and shoot and ever since then I’ve progressed to where I am.

HH: So your work mostly centers around communities of people and their stories, how do you find what subject or community to photograph and work with?

RR: That’s a good question; it’s always kind of happened organically, because the things I ended up focusing on often intersected with my own story, whether it be my first serious project right out of NYU was to photograph the queer scene from like 1993 onwards. So I did that like, really intensively for 3 to 4 years and that was obviously informed by my own identity as a gay person and feeling the sense of community there; this was also just a place I hung out. From there it just led to other work, like, the next project project I did was of wealthy people on Madison Avenue in New York. It kind of grew out of my previous project in a sense because they’re both really microcosms in New York and in both groups, fashion was a way to gain access to status in each of those groups, and often it was interesting because the gay, white, black and latino kids were in a way emulating the wealthy fashion houses that were located on Madison Avenue. I didn’t see that at the time really but it really was like two pieces of the same puzzle that fit really well together if you were to map out my interests. So that wealthy population led me to think more about class also and I grew up a pretty privileged rich kid in Chicago and I went to school with kids who lived in the ghetto from like, Cabrini Green, like Chicago is really segregated and Cabrini Green was blocks away from the Gold Coast where I grew up. So, class was always something I was super aware of and the inequities of our society and so I think Madison Avenue… and also in high school I got really active in the Young Communist group and I really started thinking about class and learning about socialism and I really think that had impacted my thinking about how I saw the world and how I saw people, the communities. Then I just started doing so many different projects and those things, like, gender, identity and class really informed much of my work; to this day even. You know, I, kind of came back to the more queer work in the mid 2000’s like when I did my Manhattan Sunday project, photographing night life, which was, again, based on my own experiences as a nightclubber and wanting to tell that story and then it got even more personal when I did like my autobiography when I went way back to more like not so much large format formal work but looser, more, you know, point and shoot, 35mm freestyle kind of way and now I’m just doing them both.

HH: As someone who’s currently working on a long term project, myself, how do you find ways to keep your interest in whatever subject matter you are working with over long periods of time?

RR: Like, again, I’ve been doing the hotel room series of portraits with my partner, Seth for twenty two years and it’s interesting because we like to travel or we are traveling, away from work and it’s like, “Oh, well let’s do this portrait”. I think I tend to gravitate towards things that I don’t get bored with anyway or projects that end up kind of like… I’ll try something and, like, I started this thing on gamers and magic the… whatchamacallit… that card game… so you know I realized I wasn’t that interested in it and I quickly gave up. I did like two shoots and said, “OK”. So, you kind of know… Magic The Gathering… You kind of know if you want to keep doing it, that can hold you into the project; but you also have to start listening to the work. If you start making the same picture over and over again it’s kind of a hint that maybe you are exhausting the options for ways to tell the story. I think working towards a book in a final format or for a lot of artists it’s an exhibition; but working towards some kind of final… nothing’s ever, “final ” final… but a working “final” presentation helps you also define what pieces you need and what you have already gotten overall from the project. Then you kind of finish it and it’s almost like having a kid, I think, metaphorically, like you put it out in the world and then it’s no longer, you know, it’s kind of like having an empty nest, you feel a little sad that it’s over and then you’re able to just, see what happens to it and watch it either grow or flop, yeah that’s how that works.

HH: How do you find inspiration in your creative practice?

RR: I’m inspired by, like, I think… I’ll just go to the park and just watch people. I find people, generally, inspiring, especially living in a big city where there’s so much diversity and so many different kinds of people. I still get literally thrilled, I mean I was in Washington Square Park, two or three days ago, I was just sitting there for an hour, looking at everybody, I was just feeling great. I didn’t have my camera with me, I didn’t take any pictures that day, but it was just lovely; it was a nice spring day, everyone was out. I get inspired by the creativity sometimes that people put into their appearance and how they kind of peacock, or display themselves to the world and when they put some thought or creativity or delightfulness into it, I’m drawn to that. Sometimes when I stop someone to photograph them, I’m celebrating that. I think I get inspiration from the books I read and the films I watch and the art I go to look at. Sometimes through my colleagues, I find inspiration through what they’re doing. When I come across a really great concept I feel really happy when someone’s done that. It comes from multiple forms, I don’t feel like there’s, at least in my life, fortunately, I don’t feel like there’s a lack of inspiration; if anything it feels like there’s too much inspiration. I think that I, hopefully, still… You know it’s been a long time since I started photographing, like thirty six years. I still feel like, hopefully I have something to say that’s interesting, because if you don’t then that’s one place to start doing something else, or to help someone else doing it; or you could do both at the same time. I’ve said a lot already, maybe I need to help other people get their stuff out or help them say something and I think that in some ways is where teaching would really be part of my practice. I’ve been doing a lot of teaching lately, I’m up for a position this fall too. That is another way that can be passing along inspiration, hopefully I’m inspiring someone through this, the way a teacher is with artists, and help the people that inspire me.

HH: Piggy-backing off of inspiration: What advice do you have for someone who’s fresh out of college and trying to make their own path into the art world?

RR: Oh boy, my advice is give up; the art world is horrible. Of course it’s not horrible if you’re doing well but the point is that there’s a sliver of space for people who can do that. That sliver, let’s say is the length of the computer screen here, this is all the artists and that little space is like a small line between you and me right now on my screen (the distance between our video camera screens on zoom.) In that space what’s determinative about who gets in that space isn’t necessarily, “excellence” or “people who have something to say.” It’s some of that, but it’s also a lot of like, just the bullshit, like who you know, right timing, following a trend in art and hitting it, random, total random luck, academia, blue-chip kind of petogry like the Yale MFA people; and that’s not even true for all of them. So that middle space is so thin and if you can make it in that space take what you can get out of it because that space is very much tied to a very equitable system of global capital and that has been earned by a one percent of people, primarily. Now there are other people that buy art and collect art because they love it and they probably don’t have a ton of money; they’re my favorite kind of collector. But by and large it is really tied to capital and capitalism. It’s inherently a system that is full of inequities and is built on a lot of exploitation; so that needs to be remembered. The institutions that support artists are supported by that system of inequity. The big museums are all built on the wealth of the gilded and the 1 percent; it’s all about class. It’s all sort of problematic. So that’s like a critique of that. Advice about how to make something in the art world. They like to sometimes flirt with social critiques. I think in the last 5 years an enormous amount, maybe not as much as there should be but a lot of opportunities open up to people of color. I think that that’s great, I don’t trust the art world to deliver in rectifying those inequalities. I think the artist has to force them to and I think that with this younger generation is pushing and I think that’s great. One piece of advice is to keep on pushing. Another is to understand what system it is that you are trying to basically ask for the keys to enter into and what that’s built upon because I think there should not be any illusions going into it. I think that the best advice is to be able to function and wear multiple hats. An artist or photographer needs to do many different jobs to make a living. The more broadly your skills are, in some ways I think, are more suited to the economic conditions for an artist to survive. But in the end, the best advice is also to really just, in the time you have that can be used to make work is to make work; and to really continue to make the work that you need to make that comes from a place of authenticity, from yourself and your story. I think that’s the best advice that I can give.

HH: When you were out of school how did you find your first break?

RR: Well, as well as an employee, I got a job as a photo researcher at Magnum Photos; so I worked in the archive from the fall of 91’ to 95’ or 6. That was great because I got to continue my visual education and I got to work with some pretty respected and talented artists in the field, photojournalists and so forth; kind of the “who’s who” of Magnum people from that era; though I was just kind of an underling. Then I started working in another agency which was a leftist photo co-op; very aggressive and socially concerned photo co-op. As a staff member you could also be an archive member so I started actually to photograph a lot for the archive. Photo stock photograph a demo, just like everything, the A-Z in life. That really gave me the confidence, telling myself you should really try to be a photographer instead of just working as a photo researcher. I slowly transitioned out of that and around 98’ I left the agencies and started doing editorial work. I started working on personal work, which is how I met my partner Seth; who had an 8×10 view camera. That’s when I fell in love with it and I kind of adopted it and held it hostage from him. It really opened up another way of seeing and shooting that I think then resulted in new opportunities to like make those Madison Avenue portraits that I made with the view camera. I was shooting 35mm at the time and switched to shooting in large format, so that was kind of a big change in my work. With that work I started thinking, “This is something, there’s something here.” I had tried to publish the work I was shooting at the time that I had put a book together in the late 90’s. I took it around to dozens of publishers and everyone said no. I felt discouraged but it didn’t discourage me from continuing to make work. Then I showed the Madison Avenue work to a curator at the ICP (international center of photography) and he included me in their photo tri-annual. At the same time as that I found it gallery Chelsea that I went to an opening and I learned the gallerist lived right around the corner from me so I kind of connected with him and pursued that avenue as sort of like, “Could I show you my work some day?” That all kind of helped gear me toward thinking of myself differently, like I could be an artist that shows his work in galleries; even though I haven’t really sold much work, ever. I mean I sell a little bit; it’s always a little bit so that’s why it’s not sustainable for most people that have shows they don’t sell out their shows. Again,the problem in photography is that you are working in a system that is kind of allergic to the idea of multiplicity, like printing a negative that can be printed ad nauseum, for infinity. The art market doesn’t want that at all, they want you to dead, ideally, because then your work is more valuable. Other than being dead they want a one of a kind. That’s why you’ll see over the years, if you’ve been aware of certain photo galleries, they often will make a switch to start showing manipulated, single, photos processed in sea water and all that kind of stuff; because it becomes a unique object rather than just a print. They force on this thing of editioning so that you can only have x number of one thing. Which it’s just so funny because inherently it’s a contradiction to the inherent nature of the technology itself; so that’s always a good intention. I used to go to this gallery here in chelsea and I got to know the gallerist there and he was on my email list. One time I took this picture of a very beautiful bull rider named Mike Lee he was on the email list. The gallerist told me he had a bunch of people who wanted to buy it, and that started a relationship with the gallery. That’s how I got my foot in the door there at the same time I was working on more projects and working on the project Fall River Boys that I want to get published. I was able to get that in front of the editor at Aperture, who actually knew of my work because of something I contributed to this public project for the global AIDS pandemic that I did with the Columbia University School of Public Health. So just like a strange intersection and more opportunities came in 2006 with Aperture. That would be the largest contributing factor to the reason you and I are talking today. Like figuring out me and what put my work out there on the map it expanded me as well as my audience. Then Touching Strangers, again, that was a project I did from 2007 to 2014 and there was a news piece done by CBS. They tailed me on a shoot and did this pretty lovely little three minute segment, then that ended up going viral. The whole Touching Strangers thing went viral multiple times. So for a while that expanded my audience, that was pretty fair weather on that count because I think that a lot of people came to me just for that. Even if they hadn’t seen any of my other work, which is fine. Touching Strangers is gonna be the biggest thing I’ve done that had been seen by the most people, like that will be my apex. I don’t think it’s necessarily the apex of my creative life. But that was kind of an offshoot in my experience of what I think a normal artist’s trajectory is.

HH: So last question throughout your career, how do you define success for yourself?

RR: That’s a terrific question. I think that if you’ve been honest with yourself and honest with the audience and worked hard and been thoughtful. And maybe… I don’t want to say contributed… and just that you… I mean it’s such an arbitrary… like, success, what does it mean? And what is successful for myself? I mean in many ways I’ve been a successful artist, I’ve had 5 monographs of my work and had shows in museums and galleries pretty far and wide. I think the most exciting thing if I could crystallize it is when I’ve done a bunch of shooting and if it’s negative film and I get the negatives back and I’m scanning them and then seeing them on the screen and I see them and it’s something I’m really pleased with; that’s the most wonderful feeling. To see that picture like, come up on your screen and to be like, “Oh I love it! I love how it came out!” and just feeling so… It’s a collaboration if it’s a portrait, but whatever it is you know you made it and you nailed it. Something that all the wonderful combinations that make something meaningful or beautiful all kind of comes together. I often think of those pictures of something going on, when you’re able to see it come to life; there’s just something so lovely. It’s nice to hear people, to have fans, to have people say, “I love your work and I love what you do.” That’s beautiful and I really appreciate that because it’s nice to be liked, obviously. It’s nice to have people respect you for something you’ve done. It’s interesting because it’s random, like some people gravitate towards one body of work and some people like something else I did; I love that. I think I’m successful in many ways because I think I’m admired by my colleagues and by the grass roots of the young people. I know a lot of people teach my work and I think a lot of young people like my work and that feels absolutely great too. I think I have a good relationship with good friends and good securities that help me have that sort of feeling. I also have chemical down days and you know, some health issues, nothing bad. So this as much as someone on the outside might see as success, but they still have to clean the shit out of their toilets. Building on that, I think that having heroes and idols, like, it’s great to admire people and it’s great to be inspired by people which we talked about in your previous question. I think that when you valorize someone it’s really dangerous. I think we shouldn’t put people on pedestals; I don’t think many people put me on a pedestal, which is good. In general I just think, often, our heroes will let us down. Like we keep finding out every other week that someone we thought was one way was actually the other, which is kind of horrible. So I think that kind of rounds out your question and I like how it touches back on the inspiration question.

HH: Thank you so much for your time and giving me these fantastic answers; I really do appreciate it!

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Hugh Kretschmer: Plastic “Waves”April 24th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Richard Lloyd Lewis: Abiogenesis, My Home, Our HomeApril 23rd, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Jason Lindsey in Conversation with Areca RoeApril 21st, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: J Wren Supak in Conversation with Ryan ParkerApril 20th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Josh Hobson in Conversation with Kes EfstathiouApril 19th, 2024