Photographers on Photographers: Tristan Martinez in Conversation with Jason Fulford

Every August, we run a month of photographers interviewing other photographers, but this year we reached out to our 2020 25 Photographers to Watch and asked them to interview a photographer who has inspired their journey–a hero or a mentor. Today we share Tristan Martinez‘s interview with the iconic photographer, Jason Fulford. Follow along this month for wonderful insights and interviews. – Aline Smithson

I first came across Jason Fulford’s work one of the many days I was in the library while attending The School of the Art Institute of Chicago for my BFA. I fell in love with his book Hotel Oracle, and must have had the library’s copy for a whole semester while I flipped back and forth from text to image trying to make sense of the story being laid in front of me.

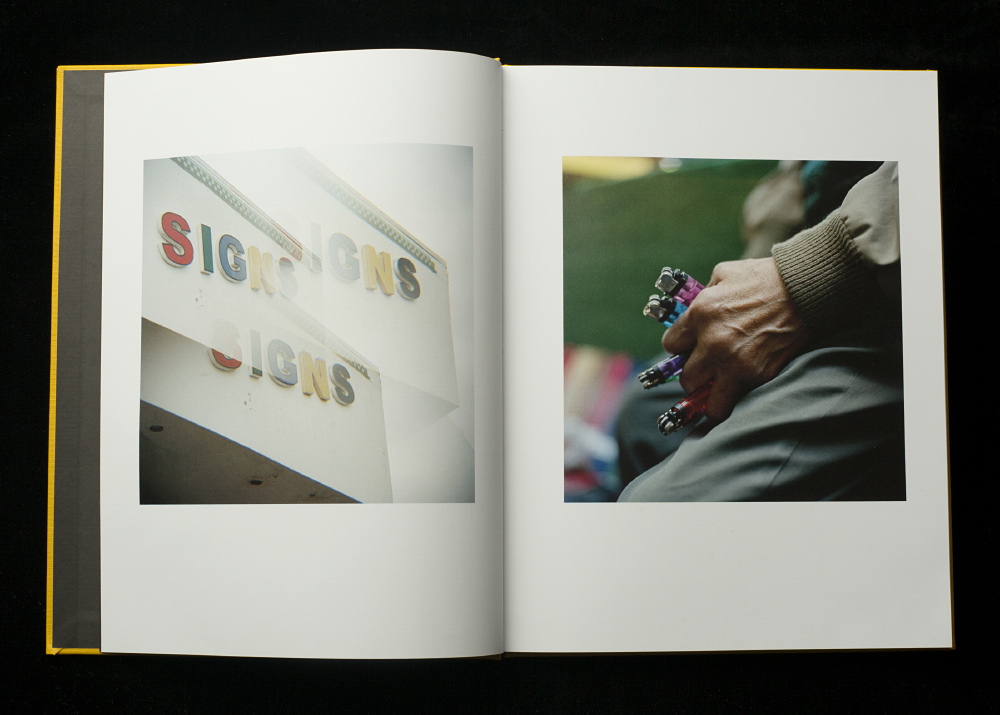

Jason’s work is made with such a calculated ease, leaving the viewer with an open ended narrative that is left up to you to make sense of. With each body of work there seems to be a new game to be played, I’m always very excited to play that game.

I am excited about the opportunity to interview Jason and pick his brain about what inspires him to keep making and how he deals with the ambiguity in his work. When navigating my own exploration into the world of photography, Jason’s work helped me dive into sequencing, the power of the book format, and the fluidity in ways to conceptualize work.

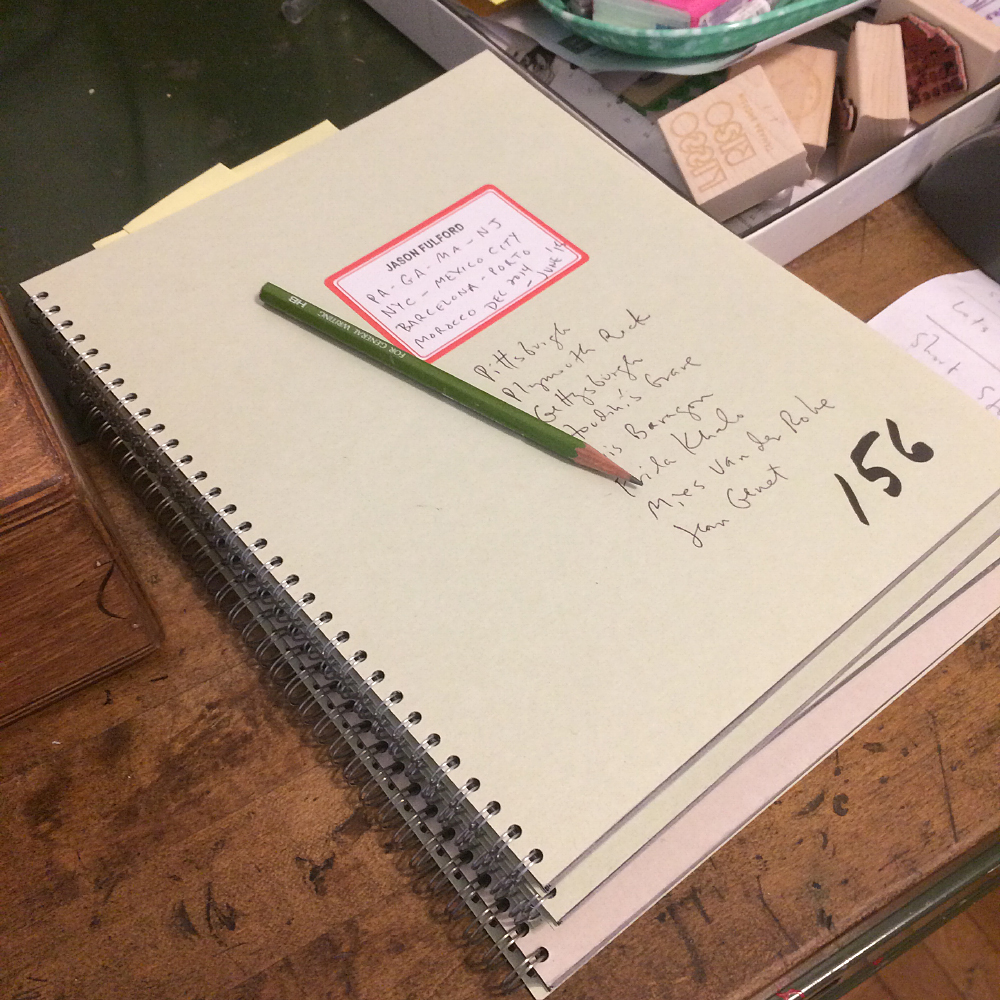

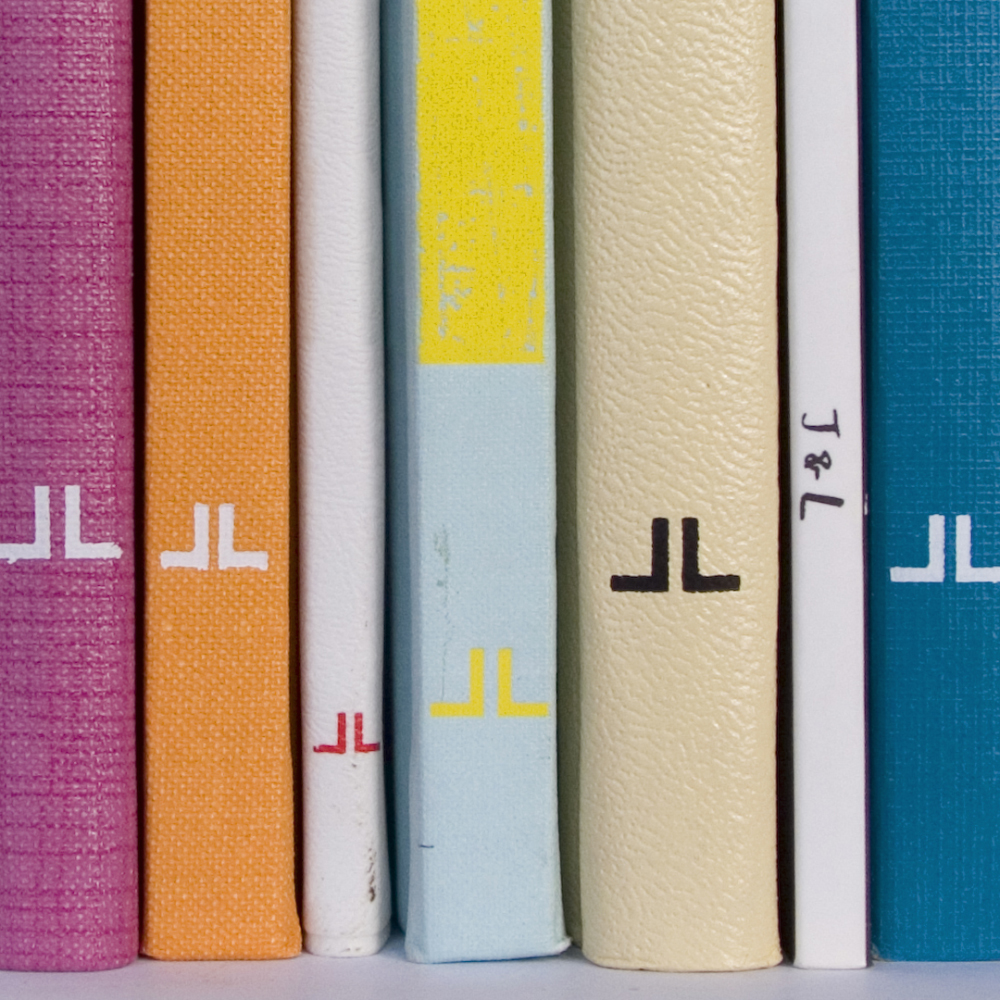

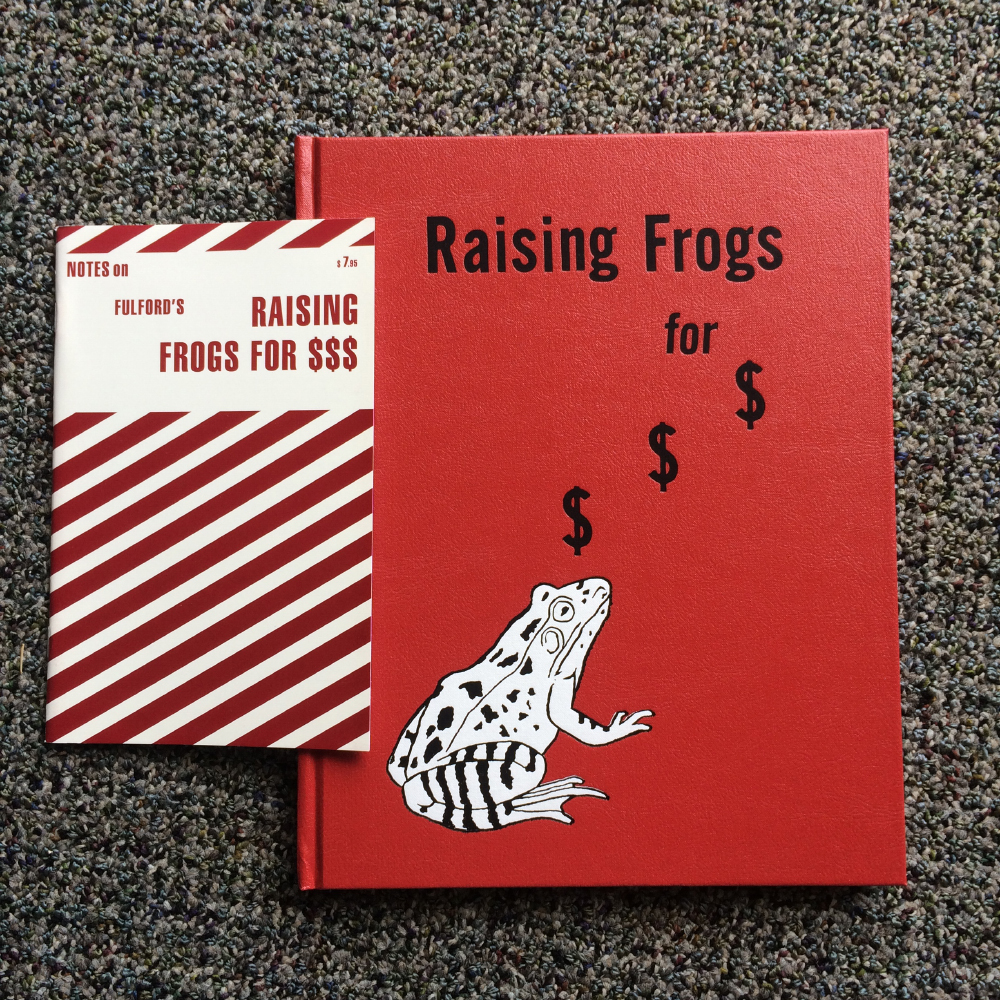

Jason Fulford is a photographer and co-founder of J&L Books. He is a Guggenheim Fellow, a frequent lecturer at universities, and has led workshops across the globe. Fulford’s photographs have been described as open metaphors. As an editor and an author, a focus of his work has been on the subject of how meaning is generated through association. His monographs include Sunbird (2000), Crushed (2003), Raising Frogs for $$$ (2006), The Mushroom Collector (2010), Hotel Oracle (2013), Contains: 3 Books (2016), Clayton’s Ascent (2018), The Medium is a Mess (2018) and Picture Summer on Kodak Film (2020). He is co-author with Tamara Shopsin of the photobook for children, This Equals That (2014), co-editor with Gregory Halpern of The Photographer’s Playbook (2014), guest editor of Der Greif Issue 11, and editor of Photo No-Nos (2021).

Follow him on Instagram: @mushroom_collector

Tristan Martinez: How are you!? Where are you/ what are you doing right now?

Jason Fulford: Hi, I’m in Scranton, Pennsylvania with my friend Jordan Stein. We are trying to wrangle a story—about a trip we made to India a few years ago, looking for some old watercolor paintings—into something that might make sense for an audience to read.

TM: Who are your top three artists/photographers/authors? Your choice on what you’d like to answer.

JF: That’s an impossible question. It changes daily, and in each conversation. I’ll just say that this morning I was listening to Don Cherry, looking at a drawing by Saul Steinberg, and reading Lydia Davis.

TM: What was your “Big Break”?

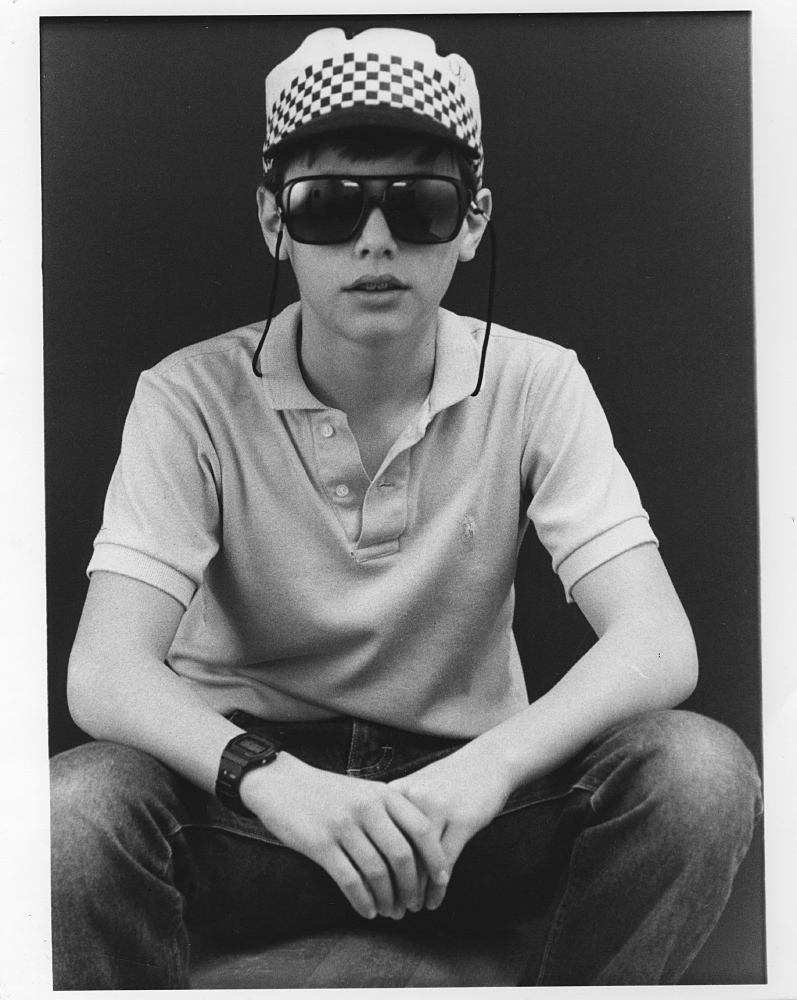

JF: I’ve had so many moments when someone stepped into my life at the right time, from my mom giving me a photo lesson at age 11, my high school art teachers, Miles Boyd & Jay Freer, challenging me, Pratt Institute giving me a scholarship, my boss, David Kucera, teaching me how to weld steel, another boss, Michael Rambo, teaching me about graphic design and pre-press, and meeting Jack Woody in New Mexico while hitch hiking—just the tip of the iceberg.

TM: How did you navigate editorial work outside of your personal practice? Were you persistent in emailing to get work? Or did magazines like Topic and The New York Times approach you? I have to add outside of the interview on a personal level to you, the images for A Dream Called Epcot for topic are amazing.

JF: I reached out specifically to art directors and photo editors whose work I liked. You want to work with people you admire. Then after your work is out there, people start to call you.

TM: I was fortunate enough to attend your artist talk in 2019 at The School of The Art Institute of Chicago while I was in undergrad. You mentioned in this talk that you consider yourself more of a collector of images. Is it fair to say that by collecting images from traveling, you are better able to conceptualize your next body of work, opposed to having a grand idea and going out trying to make images that fulfill those perimeters?

JF: Yes. One of the best pieces of advice I’ve been given was from Anne Turyn, who I studied with in college. She said, basically, “Keep shooting. Then look at the pictures and go make more. All the questions and answers will be in the pictures.”

TM: I know that you’ve said it’s helpful for photographers to get help when sequencing/ narrowing down image choices. Do you seek out help when sequencing or making cuts?

JF: I work on it solo, until I think it’s good, then I ask advice from a handful of friends who I know will be critical, including my wife Tamara.

TM: You didn’t get your MFA, do you think it’s crucial now as an emerging artist to hold both a BFA and an MFA?

JF: No. In fact many great artists come to photography from another field of study, or just from life experience.

TM: To you, what’s the importance of maintaining a photo practice that’s based in film photography opposed to switching to digital?

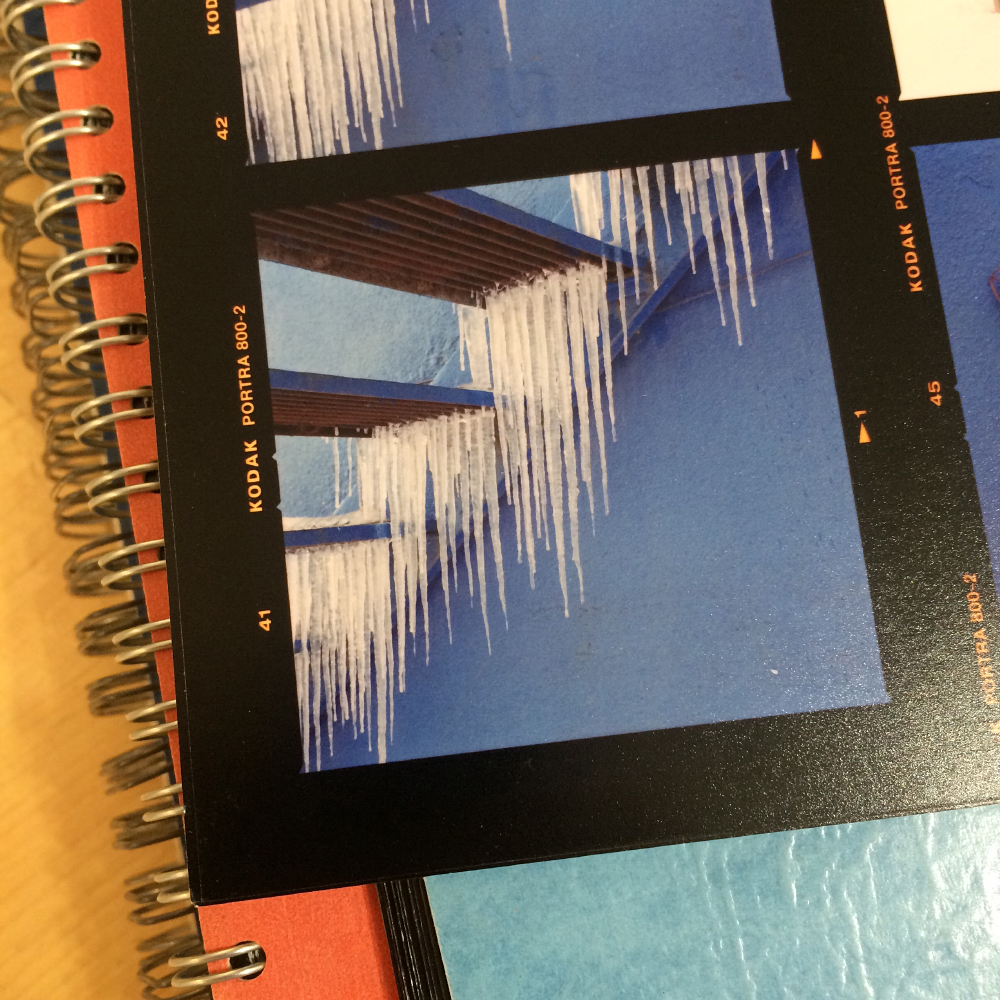

JF: I still love the process. I love the equipment. I love the patience and discipline. I love the surprise of seeing the contact sheets after having forgotten what I photographed. I love not obsessing with reframing the image while making the picture. I love the physical archive.

TM: Your work has a tone of ambiguity in it, you make the audience work for understanding and meaning. How do you accomplish this? What are some of the criticisms that you’ve received for being so open ended in your practice?

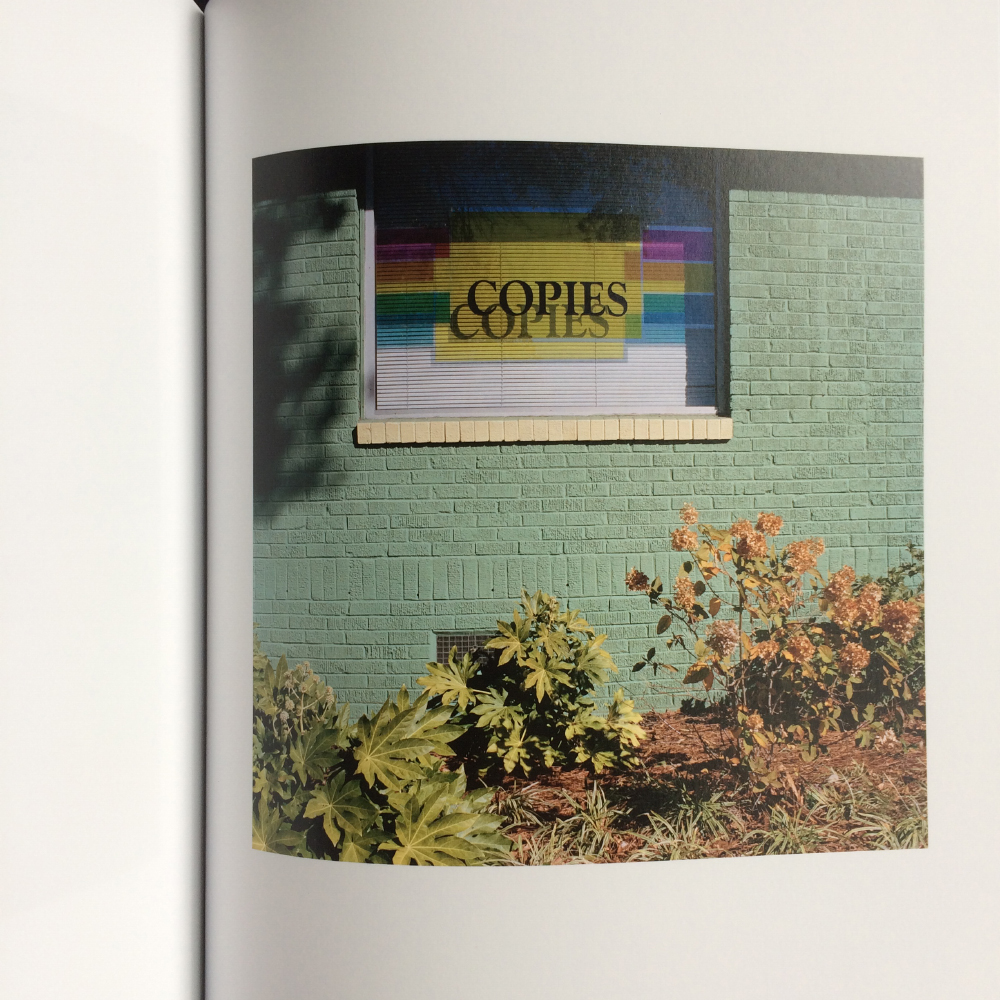

JF: Well, I also want to be surprised by the work, and if it’s too easily digestible or “explainable”, then it’s no fun to read a second, third, fourth time. I want to make work that keeps giving. Usually this comes together for me in the editing process, when I find combinations of pictures that fit well together in a way that I can’t explain. And then I sit on them for a while, and if they still inspire new thoughts, then they get “fixed” into place on the page.

One thing you might not realize is that when you make books, you don’t hear much feedback. The books filter out into the world, and you don’t know who bought them, or where. And most people criticize you privately, right? Behind your back. Occasionally I meet someone at an event or a book fair, who says, “I don’t get it.” Some people want answers—”What is this about?” Others like to come up with the answers themselves or enjoy the hovering quality.

TM: Do you seek out solo exhibitions? Do they come to you? Or do you prefer the book format and book release? Why is the book format opposed to the Gallery route? In your opinion is one better than the other?

JF: So far, the exhibitions have come to me. I mostly work in the book format. But the gallery/museum is also fun. It has a different set of rules than a book, and I love the challenge of making the walls come alive.

TM: Do you think photography has the capability to be represented in a gallery without objects/performances/sculptures around it to reinforce the photographic concepts?

JF: Yes, of course.

TM: How did J&L books come about?

JF: I self-published my first book, Sunbird, and showed it to my friend, Leanne Shapton. She said, “Cool, let’s start a publishing company.” So we started by editing work from our friends into books, and then submissions from strangers started to come in.

TM: Which of your books is your most prized work? and why?

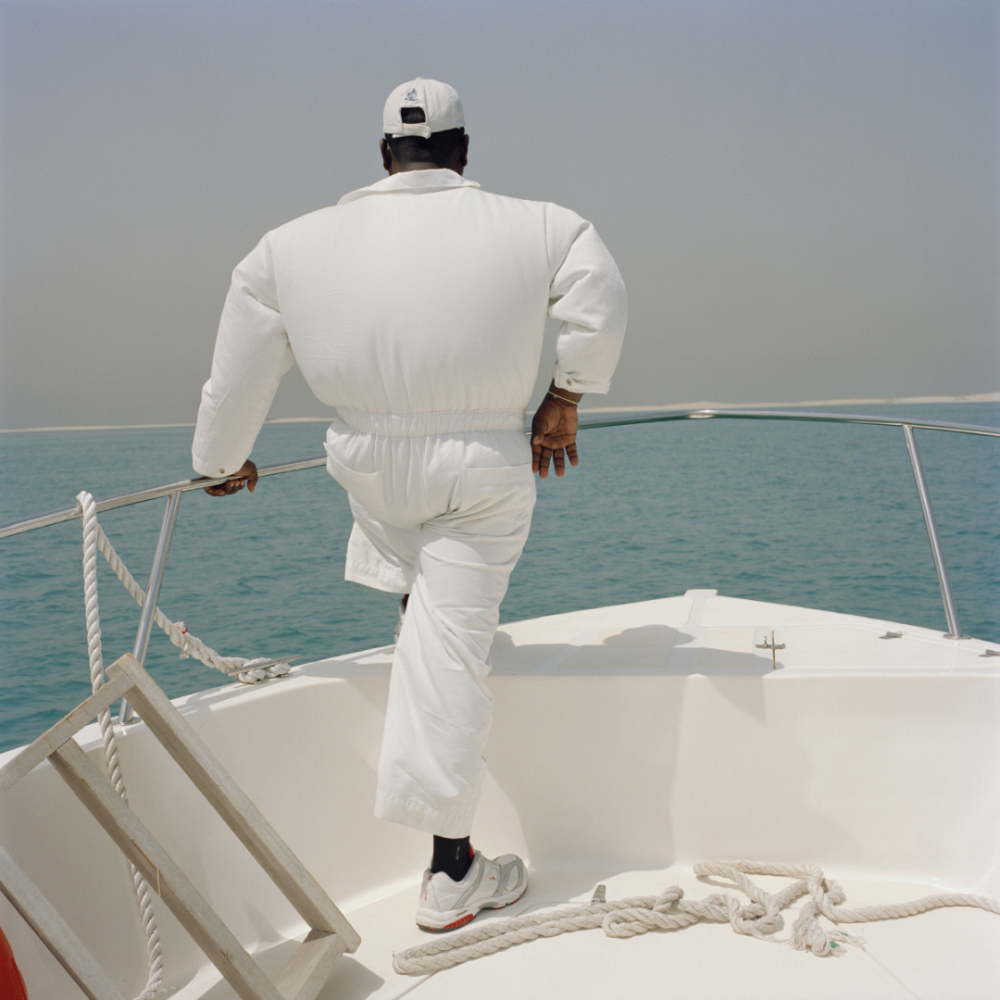

JF: Like, the “favorite artists” question, I can’t answer that. Each of my books has marked a phase in my life, so usually I’m most interested in the last one, or the next one. I’m still feeling the afterglow of Picture Summer on Kodak Film with an exhibition of work from the book that I just installed at Micamera in Milan, and I’m excited for Photo No-Nos to hit the shelves. I have four or five groups of pictures “in progress” that are starting to feel like they could be books. I just got back from 5 weeks in Italy—my first big trip since Covid lockdown, and I shot a lot of film. Some images will go into one project, others into a different one, and there are a handful of new pictures that I don’t quite understand yet, and I’m excited about those.

TM: How do you stay creative? Does traveling keep things interesting and inspiring for you?

JF: Yes, traveling keep me on my toes, and sometimes helps get me out of a rut. And I learn a lot from meeting people around the world and hearing their perspectives on things. It’s impossible to summon up inspiration, so whenever I feel it, I try to listen and make something. And it helps me to have several things going at the same time—each on its own time schedule, and each using a different part of the brain. So when I’m stuck on one of them, I can bounce over to a different one.

©Jason Fulford, Raising Frogs for $$$ and Notes on Raising Frogs for $$$

TM: Tell me about Photo No-Nos. Did you have some inspiration from Wrong by John Baldessari with this?

JF: I love Baldessari, but he was not a direct influence on this one. I was curious about things that photographers tell themselves not to shoot. Self-censorship, basically. So I interviewed over 200 photographers, plus a few curators and writers. We ended up with a list of over 1000 topics (organized alphabetically), and then each contributor wrote a short anecdote/memory about one of the topics. The results are really profound—funny, serious, thoughtful, practical, personal, absurd, all mixed together.

TM: What’s coming up on the radar for you, what’s next?

JF: I’m making my afternoon coffee right now. And after that, more pictures, reading, cooking, editing, teaching, listening, exercising, scanning, cleaning… another day on this mysterious planet.

Tristan Martinez (b. 1996 in Los Angeles, California) is an artist working in photography whose projects focus on the aesthetics of late stage capitalism while exploring themes of isolation, accessibility, and representation. Through digital manipulation and image sequencing, Tristan constructs ambiguous narratives that transcend individual identity and defy direct placement. Hyper focused on the banal aspects of daily life, his images challenge the viewer to make sense of what it is they are looking at and how that perception allows for meaning to form.

Tristan received a BFA in photography from The School of the Art institute of Chicago in 2020. Living and working in New York, Tristan is collected by The Joan Flasch Artists’ Book Collection and has shown internationally at Czong Institute for Contemporary Art and Nationally at The Latent Space Chicago.

Follow him on Instagram: @tristan_martinezz

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026