Memory is a Verb: Elizabeth Bailey: The House Next Door

Memory is a Verb: Exploring Time and Transience brings together twelve women photographic artists exploring the liminal space between time and transience. Represented in this body of work are the universal concepts of loss, mortality, and legacy, and the exploration of what inspires us to seek solace, and reexamine our histories; subsequently unearthing discoveries about ourselves, our relationships, and our place in the universe. This week and next we are sharing projects from the exhibition with interviews by the artists. Today we feature the work of Elizabeth Bailey who was interviewed by Rosalie Rosenthal. Baileys’s artist talk will take place on Thursday, March 17, 5 pm PST through the Los Angeles Center of Photography. Her project, The House Next Door is a narrative of neighborly voyeurism that ultimately results in a deep consideration of self.

Memory, often regarded as fixed or reflective of reality, in this project actively functions as a transformative shape-shifter. The ongoing tension between two seeming opposites – objective fact and subjective perception – together shape a cohesive whole, creating something larger and more nuanced than just the sum of its parts. As new insight illuminates the past, this influences our experience of the present moment; which is itself slipping into the past at the instant we seek to define or quantify it. In this manner, time is elusive, elastic, bending back and over itself; perception comes full circle.

The project Memory is a Verb: Exploring Time and Transience began as the world was besieged with fear and anxiety during a pandemic, longing for a return to normalcy. Feeling a sense of loss, we craved connection to our past and to each other. The pandemic also offered a unique moment in which to interpret things differently. Beyond nostalgia, which selectively employs memory as a self-soothing balm, our exploration reconsidered how we view the past, and what is of purpose and significance, in light of our changed circumstances.

Elizabeth Bailey is a Los Angeles based artist who uses photography to create evocative imagery that explores the themes of self, identity, memory, and longing.

Since the 1990s she has used staged scenes, portraiture and self-portraiture with implied narratives to consider what we conceal and reveal about ourselves, to others.

Born and raised in Minnesota, Bailey moved to Los Angeles at 18 to attend Occidental College. After receiving a BA in Philosophy, she went on to study photography and graphic design, finding that each informed the other. She currently works as a graphic designer and fine art photographer.

Her work has been exhibited in galleries nationally and internationally, including Light Box Gallery in Portland, Oregon; A Smith Gallery in Johnson City, Texas; and PH21 in Budapest, Hungary. Her photographs have been published in books and magazines including Float, Stubborn, and SHOTS Magazine, and are held in private collections.

Follow Elizabeth Bailey on Instagram: @elizabeth_bailey01

Follow Memory is a Verb on Instagram: @memory_is_a_verb

The House Next Door

When my reclusive, enigmatic neighbor of many years disappeared and died in her house, there were no friends or family to claim anything that remained: her body, her possessions, or even her memory. It seemed she was simply going to disappear.

Who had she been? What had happened to her? Convinced the answers lay inside her silent, vacant house, my curiosity grew into obsession.

“The House Next Door” documents the days and weeks and months that followed, as I gained entry and returned to the house again and again. Initially driven by emotional voyeurism – a subject/object investigation of a life outside of my own – this delineation began to blur over time. Were we really so different? Was I merely seeking to understand her, or also to escape into the house, as well?

A meditation on atypical beauty, perception, and point of view, “The House Next Door” ultimately considers how one individual, untold story can impact and alter the life of another. -Elizabeth Bailey

Rosalie Rosenthal: How did you come to photography? What led to the project that is featured today on Lenscratch?

Elizabeth Bailey: My father was a professor of English Literature and Film Studies, and an avid photographer. I grew up with literature, film and photography being emphasized as vital and vibrant forms of art; not just as creative expression, but as ways of exploring the world and the self. I studied Philosophy in college, and after graduation I began taking graphic design and darkroom photography classes at night. I discovered I loved staging, shooting and printing photos, and I created several bodies of photographic work (while working professionally as a graphic designer, which I still do.)

Rosalie Rosenthal: What led to the project that is featured today on Lenscratch?

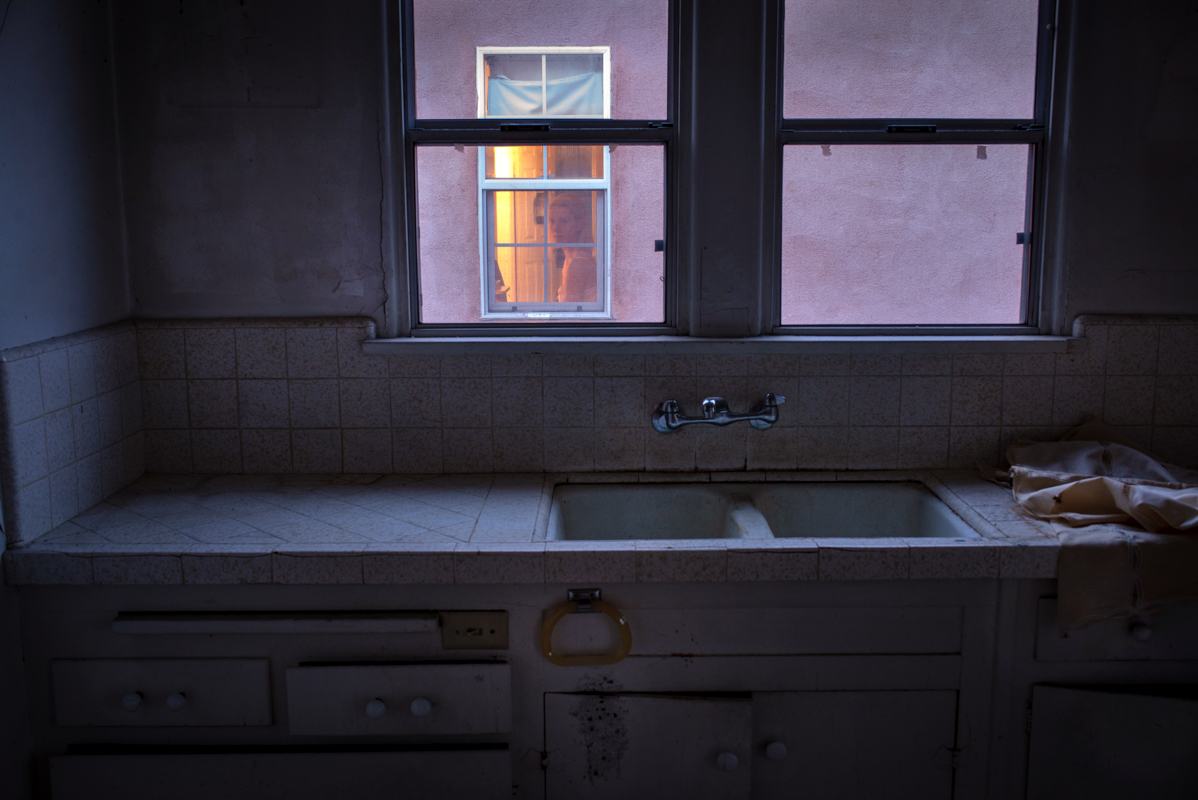

Elizabeth Bailey: My current project, The House Next Door, considers a theme that has fascinated me for years – what we choose to show to the world, the stories we tell (publicly) about ourselves, vs. what we hide away and conceal. I’ve always been intrigued by secret lives, by hidden stories, by what is left unsaid and undiscovered. In this case, I’d had the same neighbor for 17 years, an older woman who was somewhat reclusive. I knew her well – I thought. We were friends. We spoke often, every few days. Then suddenly, she disappeared. Her mail started piling up. I called the police to check on her, and I went in the house with them, where they found her body. I was stunned by how she had been living. The house was dusty and dirty, crammed full – a strange mix of beauty and decay, past and present. From the Coroner and Public Administrator’s office, I learned she had no family, no close friends. No one to claim her body or belongings. The house would go into probate and eventually be auctioned off. I looked across my driveway at her darkened, tightly shuttered windows, just 8 feet from my own. What had happened in her life? I grew obsessed with discovering who she really was and who she’d been, before every trace of her story vanished; before she disappeared completely. I was convinced the answers lay inside the house, and I needed to go back in there.

Rosalie Rosenthal: What drew you in? Why did you go into the house, that first time?

Elizabeth Bailey: I desperately wanted to go in, for many different reasons. Curiosity, and a need to verify what I’d seen, were big factors. The night I’d gone in with the police felt surreal. Had it really happened? I almost believed I’d dreamed it. My secondary reason was health and safety. The house was full of food, garbage and stacks of paper. A month had passed, and nobody was coming to do anything about it. I donned protective gear and went in. I cleared out the obvious trash and food. I started tending the overgrown garden, front and back. She had loved her garden, and this felt like a way to honor her. I was not making photos yet, just caring for the house, and spending time looking at the contents. I unearthed shoeboxes of letters, old photos, things she had written. I pored over it all. I read about her thoughts, beliefs and ideals. I was starting to actually know her. She was no longer going to disappear.

Rosalie Rosenthal: How did the act of photographing contribute to your experience? Or why was it important to photograph rather than just look and experience the space?

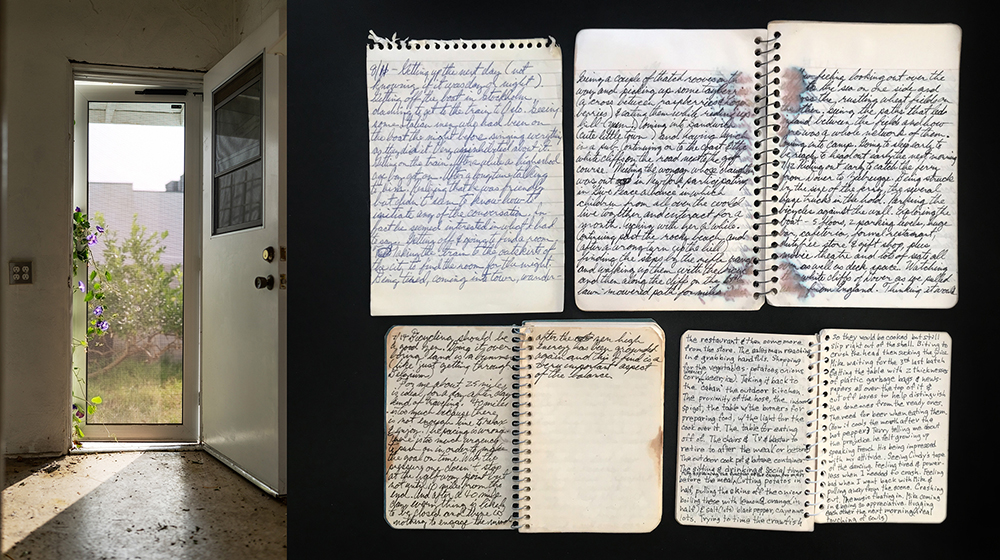

Elizabeth Bailey: Months went by, where I cared for the house and investigated her history, but I made very few photos. Then one day, early in the morning, a cleanout crew drove up with a dumpster. Trucks followed. For the next 2 days they methodically unloaded every valuable from the house, tagging furniture and rugs and vases and boxes and china, hauling them away in the trucks. Everything else – her personal items of no value – were tossed into the dumpster. Although I knew this day would come, I was unprepared for my emotional response. I was near panic as I watched helplessly. I had grown attached to her story, to the house, and to feeling as though I were a caretaker of her history and her things. The reality came crashing down. My proximity had felt like privilege, but it wasn’t. What was I? An interloper? A benevolent meddler? I was a photographer. A storyteller. That night I climbed into the dumpster, and retrieved everything I could.

With the crew gone, I went back into the now-empty house, bringing with me the items I’d salvaged. A psychological shift had occurred, and the ephemeral nature of this experience was laid bare. It could end at any moment. At this point I began making photos, documenting everything. The house, the objects, the play of light on the walls, the dusty lace curtains, the patina of dirt, and finally myself – in the house, having this experience.

Rosalie Rosenthal: How was your self-conception and your understanding of your neighbor altered by your experience? Were they intertwined?

Elizabeth Bailey: I began this project thinking that my neighbor was so different from me, that I was nothing like her. And I came to see that wasn’t so, I came to feel a tremendous amount of empathy for who she was, and the coping skills she employed. It dawned on me one day, as I crept into the house, that I was (and had been) using the house next door as a distraction, a diversion away from things I wanted to avoid. I was starting to neglect certain parts of my life, because disappearing into the house next door felt so engrossing. Being there took me outside of myself, away from my own life. I was using it as a way to escape from ordinary reality. I was not so different from her. We both escaped into that house.

Rosalie Rosenthal: Can you talk about making your photographs? Did you have any challenges or difficult decisions to make? To what extent, if any, were you embodying your neighbor, or were you capturing your emotional response in the environment?

Elizabeth Bailey: As I got further into the project, I started bringing objects into the house – I found artwork and curtains and things I thought she might have liked. I began posing for self-portraits in character as her, not as me. I considered how she might have felt (back when she was living next door) and what her life was like. I also reflected on the fact of my own undeniable emotional voyeurism as a driving force in this story. What was behind it? This project ultimately made me evaluate myself and my own motivations, too.

Rosalie Rosenthal: This project unfolded because of your neighbor’s untimely death. Obviously, her life is integral to your story, but she is without agency in its unfolding. Can you talk about the issue of her privacy?

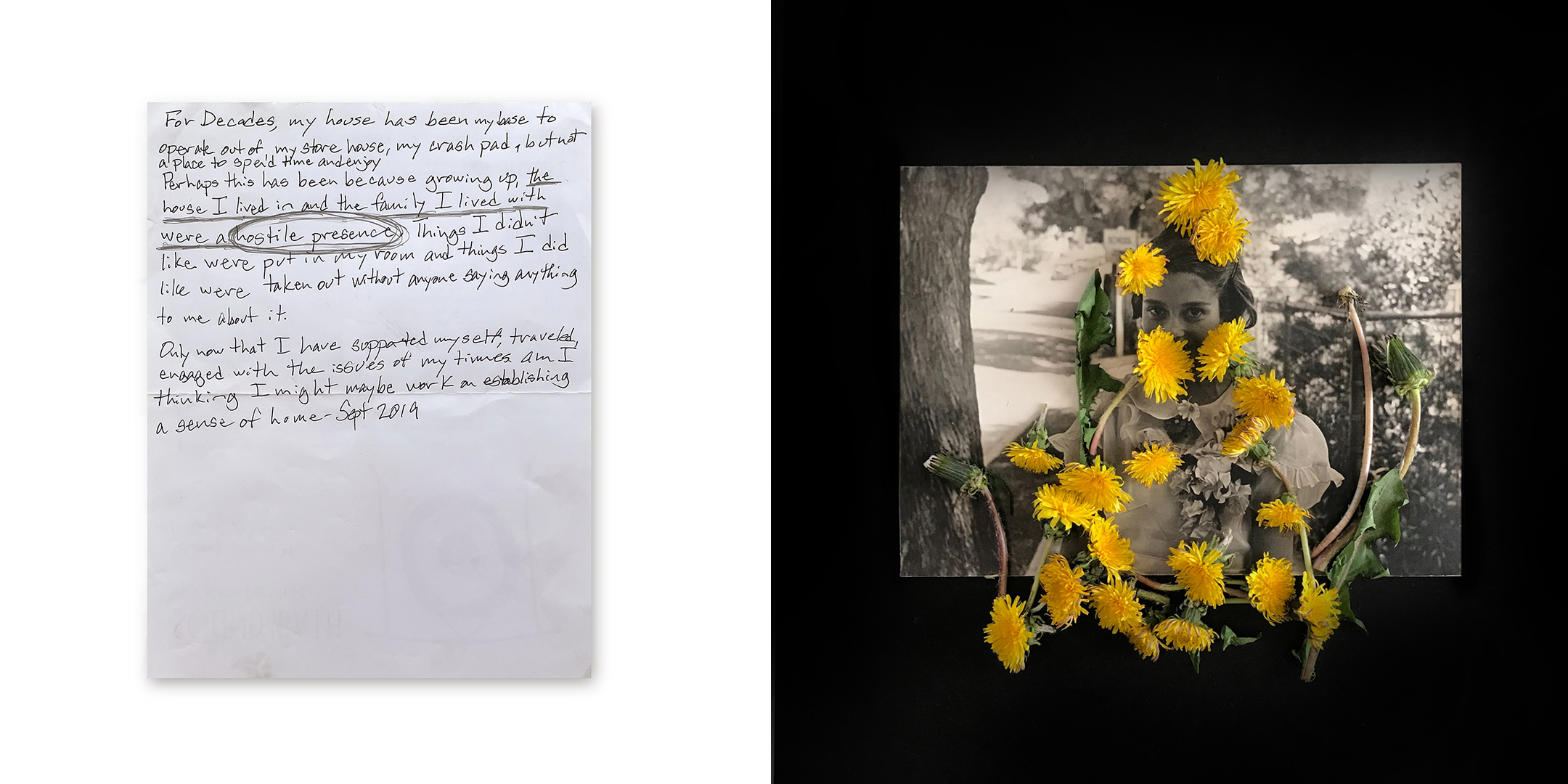

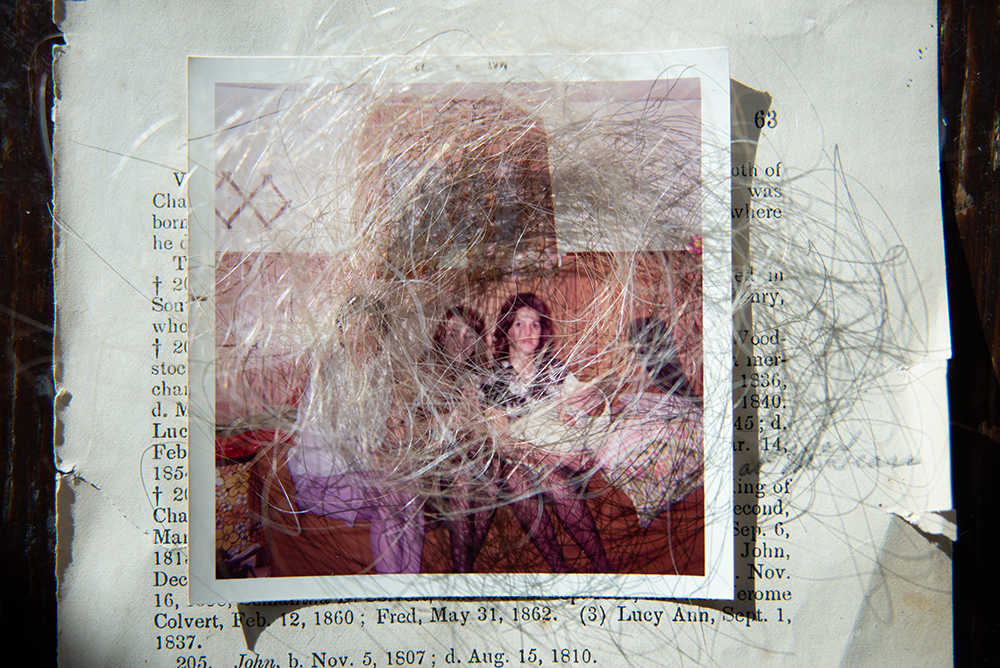

Elizabeth Bailey: I’ve considered this many times. There are a couple of issues. One, would she have consented? And two, am I upsetting family or revealing who she is? Well, she has no living immediate family members, and I’m not using her name or any (unmanipulated) images of how she looked in her adult years. From her writings, I can tell you she was a very unconventional person, with her own theories about art and culture. She was a huge fan of upsetting norms, of challenging the status quo in many ways. I like to believe she’d approve of my work, since it comes from a place of respect for her and her story. There are things about her I am not showing or saying, things I’m holding back. And some of what I do show – tattered curtains, the patina of dirt and grime in her house, handwritten notes – I’m presenting them because I actually find them compelling and beautiful, in the complex blend of strength and human frailty that they reveal. They tell me she was a survivor, and she compartmentalized certain things to move forward. She created a meaningful life by doing that. I respect that, and I respect who she was.

Rosalie Rosenthal: In some cases, you have manipulated photos or ephemera that you salvaged from the house, or paired them with photos of your own. What was your intention in doing this?

Elizabeth Bailey: As I learned more and more about my neighbor’s life history, I wanted to include my interpretation of her perspective in the presentation of her ephemera. For example, I learned that she had completely cut herself off from her family – and some of the reasons why. The family photos I show reflect the hurt and anger she felt; by erasing parts of their faces, by obscuring certain details, by highlighting things that indicate how she felt. As I did this, I thought a lot about history and personhood. Am I getting her history completely right? No, because I am presenting it from my perspective, which is one of limited knowledge. However, is there any history, anywhere, that is recorded or presented free from a perspective? To report on something means to imprint the reporter’s subjectivity upon it, whether intentionally or unintentionally. Mine was intentional.

Rosalie Rosenthal: What are your plans for this body of work?

Elizabeth Bailey: I’m honored to have several images from this series in group shows in various galleries right now.

But ultimately, I envision The House Next Door as a book, and I’m currently in the process of putting it together. I hope to publish or self-publish it this year, if possible. This will be my first photo book, and I’m very excited.

Rosalie Rosenthal: I’d love to hear about other projects that you’ve worked on. Has there been any thematic overlap?

Elizabeth Bailey: Yes. Prior to The House Next Door, I created a series titled “The Woods,” in which I recreated scenes from my childhood, exploring and revisiting how as a child I retreated into a fantasy world – a wooded area near my home – as an escape from uncomfortable realities I experienced growing up. Both projects incorporate a certain fluidity between fantasy and reality, and a reimagining of the self and environment as a means of coping. I also have an ongoing body of work “In Flux” which is self-portraiture taken over the course of years, capturing the emotions surrounding various transitions in my life. I guess I’ve always seen photography as ideal for capturing emotional flux and volatility, for presenting imagery where ambiguity invites the viewer to wonder, to impose their own perspective upon what they are seeing, even as it seems to tell a story. Fact and fantasy blurred together. That’s what I love to create.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026