Earth Week: Elizabeth Ellenwood: Fading Reefs Collection

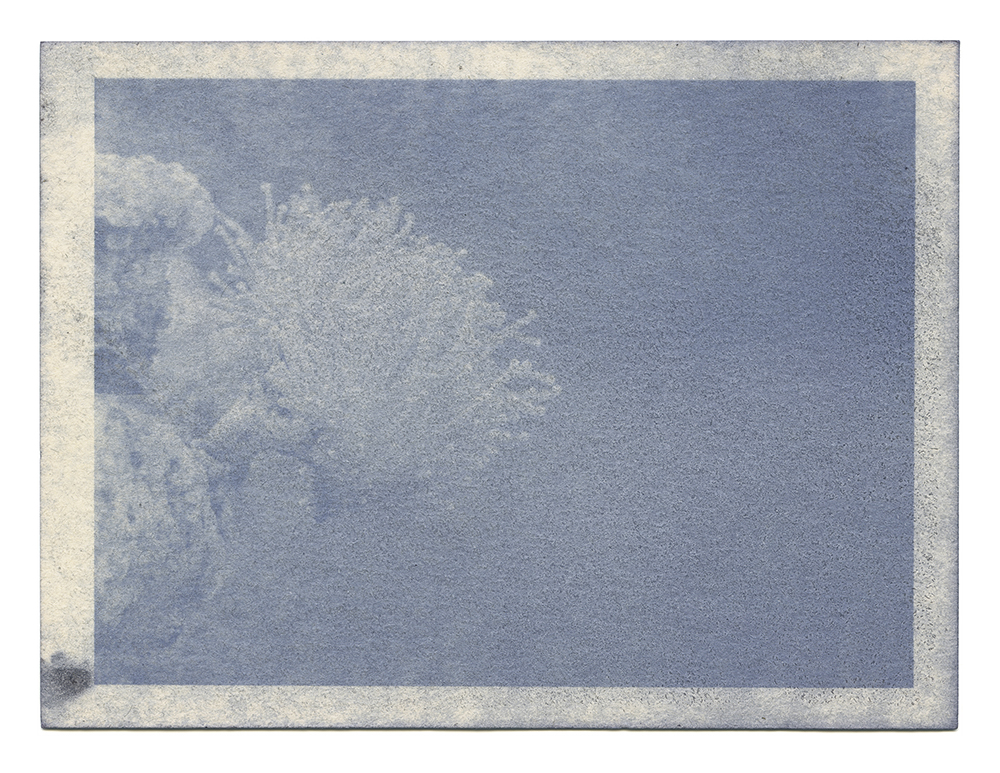

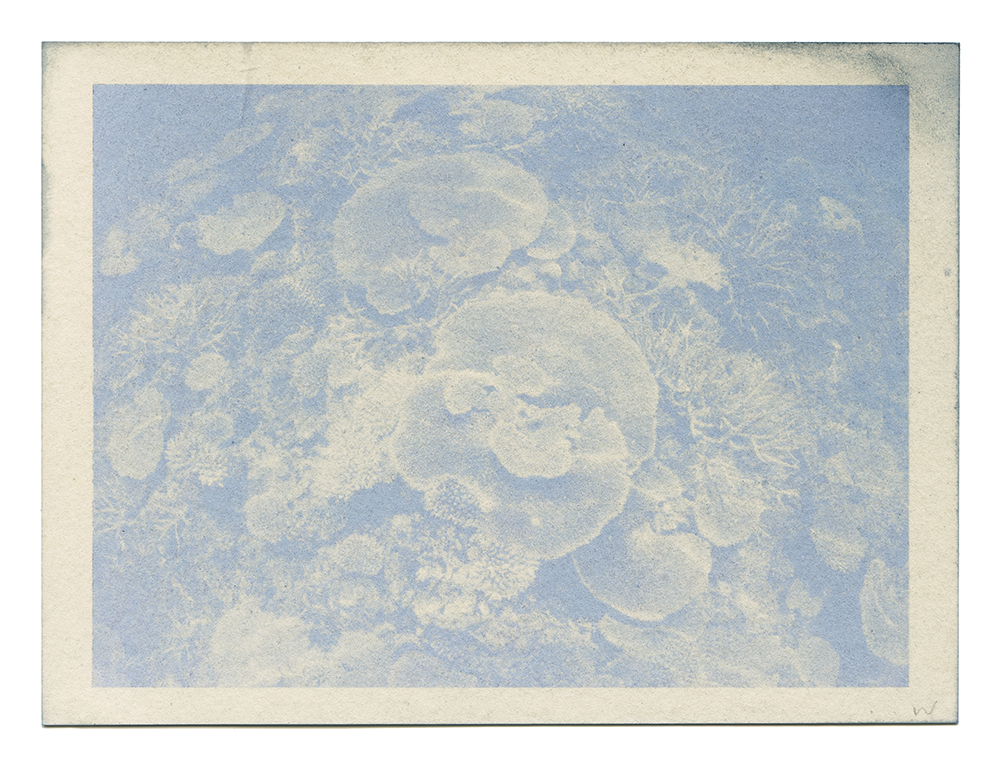

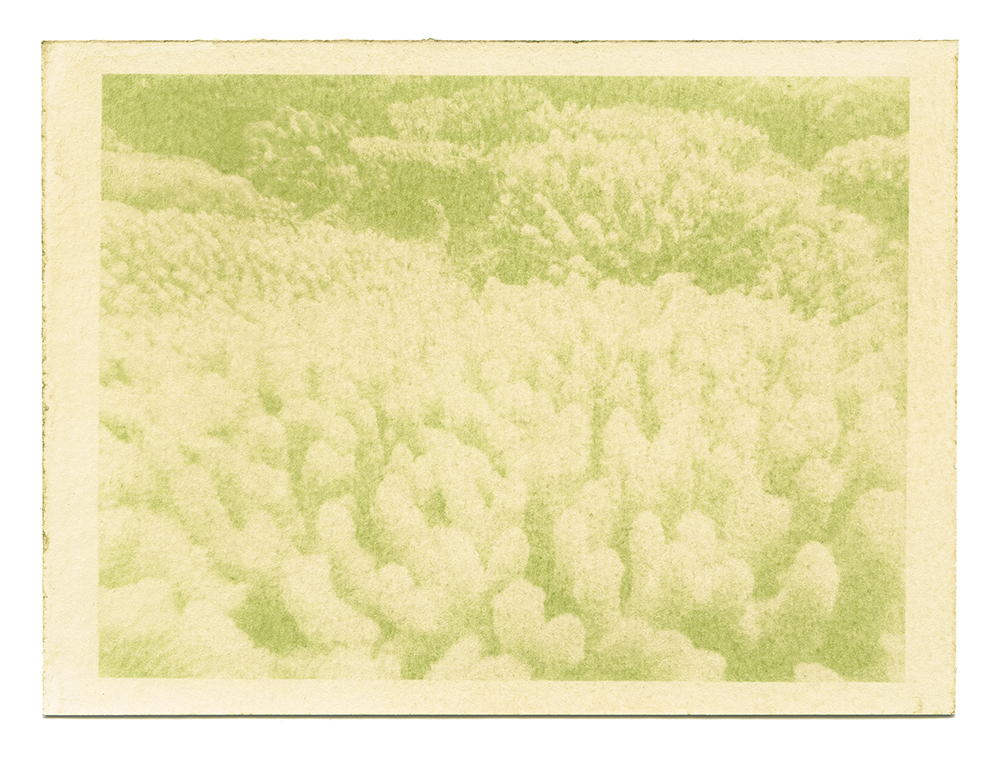

©Elizabeth Ellenwood, Fading Reefs Collection, Anthotype, RedCabbage, 4.5x6inches (paper size), 21.5hours, 2019-2021

This week we focus on bodies of work are linked by this thematic lens: making the often-invisible nature of the global climate and the ecological crisis more visible using conceptual, lens-based art techniques. Each body of work speaks to a different aspect of the climate and ecological crisis: sea level rise; coral bleaching; habitat loss and environmental destruction; deforestation; melting glaciers; plastic pollution.

Elizabeth Ellenwood is a photographer and diver whose work combines historical photographic techniques with the most pressing contemporary issues of environmentalism. Fading Reefs documents global warming’s impact on coral reefs via anthotypes. In this early photographic process, paper is infused with plant-based pigments. Sunlight bleaches the exposed areas, thereby creating an image of whatever light-permeable object has been placed on it during exposure. In this case, Ellenwood uses photographic negatives of coral reefs that are themselves being bleached by a long and slow process. Because any exposure to light causes these unfixed images to fade, for Lands End they are shrouded in black velvet—a nod to the traditional mode of Victorian era exhibition. Fading Reefs is more than a technical demonstration, however: it is meant to be experienced as a consciousness-raising memorial for the lost environments of climate change. (from For-Site Fellowship)

Video by Eighty Six Media

Elizabeth Ellenwood is an artist, photographer, and ocean farmhand living in Pawcatuck, CT. Her work revolves around the ocean and making images that call attention to pollution in our waterways. Elizabeth is currently in Norway as a U.S. Fulbright Research Scholar and an American Scandinavian Foundation Fellow. She received a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Photography from The New Hampshire Institute of Art and a Master of Fine Arts in Studio Art from the University of Connecticut.

Follow Elizabeth Ellenwood on Instagram: @among_the_tides

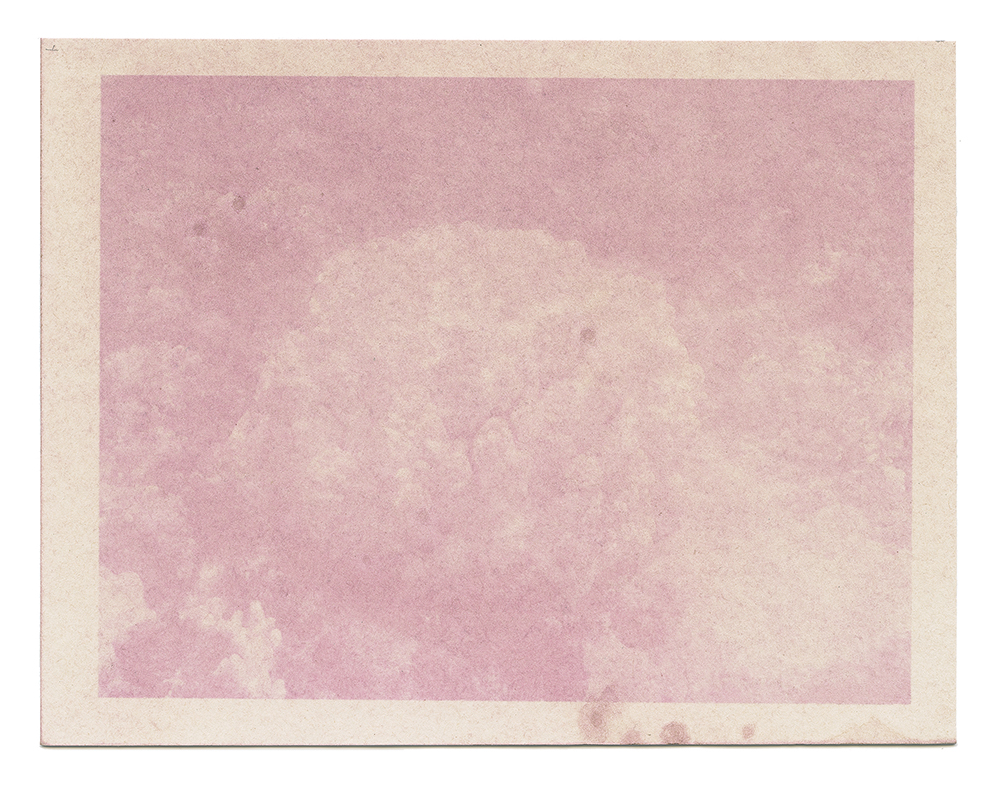

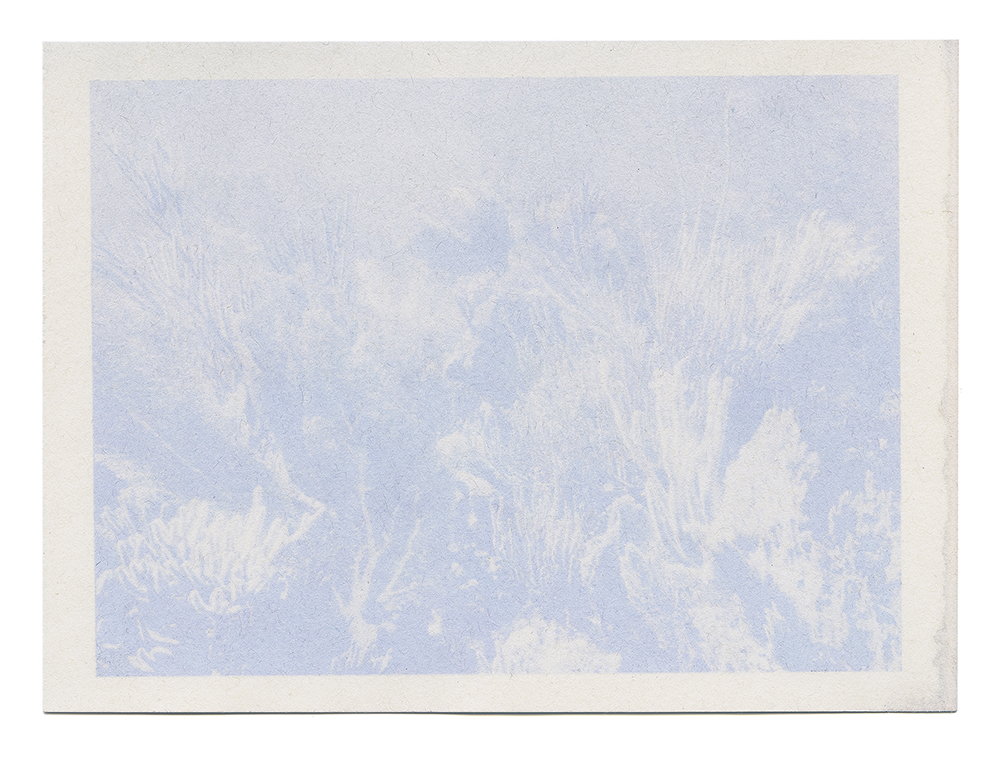

©Elizabeth Ellenwood, Fading Reefs Collection, Anthotype, RedCabbage, 4.5x6inches (paper size), 66.25hours, 2019-2021

Fading Reefs

Our ocean’s coral reefs are rapidly turning into anemic wastelands due to global warming. Fading Reefs aims to visually communicate coral bleaching through the photographic process of anthotype printing, which uses the light sensitivity of plants to create a photograph. The print develops as the sunlight destroys the pigment in the exposed areas of the plant emulsion, bleaching the print. Unable to be fixed, the prints will fade over time. The anthotype process is a perfect way to tell the reefs’ stories, the bleaching pigment in the prints references the devastating loss of pigment rich algae that not only give corals their colors, but most importantly keep them alive. The anthotype prints in Fading Reefs are delicate, time sensitive, and beautiful – just like our ocean’s coral reefs.

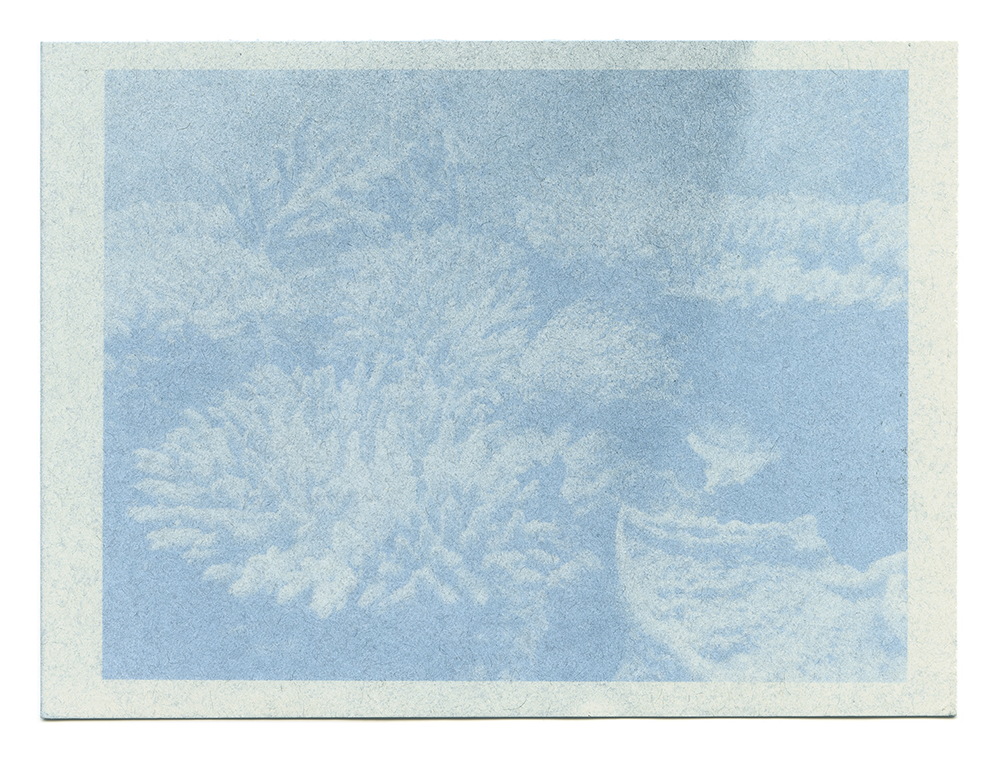

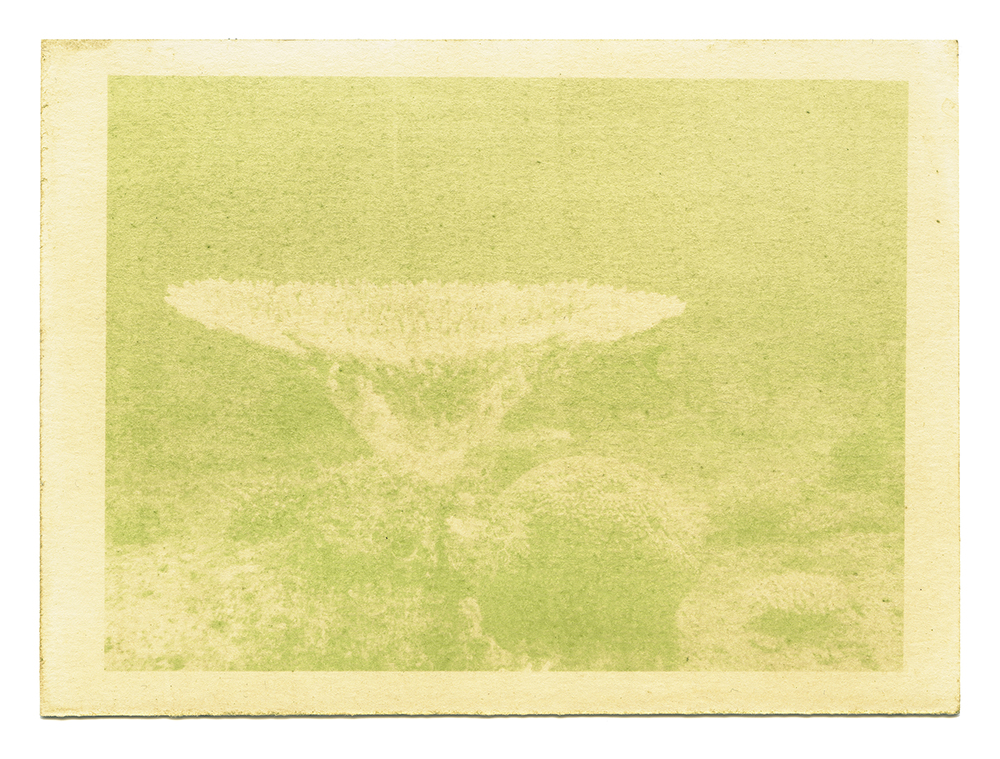

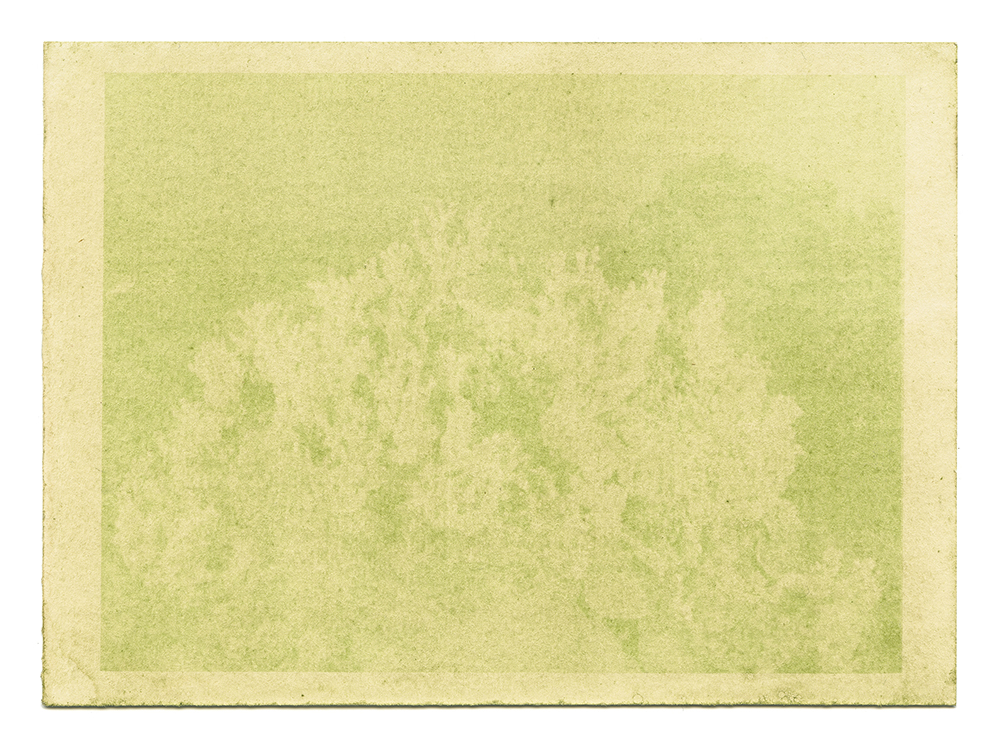

©Elizabeth Ellenwood, Fading Reefs Collection, Anthotype, RedCabbage, 4.5x6inches (paper size), 33.25hours, 2019-2021

Climate change means ocean change. The ocean’s temperature is warming, it is becoming more acidic, sea level is rising, and storm patterns and precipitation are changing. All of these factors individually create stress for corals. Combined, they have demolished the reef systems that have flourished for centuries. The coral reefs of my childhood memories are bleaching, and entire ocean ecosystems are vanishing due to the loss of their habitats.

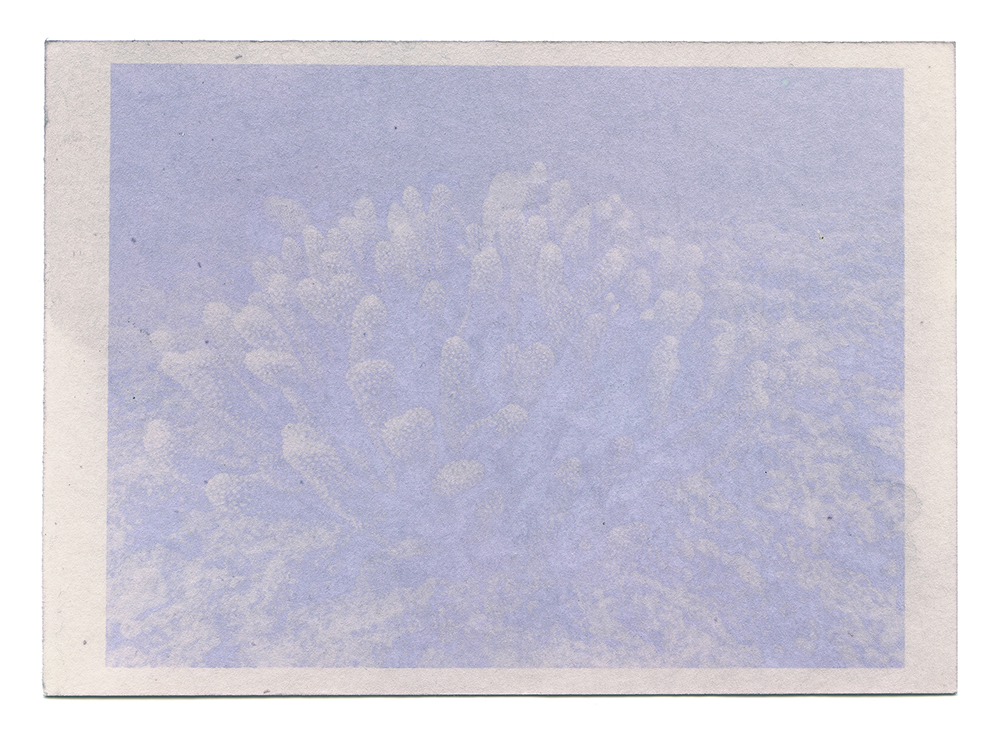

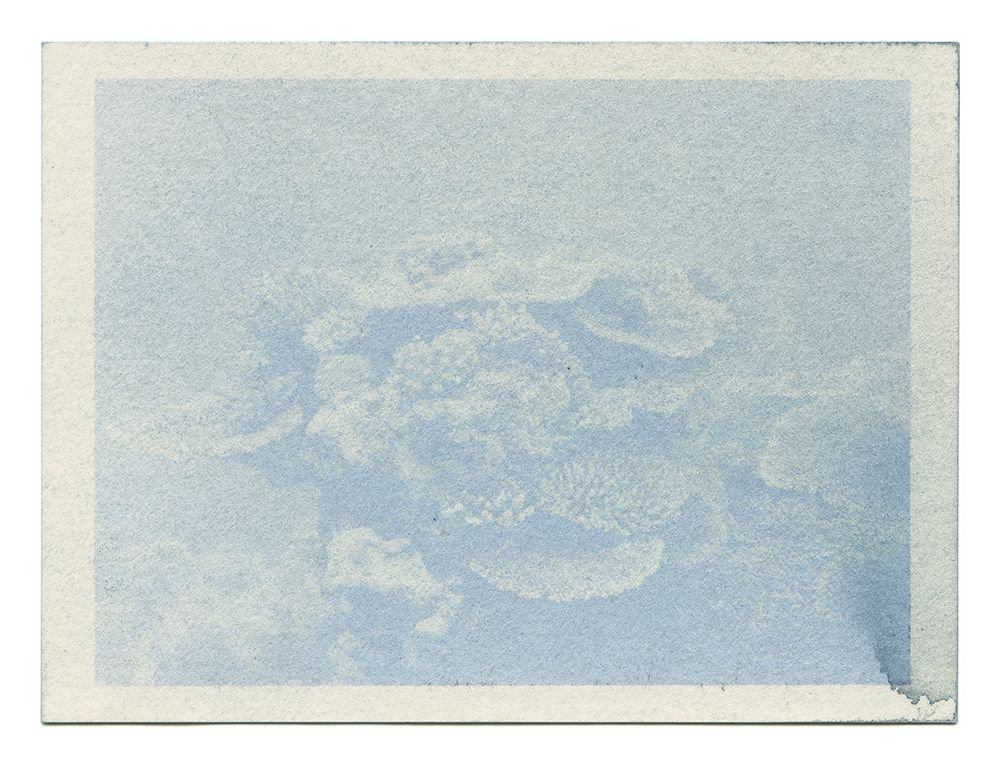

©Elizabeth Ellenwood, Fading Reefs Collection, Anthotype, RedCabbage, 4.5x6inches (paper size), 23.25 hours, 2019-2021

The term “coral bleaching” has bounced around news headlines for years, but it took documentaries like Chasing Coral and Mission Blue to inspire me to dig deeper into the science. Corals get their colors from pigment-rich algae that live within their tissues. The coral-algae partnership is symbiotic, each supporting one another. When stressed from the ocean changes, the algae are expelled from the coral, revealing the white coral skeleton underneath. This bleaching triggers a domino effect: all living organisms that relied on the reef habitat either vacate or die, from the smallest plankton to the largest predator. The reef system is rapidly turning into a wasteland; no corals, no fish. This devastation is taking place on a massive scale and at a rapid rate, with nearly half of the world’s coral reefs bleached or severely damaged.

©Elizabeth Ellenwood, Fading Reefs Collection, Anthotype, Red Cabbage, 4.5x6inches (paper size), 21.25hours, 2019-2021

This devastation has swept through coral reefs in the Bahama — the very ones that brought me so much childhood joy. I feel a loss for the diverse ecosystems that depended on the corals. Caught in a vortex of pollution, rising temperatures, acidification, and overfishing, thinking about humanity’s destruction of our waterways can be paralyzing. But to improve our relationship with the ocean and bring about positive change, we must fully understand the effects of our actions.

My research on coral reef bleaching led to the creation of my series, Fading Reefs. I am inspired by the biology of corals, driven by sadness for the loss of the reefs from my childhood, and compelled to shed light on this destructive cycle. It is important to me to create based on science and in a sustainable way, using environmentally friendly processes and as few materials as possible. One of the oldest photographic processes, the anthotype, uses the light sensitivity of plants and sunlight to create an image. Because these prints fade over time, it is difficult to research historical images, though documents and research track its emergence from 1816 to 1844.

©Elizabeth Ellenwood, Fading Reefs Collection, Anthotype, Red Cabbage, 4.5x6inches (paper size), 20 hours, 2019-2021

I see the process of coral bleaching and the anthotype process as linked together. Making anthotypes requires time and patience. This process begins with crushing or juicing a plant to create the light-sensitive emulsion. A piece of paper is then soaked in the liquid and dried, absorbing the pigment of the plant. An image on transparency film is placed on top of the color-stained paper and then placed in direct sunlight. The image develops and appears on the page as the sunlight bleaches the pigment in the exposed areas of the plant emulsion. This is a very slow process; depending on the plant used and the strength of the sun, the printing can take days, weeks, or even months. Once developed, anthotype images will fade over time, especially if they are exposed to UV light. There is no way to make them permanent, which I see as a beautiful quality to embrace.

In the 1800s, anthotypes were stored in what they called “night albums” and only viewed by candlelight to help preserve the images. Some artists build boxes or use black fabric over their framed piece to protect the prints while they are on display. When Fading Reefs is exhibited, I embrace the impermanence of the process and leave my prints uncovered to speak to the vulnerability of the corals. The anthotype process is a perfect way to tell the reefs’ stories, the bleaching pigment in the prints refers to the devastating loss of pigment-rich algae that not only give corals their colors, but most importantly keep them alive. The prints in Fading Reefs are delicate, time sensitive, and beautiful — just like our ocean’s coral reefs. – Elizabeth Ellenwood

©Elizabeth Ellenwood, Fading Reefs Collection, Anthotype, RedCabbage, 4.5x6inches (paper size), 17 hours, 2019-2021

©Elizabeth Ellenwood, Fading Reefs Collection, Anthotype, Kale, 4.5x6inches (paper size), 6.5 hours, 2019-2021

©Elizabeth Ellenwood, Fading Reefs Collection, Anthotype, Kale, 4.5x6inches (paper size), 9 hours, 2019-2021

©Elizabeth Ellenwood, Fading Reefs Collection, Anthotype, Kale, 4.5x6inches (paper size), 1.5 hours, 2019-2021

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025

-

Lauri Gaffin: Moving Still: A Cinematic Life Frame-by-FrameDecember 4th, 2025

-

Dani Tranchesi: Ordinary MiraclesNovember 30th, 2025

-

Art of Documentary Photography: Elliot RossOctober 30th, 2025

-

The Art of Documentary Photography: Carol GuzyOctober 29th, 2025