The Dynamics of Photography and Disability: Camilla Jerome: Wounds Need Air

©Camilla Jerome, Untitled, Double Exposure, 2020, Archival Pigment Print Image description: A horizontal black and white landscape photograph of a lake with a double expo-sure of the same scene slightly off-set vertically. There is a dense treeline in the background, and five rocks of various sizes protruding from the water. One rock on the left side falls out of the frame, three smaller rocks are in the middle of the photograph, and the largest rock is the farthest away and on the right side of the frame. In front of the largest rock, a swan is swimming in the lake facing the right side of the frame.

This week we are looking at projects by disabled/chronically ill photographers. The definition of dynamics is “forces or properties which stimulate growth, development, or change within a system or process.” Each of these artists is approaching their work in ways that embrace this meaning, enacting change and raising important questions about societal systems through their ideas, craft, and processes they use.

Camilla Jerome (she/her) is an interdisciplinary artist from Massachusetts. She holds an MFA from Rhode Island School of Design and a BFA from Lesley Art and Design. Her photographic work interprets disability as a fluid state, chronic illness visualization, and embodied knowledge as testimony.

Jerome is a 2021 Critical Mass finalist and made the LENSCRATCH 2021 Top 26 to Watch List for her project Wounds Need Air. She has recently exhibited work at Sol Koffler Gallery, Umbrella Arts Gallery, Gallery Kayafas, The Faye Chandler Emerging Artist Exhibition at Boston City Hall, 10th Annual Julia Margaret Cameron Exhibition for Women Photographers in Barcelona, Laconia Gallery, and The Boston Architectural Society. She was named one of Flash Forward’s 2018 Top 100 Emerging Photogra-phers and was selected to participate in CENTER’S 2018 Santa Fe Portfolio Reviews. Jerome has received awards from the 10th Annual Julia Margaret Cameron Fine Art Photography Series and Personal Photography Series Winner, PDN’s FACES Portrait Competition Professional Personal Work Winner, and Lesley University Award For Ex-cellence in Photography. She has been published by Flash Forward, Recently (self-published), PDN, Ain’t Bad, Mull it Over, American Chordata, C-41, and LENSCRATCH.

Wounds Need Air

It wasn’t just one accident or disease but a series of disorders that went undiagnosed and untreated. My chronically ill and disabled body is not in a fixed state but a fluid mode of being fueled by deeply embodied knowledge. Today, doctors’ bedside rheto-ric is filled with modern terms for hysteria to gaslight and inflict gendered medical abuse. This form of medical trauma is endemic amongst millions of women globally. The disbelief of our suffering is drowned out by the western ideals of whiteness, beauty, femininity, and health.

After fifteen years, I have been diagnosed with endometriosis and hypermobile Ehler’s Danlos Syndrome. Unfortunately, medical diagnostic imaging cannot show these complex connective tissue disorders, and for a time, I felt as though photography had failed me. Whether I’m using a DSLR, a medium-format rangefinder, polaroid, cyanotype, or an iPhone, these different tools create multiple access points of deciphering and discernment. Images crafted from digital and analog, color and black and white, photographic processes are a gesture of reclamation of my voice and lost time. The joy that comes from my artistic practice is a counterbalance to the endurance of chronic illness. I cannot heal without answers, but maybe healing is the gentle embrace of it all – myself, my life, and the ground beneath my feet, rising to meet me as I walk through all of my moments.

Megan Bent: Welcome Camilla. To start, can you please tell us a bit about yourself?

Camilla Jerome: I live in Massachusetts and have been here since I was 6. I’ve lived in 12 different cities in and around Boston but grew up north of the city. I currently live in a very small town called Nahant that is connected to the mainland by a causeway. It’s technically a little island so I’m surrounded by water, that’s been influencing me and my work.

My partner, Josh, is from Salem and we grew up in neighboring towns. We met at a bar on Halloween, his band was covering The Beatles, I had just finished photographing a wedding and I was wearing a badass pantsuit. We chatted and later I asked a mutual friend for his number. I texted him and asked him out on a date. Now we have a cat named Linda McCatney, and our dog is Yoko Ono, some of my favorite artists who are also the women behind The Beatles.

MB: How long have you lived in Nahant?

CJ: We’ve been here for about a year. We were looking to move as Josh was commuting to Salem every day, and was stuck in traffic all the time. Originally, we thought that the listing was a scam or fake. But it was totally real, and we just jumped on it, and we moved last February right in the dead of winter which sounds terrible but I’ve really grown to love the beach and the ocean in the winter. No one else is there, you’re just completely alone. I have this entire place to myself and it’s just like I love that. It’s been very therapeutic.

©Camilla Jerome Untitled, Foot, 2020, Archival Pigment Print Image description: A black and white, horizontal and abstract photograph of the sky with clouds. Fall-ing off the right side of the frame is the underside of a leg and foot that runs the length of the image.

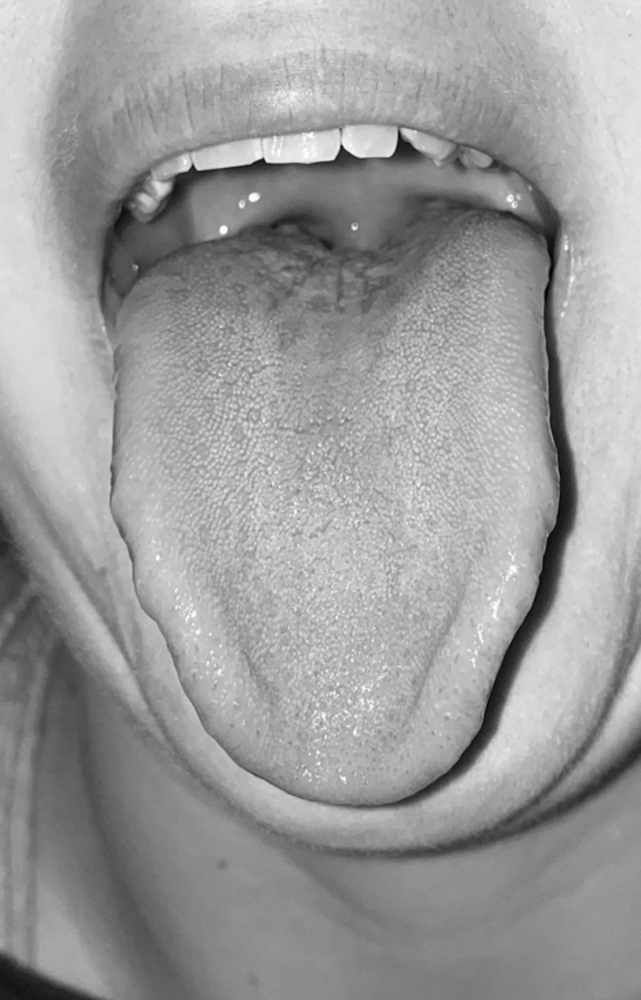

©Camilla Jerome, Untitled, Tongue, 2021, Archival Pigment Print Image description: A tightly cropped black and white vertical photograph of a mouth and a tongue sticking out. The lips and top teeth are at the top of the frame.

MB: What does disability/chronic illness mean to you personally, and what does it mean in regards to your work or your photography?

CJ: There’s very little divide between the personal and my art. I kind of fell into photography at the same time my symptoms started to become chronic. I was 15, sophomore year of high school and it started with intense chronic pain in my chest, and slowly became widespread. Doctor’s just couldn’t figure out what was going on or what was causing it. So I went from being a two-season varsity athlete, as a freshman to not being able to play sports at all. And so I fell in love with photography. I took a photo course, and I became obsessed with the camera and light. My artistic practice has developed alongside my illnesses and disabilities. They really go hand in hand. If I’m not making work it’s a sign that I’m not in a very good place. It’s just something I need to keep doing.

A lot of my work is very performative, and in some regards it’s a very photojournalistic documentary style. I blend all the different styles that I have studied over time. But I like to take my work and the performance aspect a little step further, and I think of it as a self-revelatory practice.It’s equal parts therapeutic and aesthetic, where neither one is sacrificed, but actually amplify each other.

My newer work, the work that I made during grad school at RISD takes on a certain level of risk, and it’s very current. So while yes my work is autobiographical, I’m not just thinking about what happened in the past, but rather what is happening to me right now. I process things visually that I don’t necessarily have a verbal language for. My work is across the board really intuitive.

I work based off of my energy. I’m sure you can understand, in terms of having chronic fatigue and then random bursts of energy. I really tried to honor that in grad school because it was really difficult for me as a chronically ill and disabled person. RISD is a very ableist campus, it’s really spread out and College Hill is one of the steepest hills I have ever casually encountered. I took my phone and used the level and it was like almost a 30 degree incline. It wasn’t until the pandemic that I realized how far I was pushing myself and pushing myself too far. I was running on fumes and then at the start of my final semester, I was bed bound. I was in bed going to class on zoom. I had to tap into the part of my intuition and rely on the fact that I knew what I was doing, I knew what the work was saying, even though it wasn’t all there for me consciously. I couldn’t put everything together in my head but somehow, it made sense on paper, and I kind of just went with it.

©Camilla Jerome, Untitled, White Flowers, 2020, Archival Pigment Print Image description: A black and white vertical photograph of a white outdoor PVC curtain at the cen-ter of the frame. The curtain is in the sun, falling from left to right and the curtain is gathered and sinched at the top third. The background of the image is dark and in shadow. Directly behind the cur-tain are several white flowers peeking out from either side. The flowers are suspended off the ground. In the foreground of the photograph, there is a black translucent screen that begins at the very bottom of the frame and extends through the top of the image.

©Camilla Jerome, Untitled, Eye, 2019, Archival Pigment Print Image description: A color vertical photograph of a white person’s left eye and eyebrow. Three fin-gers come up from the bottom of the frame and are pulling at the lower eyelid to expose bright pink skin and redness of the eyeball. The iris is looking up and to the left and barely showing.

MB: So in your project Wounds Need Air I see an oscillation or blurring between nature and the body. For example there are some images where marks on the body resemble patterns and nature. Can you say more about that? And what if anything, that means in your practice?

CJ: Yeah, it definitely is. I see so much of myself reflected in nature and that relationship is ever changing. I find solitude in nature, and I find myself craving to go swimming, the weightlessness of water and the ability to float.

The feeling of being anchored to the depths of the earth is a way that I think of the fatigue that comes along with my diseases. It’s just this immense gravitational force that pulls you horizontally, and you just can’t resist it.

I grew up like in the woods, in a barn, and around animals and I always felt at home when I’m in nature and perhaps one of the only places I feel where I belong. I’ve always been drawn to themes of water and fluidity within my work. Wounds Need Air, came from releasing myself from strict boundaries of image making. I would really focus on using a specific camera per project or you know, working strictly in film or digital or like if am I not if I’m not shooting film, am I really an artist?

I just started using whatever I had, and whatever I felt like bringing with me whatever I liked or called to me at that time. The work is made with an iPhone, polaroid, Fuji 6×9, Canon Mark III, or large format pinhole images all came together and ended up as a book.

MB: For me when I look at the images they’re beautifully stunning. But there’s also this kind of quiet poetics to individual images, but also different dyptics or triptychs that you can pull together as you’re moving through the work.

CJ: Yeah, Thanks.

©Camilla Jerome, I Tried So Hard To Keep It All Together (Walking Study on Mud), 2020, Cyanotype and bathwater on canvas, unraveled by hand, mirror, wood, and monofilament 34” x 84” x 96”. Installation View, Image description: A raw canvas is suspended in front of white walls. The canvas has varying densities and saturations of blue cyanotype with undyed portions of the canvas. It hangs from a white frame. Below the canvas is a large mirror sitting on a white platform. One piece of the canvas hangs down to touch the mirror. At the top of the frame, there are blue and white opaque pieces of fabric to create a sky-like appearance.

©Camilla Jerome, I Tried So Hard To Keep It All Together (Walking Study on Mud), 2020, Cyanotype and bathwater on canvas, unraveled by hand, mirror, wood, and monofilament 34” x 84” x 96”. : Installation View, Canvas Detail, Image description: A up-close image of the canvas with a white background. The edges of the canvas are uneven, frayed, and unraveled. The canvas creates a point at the top of the photograph’s frame and comes towards the camera falling out of focus. There are varying densities and saturations of blue cyanotype along with an undyed raw canvas

MB: I wanted to learn more about your master’s thesis work, I Tried So Hard To Keep It All Together. I saw that it was created with bath water, and so that made me curious and wanting to know more about bathwater as a conduit for creating the piece. And then just some more information about the decisions you made. It looks like a cyanotype that has been ripped but reassembled, and there’s a mirror underneath. And yeah, I just wanted to hear some more about those details.

CJ: About halfway through my degree I was doing walking studies while I was taking an installation course where we had to measure our installation site in a non-formal non-traditional sense, like not using tape measures, or things along those lines. One of the things that happened while making work during the pandemic was, I had to use what I had lying around. My bathroom became my studio, and my bathtub was where I made most of it. During the day I was making work in that bathtub and then at night I would be taking a bath trying to find relief. But I loved the fact that I was making work in this same vessel where I would also go to heal.

So, I started collecting my bathwater and then, hopefully, the idea was that bits of me would then be in the emulsion. I was mixing cyanotype with my bathwater. I had raw canvas and ripped up pieces that were 72 inches long by 30 inches wide, which are kind of the approximate dimensions of my body. And then dipping my feet into a foot bath of cyanotype solution I would walk for 15 min back and forth on the canvas.

I don’t really recommend it to anyone, I don’t think that’s what you’re supposed to do with cyanotype. Again, there’s that level of risk taking. I was thinking about all the different chemicals I’ve put in my body like medications, radiation from imaging, injections, etc. So I was kind of like ‘Whatever, I’m just gonna dip my feet in cyanotype.’ I did (walking studies) in grass, cement and mud. Mud is the one that you see in the final installation. It worked differently because it was a wet surface and the cyanotype was able to penetrate the canvas and go onto both sides. And so I made sure to expose both sides. so it’s a you know completely dynamic piece.

Then I started unraveling it by hand and just pulling the threads. It, and that’s kind of how I feel about pushing to get seen in medical care when your symptoms get to be too much and I really need to push to get this taken seriously, you know? To the point where symptoms become unmanageable. I thought about it as pulling the thread, and I’m watching everything unravel. But really I’m the one doing it, I am facilitating my own unraveling.

Especially in the video performance piece (Show Me Where it Hurts) and with this canvas there is kind of a masochistic element to it. Pushing yourself to the limits knowing that maybe it’s too much for your body. Or that, deep embodied knowing that it’s too much. But you continue to push through it, maybe it’s a subconscious thing, or maybe it is conscious, but I’m pretty sure I knew what I was doing so maybe it’s a little bit of both. It took me somewhere like close to 30 hours to unravel. The title makes it seem that the canvas unraveled itself that I was trying to keep it together, but I’m also the one pulling off the strings.

The final installation is embodying disability as a fluid state or a dynamic disability. especially because, from the outside, I look like an able bodied person. I tied in the themes of weightlessness of being in the water. How do I create my own kind of representation of my body?

My disease that I have really come down to connective tissue. I had just been diagnosed with endometriosis in August of 2020 and had surgery just before I was making this work. I saw some of the surgical photos of dense scar tissue adhesions gluing my organs together, pulling away but also reaching out to each other. As I unraveled the canvas I saved all the pieces of string. It’s hung by pieces of itself from 4 points of a white frame that represents whiteness and falling away from structures of the Medical Industrial Complex. As the air conditioning comes on or someone walks by, the canvas sways, and it’s kind of just barely hanging on.

Below the canvas is a large mirror where only one piece of canvas breaks the reflective plane and touches the mirror, almost as if, like you’re just dipping your toe into the water breaking the surface, breaking that surface of tension.

©Camilla Jerome, I Tried So Hard To Keep It All Together (Walking Study on Mud), 2020, Cyanotype and bathwater on canvas, unraveled by hand, mirror, wood, and monofilament 34” x 84” x 96”. Installation View, Detail, Image description: Looking down at the dark grey cement floor of the instal-lation a large mirror is laying parallel to the floor on top of a white platform. A piece of the hanging canvas falls down and touches the mirror.

MB: Wow, there’s so much richness in all of that, like I’m so glad I asked that question.

I feel like sometimes you have to, you know, let things fall apart to piece them back together, I feel like especially within chronic illness, too. it’s like you have to advocate and spend so much time and labor, you know, to try to figure out what’s going on and then when you were talking about endometriosis I was like ‘Oh, it makes so much sense that you were pulling it apart’, And yeah…It’s really beautiful.

CJ: Thanks yeah my work has always had a really deep conceptual meaning behind it.

So I always love having conversations, too. Yeah, to give insight.

Show Me Where It Hurts, 2020 from Camilla Jerome on Vimeo.

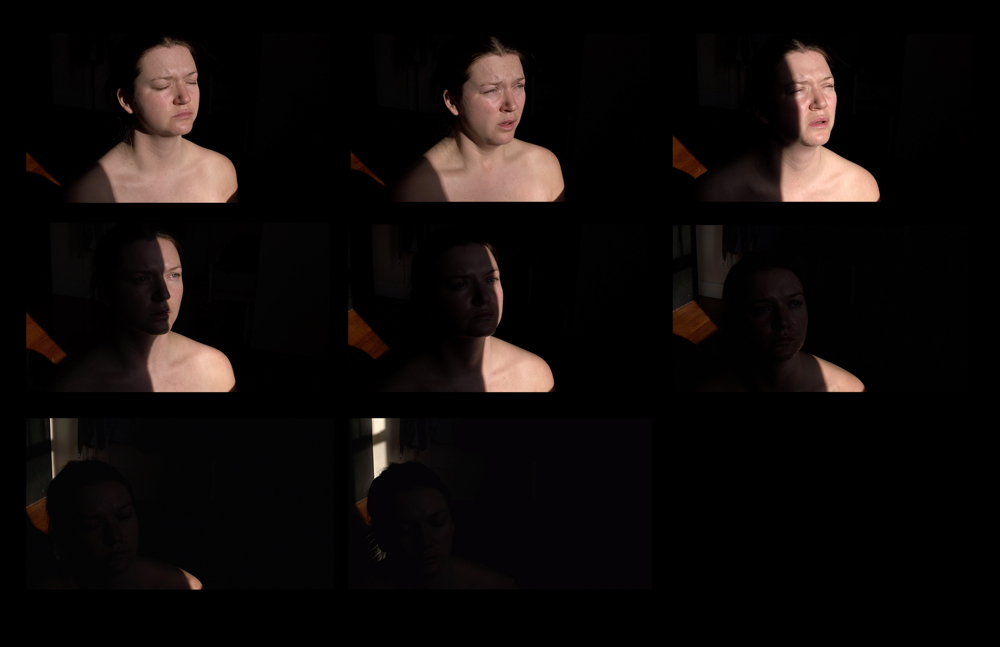

©Camilla Jerome, Show Me Where It Hurts, 2020, 52 minutes 50 seconds, Single Channel Private Video Performance Show Me Where It Hurts, Film-stills, Image description: eight images from a private video performance are arranged on a black page. A white woman’s bust is centered in the frame and is in full sun. For the duration of the stills, she stares into the sun (off-frame). Behind the woman is dark and in shad-ow. As the stills progress a shadow moves from left to right across the woman’s body covering her in shadow.

MB: Another piece I really loved was, Show Me Where It Hurts. I was really captivated by this video. It’s you standing in the sunlight and it’s basking across your body from shoulders up. It looks like you’re looking at the sun and then as time passes the sun moves across your body.There’s a few different things that came up for me watching this. One was that it reminded me of Warhol’s Screen Tests. I didn’t know if that was something you had ever seen. But he saw those as portraits. And I was wondering if you considered this video a portrait of yourself?

CJ: Yeah, I do. If you haven’t caught on a lot I think of most of my work as self-portraits. I love it. Self portraiture has been like from the very beginning, like back to that sophomore year of high school, it was self portraiture that made me finally feel alive. It got me excited, and I wanted to be there. So yeah, you’re right I was staring into the sun. I set out to sit and sit in the window and stare at the sun for however long it took for my body to be completely consumed by the shadow. The piece, in total, is about an hour. It actually stemmed from a class that I was taking on failure with Odette England. The idea of setting yourself up to fail as you watch the video, you can see that I can’t hold my body up for the entire hour. I can’t stay in the same place I end up slumped over in the bottom left corner.

And so I considered, you know, chronic pain, thinking of the pain that I continue to be put in because of the lack of understanding around chronicallity of pain. And it was a really painful experience. It actually hurt my body more than it hurt my eyes. Like opening my eyes, the pain was immediate and knowable. I’ve been there hundreds of times where I open my eyes, and it’s too bright to see. But holding my body up for that amount of time, especially staring into the sun, once that pain had passed. Once. I was, you know, partially in shadow, the pain changed and became a lot more bodily. I’m having a lot of memories flooding back in terms of the actual performance – I lost feeling in my legs, my legs were completely numb by the end of it. So yeah, I don’t think I would ever do it again. I’m in a much different place than I was at that time, too.

At that time, January 2020, I still really identified just more in terms of chronic illness and gendered medical abuse and it was after making this work that I started to slowly identify with being disabled.

Yeah, So some of the elements that come into play – sunlight- is one of my favorite meditative practices, which meditation is a huge part of this sitting and staring performance, and having to breathe and and take your mind away from the pain. One of my visualizations is the warmth of the sun, and having your eyes closed, and you just see red, the inside of your eyelids, and that lovely warm feeling of the sun on your skin. Yeah, I love that feeling. I chase that feeling in the same way that I chase the feeling of floating.

I mean, the sun is a wonderful power, a powerful healing tool. But it can also just do so much damage. Playing on that edge of therapeutic and getting vitamin d, versus burning my retinas or developing skin cancer. Just thinking about the duality of it.

MB: This work, it’s really paired down. It’s just the 2 elements that make photography possible: light and time, moving across your body.

CJ: Yeah, I mean when I teach Intro to photography, one of the first things I tell my students is the breakdown, the root of the word photography, which is, to draw with light. Yeah, and try and practice what I preach. I spoke about my love of the sun and thinking about time with chronic illness.

Time can be suspended in this vastness that feels like forever. Like last year, while I was in it, felt unbelievably slow and like moving through sludge, barely making any headway. But now that I’m here a year later, looking back I’m like ‘Wow! it went by so fast. Look where I am now, compared to where I was a year ago.’ And so I really love that idea of like there really isn’t this one-to-one relationship with time. It’s really just a social construct to keep us at jobs and on time and that just doesn’t work with chronic illness. It runs on its own time, it has its own agenda and so you have to relinquish control in order to have some semblance of sanity. I guess you just kind of have to let time be its own thing.

MB: Yeah, that is something that definitely, when I first started becoming ill it’s like my relationship to time, just completely changed. You know?

CJ: Yeah, it’s really really wild, yeah really wild. How something can be only a day and it feels like a year but a week can feel like seconds? So I think that’s kind of just like a low lying theme throughout the work that I think a lot about. I’ve been slowly picking through a book by Carlo Rovelli, The Order of Time. I’ve been picking through it, and trying to make sense of time and physics.

MB: Even like how the photon lives in duality, you know. It can be a particle and a wave.

CJ: Yeah, it’s like everything about the process really is fluid, you know. I really feel that with photography because there are just so many ways to approach a photograph. If so, and that’s one thing that you know I tried not to limit myself in terms of what I was being called to make with. The fluidity of being able to make pictures with my phone or the list of cameras that I mentioned earlier, or to be printmaking with light and time, different ways of using photography and alternative processes. That’s like one of my favorite things about photography – its ability to just completely blow my mind and to make something that I’ve never quite seen before.

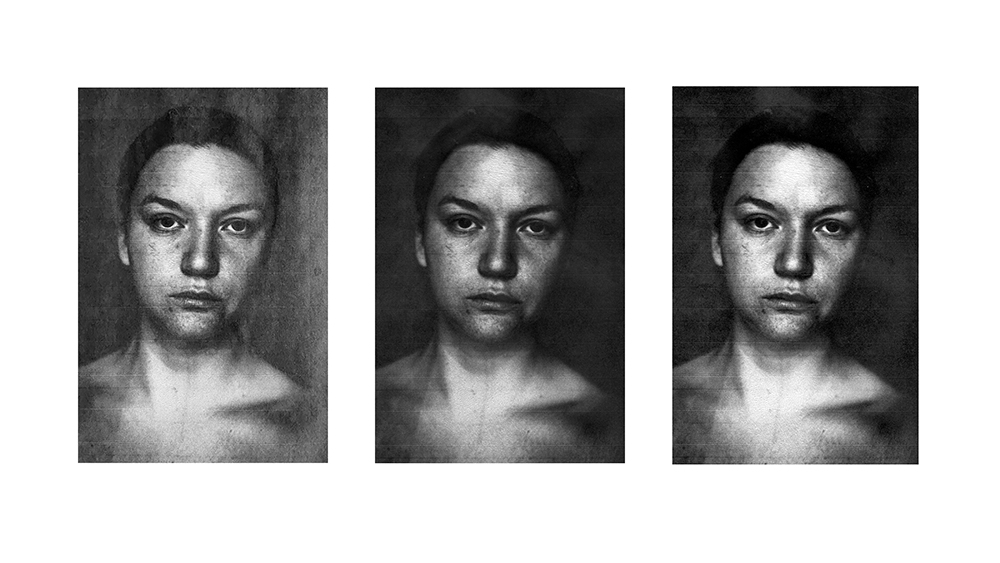

©Camilla Jerome, Diagnosis, Self-Portrait, 2020, Inkjet Print, Rescanned 2021 and 2022. Image description: Three versions of the same self-portrait of a white woman are together on a white page. There is a tight crop on the artist’s bust and face in front of a blank gray background. Her hair is up and she is staring into the camera, head slightly tilted right. Her pupils and iris are dark with no catchlight reflected. The image is “grainy” and has banding from the printer that runs horizontally through the entire image at every inch. The image darkens and the woman’s outline of her body be-comes more indistinguishable from the background in the re-scanned versions of the same portrait.

MB: Can you share with me about the process for Diagnosis?

CJ: It’s a self portrait that I made 2 years ago now. I needed to make a print, and I only have, like a kind of crappy inkjet printer, it was like $75, and the ink is now more expensive than the actual printer. so, I printed the self-portrait on conventional printer paper with black ink, and the first time I printed it, I was a ghost like there was no pigmentation in my skin, consumed by whiteness and so I had to keep feeding the paper and reprinting the portrait over and over again.

And it took about 5 prints until there was legibility with skin gradation. And then I got to the point where my hairline almost blends into the background, because it’s kind of the only thing that had any density to it. So the final print, it’s not archival, the image continues to change and I rescan it every year.

MB: Wow

CJ: So yeah, I’m back to do my third scan of it. And it continues to darken over time. And I think about the way that my name and my birthday, and all of this data has been repeated so many times and printed over and over again, and all the images of inside my body. They never contain my face, and who I am, my identity and that’s been a really important piece, and I haven’t quite known what to do with it other than to save it and keep scanning it every year.

Yeah, there’s another thing that’s coming to me about photography and illness. For a time I thought photography had failed me. The most high tech diagnostic imaging of X-rays, MRIs, CT scans never showed what was actually happening inside of my body. There was never any evidence on those scans of my organs that were glued together with scar tissue. And so in that sense, photography never properly conveyed what was happening. That’s because I didn’t have autonomy over the way that the images were being made, and so how do you show something that’s invisible? I think we all kind of think about this a lot as visual artists through a lot of different contexts. But you know, back to my diseases and really thinking about how complex connective tissue disorders are. They are so under the radar, and they don’t show up on imaging. How can I show that with photography? And then that kind of comes to the multitude of formats that I started to just let loose. Use them and think back that photography hasn’t failed me. It hasn’t. It’s been there all along. It’s just who’s holding a camera.

MB: Exactly. Yeah, Yeah. And it’s interesting to think about how photography is one of the diagnostic tools to give us, what’s the word i’m thinking of, validity right? You know it’s like you know something’s wrong for so long, and you keep saying it and so the photography is supposed to be this tool that allows people to believe you. But then there’s also sort of like this really beautiful sense of you reclaiming with that same medium.

CJ: Yeah, yeah, I guess it’s so wildly poetic that I don’t think I can even just like I mean I love. I love poetry, and I write a lot of poetry. So it makes me excited to think about some of those things like those are things you just those are things you read about. Yeah interaction between one media and different ways of imaging the body. Or my body, I don’t like to use the term the body, because no one’s body is the same. So I needed to correct myself, my body, imaging of my body. (Read: Why I Don’t Talk About ‘The Body’: A Polemic, by Gordon Hall)

©Camilla Jerome, Untitled, Post-op, 2020, Archival Pigment Print Image description: A close-up and vertical color photograph of a white woman’s abdomen. The sun-light is warm, falling from right to left, and projecting a shadow of a windowpane cross onto the right side of the stomach. The underside of her breasts is at the top of the frame. At the bottom of the frame are a hint of pubic hairs and a small scabbed-over incision. At the center of the frame is her belly button bruised with purple and yellow markings, there are remnants of adhesive creating brack-ets around the belly button.

©Camilla Jerome, Untitled, Snake Skin, 2020, Archival Pigment Print – Image description: An abstract and horizontal color photograph of water. The light is refracted into yellow marbling that weaves around dark green shadows. In the center of the frame, there is a grey snakeskin floating in the water.

MB: I was curious to learn who are some of your artistic influences.

CJ: I’ll start like more historically, yeah. So Ana Mendieta has been a really big influence in my work. Pieces and projects that she worked on so thinking of the videos that she made putting her body into nature. You know, there’s one video of her laying in a creek, and she’s on her stomach, and her head is turned away from the camera. But you can see that she’s holding her head up so she doesn’t drown. I was just thinking about me laying there, and how uncomfortable holding your head up like that. And I can feel the pain running down my neck and thinking again, time, light, water.

And then some of her later work where she started to make sculptures of the female form and of vaginas in the sand, and the temporality of making a structure that’s just gonna wash away. And it only exists for this certain period of time, that’s something I’ve held onto, that work, because she specifically has been very influential.

In terms of psychoanalysis, Carl Jung. It has really blown my mind. And I really like to think about the 3 states of consciousness. So you have consciousness, the subconscious, and the unconscious. Consciousness and unconscious come and go like that’s kind of like your it’s one or the other. But the subconscious is always present and I really appreciate the work that he did.

Another historical figure would be Emily Dickinson, and I can share the specific poem with you, We Grow Accustomed to the Dark. But well thinking of, you know, in a historical context of looking at Emily Dickinson as someone who probably had chronic illness, their records of epileptic episodes, and then through her writing and her relationship to life and death. And the relationship to her work to the body, and I’m not entirely sure if it was on purpose. But her work was largely unpublished while while she was alive, but she made these series of of books of her writing that were pages folded, multiple series of books.Then they were bound with red twine, and she called them fascicles, and that the root of the word traces right back to the body of being connective tissue, and having, like different fibers of the body, that run together and so that’s what she was calling these books, and I just, I wish she was alive. I’d love to have conversations with her.

And then some more contemporary artists, Eleanor Carucci has been a big influence in my work for a long time, her generosity and honesty with the camera, and Cig Harvey. I’d get critiques a lot that some of my work is too beautiful and just I love how Cig lays into the beauty, and like, why can’t my work be beautiful? In thinking about how disability and illness is beautiful, I think about the caregiving between me and my husband, and the things that he has to do to help me, the intimacy of our relationship that I don’t think anyone else could fully understand or experience. I’m so grateful to be able to trust somebody on that level, and be that open with them. It’s beautiful and I just love Cig’s work for that, for just getting lost in the beauty of things. Getting lost in the beauty and wonder of the world. So those are some of my big hitters.

MB:I like that, the rejection of the critique of the beautiful in photography.

Yeah, I mean, I definitely ate away at me for like a really long time. But then again, then it comes back to what I was saying in the beginning that there are equal parts therapeutic and aesthetic. They hold each other up, and neither one of them has to give anything or be sacrificed. But you know they’re there to amplify each other.

MB: My last question is, what is currently happening with your work? What are you working on now? And you there just like anything new and upcoming that you want people to know about.

CJ: Yeah I’m always making work, it’s definitely shifted. What I had kind of planned for my career isn’t so much a reality, for me right now. Like the physicality of having to leave the house, navigate campuses in order to teach, or you know, I’ve had a long commercial career but being on set it’s just not it’s just not realistic. I’m trying not to push my body too far. I think I’ve learned my lesson in Grad school of how far I could push it before making things worse. And so it’s a really fine line, I’m really trying to figure out what does my life look like, and what and what am I going to make with this different path?

So I am slowly building a business of making cyanotypes. I kind of fell into making work that are unique pieces. There is no replica of the work and that’s kind of where I Tried So Hard To Keep It All Together finds its place. I have some other things that I worked with bleach and prints, and so that’s a you know a unique object it’s just that one print that looks that way. And so I have been making cyanotypes like this one here using flowers that are sent as like Get Well Soon (I won’t) or Condolences and making one-of-a-kind prints where you own the original. I’m making art accessible. Instead of like, you know, I saw something and Target like a little while ago, and it was like blue and white patterns, and I was like ‘That’s literally a cyanotype’, but everybody is now gonna own this same piece.

I’ve really fallen in love with the color blue. I read Bluets by Maggie Nelson, and it is a beautiful book that really challenged my way of thinking about the way that you can write. It’s written in kind of a list form so each passage is numbered. And so I started thinking about the relationship between blue and disability. Thinking about why all signage for disability is blue. And all I can come back to is the way that light travels and the way that color travels. The contrast that blue can make blue and white, blue and yellow, that can make it stand out from a distance.

I’ve really fallen in love with the work of artist Shannon Finnegan, who makes benches and chaise lounges and stools, and I was just like this is like this is brilliant. I love it. I love the idea of sitting and it’s something that I’ve a lot about in my work and the need to rest. Yeah. kind of wondering why I was like not going to shows or museums and things like that. And it’s really because it’s just exhausting yeah, And so I really love the way that they are pushing against. Pushing against ableism.

MB: I love their work, too.

Yeah, I saw it, and I was like, ‘Oh, my God, this is absolutely amazing.’ Yeah, I was almost borderline jealous “damn it why didn’t I think of this?!” It’s so good, it’s so good but the way that they fabricate their pieces, and they’re just getting more and more sophisticated, and they’re directly changing and stuff so i’ve really enjoyed that work.

At first I was like I really was forcing myself to like the color blue and then, and then I just felt like I fell right into it and now I can’t get away.

MB: Oh, thank you so much, I’ve been following your work for a while. I’m really glad that we got to connect in this space and that I got to learn more about your practice.

Yeah, thanks. Thank you so much. I know it’s nice to finally meet virtual friends and actually sit down and have a conversation that’s not just like insta messages back and forth.

Megan Bent is a lens-based artist interested in the malleability of photography and the ways image-making can happen beyond using a traditional camera. This interest started to occur after the diagnosis of a progressive chronic illness. Drawn to image-making processes that reject perfection, accuracy, or any certainty in results, she is interested instead in processes that reflect and embrace her disabled experience; especially interdependence, impermanence, care, and slowness

Her artwork has been exhibited nationally at The Halide Project in Philadelphia, PA, The Center For Fine Art Photography in Fort Collins, CO; The East Hawaiian Cultural Center/HMOCA in Hilo, Hawai’i; Flux Factory in Long Island City, NY; El Museo Cultural, Santa Fe, NM; The Foster Gallery, in Dedham MA; Soho Photo Gallery in Tribeca, NY; the Austin Central Library Main Gallery in Austin, TX, and internationally at F1963 in Busan, South Korea; Alternative Space 298, Pohang, South Korea; and Fotosotrum in Barcelona, Spain.

She is currently an artist in residence at Art Beyond Sight’s Art + Disability Residency and has been an artist in residence at the Nobles School in Dedham, MA, and the Honolulu Museum of Art, HI. She has presented her work at Atlas Obscura: The Secret Arts, The Pacific Rim International Conference on Disability and Diversity in Honolulu, HI, at Other Bodies: (Self) Representation, Disability and the Media at the University of Westminster in London, U.K., and at Critical Junctures at Emory University in Atlanta, GA. Her work has been featured in Analog Forever Magazine, Fraction Magazine, Too Tired Project, Rfotofolio, and Float Photography Magazine.

Follow Megan Bent on Instagram: @m_e_g_g_i_e_b

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026