The Dynamics of Photography and Disability: Jameisha Prescod

©Jameisha Prescod, Image description: A photo of Jameisha wearing a black top. Jameisha is a Black person with dark brown skin. She has a nose piercing and is wearing her hair in a low bun.

This week we are looking at projects by disabled/chronically ill photographers. The definition of dynamics is “forces or properties which stimulate growth, development, or change within a system or process.” Each of these artists is approaching their work in ways that embrace this meaning, enacting change and raising important questions about societal systems through their ideas, craft, and processes they use.

Jameisha Prescod is a London based filmmaker, artist and chronic illness advocate. Driven by storytelling, they apply creative digital techniques to uncover powerful hu-man experiences. Jameisha specialises in documentary and video journalism while also exploring audio production and poetic diary films.

After being diagnosed with lupus, Jameisha founded You Look Okay To Me, the online space for chronic illness. She explores the social and cultural aspects of living with a chronic condition through visual mediums. Since the project’s inception, the communi-ty has grown to over 28,000 people online.

“Stories are the most powerful agent of meaningful change. As an artist, I use creative mediums to uncover stories about illness, disability and how these themes collide with race, gender, sexuality, and religion. I want my work to give an intimate and transpar-ent insight into the aspects of disability that aren’t widely told.” – Jameisha Prescod

Megan Bent: Welcome Jameisha. To start, could you please tell us a little about yourself?

Jameisha Prescod: Hey! My name is Jameisha Prescod. I’m a London-based filmmak-er, writer and artist. I’m also the founder of an online space for chronic illness called You Look Okay to Me. The majority of the work I do focuses on illness, disability and identity. I’m fascinated by human stories and try to explore this as much as I can through different artistic mediums.

©Jameisha Prescod, Image description: A photo of Jameisha sitting on a kitchen counter in front of a window. The kitchen is dark and the window casts Jameisha completely in shadow.

MB: How did you get into photography? What compels you about the photographic medium?

JP: I got into photography at quite a young age. I always loved those little disposable cameras and got excited to see how all the photos turned out. I grew up extremely shy and insecure about my looks, so I started taking photos to avoid being on camera. As time went on I started enjoying how creative you could be with the medium. Eventually I transitioned into moving images and stopped taking stills as much. Recently in the pandemic, photography is something I’ve returned to. A lot of my recent work consists of self-portraits which feels like I’ve come full circle.

I love the photographic medium because it is a powerful vessel for storytelling that allows you, the photographer, to use creative techniques to communicate a story to the viewer while still leaving your work open for interpretation.

©Jameisha Prescod, Image description: A photo of Jameisha sitting in the bath looking at the camera. Jameisha is a Black person with dark brown skin. White tiles with decorative floral designs can be seen in the background.

©Jameisha Prescod, Image description: A photo of a projection on a bedroom wall. The projection has a white background and black text that says “”I’m disabled” is the phrase that set me free.”

MB: What does disability mean to you and to your work?

JP: Disability is the leading theme in my work. It’s a theme that I find to be underrepresented in the art world. It’s especially underrepresented when it comes to having disabled artists lead the charge for exploring disability in art. Disability is so diverse, especially when we look at how it intersects with culture, race, religion, sexuality and gender identity.

MB: I have been following your Instagram, You Look Okay To Me for a while and I just love it. What compelled you to start You Look Okay To Me?

JP: I was diagnosed with Lupus a few days after my first day at uni. I originally wanted to be a cinematographer, but my entrance into the film world wasn’t great. Most film shoots were not accessible for me. There are days where I could barely get up to go to the bathroom, yet I was expected to be a runner on set for 16 hours. I find it really disheartening to know that my aspirations may not happen for me.

The summer of my first year I decided to start a project that allowed me to creatively express myself with visuals while educating people about what I and many other people were going through. The rest is history I guess.

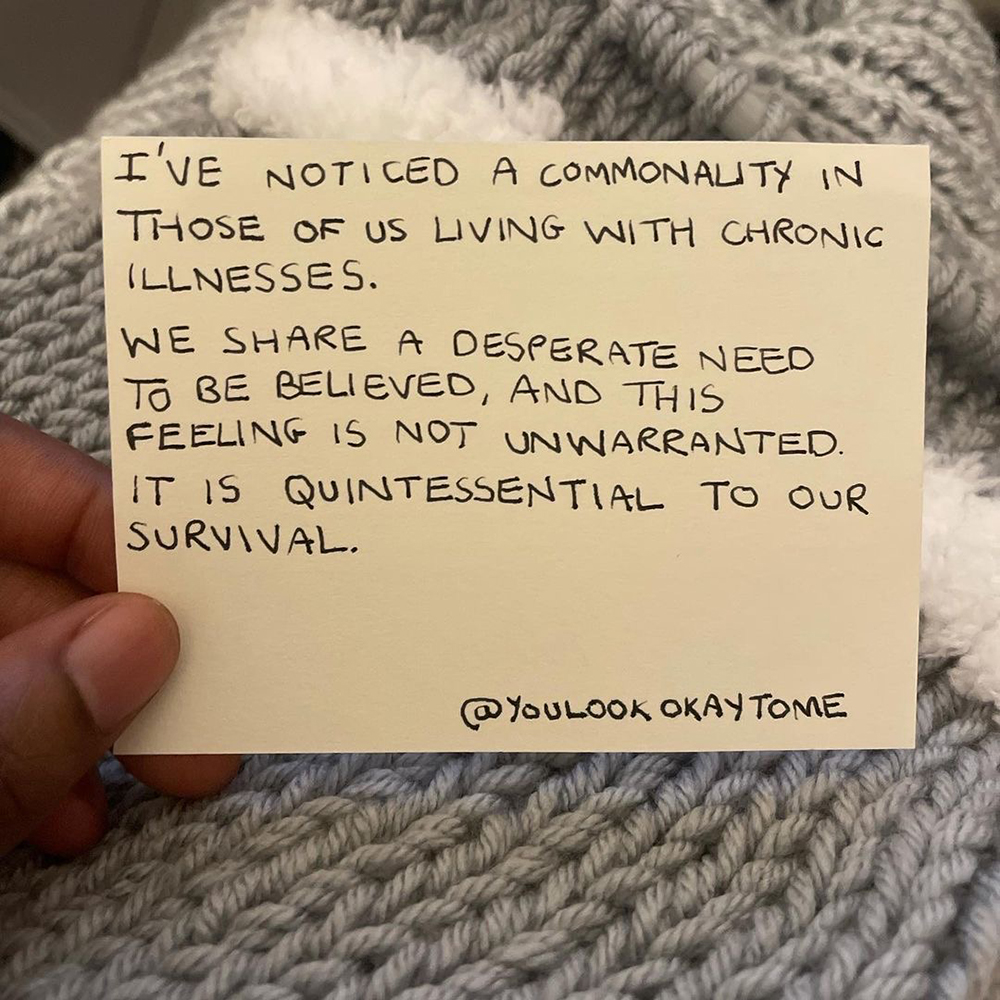

©Jameisha Prescod, Image description: A photograph of Jameisha holding up a piece of card with black handwritten text on it that says “I’ve noticed a commonality in those of us living with chronic illness. We share a des-perate need to be believed, and this feeling is not unwarranted. Iit is quintessential to our survival.”

MB: What has it been like to have an online platform and help build community with disabled people?

JP: To be honest it’s both amazing and terrifying. I love the community I’ve built online. I’ve made lifelong friends across the world and have a space where people feel comfortable to share what they’re going through. I’ve been trying to make it a space where people with chronic illnesses and other disabilities feel like they can be honest and transparent.

At the same time, I’m still that shy girl I used to be, and the idea of 28,000 people wanting to know what I have to say about something makes me feel anxious and sometimes unworthy of the support I get. But I’m working on that in therapy.

I spent the early days talking about my personal experiences, but this year I’m hoping to aid in telling more stories from other people’s perspective.

©Jameisha Prescod, Image description: A photo of Jameisha’s hands holding a photograph of their grandmother holding them as a newborn baby.

©Jameisha Prescod, Untangling, 2021 Image description: A photograph of Jameisha knitting in their messy bedroom. Jameisha is a Black person of Afro-Caribbean descent with dark brown skin. Jameisha is wearing a teal headwrap, a Pulp Fiction T shirt and a navy blue tartan skirt. In their hands, they hold a strip of white, blue and grey knitted fabric.

MB: Congratulations! You recently won the Wellcome Photography Prize, with your image Untangling. Could you share about making that photo and what it meant to you?

JP: Thank you! Untangling winning that prize has felt unreal most days. At the beginning of 2021 I was feeling extremely low. I’d recently had a bad experience with surgery and was struggling with yet another lockdown in the UK. Whenever I get stressed I stop doing basic tasks, so my room accumulated a mountain of mess which is a big source of shame for me. One thing I found myself doing amongst the chaos of my room was knitting, a skill taught to me by my nan. It’s a way of soothing the stress and periods of low mood I was going through.

One day I had the idea to capture this in a photo. The process of taking the photo was pretty quick. I climbed over some of the mess, put the camera on a tripod and took the shot with a timer.

©Jameisha Prescod, Image description: A photo of a dark bedroom with a white square projected onto a wall with black text that says “Recovery often takes longer than we think.”

MB: Recently you have been sharing images on You Look Okay To Me that I find very resonating. In the images, you are projecting words onto a blank wall above your bed. Could you share more about that series? What has the public response been like?

JP: I guess I’m always thinking about ways to say stuff that’s creative but also intimate and personal. I recently bought a projector from Amazon for a separate project that never came to be. I’m a big fan of Instagram accounts like @werenotreallystrangers who edit words onto the side of buildings with profound statements. I wanted to do something similar specifically relating to illness and felt like the projector was a cool way to do this.

The response so far has been good mostly! What sometimes feels like a simple statement seems to resonate with people that need their feelings to be validated. In a way, those people letting me know how much it affirms them makes me feel validated also. Less alone.

©Jameisha Prescod, Image description: A photo of Jameisha’s hand holding up a small rectangular white piece of paper in their bedroom in front of white net curtains. Written on the piece of paper in black text it says “to be-lieve your pain is real is a radical act of self-care.” Jameisha is a Black person of Afro-Caribbean her-itage with dark brown skin.

©Jameisha Prescod, Image description: A close up photo of Jameisha sitting in the bathroom. Large white tiles can be seen in the background. Jameisha covers their face with their hands. Jameisha is a dark skinned black person of Afro-Caribbean origin. They are also wearing long black braids tied back in a bun. Jameisha’s left shoulder has a bit of soap suds on it.

MB: Who are some artists that have influenced you or inspire your art practice?

JP: I think if I listed them all, we’d have to publish a book. When I’m inspired by different artists it’s often not about the style or medium, but more about how it made me feel. I love Frida Kahlo’s work. She is a huge inspiration for me and also one of the reasons I’ve been exploring self-portraits documenting my pain. I also love Steve McQueen, especially his earlier pre-mainstream cinema video artwork.

©Jameisha Prescod,Image description: A photo of a dark bedroom with a white square projected onto a wall with black text that says “Maybe it’s not just a bad period.”

MB: Is there anything new or upcoming you would like to share with people?

JP: Yes! I have a short film that’s almost finished coming out (at some point). It was funded by Unlimited Arts and is called Do I Look Okay to You? A short essay piece telling three stories of Black people in pain. Hopefully I can create more stuff like this in the future.

Megan Bent is a lens-based artist interested in the malleability of photography and the ways image-making can happen beyond using a traditional camera. This interest started to occur after the diagnosis of a progressive chronic illness. Drawn to image-making processes that reject perfection, accuracy, or any certainty in results, she is interested instead in processes that reflect and embrace her disabled experience; especially interdependence, impermanence, care, and slowness

Her artwork has been exhibited nationally at The Halide Project in Philadelphia, PA, The Center For Fine Art Photography in Fort Collins, CO; The East Hawaiian Cultural Center/HMOCA in Hilo, Hawai’i; Flux Factory in Long Island City, NY; El Museo Cultural, Santa Fe, NM; The Foster Gallery, in Dedham MA; Soho Photo Gallery in Tribeca, NY; the Austin Central Library Main Gallery in Austin, TX, and internationally at F1963 in Busan, South Korea; Alternative Space 298, Pohang, South Korea; and Fotosotrum in Barcelona, Spain.

She is currently an artist in residence at Art Beyond Sight’s Art + Disability Residency and has been an artist in residence at the Nobles School in Dedham, MA, and the Honolulu Museum of Art, HI. She has presented her work at Atlas Obscura: The Secret Arts, The Pacific Rim International Conference on Disability and Diversity in Honolulu, HI, at Other Bodies: (Self) Representation, Disability and the Media at the University of Westminster in London, U.K., and at Critical Junctures at Emory University in Atlanta, GA. Her work has been featured in Analog Forever Magazine, Fraction Magazine, Too Tired Project, Rfotofolio, and Float Photography Magazine.

Follow Megan Bent on Instagram: @m_e_g_g_i_e_b

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026