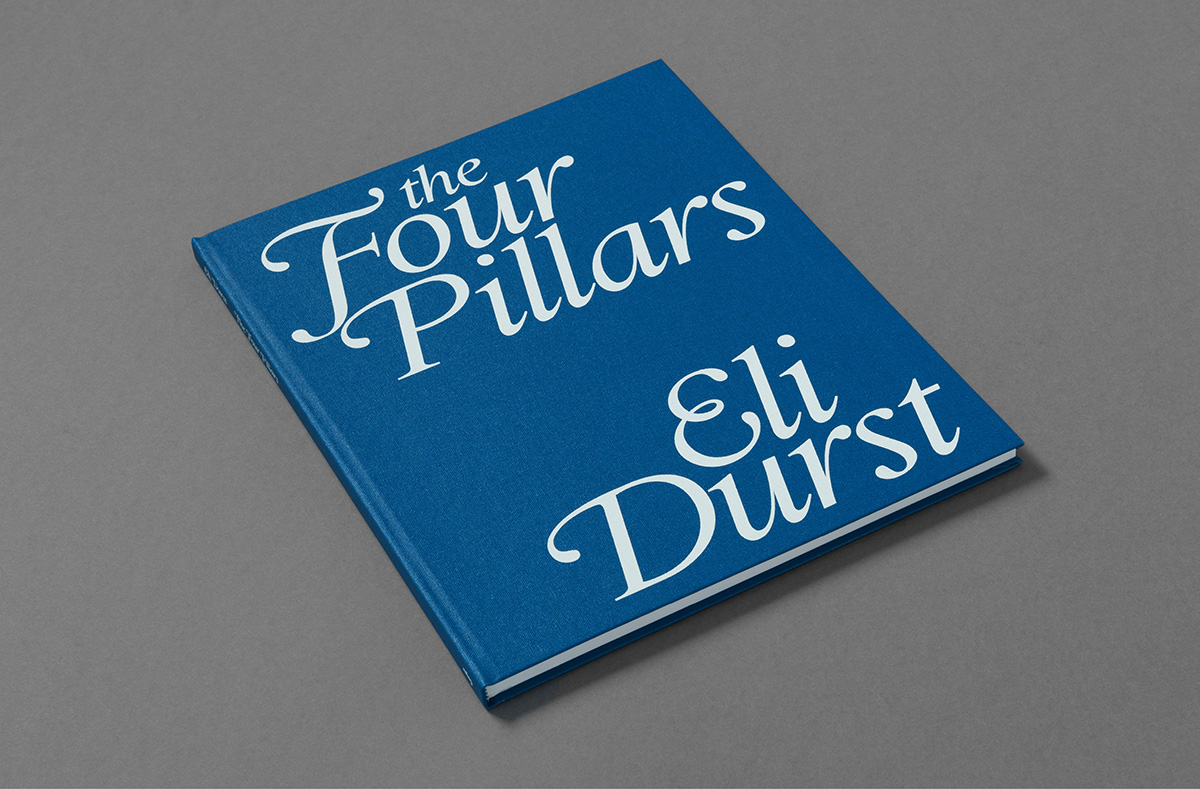

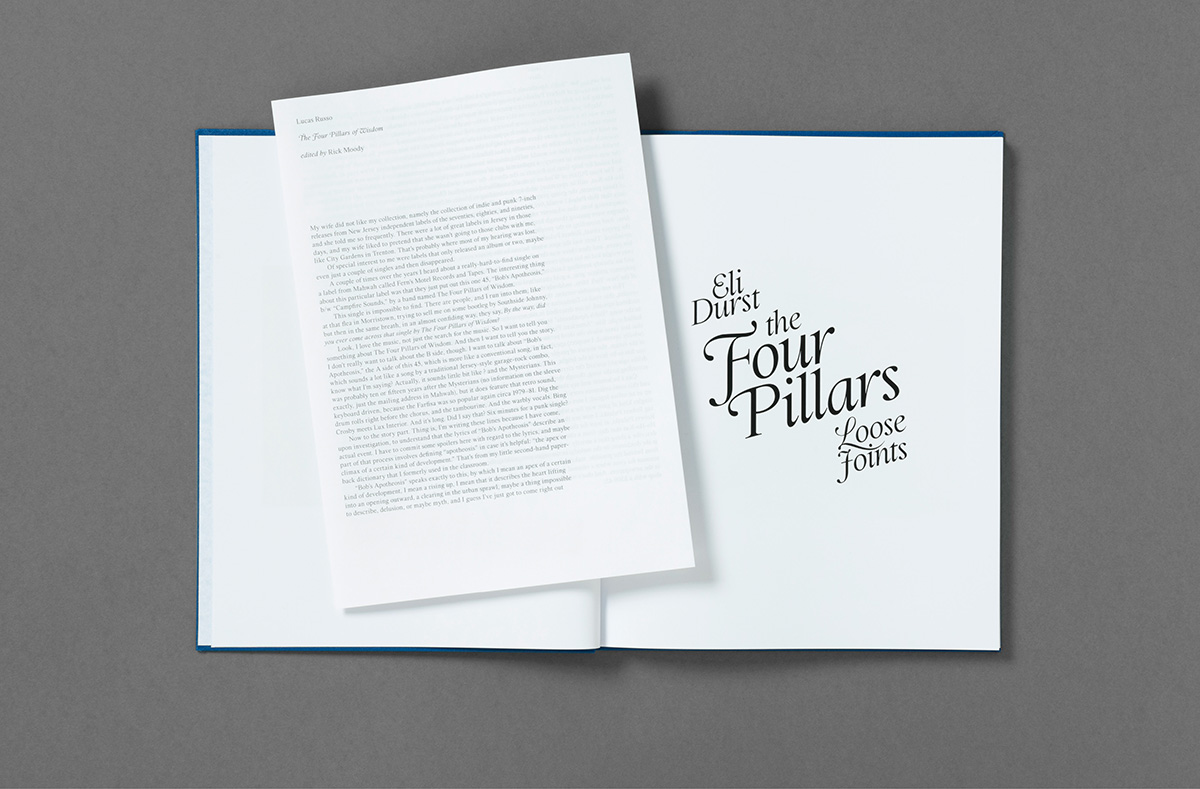

Eli Durst: The Four Pillars

The Four Pillars, Eli Durst’s newest photobook published by Loose Joints, grew out of a relationship with a faith-based self-help group that Durst photographed over several years. Despite their ostensibly comfortable lives, these affluent suburbanites felt unfulfilled and directionless. They met weekly in church basements to discuss spiritual and secular strategies to find meaning and purpose, and to deconstruct the markers of success, progress and identity within middle-class American society.

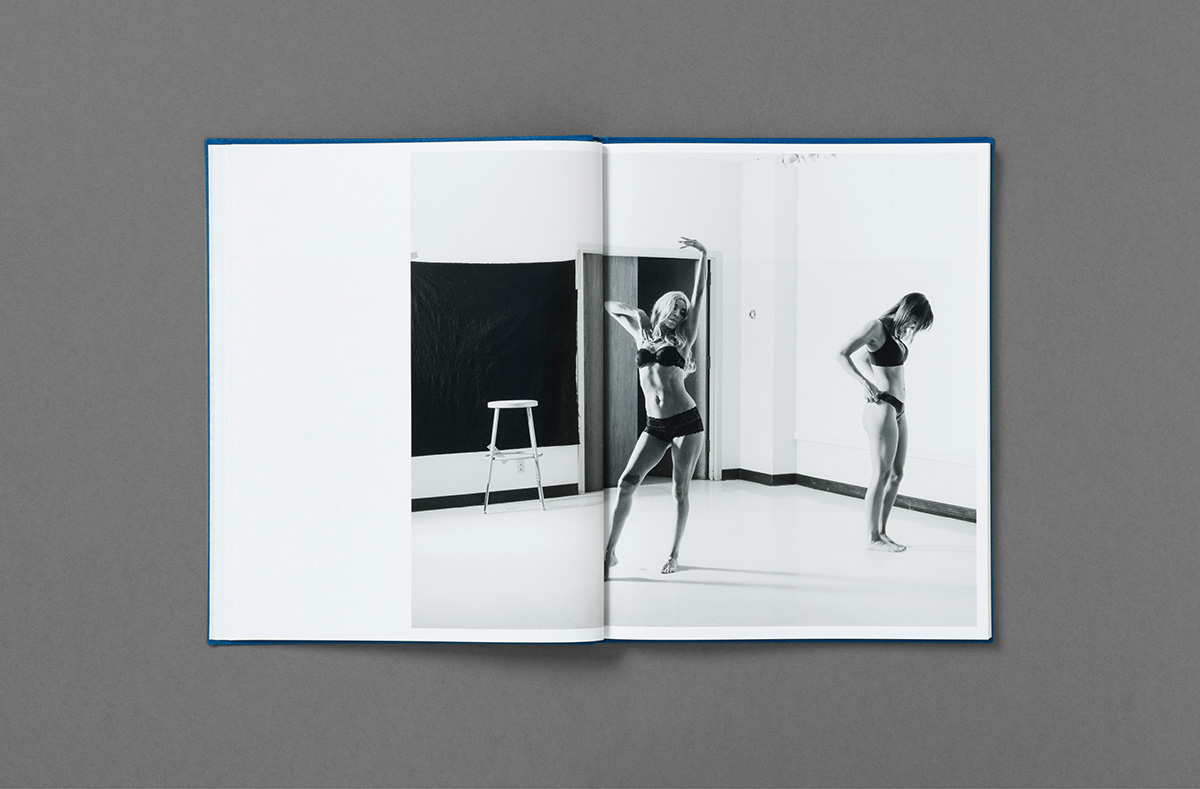

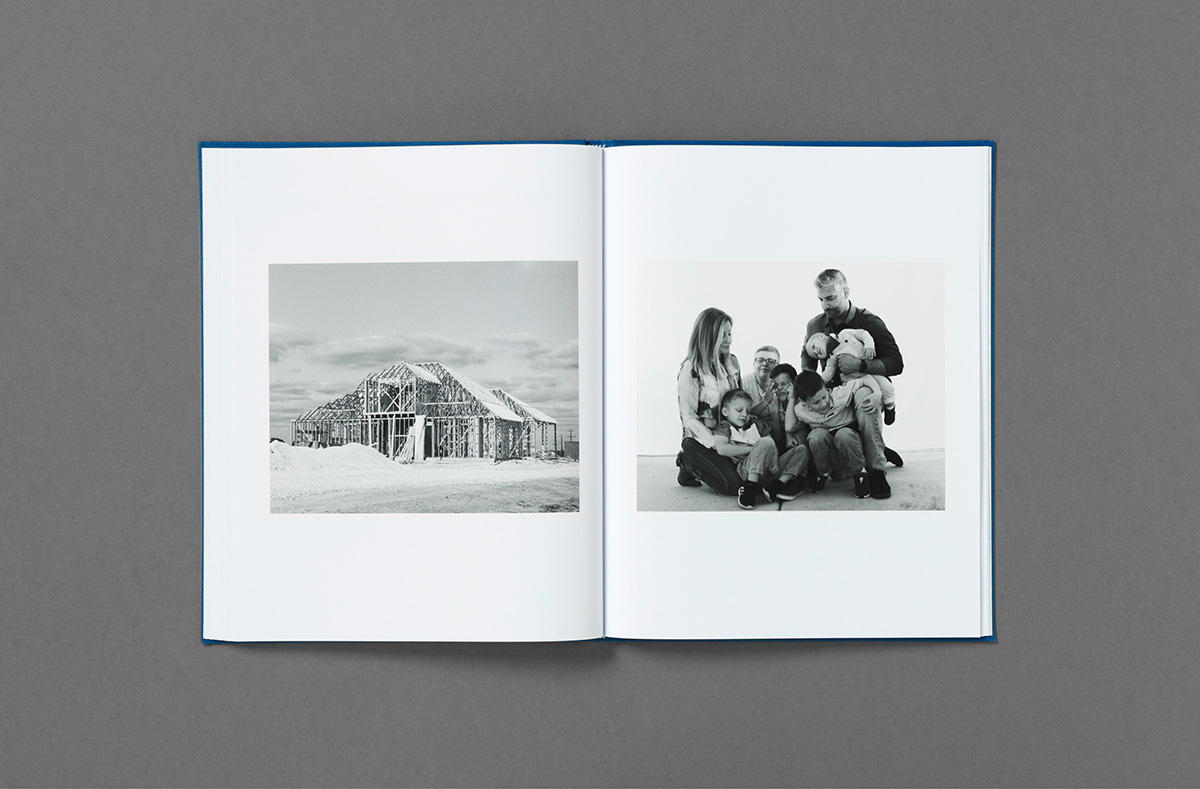

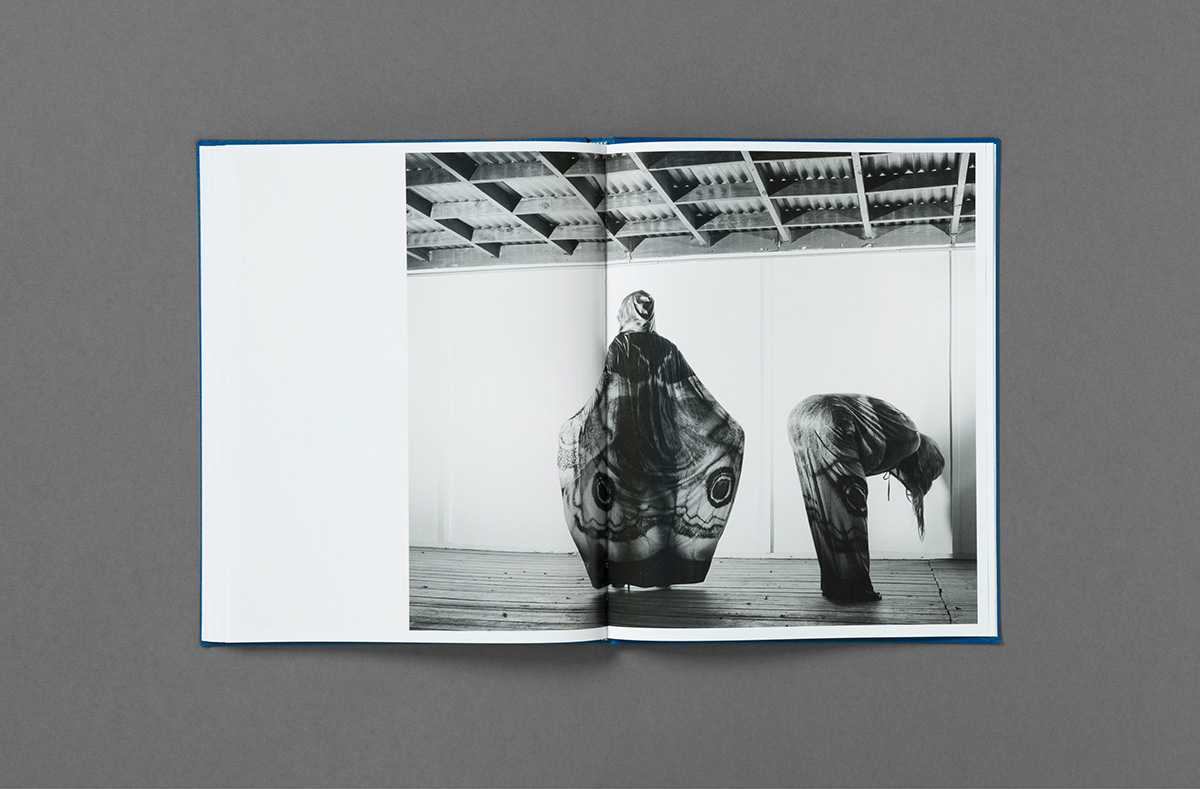

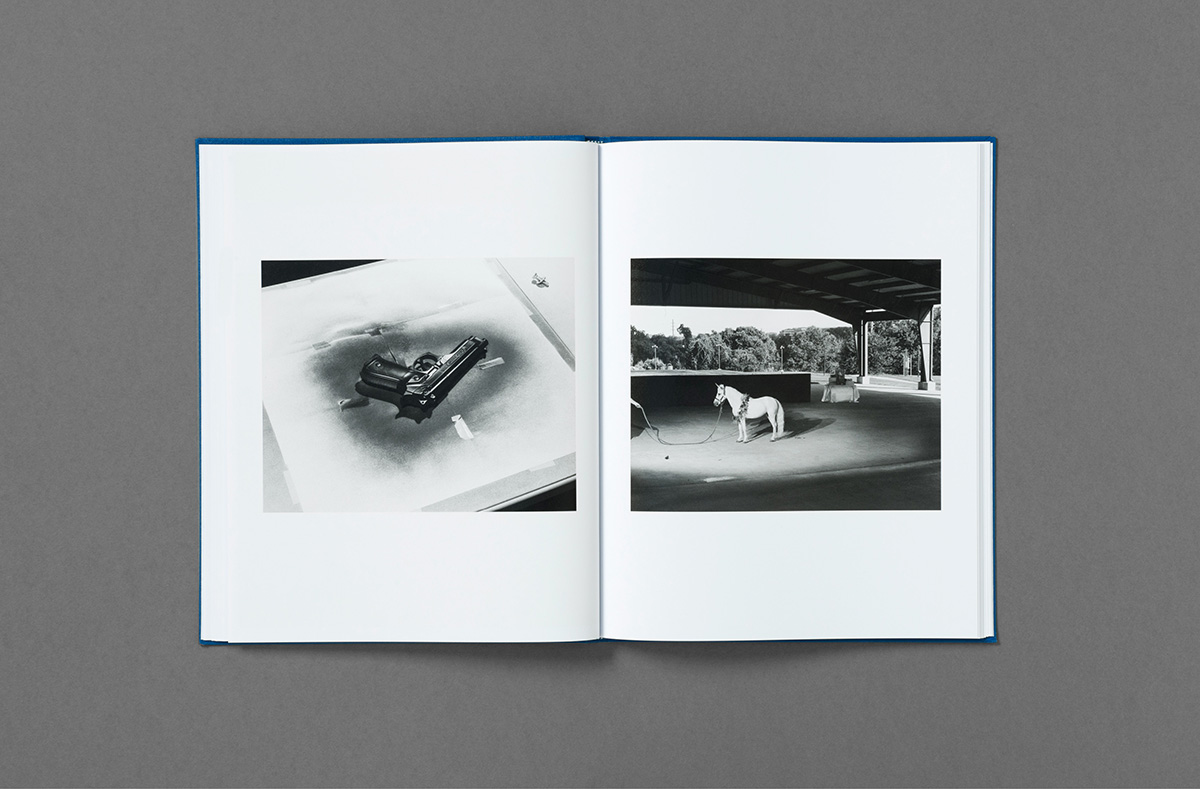

Durst’s staged, inventive images build organically on this self-critical base structure by inventing scenarios that interrogate the relationship between the individual and the group, the norms we aspire to, and the social gravity that holds these two in alignment. Durst takes the details of these scenarios – mundane family portraits, team bonding exercises, pregnancy groups, school gyms, amateur theater, county fairs – and amplifies their strangeness, through a lens that is at once factual, fictional, banal and absurd.

The following is a conversation between Tracy L Chandler and Eli Durst as they discuss the making and meaning of The Four Pillars.

Eli Durst was born and raised in Austin, TX. After graduating from Wesleyan University in 2011, he worked at the renowned fine art printing studio Griffin Editions in Brooklyn while also serving as an assistant to street photographer Joel Meyerowitz. Eli received an MFA in photography from the Yale School of Art and is the winner of the 2016 Aperture Portfolio Prize, a 2017 Aaron Siskind Individual Photographer’s Fellowship Grant, and a 2019 New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship. He currently lives in Austin, TX, where he teaches photography at the University of Texas. Eli’s first monograph, The Community, is available for order at morelbooks.com

Follow Eli Durst on Instagram @durzt, Follow Tracy L Chandler on Instagram: @tracylchander

Tracy L Chandler: This work comes on the heels of another body of work, The Community, in which you also explore groups of people in acts of collective self realization. How does The Four Pillars evolve that previous idea?

Eli Durst: The Four Pillars grew out of my first book, The Community, where I was working primarily in church basements and community centers. These spaces are mundane, functional, and accessible but they also feel charged. I’m Jewish. I grew up in Texas, a very conservative, very religious, very evangelical state. There was something alluring to me about these spaces. At first I was photographing bingo, bible classes, boy scouts and I realized pretty quickly that the Americana thing was not the direction I wanted to go and I zeroed-in on the more spiritual activities, witnessing the attempt at self improvement and self actualization. I was interested in that attempt at transformation. I found a non-denominational New Age group of people in Newtown, Connecticut, whose mission was focused on healing. I worked with that group to make The Community. I like to think of it as a primary source document that became the springboard for The Four Pillars. Where The Community is more like a documentary, The Four Pillars is more like a narrative film. The feel of The Community is very much indebted to a documentary style of photography and in The Four Pillars I am interested in subverting that language and its relationship to truth. This work is much more deliberately constructed.

TLC: Even though the photographs are more crafted, they are still borrowing from that same traditional documentary language with your use of B&W, flash, etc. The viewer is forced to ask themselves what is “real” and what is “staged.” But we both know that line is blurred in every photograph. Photographs are always a subjective part-truth.

ED: Yes, some of these are staged and some are totally candid. It gets interesting when we don’t know which is which. I am interested in what exists between the photographs, what it means to put something believable next to something totally unbelievable.

TLC: The book opens with an image of a folding table with 3 sheet cakes sitting in a row, each with the notable absence of a recipient or sentiment usually spelled out in colorful icing. It’s as if the celebrated occasion has been abandoned or maybe yet-to-be-determined. I am immediately struck by these voids. They seem like blank slates yet to be filled with humanity and drama. I am wondering if this is a point you are trying to make with this work. Do we as humans feel inherently empty and feel the need to do something or be something more than we already are?

ED: I love the cakes as a starting image because it is like the story is yet to be written. Maybe that sounds cheesy but it’s really the idea that we can’t live without culture. If I was born 200 years ago, I wouldn’t have been me, I would be totally different. We are like these blank slates that get written on. The work of self actualization is, in some sense, a reckoning of the personal and the cultural. There is a deconstruction that needs to take place, coming to terms with all of the things I was told that I should want, that I should be, how I should act, who I should desire, all these things.

TLC: Throughout this work, you portray groups of people interacting in semi-public spaces. The location in each picture is comfortably familiar with all trappings of generic suburban America; community centers, meeting rooms, parking lots. Yet the action within them is always a bit off, slightly strange, like we popped in just before or after things got really weird. Is there something for you in that liminal transition space that says more than showing the thing itself?

ED: This is something I talk about with my students all the time. They’ll go to an event and it’s like, okay, here’s the skateboarder, doing the trick. Here is a picture of an ollie. But we’ve seen that so many times. It’s a version of the action itself, the event itself, which is made to be seen. It’s made to be observed. I am more interested in the construction of that moment. There is a performance that is happening but I am not photographing the main event, the show, the thing that is meant to be seen, but the construction of it.

TLC: Your subjects seem to be involved in acts of performance, staging dramas or rituals of transformation. Whether it be a form of pageantry, theater, prayer, or therapy, there seems to be a common agenda of self transformation. But there is also a futility in the air, like once that costume comes off, we are still left with our same old self. Do you have any personal experience with seeking transformative encounters within a community? How did you go about choosing and/or staging these specific subjects and performances?

ED: So I should say that I’m definitely not a member of these groups but some of the photos are personal. They are related to my family in some way or have other personal connections. This is not about my specific journey or experience, but I do think this idea of self help is ubiquitous. It’s such an American thing, right? This idea that if you’re unhappy, you can build the exact life you want, you can prosper, you can become the person you want to be.

TLC: Yes. But in this work, there seems to be a question about that pursuit. Like we never really arrive at that destination, instead we stay in a continuous process of striving. Like, is there a happy ending there or is there never a “there” to get to?

ED: I totally agree. In the book, there are a lot of uniforms and costumes. And we also see people undressing, stripping away layers of cultural meaning. But, at the end of the day, I think there are things you can’t strip away—you can become aware of them, which is crucial—but you can never make them not exist. There is no self that exists outside of culture and the world.

TLC: But if part of the impetus of going through these kinds of experiences is that you don’t feel like you’re good enough as is, then as you go through them, if there’s not that full transformation, you’re still left with that same self that went into this in the first place or some version of that self.

ED: Right. The idea that you could just strip that away and there is some stable static truth underneath. I just don’t believe that, you know? Where do these ideas about ourselves come from? They come from interacting with the world. Internalizing it. There are certain things I remember my parents would say that have stayed with me, even though they probably forget about them within a day or two. Good and bad. And how do you parse that when you’re older, when you’re looking back, trying to think about why you made the decisions you made? I think a lot about that now that I am raising a kid.

TLC: Yes, I know you are a new dad. How does that life-changing transition to parenting inform this work? Pregnancy, babies, and children are a recurring theme but not shown with a typical parental gaze. In your pictures, there are models of fetuses, uncannily lifelike dolls, and one live baby that is being sized up with a measuring tape.

ED: I started making this work before Roman was born. But in the background was that question and expectation. Like “I’m getting to that age? Am I going to have kids? What if I don’t know?” There’s so much societal pressure surrounding the decision to have or not have kids, like it’s some kind of moral referendum on your essential character.

ED: And then there is so much performance. Like the holiday card. You look at a holiday card, everyone is smiling and happy and it creates a certain fantasy. Even if it seems anodyne, it creates a kind of pressure like “You have to have this. You have to want this. Your kids have to be perfect and happy and successful.” It creates an image to which you may conform or rebel against. The family portraits are essential to the project because they are these aspirational images that are completely constructed. But I’m not the one creating the performance. The performance is something that everyone knows and has internalized. They are saying, “This is how I want people to see me. This is how I want people to think of me and my family.” Where does that come from? It comes from seeing that image reproduced ad infinitum, right? Over and over and over again.

TLC: Exactly. And that social pressure to conform it all fits under that umbrella of self actualization. There is that notion that if you’re not a parent, are you really fully actualized as a human? Then it goes even further and that pressure and question is handed down to the kid. How do they measure up?

ED: Totally. There’s so much with kids where it’s like, oh, what percentile is your kid? Is your kid crawling? Are they walking? There are these standards that you feel like you or your child has to meet.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026

-

Jamel Shabazz: Prospect Park: Photographs of a Brooklyn Oasis, 1980 to 2025December 26th, 2025

-

Andrew Lichtenstein: This Short Life: Photojournalism as Resistance and ConcernDecember 21st, 2025