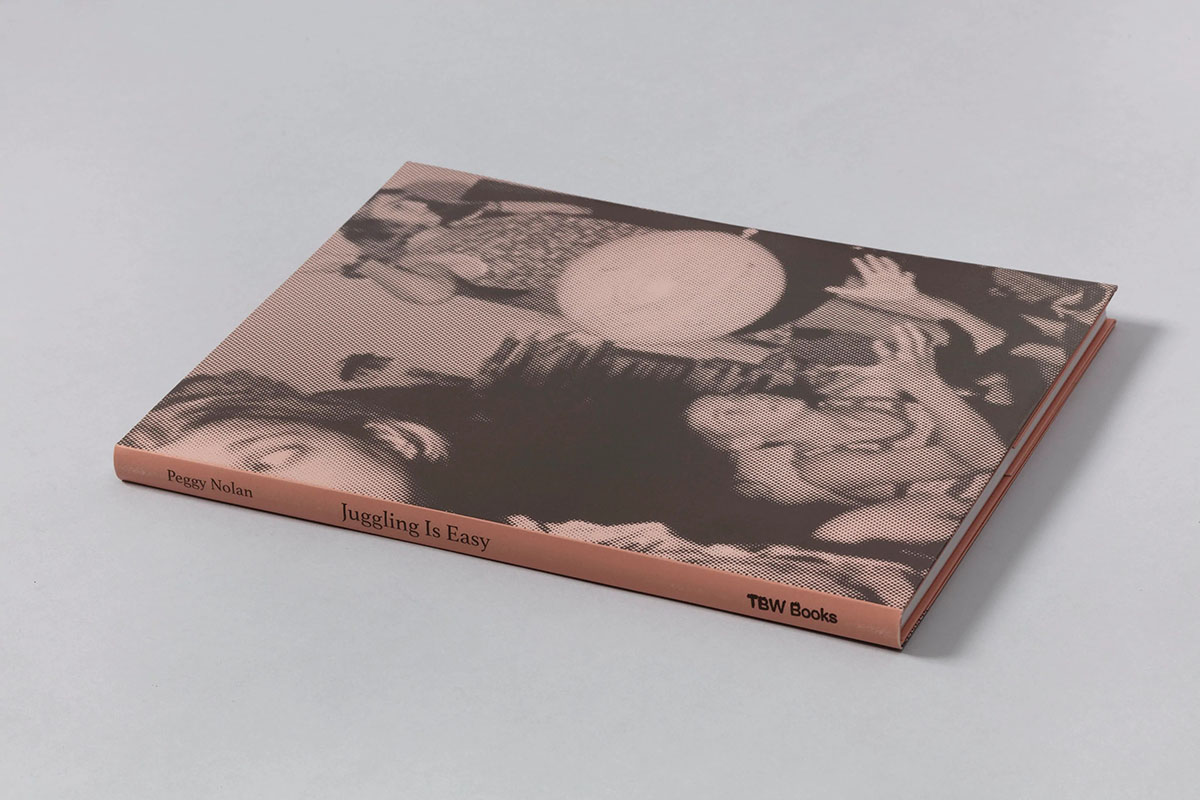

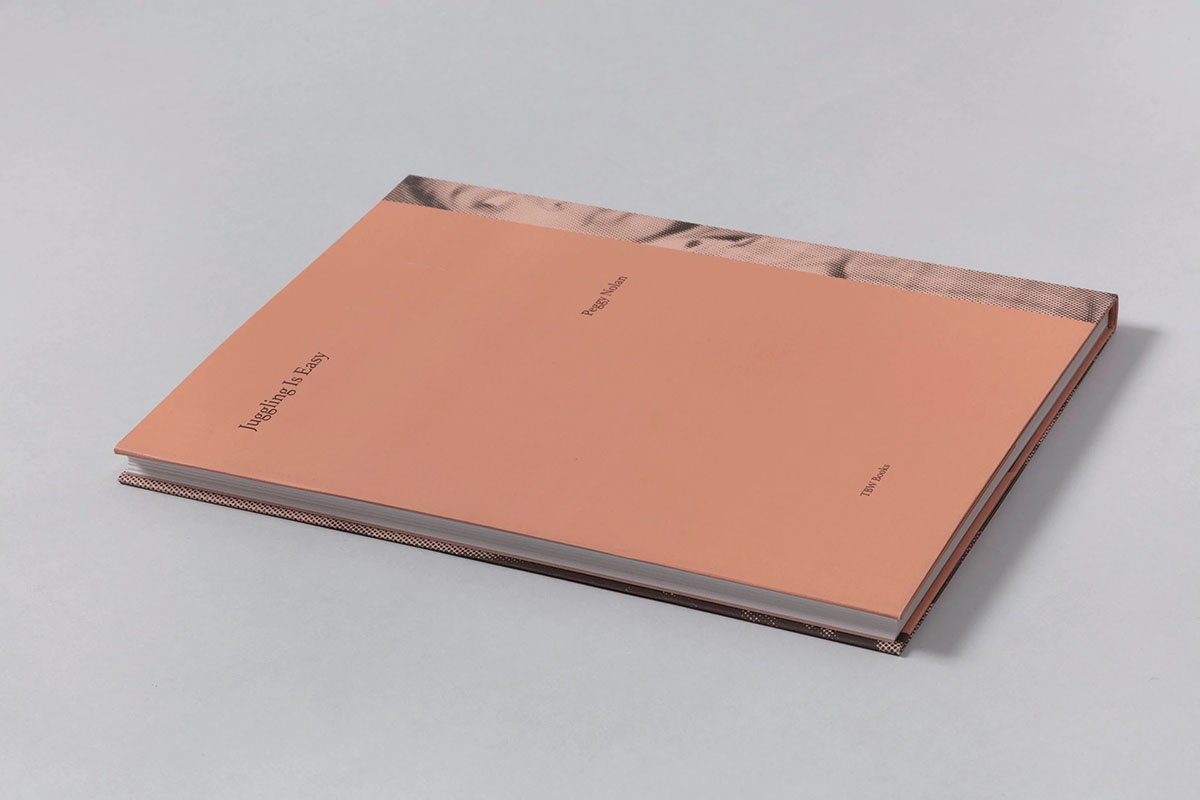

Peggy Nolan: Juggling is Easy

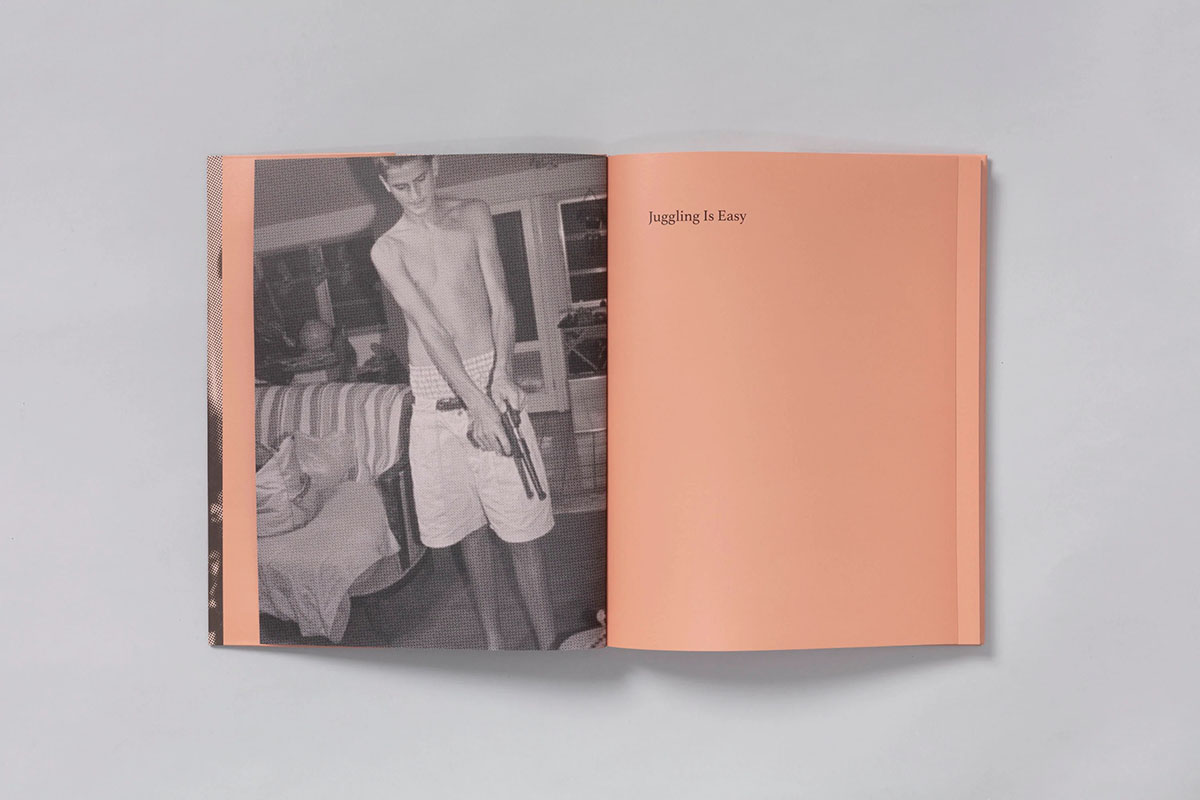

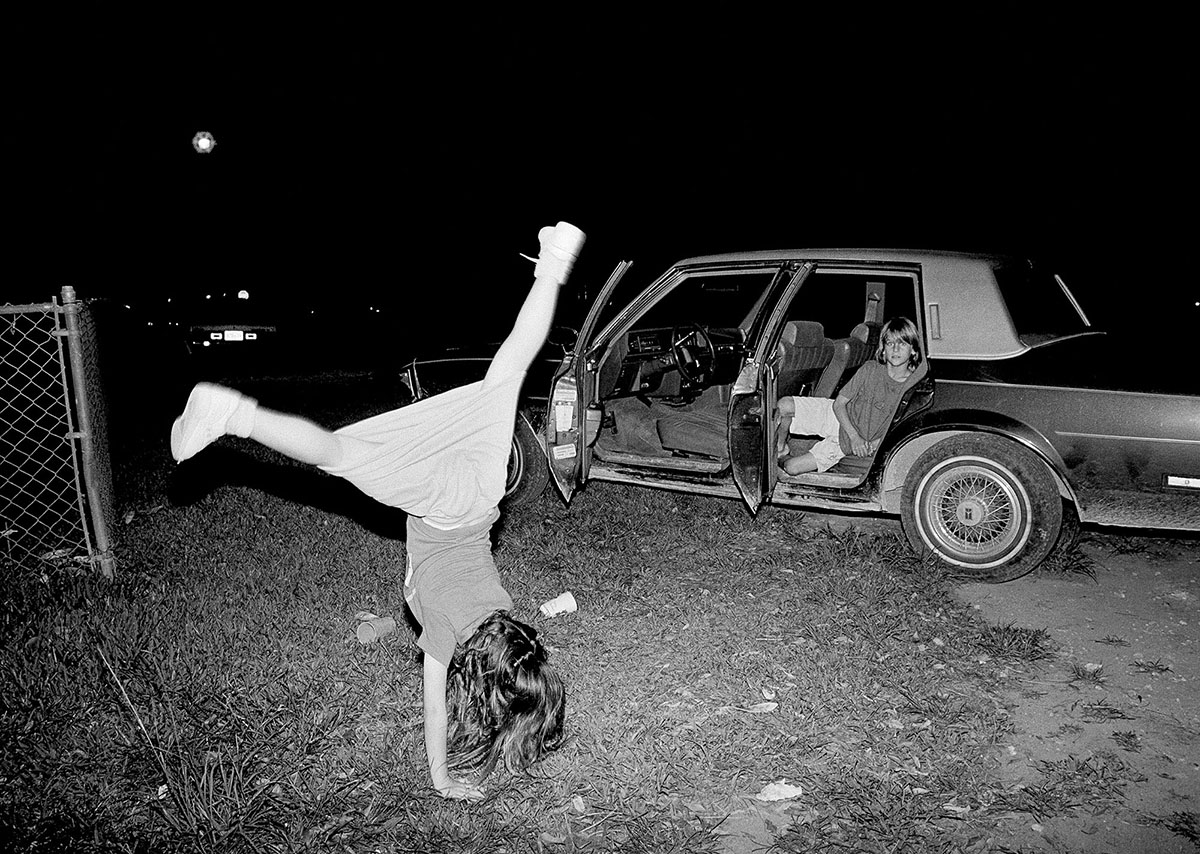

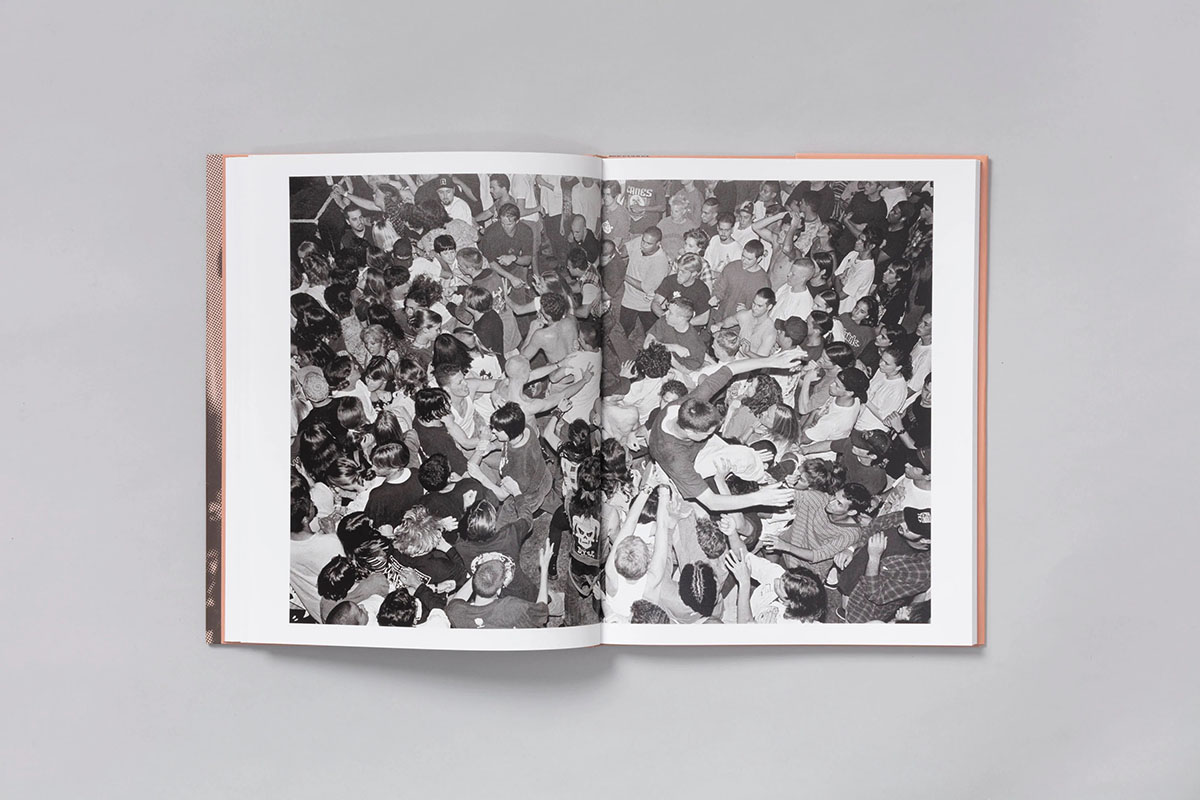

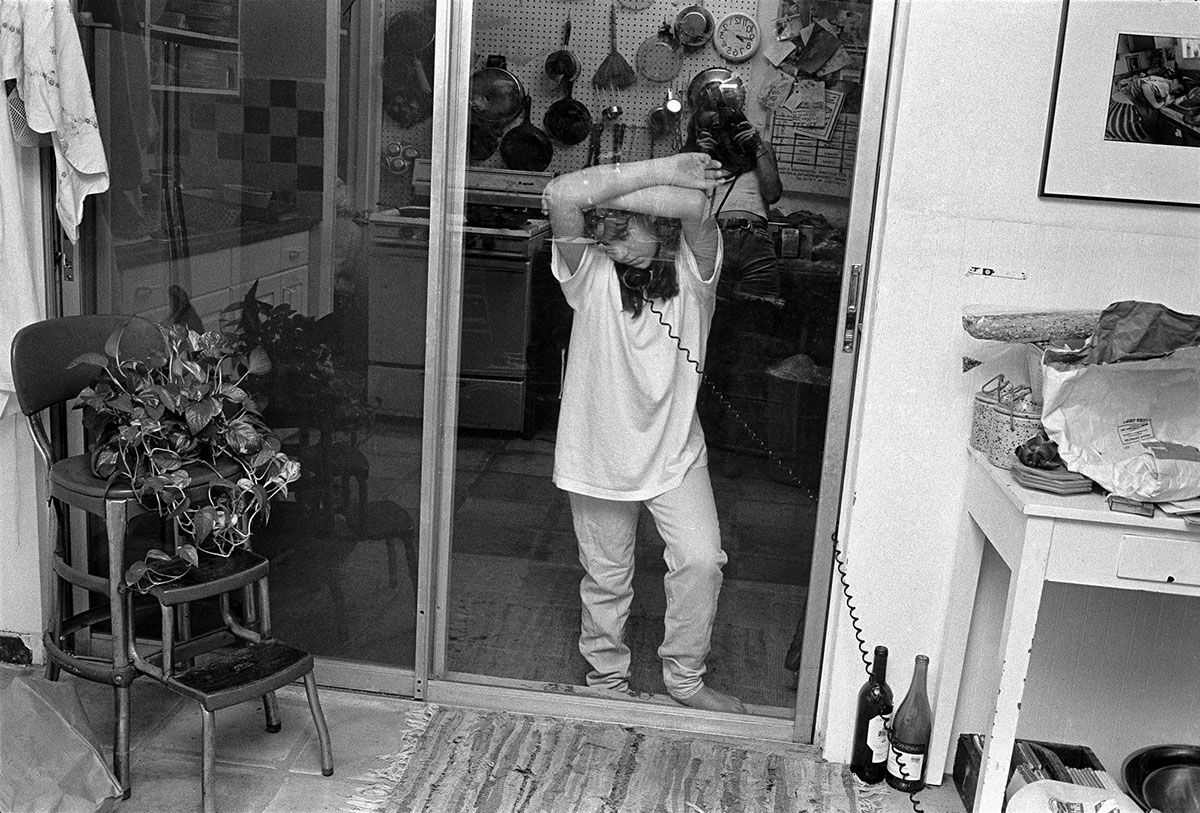

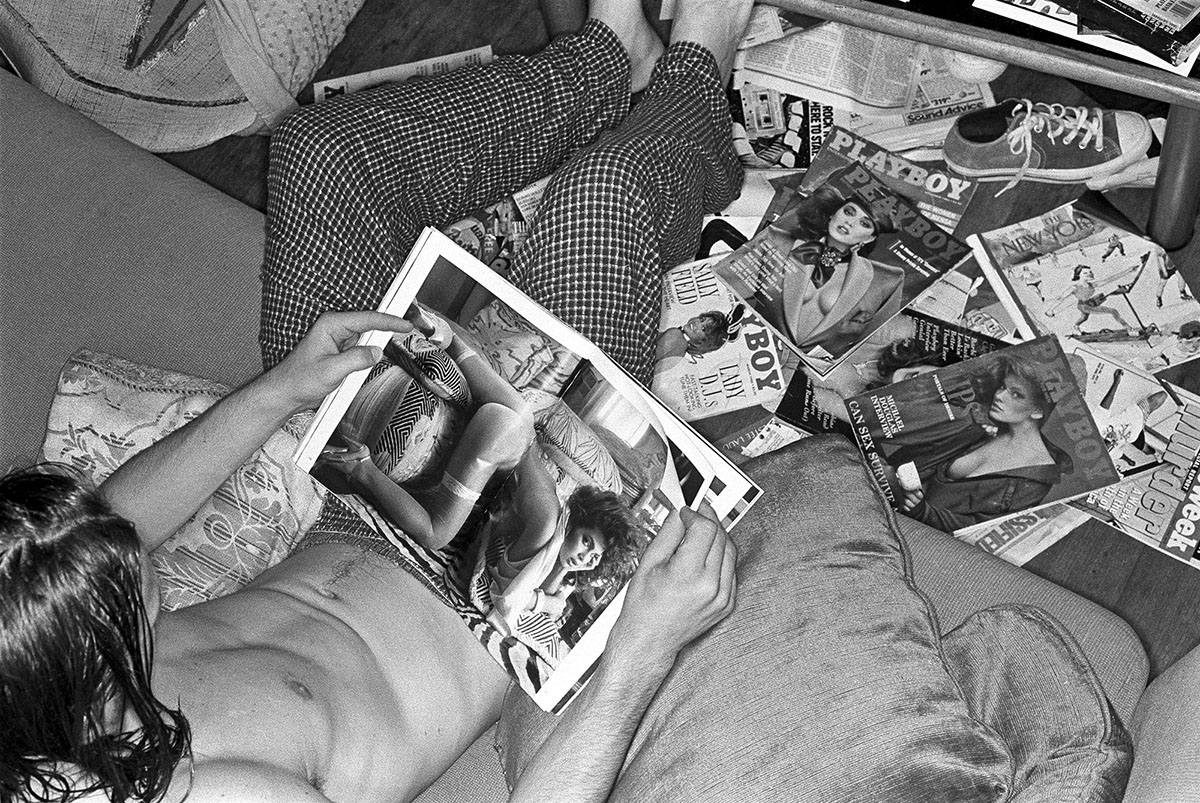

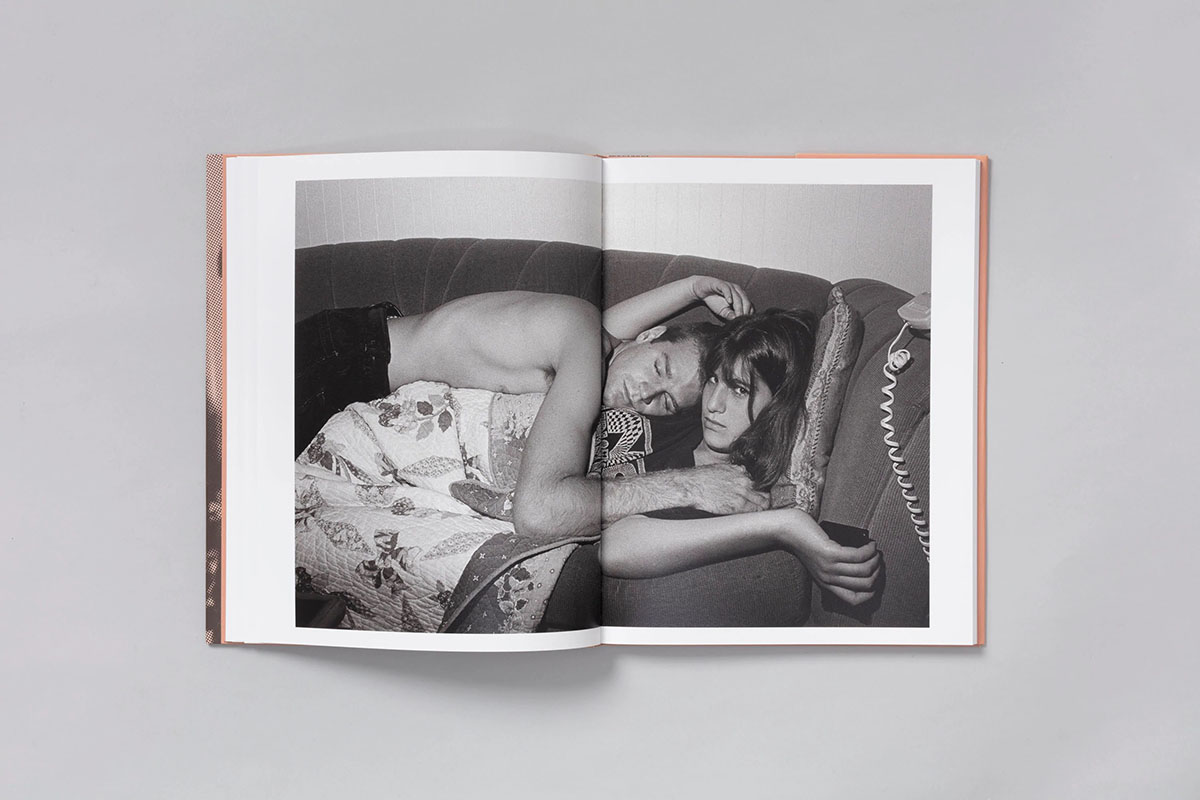

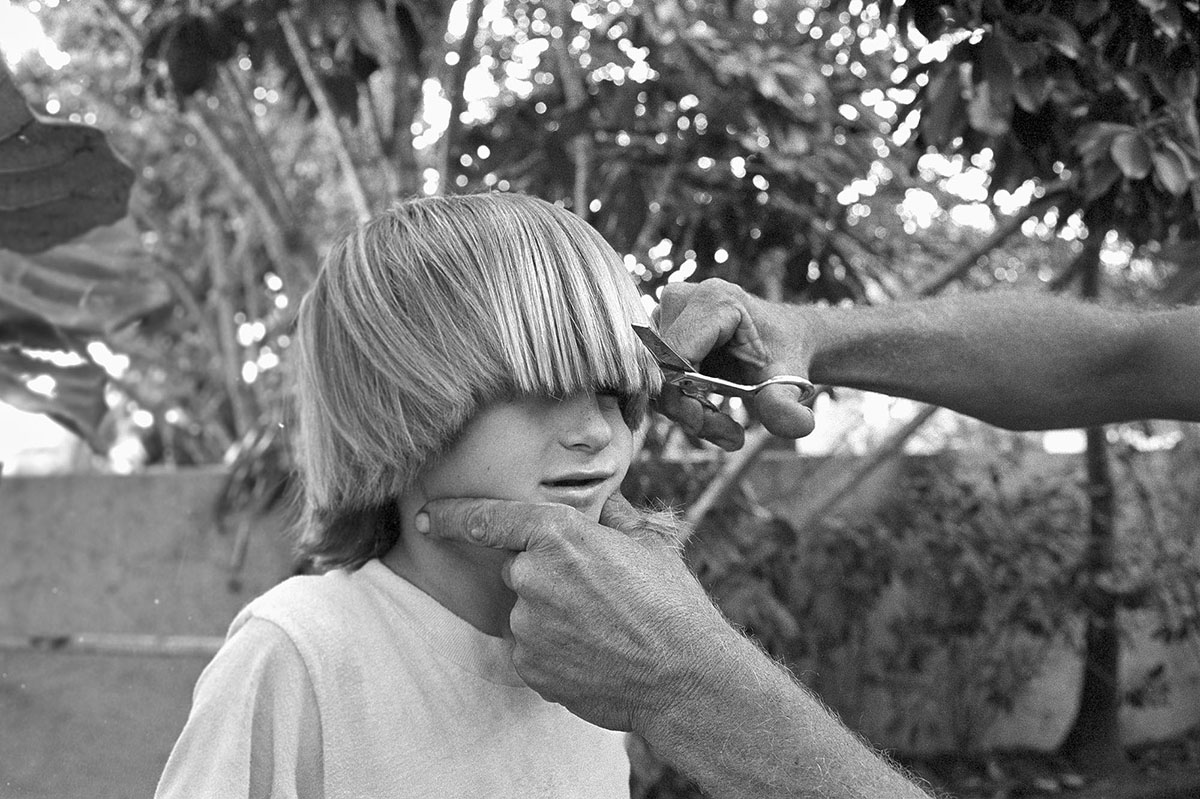

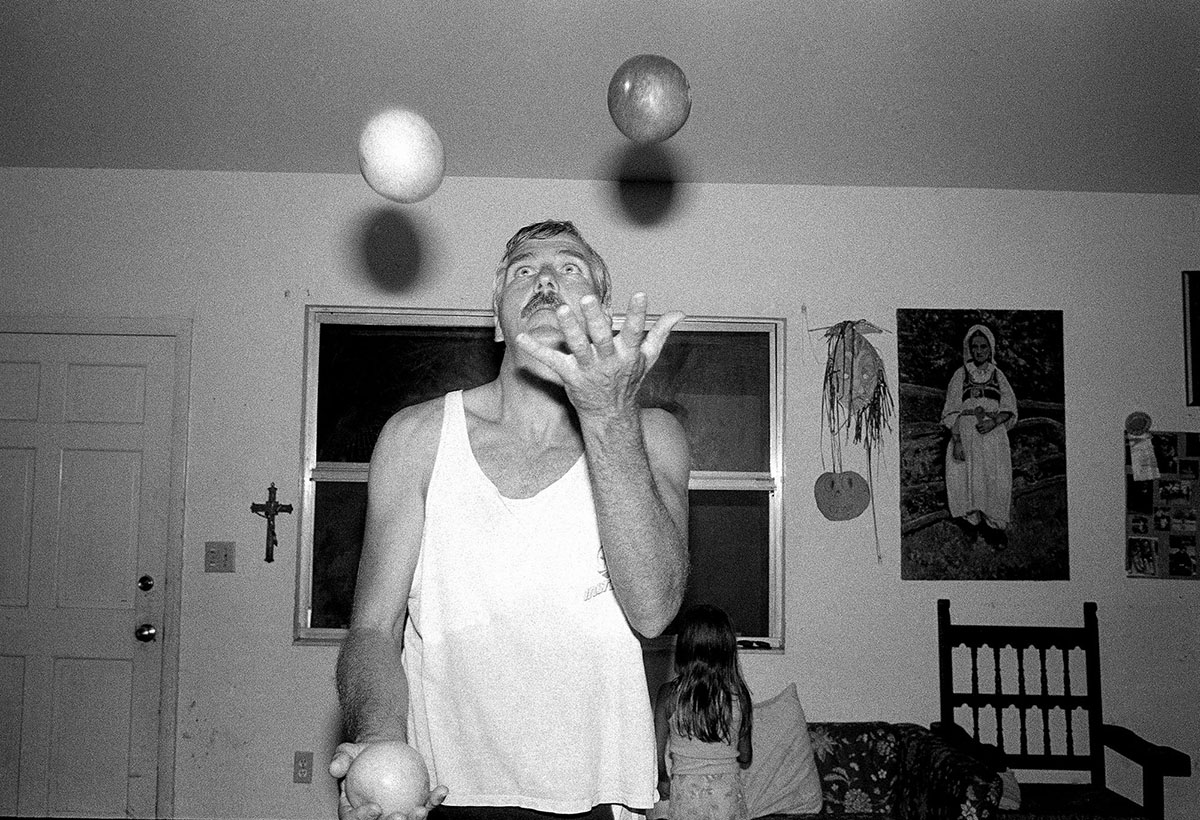

“Between 1967 and 1982, I gave birth to seven children. All are still alive and not a single tattoo.” And so starts off Peggy Nolan’s latest monograph, Juggling is Easy, published by TBW Books. The first image is of a teenage girl, safety pin piercing her nostril. She challenges the camera with a cold stare, a look that mothers everywhere will recognize. But many more images follow that would normally prove elusive for the parental gaze,… make-out sessions, stolen cigarettes, bridge jumping, and mosh pits. Many of us have lived these moments, but not with our mother and her Leica in tow. With this work, Peggy Nolan has afforded us access to her specific familial drama with all its universally recognizable rights of passage. What results is not your normal heirloom scrapbook but a photobook with a searingly intimate look at a complex family and a grounded revelation of the chaos of coming of age.

The following is a transcript of a conversation between Tracy L Chandler and Peggy Nolan.

Tracy L Chandler: I am so excited to talk to you about this work.

Peggy Nolan: Why? Because you lived it? I can tell by your age you lived this.

TLC: Yes. Because I lived it. The skateboarding. The mosh pits. Talking on a corded phone. I lived it, for sure. But I am also living it now from the other angle. I am a mother who makes photographs. And that’s a complex thing.

PN: Yes, it is. I have taught photography for a long time and I always encouraged my students to witness their own life. Don’t think of photography as an object. Witness, witness, witness.

TLC: Yes, but let’s talk about that witnessing as not just any participant observer, but as a mother. For some, the camera can serve as a tool to create distance and perspective. That can be illuminating but there is also deep conflict, at least for me, especially when I try to make “art” and agenda gets involved. What I want as an artist is to go for the jugular and expose something real and that is often in direct conflict with my instinct as a mother, to protect my child from vulnerability and objectification. That tension is there. My kid feels it. And he has his own ambivalence about wanting to be seen but also wanting privacy, autonomy, and control. Did you feel any of that conflict or tension when making this work?

PN: No. I wanted to make pictures and I knew that life would be the most interesting thing I could see. When they were in pictures, they were not my children. And I wasn’t thinking of myself as an artist when I made this work. That agenda wasn’t there. For me, I was driven by the fact that I didn’t have enough images of my brother and I growing up and I wanted my kids to know what it felt like to be them in pictures. And then as soon as I started making them, I realized that my pictures were different.

TLC: The pictures were different how?

PN: There was no conformity. (Peggy holds up a baby picture of herself.) You see this? It’s all tricked out with this white fade border. I was probably sitting somewhere in a studio, scared to death of the photographer. It’s different. My pictures have laundry piles in them.

TLC: There is a lot of expectation for photographs, especially around family portraits. Did your kids change their behavior when you were around with the camera?

PN: No. Not at all. I did it so much, they were bored with me. One of them said to me once, “Just be my mother.” But no they were just themselves. I encouraged them to be free in our household.

TLC: I can feel that freedom. And also connection. Literal connection. From tangled couch pile-ups to late-night make-out sessions to crowded mosh pits, people are touching one-another in almost every picture. And nothing feels shy or coy, it feels familiar in every sense of the word. Do you see photography as an extension of that physical connection?

PN: We were very physical as a family. I pushed two babies out at home. For a long time we didn’t have much money. Everybody slept on top of each other. We enjoyed that kind of physical closeness, it didn’t stress us out. In this work, there is a lot of attention to bodies and that’s also because of the age. It’s the age of strength and beauty and feeling like you’re never going to die.

TLC: Yes, you can feel that sense of invincibility. And even risk. There is a photograph of people literally jumping off of a bridge. How do your kids feel when they look at these pictures now? Do they relate to them as your work or do they relate to them as pictures of themselves?

PN: Both, but mostly as my work. They’re grown up and pretty far away from me now. As these pictures circulate their names are not necessarily associated. And most of the other people in the photographs are long dispersed. They’ve come and gone. But they like the pictures. They relate to them. On occasions we would get the stacks down from the shelf and go through them as a pastime when they were visiting. And there were stacks everywhere around the house as the kids were growing up. If you look closely they are in the background. I would come home from working in the darkroom and just throw the wet pictures on the couch.

TLC: So these do serve as a family album of sorts. Your kids have the pictures of themselves you didn’t have growing up. That makes me think about photographs and preservation of memory. I am very aware of my own subtle wish for photographs to somehow ward off loss. That if only I can capture this moment, this person, this feeling, I will be able to keep it forever. At the same time, I also know that is futile and that the photograph is only a proxy for the lived experience, and to go even further… the photograph can supplant the memory. But I still try. Was there a romantic notion in this for you? Were you trying to keep these moments alive forever?

PN: I really didn’t think about those things at all. I wasn’t trying to preserve memories. I don’t have that kind of wiring. It was making a picture about this moment. Because it looked good. Because the arrangement of everything in the frame was kick-ass. Instant gratification. I don’t have the sappy side. It has very little to do with the wonderful people that are in the pictures.

TLC: There is so much action throughout this work. Skateboarding, wrestling, trampolines, and cartwheels. I can imagine 7 kids would involve non-stop action. I am wondering how you are able to keep up.

PN: Coffee, it’s coffee. Well, did you see the picture of Abner laying on top of clean laundry? I didn’t keep up. That’s like thousands of pounds of clean laundry that never got folded.

TLC: That’s interesting because that is an example of punctuated stillness. They are like rests between all the action.

PN: You know, it was very hard when they all moved out. There was no more action. Nothing to photograph. Generating ideas is not my thing. The only subject that I’ve ever really cared about is my own gene pool. I call it work of consequence. Some people do care about that other stuff. I shot a lot of weddings and I did care, but I didn’t care about the wedding. I cared about getting into somebody’s personal business. I cared about a day full of tension.

TLC: Can we talk about how this came together in book form?

PN: I’m addicted to photobooks. I have a shelf in my living room that is ceiling to floor with photobooks. Most of them I bought to show my students. I would keep them in the classroom so at any time I could pull a book off of the shelf and say, “This is how it’s done.” The final for each class was to make a book. They could sew it together, they could staple it together, they could go to Office Depot and do the ring binder, I didn’t care. But they had to understand how their pictures worked in a book. And, you know, that’s all I wanted out of my own work. But I had less confidence until now.

TLC: Were you waiting for a certain amount of time to pass?

PN: I didn’t plan it that way. I really didn’t. This is an accidental success. My son lives in San Francisco and knows Paul (Schiek of TBW Books). I was going to visit SF and he told me to bring the work and let’s show it to Paul. I had cut it down to about 190 pictures. I knew it was good. I didn’t need anybody to tell me that, but I want to know how they felt about the edit. Well, I showed it to Paul and he said this has got to be a book. And he worked on an edit. Down to 70 or 80 pictures. It’s tight and edgy and different from what I would have done. In Paul’s hands, it got much, much, much better.

Juggling is Easy by Peggy Nolan is published by TBW Books and includes an essay by Rebecca Bengal. The photobook is available for purchase through TBW Book’s website.

Peggy Nolan is a photographer based in Hollywood, FL.

Follow Peggy Nolan on Instagram

TBW Books is an independent photography book publishing company founded in 2006 by Paul Schiek.

Follow TBW Books on Instagram

Tracy L Chandler is a photographer based in Los Angeles, CA.

Follow Tracy L Chandler on Instagram

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026