Refracting Histories at the Museum of Contemporary Photography

Refracting Histories features eight artists looking critically at the traditional canon within the history of photography. Each artist challenges, probes, or deconstructs well-known art historical legacies, revealing the contributions of overlooked makers as well as pervasive discrimination that maintains the status quo. While some artists appropriate well-known works into new forms, others set up a constructed environment to visualize lost histories. Collectively, the exhibition honors the malleable nature of photography as a fitting medium to redirect, reinterpret, and expand upon prescribed doctrines.

Photography depends on the refraction—or bending—of light waves as they pass through the lens. As the artists in this exhibition change the direction of how we look at art history, they reveal multilayered, often misplaced stories that exist alongside more dominant narratives. Their works prove to us that there are limitless stories to discover, once they are moved from the shadows of hierarchies and into the light.

Exhibiting artists include Tarrah Krajnak, Aaron Turner, Sonja Thomsen, Colleen Keihm, Tom Jones, Nona Faustine, Kelli Connell and Natalie Krick.On view at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago until April 2, 2023.

An education guide to the exhibition is available.

A curatorial tour can be found below:

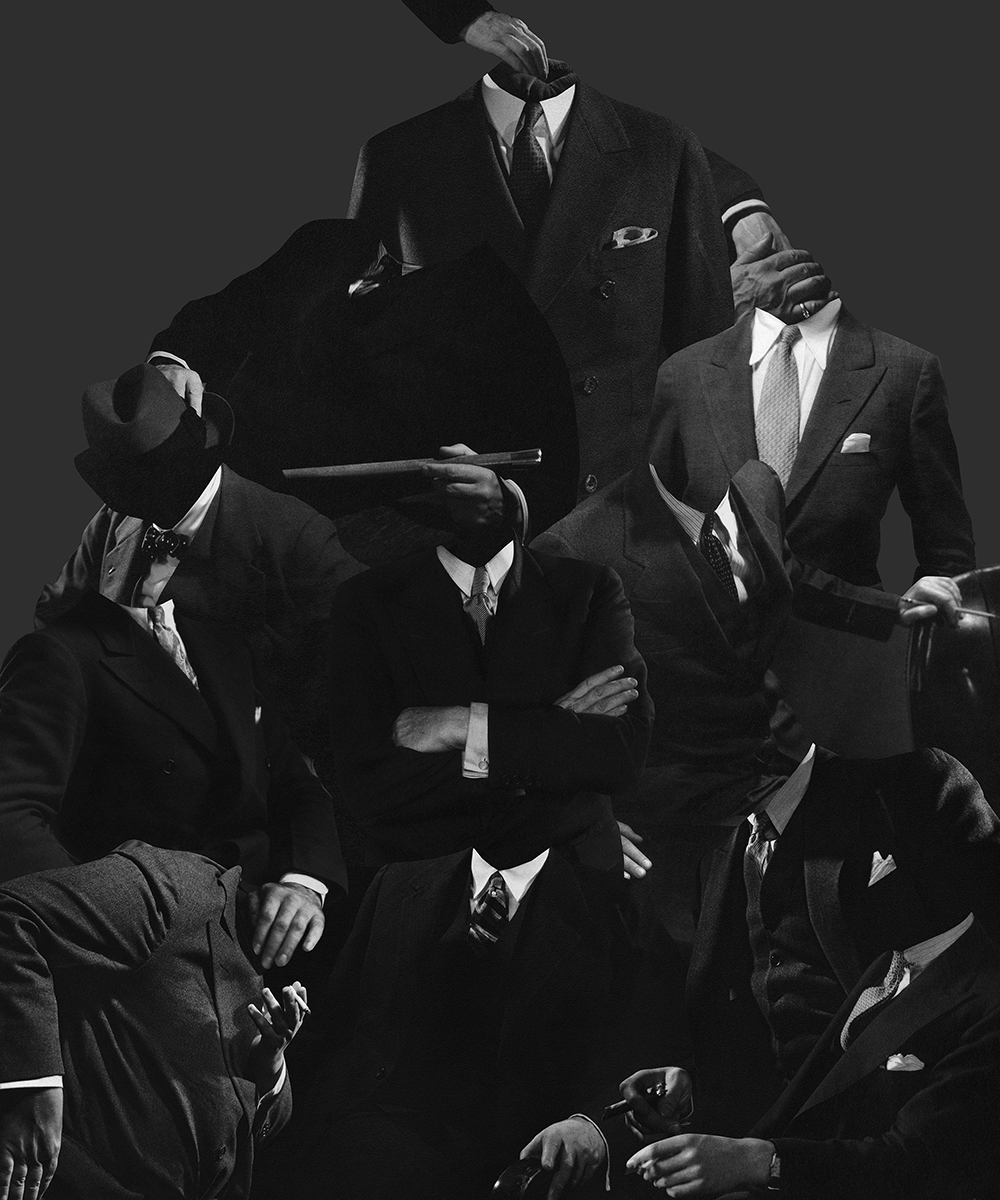

Kelli Connell and Natalie Krick consider the often-uncontested views regarding the so-called photographic masters by placing a contemporary feminist lens on the work of Edward Steichen (1879–1973) and his position as the curator of the famous exhibition The Family of Man, presented in 1955 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA). By appropriating and remixing works that Steichen selected to represent the state of humanity during the mid-twentieth century, Connell and Krick bring Steichen’s work into a current dialogue about power, with a humor at once whimsical and deliberate. They also weave in some of Steichen’s commercial fashion work, which further examines the roles of white women in post–World War II. In this exhibition, they specifically highlight the longevity of issues like war and climate change that were represented in The Family of Man, as a meditation on toxic masculinity and ongoing destruction caused by conquests.

The title for the project, o_Man!, and the text panels throughout their installation employ techniques typically seen in redacted poetry. By removing words from original text passages found in The Family of Man catalogue, Connell and Krick isolate and emphasize recurring language that, viewed with a 2022 sensibility, seems explicitly gendered. One text passage reads, “all things relative,” reminding us that what we teach about our histories is not objective, and what we know about the history of art is often traceable to critics who deemed certain works or artists more intrinsically valuable than others.

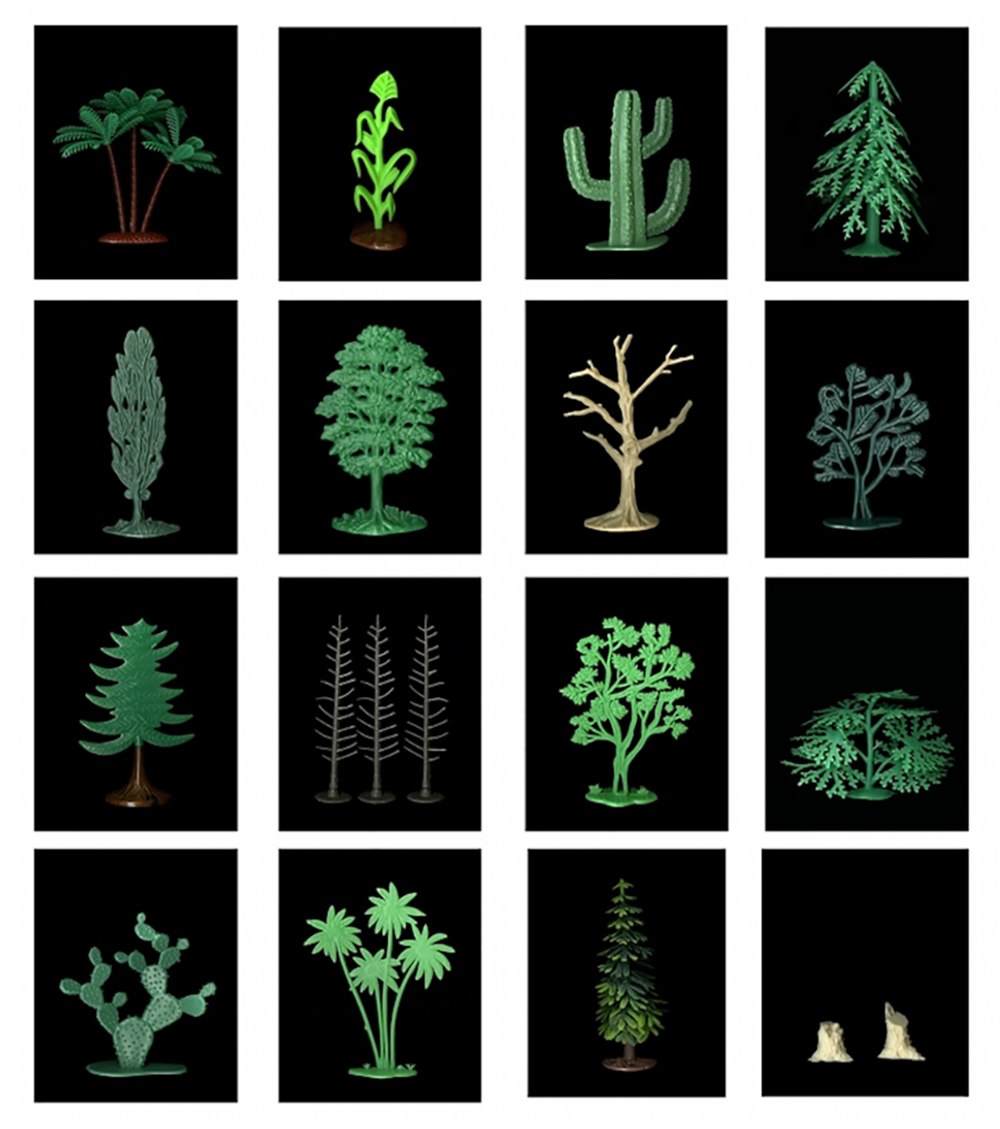

Tom Jones also reimagines a photographic icon, Edward Curtis (1868–1952), by riffing on Curtis’s romanticized portrayals of Indigenous populations. Jones is interested in how Indigenous people have been portrayed not only in photography, but also more broadly in visual culture, and creates works that counter reductive representations of places and people. In his North American Landscape series, Jones satirically interprets images from Curtis’s iconic North American Indian book of 1907. Funded by industrialist J. P. Morgan and with a foreword by Theodore Roosevelt, Curtis portrayed a stylized version of the historic Native American rather than the actual people he encountered, and in so doing he downplayed the contemporary aspects of their lives. Jones’s images, rather playfully, feature plastic toys that match trees found in the backgrounds of Curtis’s images. Each image is titled with the name of the tribe belonging to the region where a specific tree grows, revealing the many Indigenous groups and identities that have been flattened into one idea of “Indian-ness” over time.

Like A Pregnant Corpse The Ship Expelled Her Into The Patriarch from the White Shoes series. ©Nona Faustine

Nona Faustine also considers how photographs shape larger narratives and notions of representation. In her project White Shoes (2012–2021), she makes self-portraits in locations around New York that have undertaught—or untaught—histories of enslavement. In Venus of Vlack Bos (2012), Faustine refers specifically to a group of daguerreotypes that were believed to be the first photographs of enslaved people, made in 1850 by Harvard-appointed biologist Louis Agassiz. Agassiz created nude images of two individuals, without their consent, to support his botched theory of racial hierarchy. In Faustine’s image, the artist wears only her signature white shoes, white gloves, and a tiara and confronts the viewer with her gaze to claim her ownership of the portrait. The title additionally refers to Sarah Baartman, a Khoikhoi woman who was condescendingly referred to as “Hottentot Venus,” as her body was exoticized and put on display by European colonizers in the eighteenth century. The white of Faustine’s accessories pulls our attention to her feet and crown and represents whitewashed patriarchal histories, while the careful placement of objects asserts her place in reclaiming the care denied her ancestors.

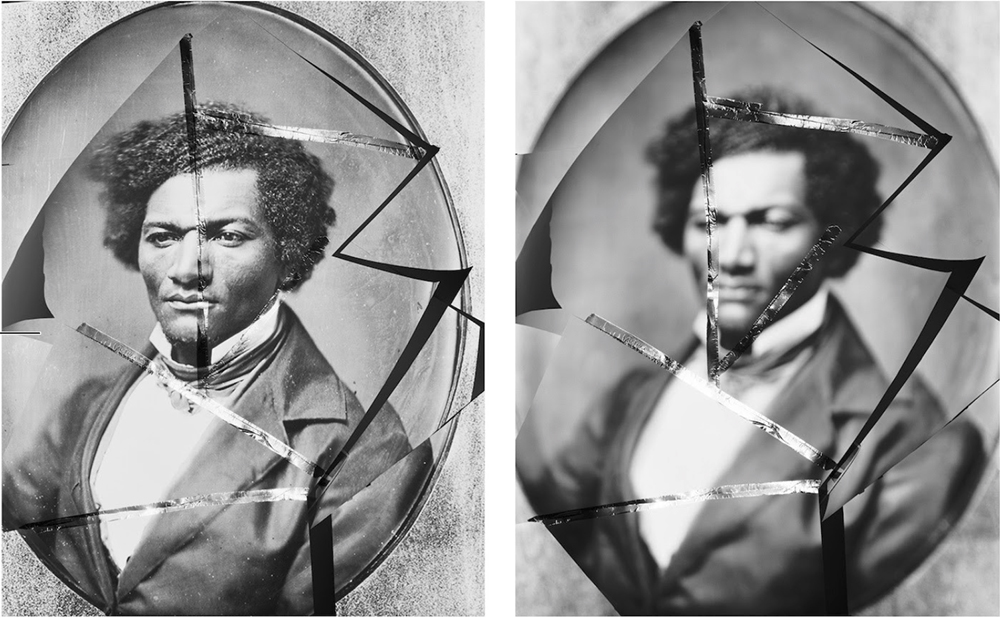

Aaron Turner presents multiple photographic translations of the most photographed man of the nineteenth century, US abolitionist and statesman Frederick Douglass (1818–1895). One of the first critical theorists of photography, Douglass delivered a lecture titled “Pictures and Progress” in 1861, in which he pointed out photography’s potential to destroy stereotypes and empower through self-representation: “Men of all conditions may see themselves as others see them…The humblest servant girl, whose income is but a few shillings per week, may now possess a more perfect likeness of herself than noble ladies and even royalty.” Understanding the power of photography to shape stories, it is no surprise that Douglass took to putting himself in the frame, posed and clothed in the manner of his own choosing. In taking Douglass’s iconic portrait, fracturing it, and then translating it with various photographic techniques from the nineteenth to the twenty-first centuries, Turner reflects on Douglass’s under-recognized and prescient views on the photographic image. Turner’s series features mediums ranging from cyanotype to a daguerreotype. Fittingly called Seen of light and legacy, his project is a nod to the magical qualities of light in photographic processes, while it points to a persistently troublesome history of representation through the decades.

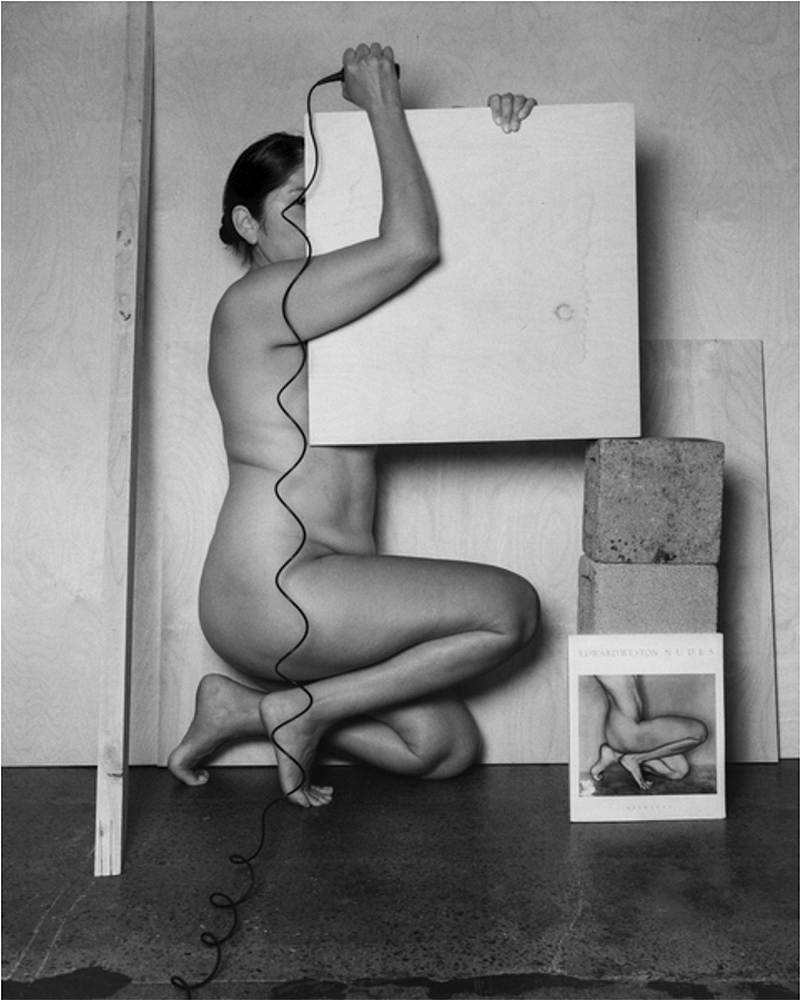

Self-Portrait as Weston/as Bertha Wardell, 1927/2020, from Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes, 2020. ©Tarrah Krajnak

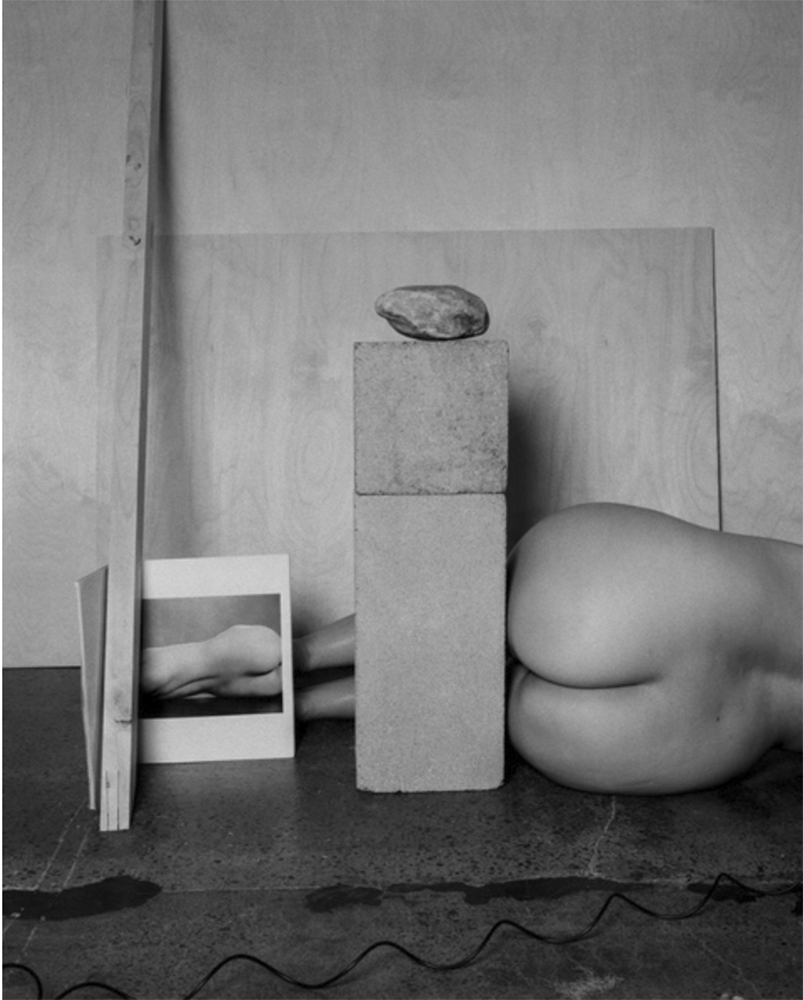

Self-Portrait as Weston/as Miriam Lerner, 1925/2020, from Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes, 2020. ©Tarrah Krajnak

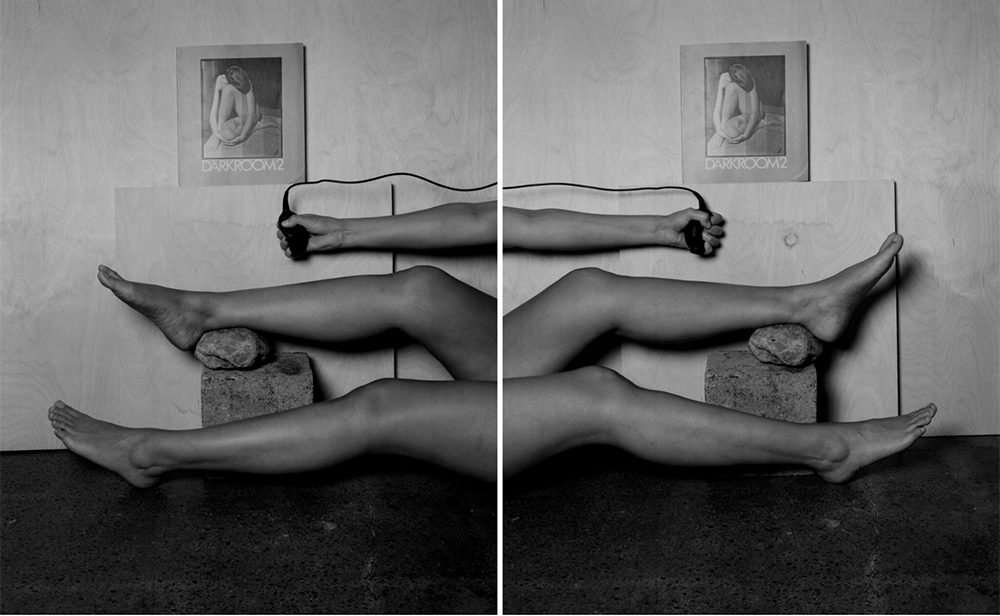

Tarrah Krajnak similarly looks at under-recognized contributions to the field, using her body to re-create works by Edward Weston (1886–1958) that portray Weston’s muses Bertha Wardell (1896–1974), Miriam Lerner (1896–1976), and Charis Wilson (1914–2009). Krajnak amplifies the creative role Weston’s models played in the images and claims authorship of one of the most repeated and reductive tropes in photography: the female nude. By revealing the camera shutter release in hand, Krajnak asserts herself as the maker of the image while also serving as the model, a strategy emphasized by her titling of the photographs As Charis Wilson/As Edward Weston (1934/2020) and As Bertha Wardell/As Edward Weston (1927/2020). In addition, she expands Weston’s frame to include wooden panels, cinder blocks, and book pages that include Weston’s photographs, her source images. The wooden panels sometimes indicate where Weston cropped his images, often eliminating the heads of his models and voiding their identities. In the dual act of expanding the frame and giving ownership to the model, Krajnak asks us to consider who has helped people achieve fame and recognition in this field—and what is left out of this process of adoration.

Like Krajnak, Sonja Thomsen pays tribute to a less well-known partner of a much more famous man. Thomsen created Orbiting Lucia (2022), a site-specific installation in tribute to Lucia Moholy (1894–1989), who was once the wife of painter and Bauhaus educator László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946). Moholy was a prolific artist, teacher, and writer who frequently collaborated with her husband on camera-less photography in the Bauhaus darkroom and documented the people and architectural spaces of the school. Despite her many contributions, Moholy was often overshadowed by her male peers, including her husband. Her most notable absence was her mostly unrecognized co-authorship of the 1925 book Malerei, Photografie, Film (Painting, Photography, Film), which is credited to Moholy-Nagy alone as one of his greatest works. Similarly, when Moholy was forced to flee Germany due to the war she left behind her collection of 560 glass-plate negatives, and when she later asked Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius (Germany, 1883–1969) for their return, he refused. In fact, Gropius used them to print forty-nine photographs for a 1938 publication for an exhibition about the Bauhaus at MoMA as well as in marketing materials that helped build the image of the institution, without citing Moholy as the photographer. Only after a lawsuit did she regain ownership of the work.

Thomsen works with reproductions of Moholy’s photographs, cropping sections to emphasize imagery of hands across different generations to underscore unacknowledged labor and care provided by women. Celebrating Moholy’s creative output by interfacing with fragments of Moholy’s legacy, Thomsen created her own photograms inspired by Moholy’s early experiments. She then placed the images within varying levels of light, which fluctuate in the installation depending on where one stands. Looking up, a mobile titled and manner of our collaboration (2022) recalls an apostrophe, the punctuation of possession. In the video, titled still feel the process of their formation reverberate in my mind (2022), text moves in and out of focus, as audio portions of Lucia Moholy’s 1972 essay “Marginal Notes: Documentary Absurdities” are read both in German and English. As the audio becomes indecipherable and without translation in real time, one is challenged to deduce the meaning of the text. In this way, Thomsen invites us to reconstruct Moholy’s legacy and to question.

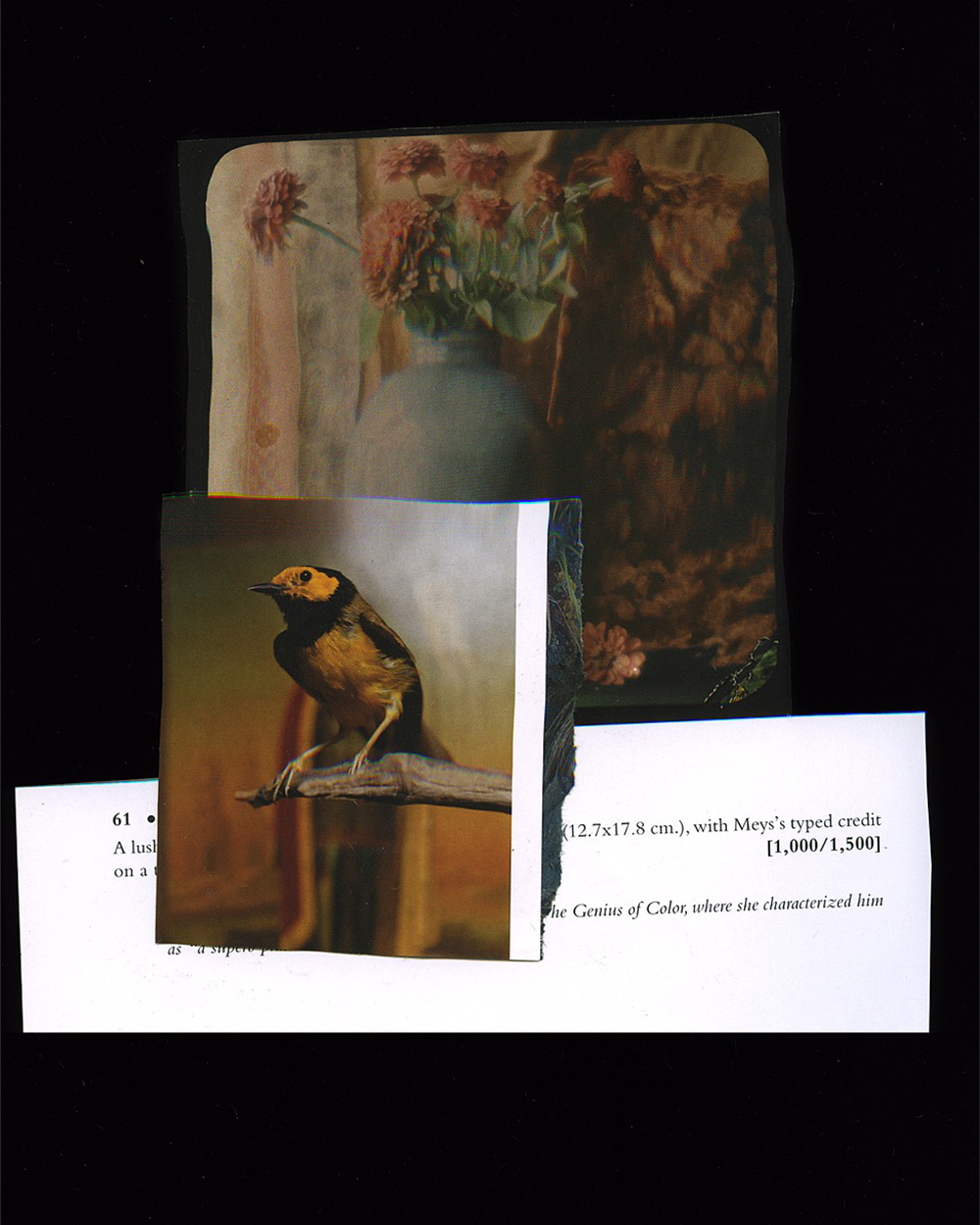

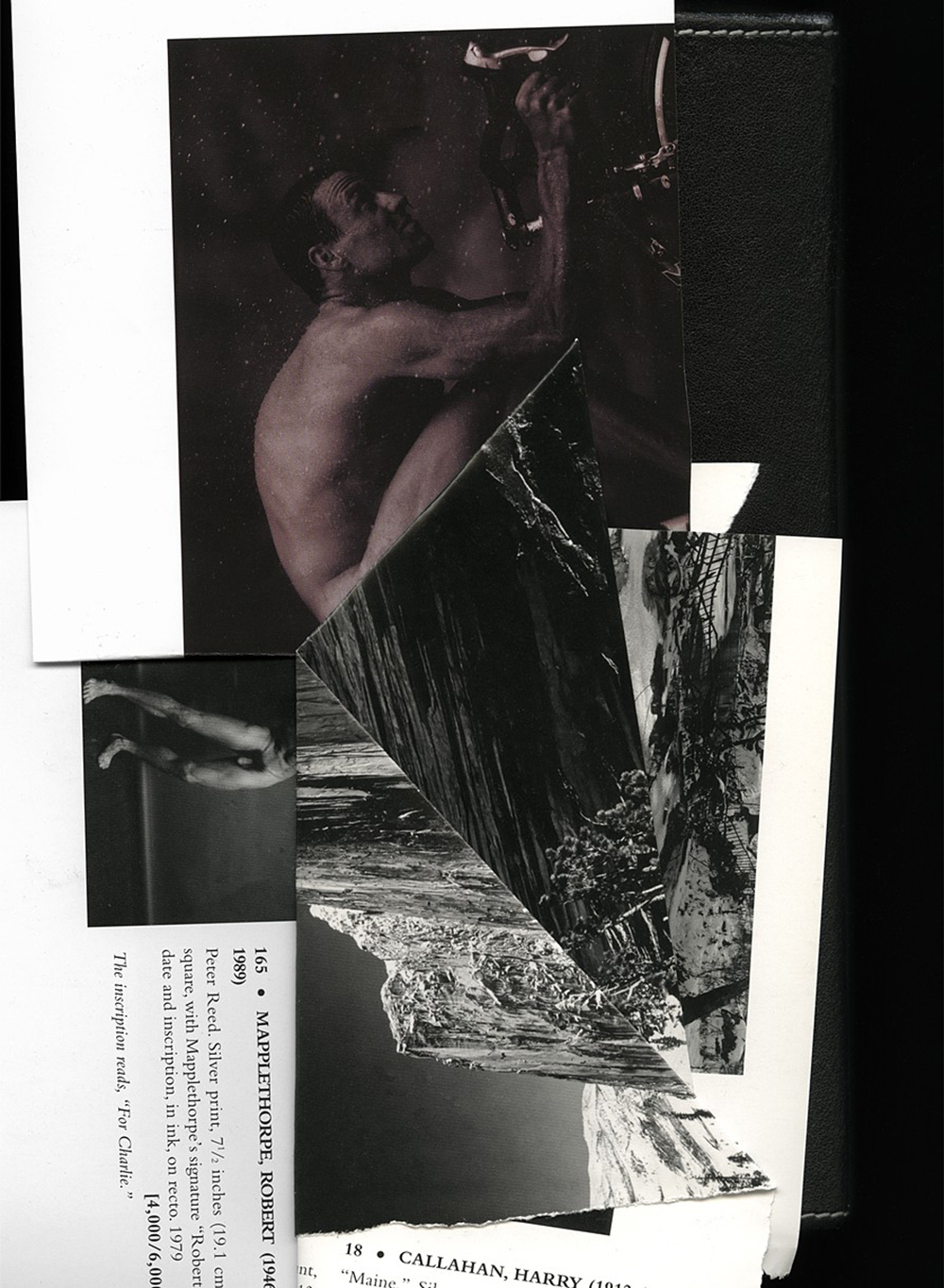

In her project Becoming so familiar that it’s you (2020), Colleen Keihm collages fragments of auction catalogues to look critically at the values placed on some artists over others, and how the market of collecting correlates with the narrow teachings of art history textbooks. Thinking of new possibilities of radical inclusion, her practice disrupts depictions of traditionally celebrated authors by overlaying details from other images in the catalogues that portray calm moments in nature. Keihm uses dreamlike imagery of horses, birds, and historical photographs next to iconic works to escape conventions of good or bad, hinting toward the possibility of a more equitable and democratic art historical narrative.

Karen Irvine and Kristin Taylor curated Refracting Histories for the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago where Irvine is Chief Curator and Deputy Director, and Taylor is Curator of Academic Programs and Collections.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026