Robert Lyons: Zero Line Boundary published by Zatara Press

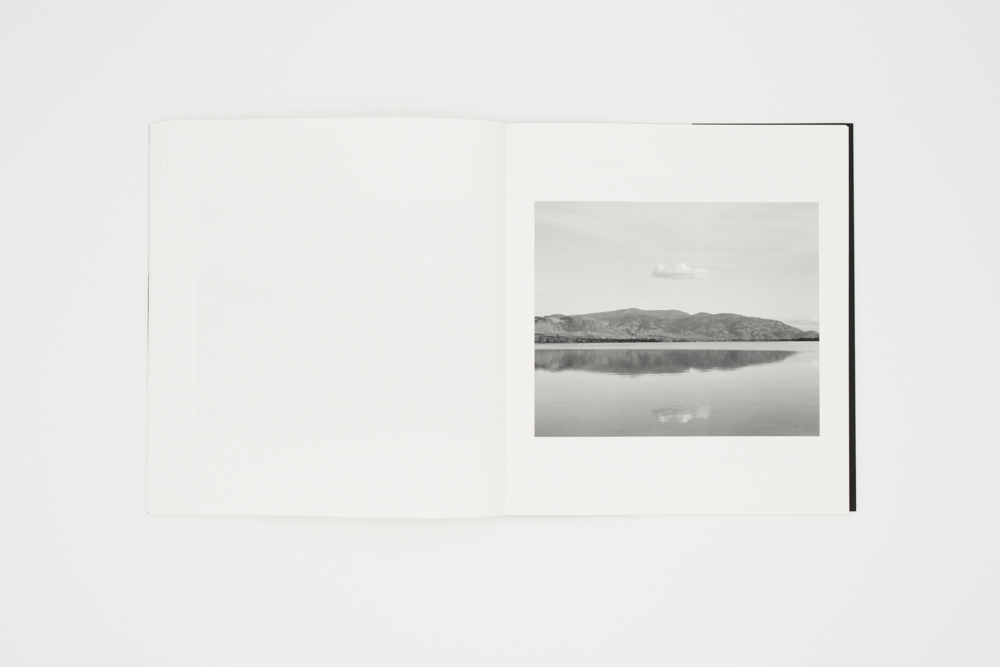

Robert Lyon’s latest monograph, Zero Line Boundary, with Zatara Press, focuses on the dividing line between Canada and the United States. This Northern Border, which is the world’s longest continuous border, is often overlooked in American culture and media, at least when compared to the highly politicized and walled border to our south. Photographing along this quiet, open, and seemingly undefended boundary, Robert Lyons uses black-and-white photographs of the area and its inhabitants to explore themes of nationhood, territory, and surveillance. Weaving together portrait and landscape photographs with thoughtful design, Zero Line Boundary assembles a quiet but complex sequence of metaphor and direct observation. Beyond his photography practice, Robert Lyons also serves as an educator and is the founding director of the Hartford Art School’s Photography MFA program. In full disclosure, he was my grad school advisor and it was nice to talk with him about his work for a change.

The following is a transcript of a conversation between myself, Tracy L Chandler, and Robert Lyons.

Tracy L Chandler: The title of this work is Zero Line Boundary. I understand this is referencing the seemingly permeable border between Canada and the United States. This is interesting because you are making pictures of a border, which, in its essence, is not physical. It is an abstract concept, a reference point. There’s not a thing there to photograph.

Robert Lyons: Exactly. There’s not a thing there. It’s a construction, an agreement that symbolically resides on the 49th parallel. And the Southern Border is also a concept except that for some reason Americans feel like we should erect an actual physical wall. The Southern Border is always noted for illegal immigration and drug trafficking. But it turns out that plenty of drugs and humans are crossing the Northern border. I was curious about this. Why is it that the Northern Border is seemingly quiet in the media? This was one of the many questions that were swirling when I started to photograph this area.

TLC: Can you tell us about how you went about making these photographs? Were you solely photographing in the US or crossing into Canada as well?

RL: Both. And in all cases, I crossed over at legal crossings because if you don’t, you’re subject to jail time. If you step over the physical border, they see you. For example, I was photographing an apple farm in Oroville, Washington. It is right on the border and I had permission from the farmer to be on his property. Afterwards, I visited the Homeland Security building to let them know I would be photographing at other locations in the area. The agent I spoke with said “Yeah, we know. We have been watching you the entire time.” They have surveillance cameras, motion detectors, and drones.

TLC: Creepy. The surveillance state is real. What did you find as you traversed this boundary? Zero Line

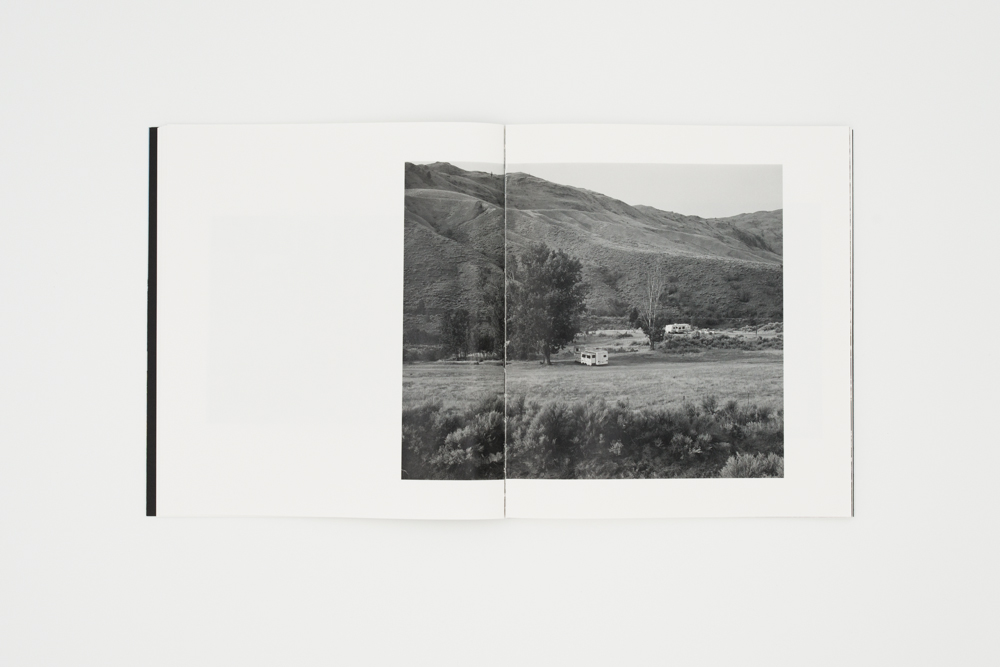

RL: It’s a beautiful landscape and there are both obvious and subtle differences between the two different sides. In British Columbia property is very expensive. People are owning houses that are worth two or three million Canadian dollars in these very suburban neighborhoods. On the US side, it’s much more rural and low income. People who live there don’t want to be bothered. A lot of people go to the border to disappear.

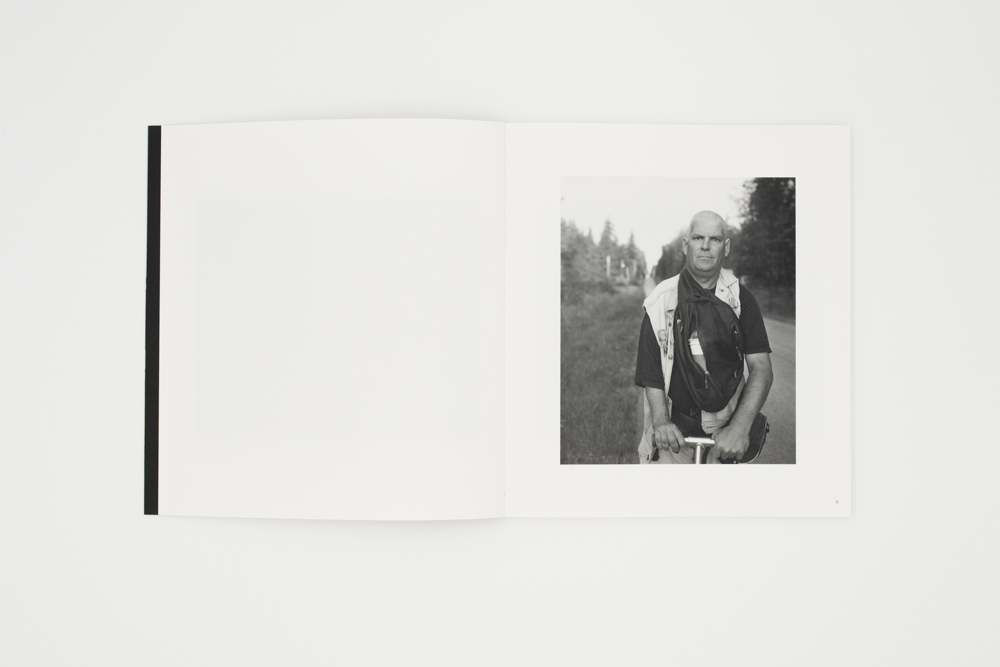

TLC: There are certain pictures that are pointing to that discrepancy. There are pictures of orderly McMansions as well as pictures of open fields strewn with detritus. You also photographed the inhabitants. As I view the portraits, I feel a certain level of conflict or reticence. The subjects are engaging you as the photographer, their eyes to the camera, yet there is often a “tell”, their arms crossed, their chin turned, or their glance askew. There’s even one where a child is clinging to her mother, showing a certain level of distrust.

RL: Yes. I found in Washington State where that specific portrait was made, people at the border were living there to be left alone and had little interest in outsiders. Often I would revisit the same locations and look for the subjects to share the photographs we had made together. In so many cases, the people had disappeared, moved on.

TLC: Interesting. I can feel that sense of transience in some of the portraits. You are not showing the inhabitants within a home, but more moving through, mostly depicting encounters along a sidewalk or roadway. One of the first photographs in the book is of the road surface itself. On one side the asphalt is smooth and the other side it is more rough with a patchwork of pavings. This is so graphic in form and reminds me of a map with lines and boundaries. What is going on in this picture?

RL: So this photograph of the broken road shows the border line itself running right through Native American land. On the Canadian side, it’s awful. And on the US side, the road is kept better. In other places it’s the opposite. This is just another physical example of these subtle shifts from side to side.

TLC: There is another surface picture, a plywood material stretching across the entire image. It is blocking us from seeing anything but its surface. It is literally making a wall. How does that relate to these other images where the border seems so open with only signs referencing that there is even a boundary there?

RL: With these boundary posts, you look on one side, it says America, the other side, it says Canada. And actually, in many areas, there is a “no-man’s-land” in between. A space where you are not in either country or maybe you are in both. It is all a continuation of these arbitrary constructs.

TLC: And these signs that you photograph, street signs and border markers, are all pointing and naming and claiming things, a way for humans to feel a sense of ownership and to exert control. I see how these images with text are adding another layer of complexity.

RL: Yes. When making books, I often like to use words within the pictures themselves and I deliberately include these images with road signs and messaging to explore those notions of territory. The built infrastructure says so much.

TLC: And as a counterpoint, there are images of nature… a cat lounging in the tall grass, apples on a tree, fully ripe and thriving. In these pictures there is no sense of ownership, no concern for what side anyone is on. They’re outside of that construct. They’re not burdened by nationhood, identity.

RL: This is what I love about how you’re interpreting these, because those words, “nationhood” and “identity”, are so much a fixture of the problems we all have. And if you let go of that, you can see the commonality we all have instead of the differences.

TLC: Yes, I feel like Emmanual Eduma’s essay points to that as well, the humanity that connects below these surface concepts. I love how his essay is not directly related to the images in this book. It runs through obliquely.

RL: Obliquely, yes. Emmanuel’s story and my pictures complement each other without being descriptive of each other. Emmanuel is visually so adept and so sophisticated that his written perspective was perfect for what we were doing with this book.

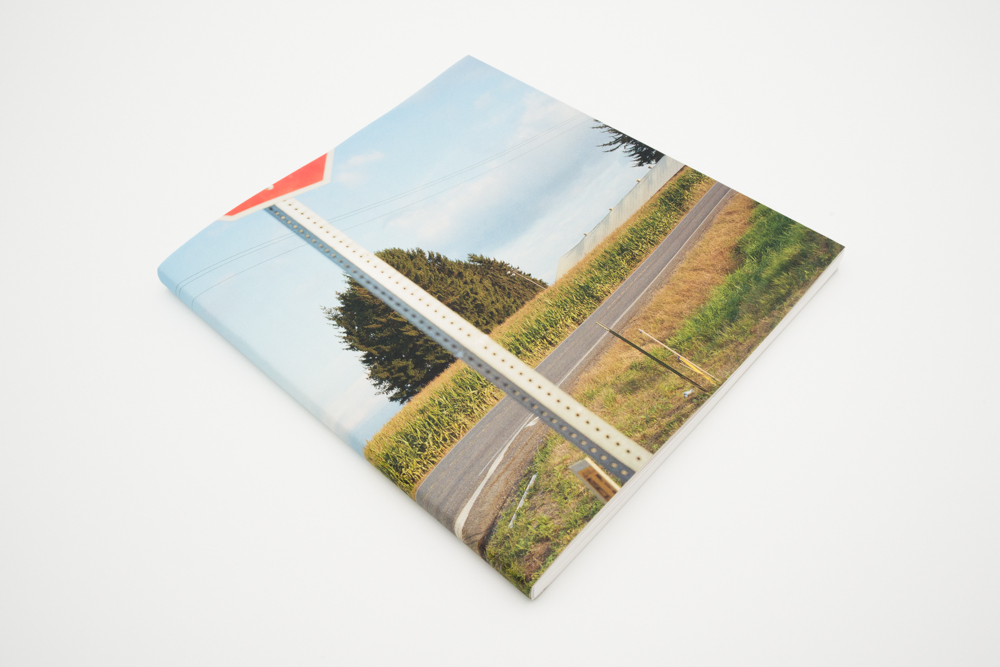

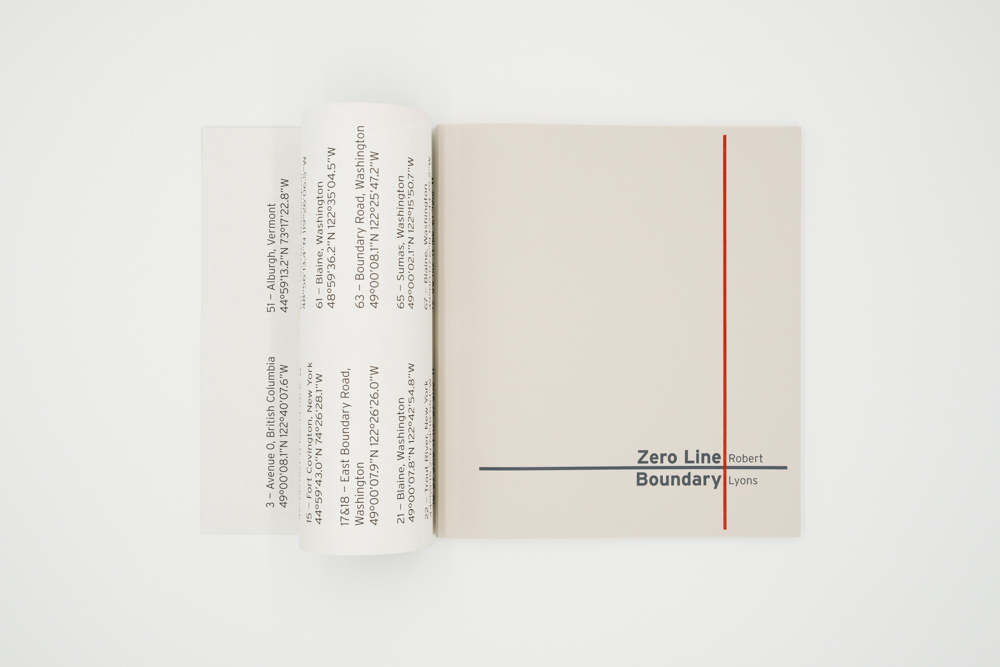

TLC: And let’s not forget about the book object itself. Can you talk about the cover? It’s the only image in color. And what is hidden underneath the dust jacket?

RL: There are a lot of little design things that make everything come together. The cover encases the book in color without disrupting the black and white flow inside. And when you pull the dust cover off, you have all these geo points, the latitude and longitude coordinates of where the pictures were made. I wanted to give a little added dimension for the viewer. It is more fun if you discover things along the way instead of having it handed to you right from the start.

TLC: Okay, I have one more question, and fair warning, you and I have had this conversation a million times. It’s about truth and photography. (Shared laugh and eye roll.) How are you navigating the balance between capturing the (air quotes) reality of the border landscape versus your subjective experience and what you’re choosing to point the camera at. Like what are you infusing versus what could be considered to be more objective?

RL: Well, the context is this real physical location and the very serious notions of nationhood and borders, yes. But it’s not meant to be objective and factual in that sense. The only exception is that I do give reference to where the pictures were taken with the geo points. So in that sense, I give you the territory, but I don’t give you the destination. The journey is the important part. I only visited certain places, there are many more that are left out. That is part of the subjectivity.

Zero Line Boundary by Robert Lyons is published by Zatara Press and includes the short story “Many

Metaphors Ferried Across the Border” by Nigerian writer Emmanuel Iduma. The book is available for

purchase through the publisher’s website.

Robert Lyons lives and works in Portland, Oregon. He has published numerous books and has shown

work internationally for over 40 years. He has taught extensively in the USA and Europe and is the

Founder and Director of The Hartford Art School International Limited Residency MFA Program at the

University of Hartford.

Zatara Press is an independent, small press, photography book publishing company created in 2014 by

Andrew Fedynak, to give a voice to a variety of projects through the medium of unique “Artist’s Styled

Photobooks” designed around the minimalist Japanese aesthetic view of Wabi-Sabi.

Follow Zatara Press on Instagram

Tracy L Chandler is a photographer based in Los Angeles, CA.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

J. Lester Feder: The Queer Face of WarMarch 11th, 2026

-

Curran Hatleberg: Blood GreenMarch 9th, 2026

-

Kiana Hayeri: No Woman’s LandMarch 8th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Vaune Trachman: Now IS AlwaysMarch 3rd, 2026