Photographers on Photographers: Helen Jones in Conversation with Robert George

Bob is my uncle. I’ve been fortunate to learn from him and talk with him about image-making through the years. Not only does he have a great eye but an interest and enthusiasm for others that is inspirational. I’ve been looking at his work my whole life, yet there are always new incredible pictures to be seen. This interview was done via email, in the months leading up to his 90th birthday. It felt like a big birthday and a good time to record some of his thoughts on the medium he has been a dedicated practitioner of for decades.

At his recent surprise 90th birthday party at the Vermont Center for Photography, John Wilis told a story about inviting Bob to talk with his photography classes at Marlboro College; “he would bring about fourteen three-ring binders, each with 200-250 postcard-sized images included. Each binder was separated by different subject matter or such a way of categorizing them. While handing out the binders he would typically be saying he did not know why I invited him to come speak to the class and that he did not have anything to say. He just photographed the world around him. As students looked and began asking questions a deep meaningful conversation on the nature of photography, his art, and the process unfolded and would continue for the three-hour class.”

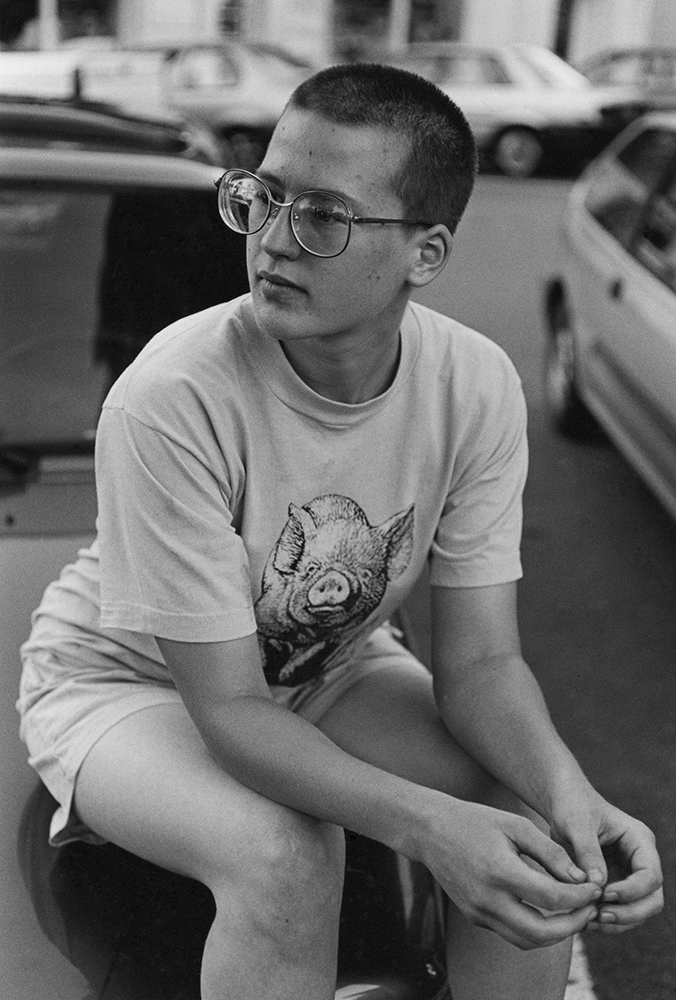

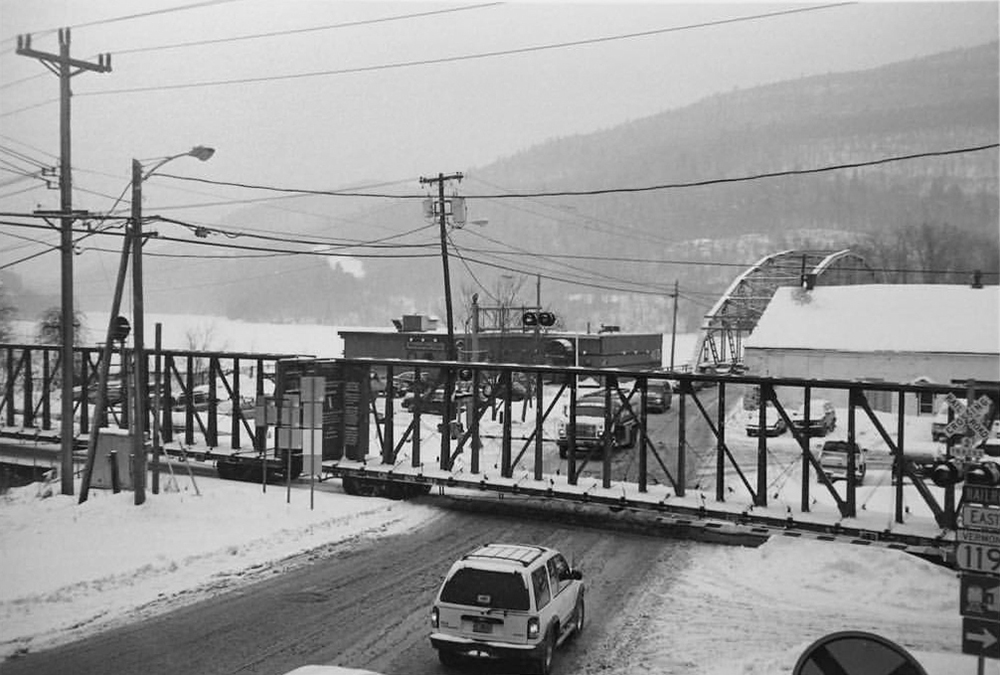

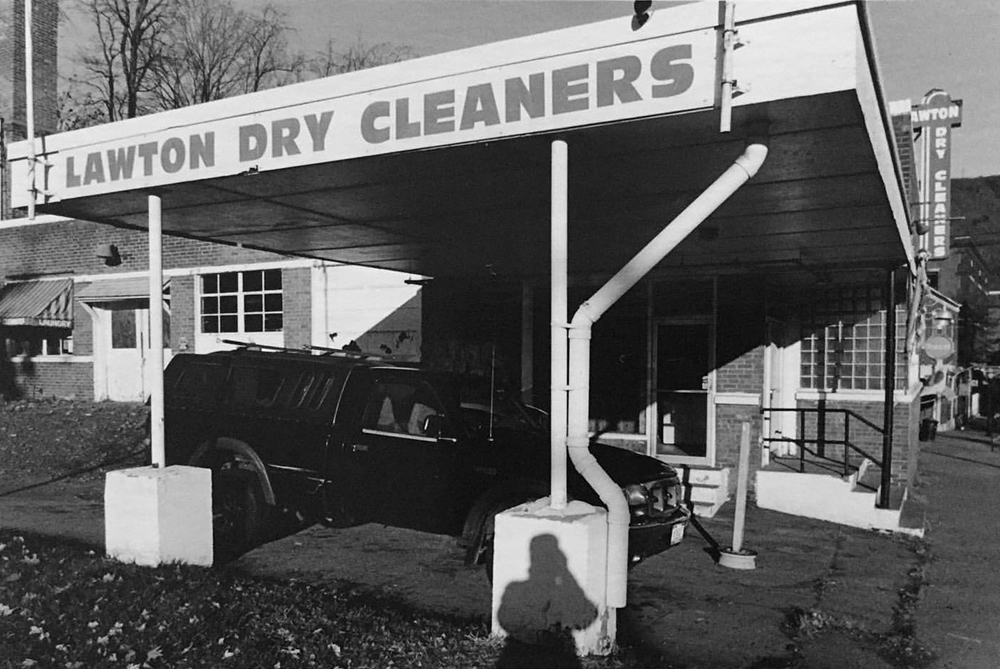

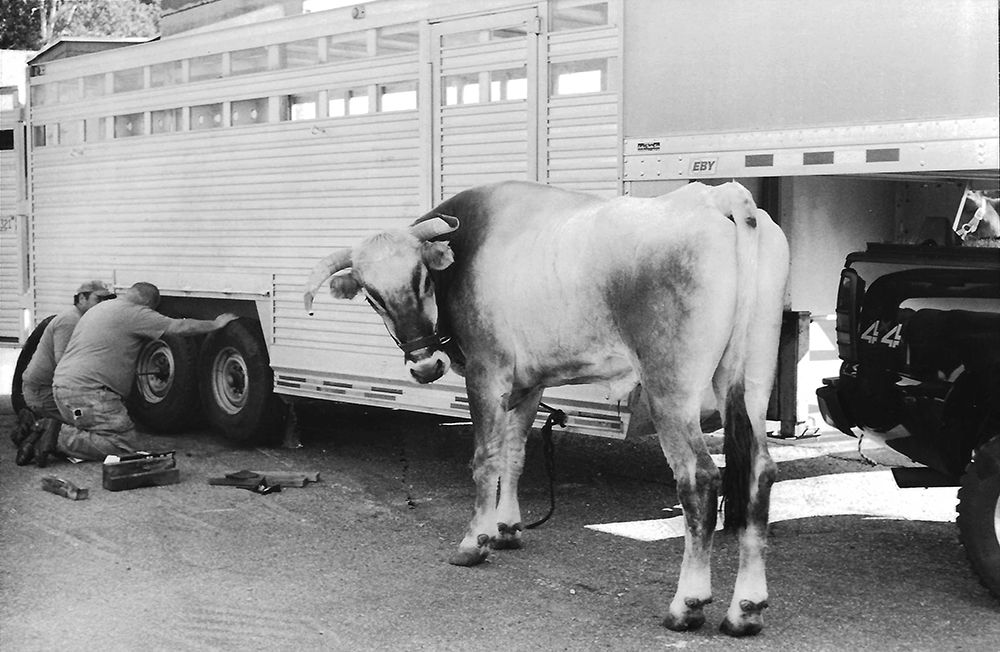

The binders John’s students pored over were still just a small portion of Bob’s amazing archive. From bike racers and cross-country skiers to teenaged loiterers and motorcycle mechanics; ferns, trees, cemeteries, graffiti, building sites; dogs in cars, and cows in parades, Bob has been depicting and celebrating life in Brattleboro through his photographs—and it is appreciated. His party was attended by multi-generational fans who remarked on how humble he is and how lucky the community is to be documented through his eyes.

Robert George is a photographer who has been documenting Brattleboro, Vermont, for more than four decades. Together with his wife Barbara he cofounded the cycling magazine Velo-news for which he was photographer. His images have also appeared in Sports Illustrated, Time, Newsweek, Vermont Life, and the New York Times. He has exhibited at the Brattleboro Museum and Art Center, Marlboro College, the Vermont Center for Photography, and the In-Sight Photography Gallery. He is often found around town with his camera.

Follow Robert George on Instagram: @robertgeorge440

Helen Jones: Hi Bob, thanks for agreeing to do this!

I guess an obvious question to start out with is when and how did you start making pictures? I know you photographed for Velo-news and the School for International Training (SIT) early on, was this the start of your practice? It strikes me that photographing for these institutions mainly involved documenting events, is that the type of work you started making? Has that changed over time? And if so, how?

Robert George: Since the birth of photography people around the world have documented their families. My mother took family photos and both parents saved early photos. I can’t recall any pleasure in getting photographed or any interest in old photos or photos in general.

In 1952, at age 19, I drove to California with a friend and had a Kodak brownie camera. This is the first time that I took some photos.

At 20 I was drafted into the Army and for two years I had little interest in photos. After a period of work, I attended MSU (Michigan State University) an agricultural school known as Moo U, and studied art and industrial design but still no camera.

It was at age 28 when I joined the Peace Corps that my mother gave me a 35mm camera. I spent two years in Bangladesh and took b&w and color slides. In 1963 my camera was stolen and it wasn’t until 1966 when Barbara (Bob’s wife) bought me a camera that I took photography more seriously. That is when I began photographing at SIT and other schools which continued until 1971 when Barbara got the idea for a newspaper (Velo-news, a cycling publication) which kept me busy for 12 or 13 years.

I had no formal training and there were few people to ask for advice so it was beginner’s books and magazines and some help from a local book designer. Seeing other photographers’ work and looking at art were a help but after 12 years of bike race photography I still felt I had a lot to learn and that’s when I started photographing Brattleboro.

Adopting the styles of those that I liked and choosing subjects that appealed to me—it became a challenge to construct the subject in a manner that pleased me.

HJ: Who were some photographers that influenced you early on? Did you seek out other photographers—I feel like you have told me many stories about meeting other photographers and artists and making pictures of them.

RG: Some of the photographers that influenced me initially were Clemens Kalischer, David Plowden, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Carl Mydans, Eugene Smith, Walker Evans, and Eugene Atget.

HJ: You talk about the “challenge” to construct the subject in a manner that pleases you— I imagine that you take that challenge to whatever you encounter during the day— I think this is essentially the idea behind street photography. Does that resonate with you?

RG: The challenge and fun is trying to make what I consider a decent photo no matter what it is. No place looks the same ever so if I’d care enough I could be occupied for a long time just going to the end of our street.

HJ: Having photographed the town of Brattleboro for decades, you have documented so many in the community. Did photographing bike races and other events prepare you to approach people and ask to photograph them? I believe people trust you to make good pictures of them. Do you think it’s because Brattleboro is a small town, and people see you with your camera often? Do you visit and chat with people before you try to make any photographs?

RG: Most of what I have photographed in Brattleboro was a result of walking around and hanging out. For the people, I prefer to know them a little bit and yes a small town helps. Photographing bicycle racing did help me approaching people.

HJ: I think you’ve been going to VCP (the Vermont Center for Photography) a lot, from its beginnings to this most recent new space. You have also been a supporter of the In-Sight Photography Project— speaking to classes and donating to the auctions. Can you talk about watching these projects grow? Do you think Brattleboro has a special connection with photography?

RG: I could name 50 photographers from when I started that were here or near here. There were three camera stores at one time plus Windham College, Putney School, Marlboro College, and several photo studios. I met some at the stores and also visited a few studios. I can’t recall learning very much from any of them other than from seeing their work. I forgot to mention the Camera Club which closed during the pandemic.

It was the same in other towns like Keene, Amherst, and Northampton but some years back things changed and people began coming to VCP because of the darkroom and events and also to show their work. I think Josh Farr had a lot to do with this as he was good at making connections and running the gallery. Now that VCP has a new larger space it has increased its popularity. Nashua, NH, has a smaller similar place that Josh knows about but that’s it. So because of VCP Brattleboro is more of a photo destination but I don’t think it has any more photographers than anywhere else.

The success of In-Sight is the teaching and fundraising. I always liked seeing what was going on there but don’t think I could have taught. In the beginning, I didn’t think it was a good idea but I changed my mind.

HJ: Why is that and what changed?

RG: From when I started photography I’ve had a love/hate relationship with it. I didn’t have much to spend on it, it was difficult and seemed a poor way to make a living. It seemed like a bad idea to teach kids a skill that they wouldn’t be able to afford or get a job at. However, John Willis and Bill Ledger saw things differently. They thought it was bad that kids were hanging out with nothing to do and they had connections in the photo world. What I didn’t realize were the social benefits of the program in the way that it operated so that maybe photography wasn’t the important part of it.

HJ: You have been photographing the art studio that neighbors your home and darkroom. What interests you about this group? How did you connect with them? Have you ever been involved with or wished for a collective such as this one?

RG: As for the artists next door, I was curious about them and Jonas (Jonas Fricke, a local artist) was my way to meet them. It was a little awkward at first because of my age but they are friendly and welcoming. I’m going to a gathering there this Sunday afternoon.

VCP is the closest to being a photo group but I can’t imagine anything similar to next door.

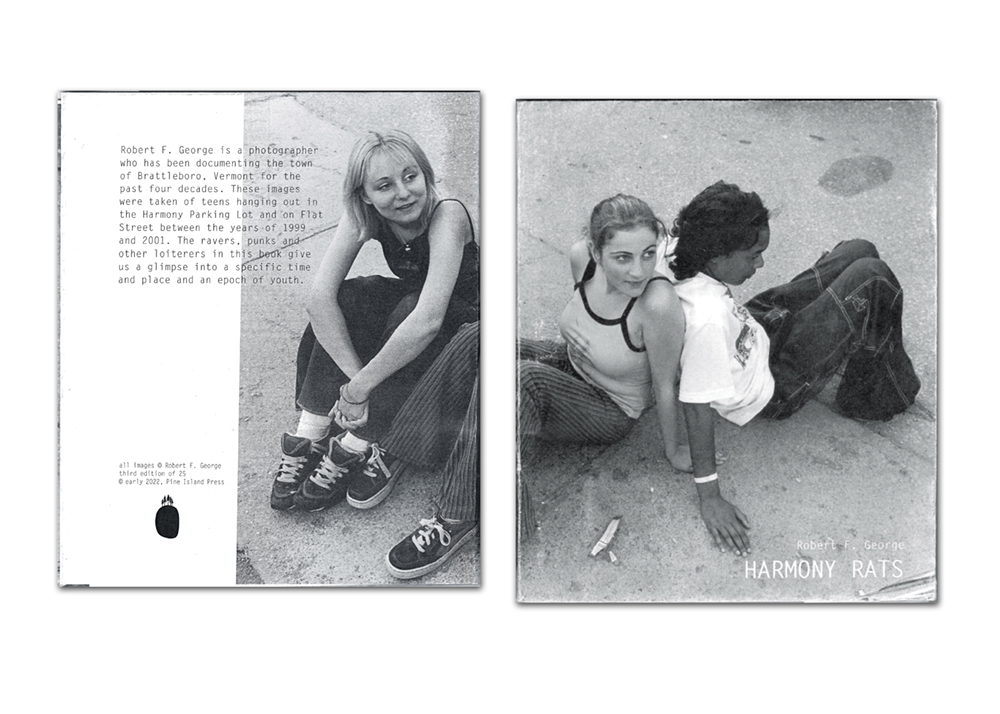

To further answer your question about why I was attracted to the collective next door, I did know that some were from the Tinderbox (an art studio and venue in Brattleboro active around 2005-2010) but I had never been there. They were like the kids who hung out in the Harmony Lot but more grown up. They seemed friendly and interesting and some made art but many made music. I’m way behind on appreciating their music. It turns out that Jonas made most of the art and it was nonstop. Also many are transgender and it was a little awkward at first but they are patient in allowing me to address them correctly and I tried to photograph them with respect.

© Robert George, Missy, Katie, and Sarah, 2000 / Cover of Harmony Rats, published by Pine Island Press, first pressing 2018

HJ: Yes, I believe Jonas was in many of the Harmony Rats pictures too, he was such a presence in town. He seemed to be a non-stop maker. I didn’t know him well but he had a wonderful positive energy that he put out into the world. His passing has touched so many current and former Brattleboro dwellers.

Once when you were telling me about why you were drawn to photographing the Harmony Rats you described them as “a caring group”. I think that gets to the root of why you make such lovely portraits and why people let you photograph them and want to be photographed by you. You photograph everyone with respect. You seem genuinely curious and interested in what people are doing with their lives, even if their lives are different from your own. I think people sense this.

What about the distribution of photography? There are so many ways people encounter images. You are really great about giving people prints — often postcard prints of your work—I see them around on people’s fridges all the time. And now you have Instagram. How has that changed the way you share work? Has it expanded the number of folks that see your images?

BG: One of the things that has kept my interest in photography is books. It’s great how you can go back to them to enjoy and see new things. I was fortunate that you did those two books of my photos and they were well printed.

HJ: I agree with you about books, that they allow you to revisit work and get to know it in a special way. I was very happy to put out those publications (Harmony Rats and Dogs of Brattleboro) for you! Are there a few books that you consider particularly important to you that you could talk about? What did you find in them that was influential or meaningful to you?

RG: It’s hard to name just a few but I’ll try: FSA photographers like Jack Delano who was an immigrant. Worked hard and was good with people. Marion Post Wolcott a fearless woman who liked people and had a good sense of framing. Russell Lee loved people, worked hard, and could photograph almost anything. Gordon Parks and Roy DeCarava did great work with Black communities.

Don Normack did a book called “Chavez Ravine” which had an effect on me. He seemed to love the community he photographed. Another favorite book is Railroad Men by Simpson Kalischer. I’ll show it to you sometime. Andrew Borowiec does great backyards with growth and buildings. Pentti Sammallahti has the best dogs in his great photos. Eugene Smith was a great 35mm photographer as was Henri Cartier- Bresson.

Lee Friedlander is hard to believe for all he has done.

Peter Sabin and his daughter Anika brought me a small book by Ming Smith. She really took liberty to portray Black life in a deeply felt way.

As for Instagram it’s a way for people to see something of what I do and has expanded the number of people who see it but I still have uneasy feelings about it.

HJ: What makes you uneasy about Instagram? Is it the way people interact with images on that platform?

RG: Instagram is a way for people to see something of what you are doing but they are not holding your print in their hands and comments are rare. I click on friends’ photos just to support their efforts and I’m sure the same is done for me. Even when you display work in a group show you don’t get many comments. You end up doing it for the challenge and the pleasure of feeling like you got something good.

HJ: Yes, Instagram is a very quick glimpse at what people are up to. It is nice to be able to share with friends near and far, and maybe some new folks, but I think it can also feel really overwhelming. I think most photographers make images for themselves, because they feel compelled to, but it is hard not to want other people to see them.

I am reading the book, To Photograph Is To Learn How To Die by Tim Carpenter, and it is packed with quotes. I would love to see what kind of system the author used to organize it all, I am picturing many color-coded index cards, but who knows? I wonder if you have any photography quotes or quotes that influenced your practice that you would like to share?

RG: I think I sent this quote to you before but am sending it again because it hit me.

“There is a vitality, a life force, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and be lost. The world will not have it. It is not your business to determine how good it is, nor how valuable it is, nor how it compares with other expressions. It is your business to keep it yours clearly and directly, to keep the channel open. You do not even have to believe in yourself or your work. You have to keep open and aware directly to the urges that motivate you. Keep the channel open.”

-Martha Graham, “The Life and Work of Martha Graham” by Agnes de Mille

HJ: That’s a lovely quote, I do think you have shared it with me before, but it’s good to read again.

HJ: And I think it ties into another thing I wanted to touch on, which is that you have had an incredibly long and dedicated practice. You always have a camera on you, you are committed to making photographs, and as far as I can remember you have always had a darkroom. Do you have any advice on how to maintain that kind of motivation in the long term?

RG: Do it for your own enjoyment. When that stops, wait another day.

HJ: I know this conversation between us will continue, but for the moment I will stop barraging you with emails. Thank you for talking with me!

Helen Jones holds an MFA from the University of Texas Austin and a BFA from the Massachusetts College of Art. Since 2011, she has run Pine Island Press producing small-run books and zines including Incandescent, a bi-annual publication showcasing emerging photographers. Her work explores interactions between people, places, and landscapes. Recently she has been included in exhibitions at ShedShows (Austin, TX), Greensboro Project Space (Greensboro, NC) UnSmoke Art Systems (Braddock, PA), and the Visual Art Center (Austin, TX). She is currently a lecturer at the University of Texas at Austin.

Follow Helen Jones on Instagram: @helenjonesphotographs

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Jason Lindsey in Conversation with Areca RoeApril 21st, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: J Wren Supak in Conversation with Ryan ParkerApril 20th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Josh Hobson in Conversation with Kes EfstathiouApril 19th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Leonor Jurado in Conversation with Jessica HaysApril 18th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Sarah Knobel in Conversation with Jamie HouseApril 17th, 2024