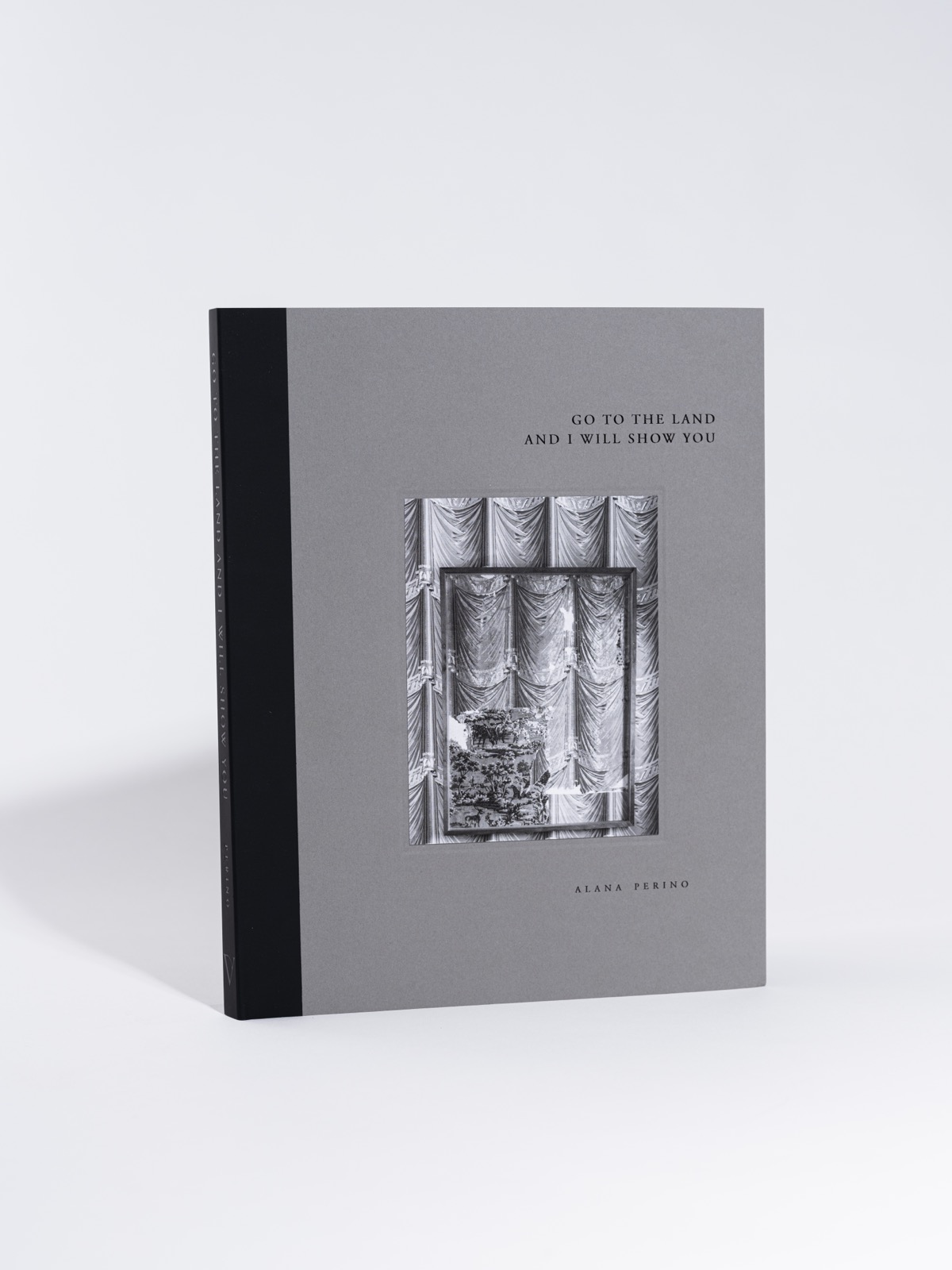

Alana Perino: Go To The Land And I Will Show You

Some symbols of the American mythos come strong to one’s mind. Flags, documents, wars, even specific dates. The kind of things that are so deeply ingrained in our psyche as Americans that we know them at a glance. Those are not the symbols on display in Alana Perino’s first monograph, Go To The Land And I Will Show You. Instead, Perino finds more subtle and insidious representations of the stories we tell about ourselves at the national monuments scattered around the country. Miniatures, swamplands, historical recreations. We propagate the same stories over and over again, spreading them to even the rock formations that have been here long before us.

I was immediately taken with Alana’s project when I encountered it more than a year ago. Now, after many days of hard work, I am honored to have published this book under the new press Valley Books. But I always love hearing from other thinkers and theorists about the books I fall in love with. That is why this conversation between Alana and Jonathan Mark Jackson is so special. It is a meeting of two minds, people who think and care deeply about photography. And both Alana and Jonathan are young, ready to make new waves in our small world. The care with which Jonathan interprets the book should be the standard we all hold ourselves to when reading these visual texts. I hope you enjoy this conversation as much as I did. -Drew Leventhal, publisher of Valley Books.

Today Alana Perino is in conversation with Jonathan Mark Jackson to discuss their new book, Go To The Land And I Will Show You, published by Valley Books.

Jonathan Mark Jackson: Go To The Land And I Will Show You encompasses a decade of photographing US national parks, monuments, and historic landmarks. Can you describe where you were ten years ago? When did you perceive that this project was beginning to take shape?

Alana Perino: I consider the start of the project to be roughly the winter of 2013. I had recently returned to my home in the United States from Israel Palestine. I had been living there for a year, working at times as a farm hand and others as a photojournalist. I had arrived via a Birthright trip shortly after finishing my undergraduate studies and neglected to take the flight home. The country is very small, the size of New Jersey, and I was determined to see as much of it as I could while I was there. I’m not sure if this is still the case but at the time hitchhiking was common and considered a safe practice. This, and the affordable bus routes were how I managed to see much of the country in a short amount of time. I was photographing then, in general for my work as a journalist for a news agency based out of Jerusalem, and for the preservation of memory, but also as a way to contend with the cognitive dissonance of the colonial practice I slowly realized I was engaged with.

I understood while on Birthright that I was a part of a zionist program, and therefore a colonial project.

I don’t consider myself to be a Zionist by definition and I was secure at first in the use of this opportunity as an entry point into the country, a way to arrive somewhere through an agenda that was not my own in order to align with a practice of navigating cultures and landscape with a more nuanced and empathetic approach. However, it became clear to me that my goals were simply part and parcel of a value system carefully curated for Jewish visitors like me implemented through structures like Birthright. Even though I was visiting locations the program actively discouraged us from engaging with – Palestinian cities, towns, the West Bank – the very privilege of being able to travel there, to move my body between checkpoints, barriers, and borders, was a colonial exercise. This mobility itself was afforded to me through systems of colonial power through a “right” of birth. I realized my obsession with traveling and “seeing” as practice for personal growth, the ability to do so and the decision to exercise that capacity was not as radical as I once thought it to be. The practice was merely a natural extension of colonial practices made visible through the very language inherent to it: to explore, to survey, to accumulate. Israel as a state is very similar to the United States. There is an emphasis on experiencing the place, its landscapes, its cultures, as a way to learn its history and by proxy as a way to learn about yourself as an inheritor of that land. The land and its culture and its history “belongs” to those, granted with the perceived given right of birth, who choose to let it envelop them. This for me became the working definition of what I consider to be a “heritage site.”

When I returned to the United States, I had an opportunity to relocate my life from New York where I had grown up, to California in community with friends. We drove. I had only just learned how to, for this trip. In the book I tell a story of passing the Gettysburg Battlefield on our way. The urge I felt to stop and look, and the refusal of the rest of my party to allow me to do so. I had been photographing along the way, again as a practice of preservation in the face of the unfamiliar. Those photos did not make their way into this book. But it was at that moment passing Gettysburg that the familiar urge to see, to experience, to collect, through encounters with landscape began in earnest, and developed through the years into an obsession with “American” heritage sites that I was really only able to shake ten years after my engagement with it began.

JMJ: These observations remind me of the tenants of silences defined by Michel-Rolph Trouillot in Silencing The Past: Power and the Production of History. A text that was pivotal to us both during graduate school. In it Trouillot asserts that silences develop in historical production in four moments:

“The moment of fact creation (the making of sources); the moment of fact assembly (the making of archives); the moment of fact retrieval (the making of narratives); and the moment of retrospective significance (the making of history in the final instance).” (Trouillot, 1995)

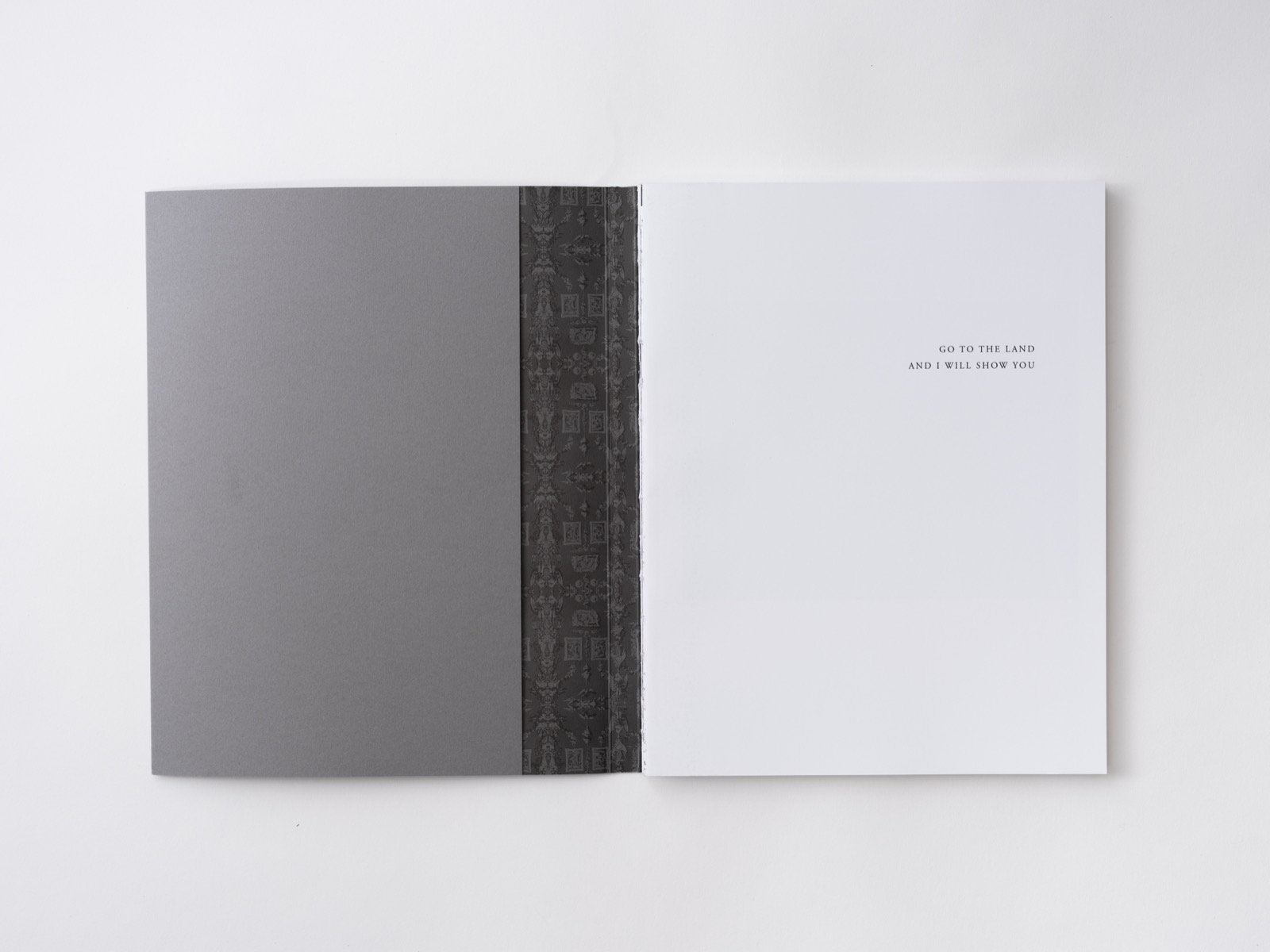

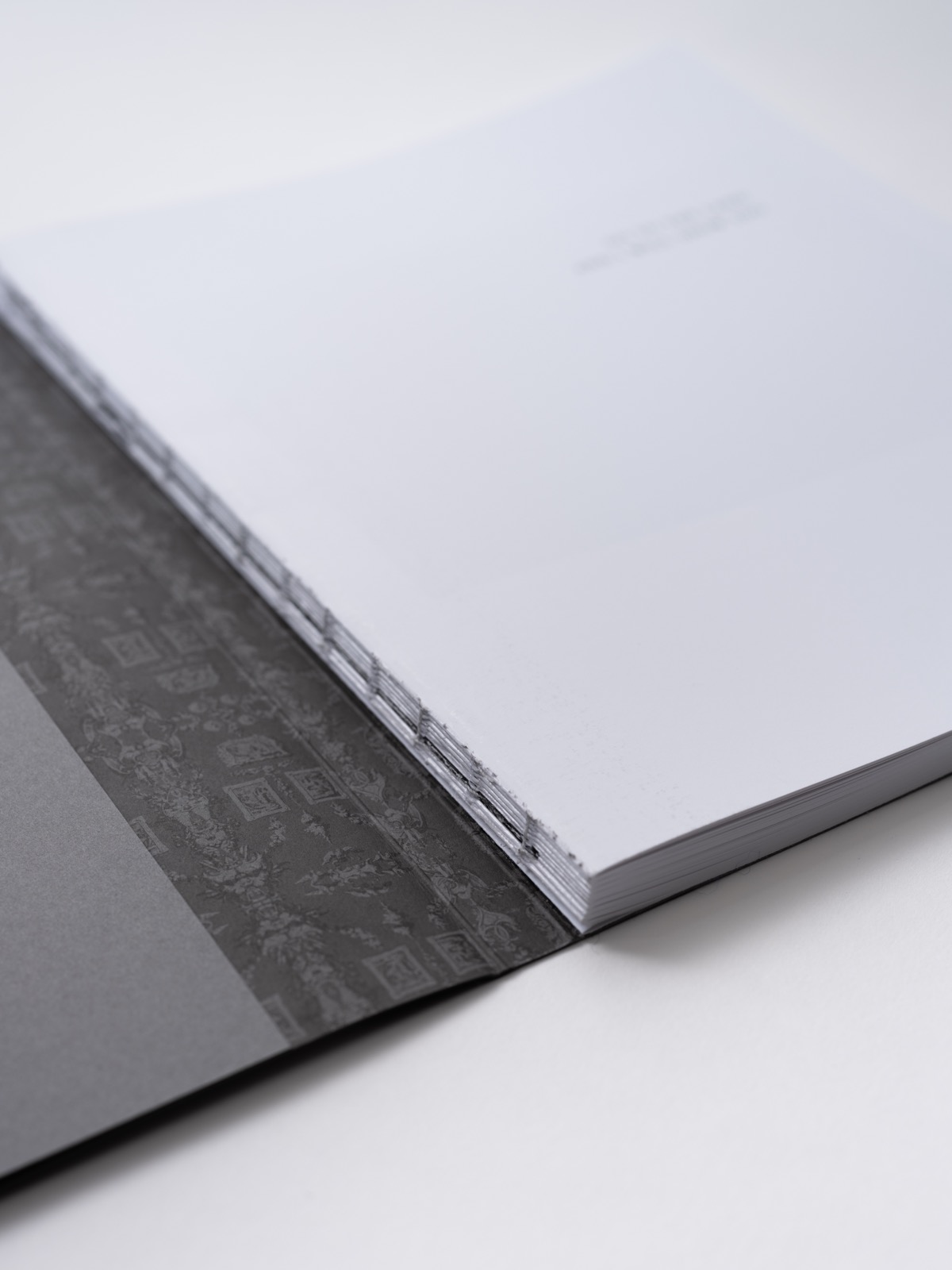

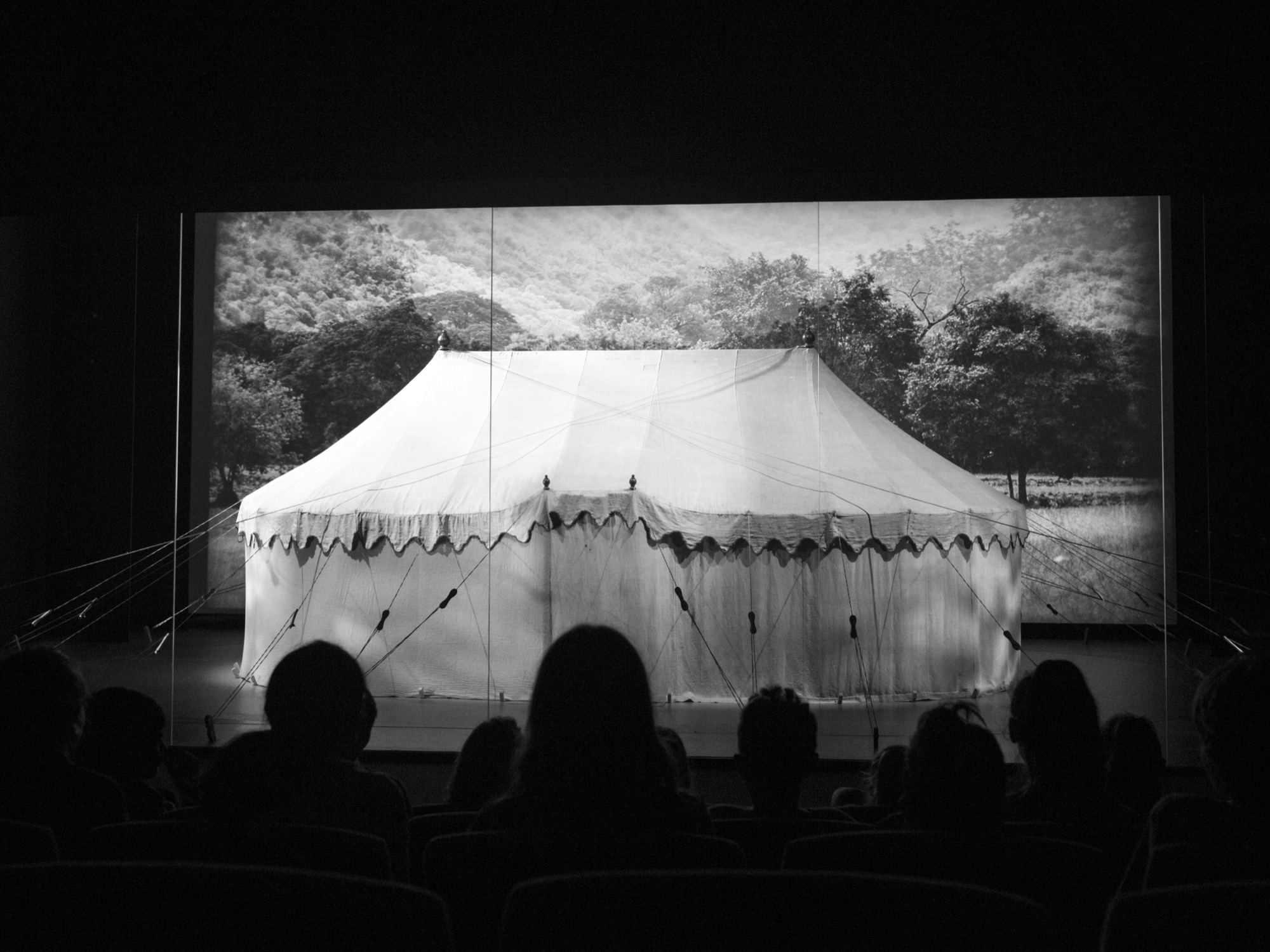

Your experience also reminds me of dramaturgical devices to create perception shifts for an audience. I’ve always thought that Trouillot’s arguments and definitions are methodologically theatrical. Go To The Land… dramatizes and activates historical silences in particular ways. In fact, the frontispiece photograph is a doubled image of toile and a painted stage curtain. This image alerts a viewer that a performance is about to begin.

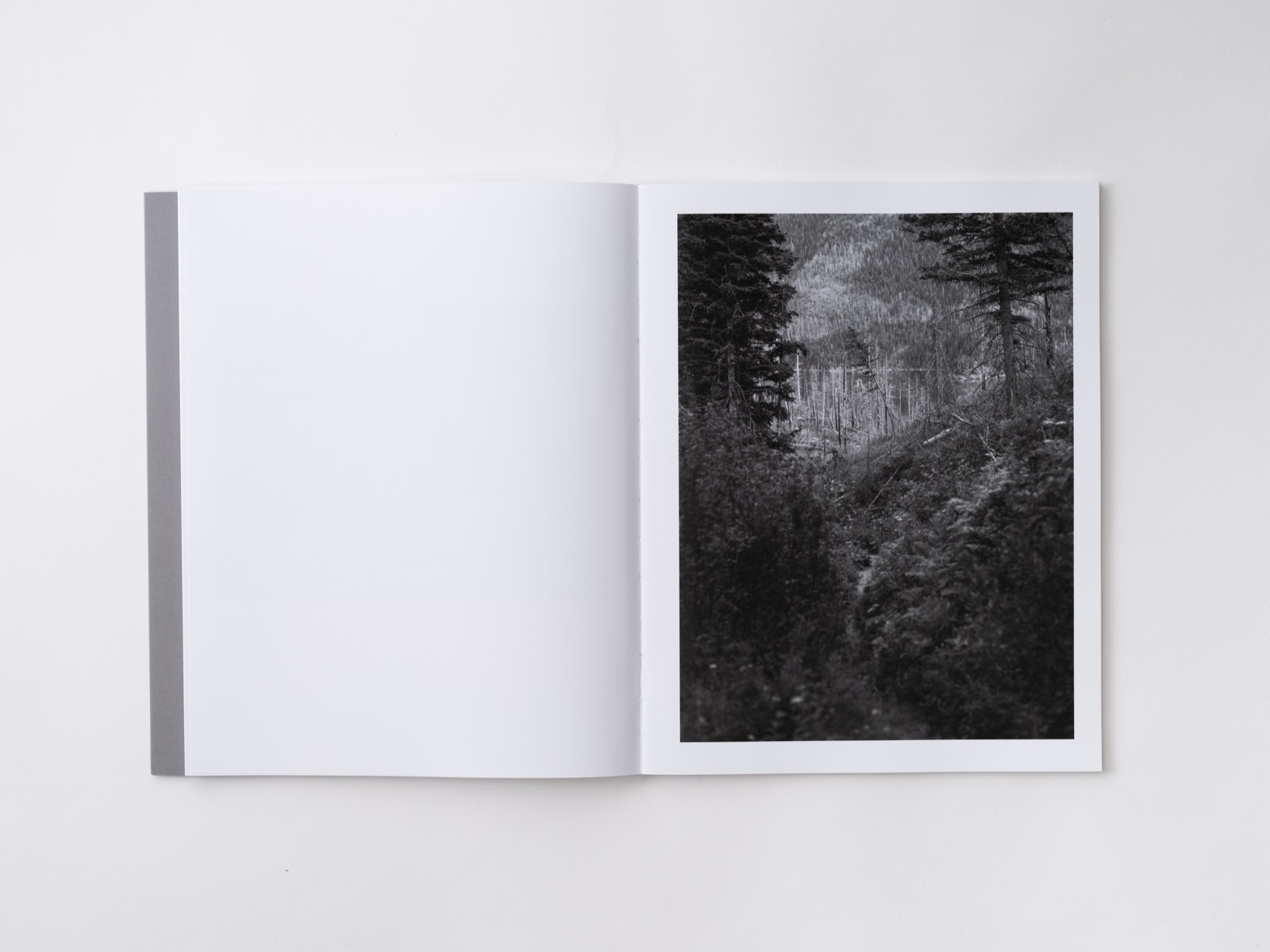

Let’s discuss the structure of the book closely. Three photographs precede a title page. Within them I, the viewer, am placed into a curtained room, gazing up towards a plaster ceiling with a cavity revealing its foundation layer. I turn the page to a landscape of chopped trees that are curiously scaled. A bevel of space in the clouds, and the smallness of the trees lead me to think that this space is a miniature or a diorama. I turn the page once more to find a portrait of an anonymous body of water, whose dark waves suggest that it is an oceanic body. These three photographs direct me to study both interior and exterior space carefully. Everything is not what it appears to be.

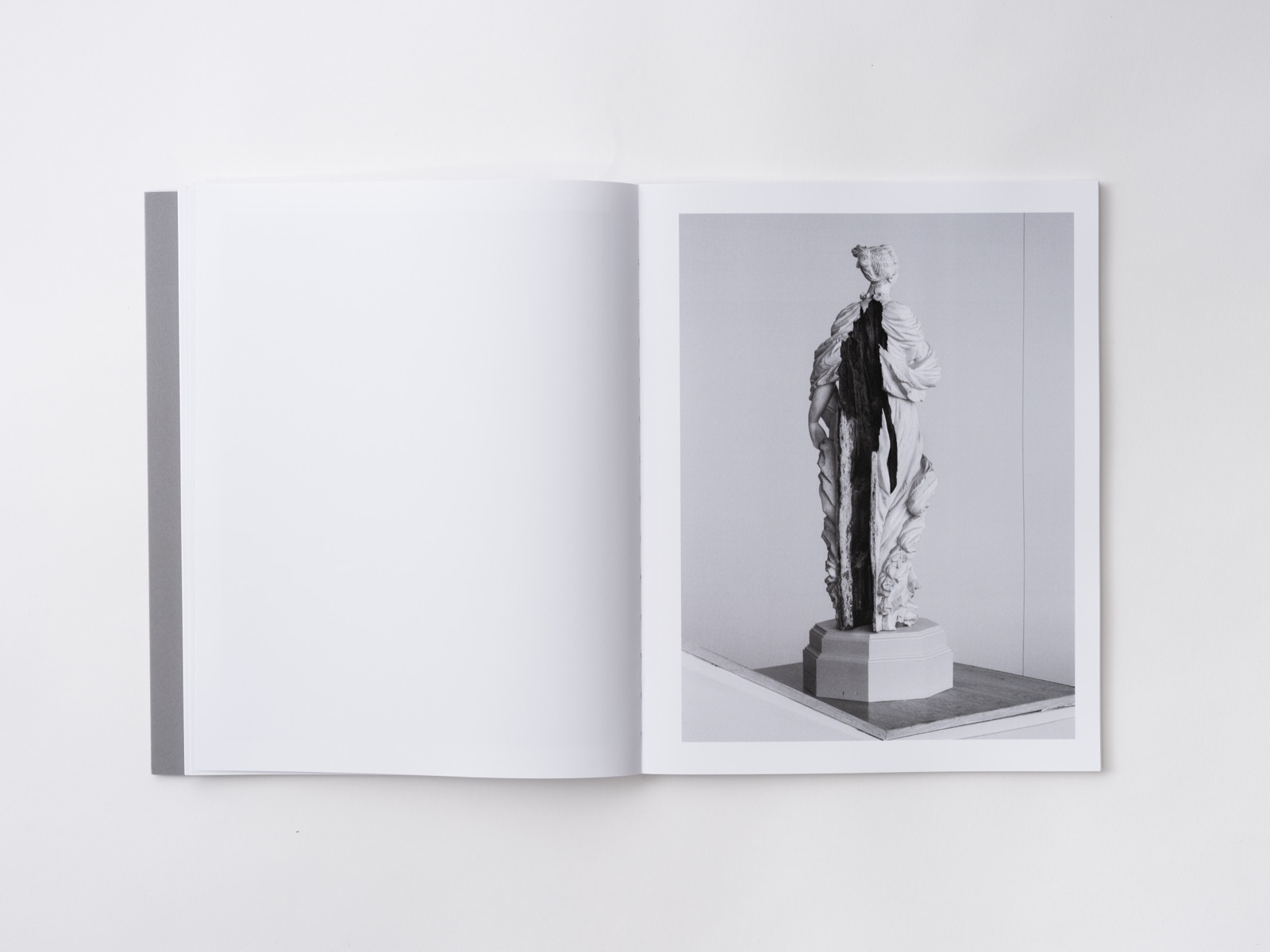

Following the title page is an unbroken sequence of photographs that depict a mutable landscape, where the simulated and the real push up against one another. Desert fauna grows against a wall painting of dry and rocky landscape, tourists seen from a distance merge with plastic figurines frozen in battle, and almost all architectural spaces (houses, rooms, bridges, arches) are supported by risers or scaffolding.

These photographs are untitled and unnumbered on the page. Following a photograph of a tunnel structure, you offer seven narratives that succinctly detail your journey through these spaces. Simultaneously naming yourself as photographer, author, and protagonist. A close portrait of an illuminated fresnel light (perhaps from the interior of a lighthouse) is then followed by a sequential list of sites visited and photographed. This list acts as a coda, in that it reveals the notable sites and parks I sensed within the main sequence, however it doesn’t rename each photograph. What led you to making these structural choices? How, if at all, do you think the form of the book creates or dispels narrative?

AP: There were times in the early stages of bookmaking where I was paralyzed by the inundation of images I had collected, the bulk of them in terms of volume and the varieties of places, people, objects and perspectives they represented, which at the time all seemed related and relatable to a vision of the contemporary “American” landscape. There was simply too much to sift through on my own and so I turned to community for help. I applied for the Image Threads Collective’s Photobook Long Term Program. Slowly, with the guidance of amazing thinkers and image makers like Jenia Fridlyand and Tim Carpenter, the images began to organize themselves into categories, some which revealed themselves as stepping stones for understanding the history of landscape photography in the US, others which merely encapsulated the peculiarity of what I saw but not how I saw it. Eventually a group of images emerged that pointed to, quite literally, the strangeness of a landscape curated to affirm the catastrophe of American Exceptionalism and the failures of my seeing adequately enough.

The goal and the challenge was to convey a tired narrative of historically perpetrated violence, justified by the mythologies of nationalist birthright, without reifying those same values. I chose to do this primarily through obfuscation, by making things difficult to see, and by refusing to identify what is beheld. The sequence is designed to orient the reader to a place of disorientation and to enmesh the perceptions of me, the photographer and author, as both a guide and a protagonist on a journey through a kind of sublime disillusionment. I have come to know that the first instinct of my reader is to ask “is this real?” I hope that by the end of the book the reader comes to know that all of it is real and that none of it is real. That the very structure and value of reality functions as agenda, especially in photography. That the landscape has an agenda, that the caretakers have an agenda, that I have an agenda, and that the reader themselves have an agenda. When Drew Leventhal approached me about collaborating on this book together, I knew he was the perfect co-conspirator in this project because he understood this. And he understood the insidiousness of the “American” agenda, and the ways it imposes itself upon the land in order to create desire. A desire to see, which is a desire to know, which is a desire to own. To know if a photograph is “real” or not is to own it in a way. To not be riddled with the frustrations of its unknowability. My efforts in the structure of the book, the push towards disorientation in the images and in the sequence, the inclusion of sites visited without naming individual images, are all working towards the goal of undermining what the reader can and cannot own of a landscape rendered battlefield in the assault of colonial ownership.

JMJ: Ownership, possession, and obfuscation are key terms here. Each is entangled in the development of photography itself, and it feels like all us (photographers, “lens-based” practitioners) are working to disentangle these imagistic conditions. A notable distinction between this work and your recent portfolios In Conditions of No Light and Pictures of Birds is the absence of portraiture. Having witnessed your working methods closely for a few years, I know that self-portraiture and performance aid you in articulating ideas around historic narratives, myths, and folktales. Although there are figural works in this book (particularly present through animals and statues) your attention to landscape and scale supersedes the development of a central character. Do you feel a difference between these two methods of working, portraiture and landscape?

AP: I had made very few strong portraits over the course of this work and I found myself clinging to them so forcefully that I was arranging and rearranging the entirety of the project so they could live comfortably inside of it. I eventually found it necessary, at the urging of both Jenia and Tim from the LTP program, to remove them altogether, if only as an exercise, to see what might take shape without their influence. I assured myself that after settling on a sequence of landscapes that the portraits would find their way back to the book, but they never did. I tried on many occasions to have them return but I realized that they did not serve the work. After some imposed distance, I no longer missed them. This is not to say that I didn’t try to make portraits. I photographed tourists, custodians, reenactors, so many reenactors. I don’t think I knew what I wanted from those images and because of that I think they all accidentally became caricatures of what we have grown to expect.

In 2019, which was approximately six years into Go To The Land…, I began photographing my family in Florida. My stepmother had been recently diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s and it was clear that the relationship I had with her and the family structure for which she acted as a foundation was quickly slipping away. She didn’t like to have her picture taken, and clearly I was not very good at making portraits so the challenge of the work seemed insurmountable. But it seemed like the best time to try. I lived with her and my father, and my sister, a nurse who was caring for our mother, and my niece for sometime during lockdown in 2020 when her hospice treatment began. In that time my sister’s son and his father also visited from time to time and I made portraits of all of them. We were all cramped in a home that was too small for us all to occupy at once and suddenly our family structure began to fall apart when we were no longer ushered by the leadership that my stepmother, who was now nonverbal, provided for decades. We became different people, we became enmeshed and we became each other. My stepmother and I were sleeping in the same room. She on the bed hospice brought to our home, and me on the couch with a divider between us. She would talk in the middle of the night to invisible visitors, when she had been incapable of talking during the daytime. She said she was scared and so was I.

I would sit with her, and learn where the ghosts stood based on her eye movements. And I photographed them. This practice of photographing ghosts changed the way I approached portraiture. With Go To The Land…, I developed a practice for photographing a simultaneous absence and presence in the landscape. This was a natural extension of the heritage sites I was engaged with because they were already eulogized spaces. It took some time for me, and a proximity to death, to know that portraits are also eulogized spaces. And that a portrait is something like a corpse. And that a corpse reminds me inevitably of my own death. My portraiture practice began in earnest, as it exists today with its emphasis on performance and self-portraiture when I accepted fully that to make a portrait was to photograph as if I was photographing myself.

But when this realization came, my photography of heritage sites was near its completion. Or at least I wanted it to be. I was halfway through the book program and was about to enter the graduate program at RISD. I felt the pressures of time over a project that I had dedicated what was nearing closer and closer to a decade. Most importantly I no longer felt the desire to drive from battlefield to battlefield to see and photograph a landscape of ghosts. I decided to use my time at RISD to flesh out the project of my Florida family, to begin a project with my New York family centered on the performance of the self-portrait and the home as stage, and ultimately to finish the Go To The Land… work by completing this book.

JMJ: Photographing ghosts is a beautiful sentiment, and one I share with you from different origins. An internal perception shift occurs when you point the camera at something that is spectrally impossible to “capture”. Your work affirms that ghosts, imagination, and memory are functionally the same things. The last text piece in Go To The Land… places you at Niagara Falls, and that photographing it (or perhaps being unable to photograph it) also clarified that this project was coming to an end. A level of historic poetry is not lost to me here. Throughout my engagement with the book, I felt guided to think of your work as a counter-narrative to American landscape painting. The ghost of Frederic Edwin Church’s Niagara (1857) looms in this dialogue as a seminal piece that you are critiquing. For the Hudson River School painters, as well as many others, Niagara Falls symbolized the formation of an American consciousness. Which, in turn, transformed the land into one of the earliest commercial geographic tourist destinations. In your experience, returning to Niagara Falls at the end of a journey rather than at a beginning, you aptly defined the site as being, “…a sublime metaphor for the insidious myth of manifest destiny.”

This final text piece transformed the “I” within the title of the book for me. The pronoun shifts from being just a representation of yourself, into being the critical “eye” of the contemporary effort to craft a decolonized relationship with the land. The final photograph of the book, a scene of foggy or smokey trees, suggests an elemental transition. Making a clearing of something that has been rooted. After all this work, how does it feel to conclude and share what you’ve seen? What might be on the horizon for yourself (photographically or personally) in the coming future?

AP: I cannot begin to describe how thrilled I am that Frederic Edwin Church came up for you as an image maker in your reading of the book. That painting haunts me too. I’m haunted by other images and their makers, Timothy H. O’Sullivan and Carleton Watkins for instance, but none as much as Church. I had never been to Niagara Falls before visiting to photograph it, even though it was a landmark so close to where I was raised. So ending with that park felt much like a return home. Of the fifty photographs in the book, which were made over the course of ten years, three of them are from that day I visited the Falls, which was the last day I photographed for the project. I realize this is breaking my own rule about refusing to locate images but I am tempted to admit that one of them is the image you referenced of the oceanic dark waves that precedes the title page. I almost didn’t go that day. I felt so sick. But I’m thankful that I did. I don’t think the project would be the same if I hadn’t gone. I believe it’s possible that I wouldn’t have been able to even finish the project until I had gone.

The title Go To The Land And I Will Show You, is a quote from Genesis. G-d speaks to Abraham, telling him of a land that will be the birthright of his progeny. This is of course the birthright of the territory we now call Israel and Palestine, that is referenced in the nationalist projects of Zionism. In this case the “I” is G-d, divine intervention, and destiny; three of the mythologized forces behind the national illusion of Manifest Destiny. The “I” in the title is still those things, and also American Exceptionalism, and also myself as a photographer, protagonist, and guide. I very much wish to work towards a decolonized relationship with land, not just where I live, but in how I encounter it, how I move through and across it and how I bear witness to it change, and transform. I am humbled by the suggestion that the work of contemporary landscape photographers, and the work in the book, is an effort to do just that. There is a walking meditation I practice where you visualize not moving atop the surface of the earth, but planting roots with each step, moving the ground underneath and behind you, removing those roots, and planting them again with your next step. This is a grounding practice, but I think also a practice in moving through difficult transitions with acceptance and compassion. I am relieved that the project has reached a kind of conclusion, and grateful for the obsession which ushered me though so many modes of knowledge production. I’m especially grateful that the compulsion has died and made space for new ways of seeing.

My focus is now turned towards expanding my practice beyond the landscape, beyond the form of the book, and in some cases beyond the image. I spoke earlier about the incorporation of portraiture into my project Pictures of Birds. That work is concerned with transformations, structural, physical, spiritual, and otherwise, in our encounters with aging and with death and remains rooted in the conceptual world of photography and the photobook. I am hoping to let it leak into the physical space of the exhibition as it develops. I have recently made several mockups of this work as a book, which will hopefully be completed over the next few years. My newest endeavors are centered around my mother’s apartment in New York City, the apartment where I grew up. In this work, In a Condition of No Light, I am striving towards gestures of performance, installation, and sculpture to examine and rethink how the home serves as a stage for the inheritances of heteronormative domesticity, eulogized space, and rituals of Jewish assimilation into whiteness. I had the opportunity to make several iterations of these installations while in graduate school, one at RISD Brown Hillel, one at the Rhode Island Convention Center, and one in New York City’s Microscope Gallery which will be on view through August 24th. These projects are highly personal in nature. They require very little traveling, at least during the photographing itself, and demand much stillness and compassion. It is exciting to be working on something so different from what I had been otherwise occupied within the “American” landscape and to be pushing into new territories of intellectualizing, feeling, and transforming inheritances that are closer to home.

JMJ: Despite the commercial enterprise surrounding it, each time I’ve visited the falls I’ve felt like its rush clears out my eyes. Thank you for the revelation of that photograph. I am tempted to ask you more and more about these burgeoning methods of melding photographs and sculpture. As well as what appears to be a new engagement with color photographs. But, I will save them for the near future. Go To The Land And I Will Show You is available now from Valley Books. Thank you Alana.

AP: Thank you Jonathan. It’s such a pleasure to talk shop, ghosts, silence, and seeing with you, always.

Alana Perino was born in 1988 and grew up in New York City, the North Fork of Long Island, and the stretch of highway between the two. They studied European Intellectual History and Photography at Wesleyan University, where their questions concerning the nature of belonging were only further problematized. After working as a photojournalist in the Israeli-Palestinian territories, skeptical of the privileged nature of their stay, Alana returned to the United States. They lived in California for eight years, crisscrossing the country to photograph “American” heritage sites. In the summer of 2021 they returned to the East Coast to photograph the people and places that raised them. Alana resides on the unceded land of the Pokanoket, Wampanoag and Narragansett in Providence, Rhode Island where they recently completed the MFA Photography program at RISD. They are still searching for home.

Instagram: @lanapino

Jonathan Mark Jackson was born in 1996 and raised in Detroit, Michigan. He holds a B.A. in Art and The History of Art from Amherst College, and an MFA in Photography from the Rhode Island School of Design. His work focuses on retouching the archives of colonial racial slavery, to visualize the haptic and sonic quality of phantom Black subjects. He is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor of Photography at Boston College.

Instagram: @_jmjackson

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW PressApril 7th, 2024

-

From Here to the Horizon: Photographs in Honor of Barry LopezApril 3rd, 2024

-

Shinichiro Nagasawa: The Bonin IslandersApril 2nd, 2024

-

Kristine Nyborg: Learning to Speak BearApril 1st, 2024