Janelle Lynch: Endless Forms Most Beautiful

I first met Janelle Lynch through Zoom squares, while taking her class at Maine Media some years ago. Since then I interviewed her for my Mini Musings series and I also had the pleasure of being her teaching assistant through Santa Fe Workshops Online. In every interaction with Janelle I’ve been moved by her ability to find the extraordinary in the ordinary and her deep connection to the natural world, which is so often reflected in her work.

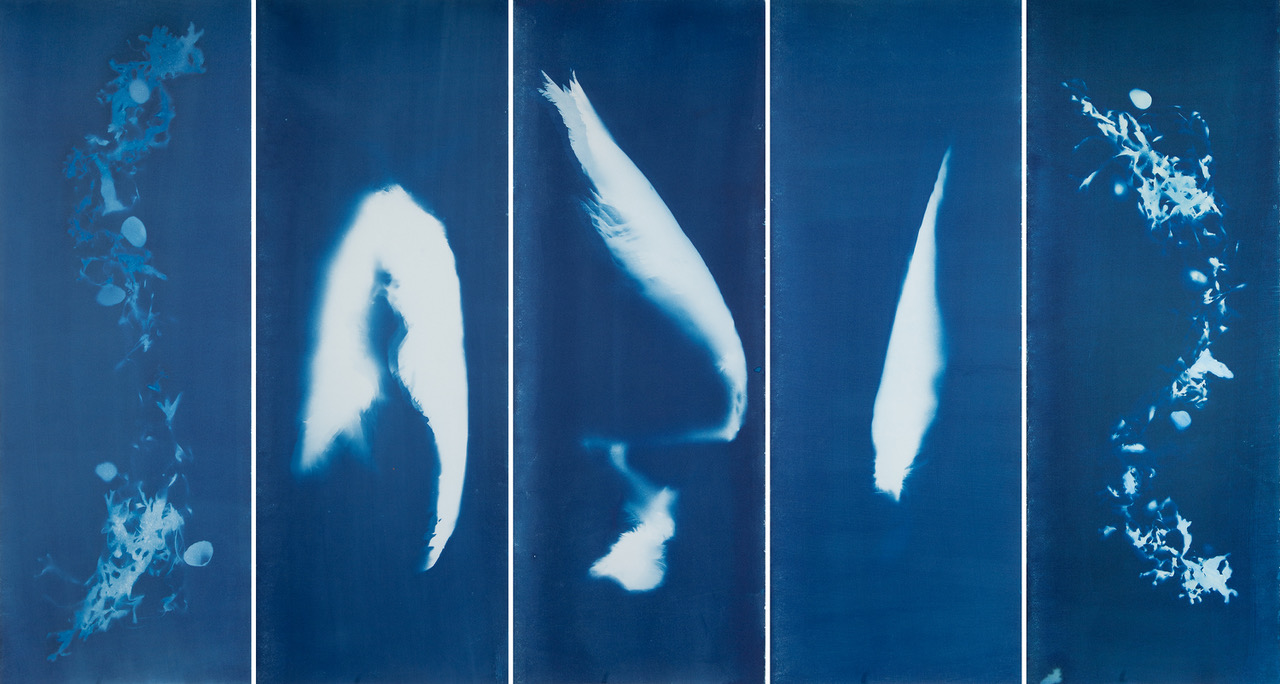

Over email we discussed her current body of work, Endless Forms Most Beautiful, a collection of cyanotypes and large-format black and white photographs.

Janelle Lynch is a New York-based artist whose images reveal an inquiry into themes of connection, presence, and transcendence. She uses an 8×10-inch view camera and 19th-century cameraless processes, and her work is often informed by her training in perceptual drawing and painting.

Janelle’s photographs are in many private and public collections, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the International Center of Photography, New York; and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. She has three monographs published by Radius Books: Los Jardines de México (2010); AIGA award-winning Barcelona (2013), which also features her writings; and Another Way of Looking at Love (2018).

Instagram: @janelle__lynch

Montserrat A. Carty: In your project statement you write beautifully about imagining the unseen. Your work, and this project in particular, feels rooted in a spiritual practice. Is that accurate, and if so can you expand upon that?

Janelle Lynch: My belief in the power of an image to hold the spiritual presence of the being or elements depicted, particularly after direct contact has been made as in the cyanotypes, is rooted in my early life with my grandmother––Nana, who raised me until I was 10 years-old––and a portrait of my grandfather, Nanu. Nanu was my father figure and, as an amateur photographer, the one who introduced me to the medium essentially from birth. His life and death are why I use photography today as my primary medium. A portrait of him, which was made shortly before he died at age 57, when I was just four, hung framed in the living room. I recall frequently witnessing Nana standing in front it talking to Nanu.

Another early life experience illuminates the origin of the concepts that underpin my work in alternative processes. When I was a child, Nana’s bedroom was right across the hall from mine, and I could see a bust of the Virgin Mary and baby Jesus on top of her dresser. Daily, I witnessed Nana’s ritual: she would stand in front of the bust and rest her hand on it. Observing this seeded ideas in my young consciousness about the power of the will to believe; the raw and immediate power of tactile connection; and the potential for inanimate objects to hold and transmit the energy of spiritual essence.

In 2020, my interest in the possibility of communication between the material and the ethereal worlds was growing and its potential was reinforced by Alan Lightman, the physicist, in his book Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine. He explores, through the lens of personal experience and his work as a scientist, the intersection of science and spirituality. He describes a transcendent experience laying on his boat under the starry sky….“I felt a merging with something far larger than myself, a grand and eternal unity, a hint of something absolute,” and he put forth his belief that as beings in a material world, we are capable of experiences that transcend the provable, and that there is, indeed, a spiritual realm to our universe.

In addition to Lightman, my other research references included Spiritualism, a movement predicated upon belief that the soul survived after death and could continue to evolve and to communicate with the living; and the subsequent movement, spirit photography. As is often the case with spiritualist phenomena, the most intense interest in spirit photography has followed periods of war, when victims’ families longed to have one last contact with their loved ones. This was true in the United States after the Civil War and in France after the war of 1870. The millions of deaths during World War I also gave rise to a revival of spirit photography in Europe.

MAC: Can you tell us about your process in creating the cyanotypes and why the medium felt like the right fit for this particular body of work?

JL: In Summer 2018, while I was working with clay at the New York Studio School, a thriving mulberry tree was pruned in the courtyard behind the sculpture studio. I have identified this event—and the drawings or tree rubbings that I made on mulberry paper—as the origin of my work in alternative processes. I took the tree limbs that were unceremoniously severed, and I covered them in paper and made an imprint of them with charcoal and conte crayon. I was interested in making a record of their life as a way of honoring them and in seeing if the paper could hold their energetic essence.

The following year, in 2019, I went into the darkroom with stardust––ashes from the remains of my dearly beloved Golden Retrievers, Gracie and Dollie, who had recently transitioned to the heavens—and plants and tree branches from my former property in the Catskill Mountains where I made Another Way of Looking at Love. I made photograms—direct translations of the objects’ touch and presence made with my touch and presence. I was curious about this other photographic language, liberated from the restraints of representational realism inherent in a camera-made image.

My inclination toward the cyanotype medium, which I started using in 2020—after I lost Gracie and Dollie’s ashes during my move from New York at the height of Covid—was a natural evolution in my practice. Five years after beginning my studies in drawing, painting, and sculpture at the New York Studio School, I was increasingly interested in a fuller experience of authorship in my photographic work—in more direct contact with materials and what might manifest from the synergistic connection between them, my touch, and my imagination. I was liberating myself from the limitations of photographing the physical world. Conceptually, there was an alignment between the medium and my growing interests in imagining what lies beyond visual perception. Formally, the color blue suggests the faraway. As the poet and theologian John O’Donohue said, “Distance loves blue.” Goethe said that rather than coming toward us or hemming us in, blue draws us after it into the distance. With cyanotypes, I could create depictions of the spiritual realm to which I had a growing need to connect. And I became even more excited about the medium as I discovered alchemy’s vital role.

MAC: The three black and white large format photographs in the project are also meditative and exquisite. Can you share about the choice to mix these images with the cyanotypes?

JL: The three images to which you refer, Witness I, 2022, Witness II, 2022, and Witness III, 2022 are records of ephemeral matter—spider webs and dew drops—and a found still life of driftwood in the dunes, all of which were impossible to cyanotype though related to the cyanotypes either in subject matter or in the allusion to the heavens. I worked in black and white as a way of bridging the gap between the material world that is full of color (for most) and the spiritual world that is invisible (to the human eye).

I was photographing consistently during my first residency in Amagansett in Fall 2022. Combining the two mediums felt like it created a more complete representation and a richer visual presentation of my search.

MAC: Endless Forms Most Beautiful was recently exhibited at Flowers Gallery, London. How can people continue to engage with the work?

JL: Flowers has a comprehensive archive of my show on their website, with installation images, a link to an essay written about the work by Martin Barnes, Senior Curator of Photography at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and several reviews about the work. There is also a short video interview of me discussing the work in the gallery.

Flowers will show cyanotypes from Endless Forms Most Beautiful at Paris Photo from November 9-12, 2023.

The filmmaker Mia Allen made a 16-minute documentary about me and my work, Janelle Lynch: Endless Forms Most Beautiful, which premiered in London during my show at Flowers. It includes interviews and footage of my working process in Amagansett. News about US screenings will be posted on janellelynchdoc.net.

From September 13-17, 2023, Welcome to The Salon, a pop-up group show I curated with work from members of The Salon, a collective I lead, will be on view at Foley Gallery in New York City. It includes two works from Endless Forms Most Beautiful. We are also launching the book Welcome to The Salon (Tonal Editions, 2023), which includes five of my cyanotypes in the series From Georgia to Heaven (2020-2022).

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Vaune Trachman: Now IS AlwaysMarch 3rd, 2026

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026