Photographers on Photographers: Jessica Hays in Conversation with Dana Fritz

My time talking with Dana Fritz absolutely flew by. We had the great fortune of meeting each other in Denver this May, after seeing each other’s talks at the national SPE conference. I have admired her work for many years and am so glad to take time to talk with her.

Our conversation touched on several projects, but we really talked about methods of working and life as an artist. We spoke for over two hours and shared so many stories I had quite the task of editing our conversation down to length. Dana is committed to her role as a mentor to her students and modeling a life as an artist and dispensed so much wisdom in our conversation. I hope you’ll enjoy our conversation!

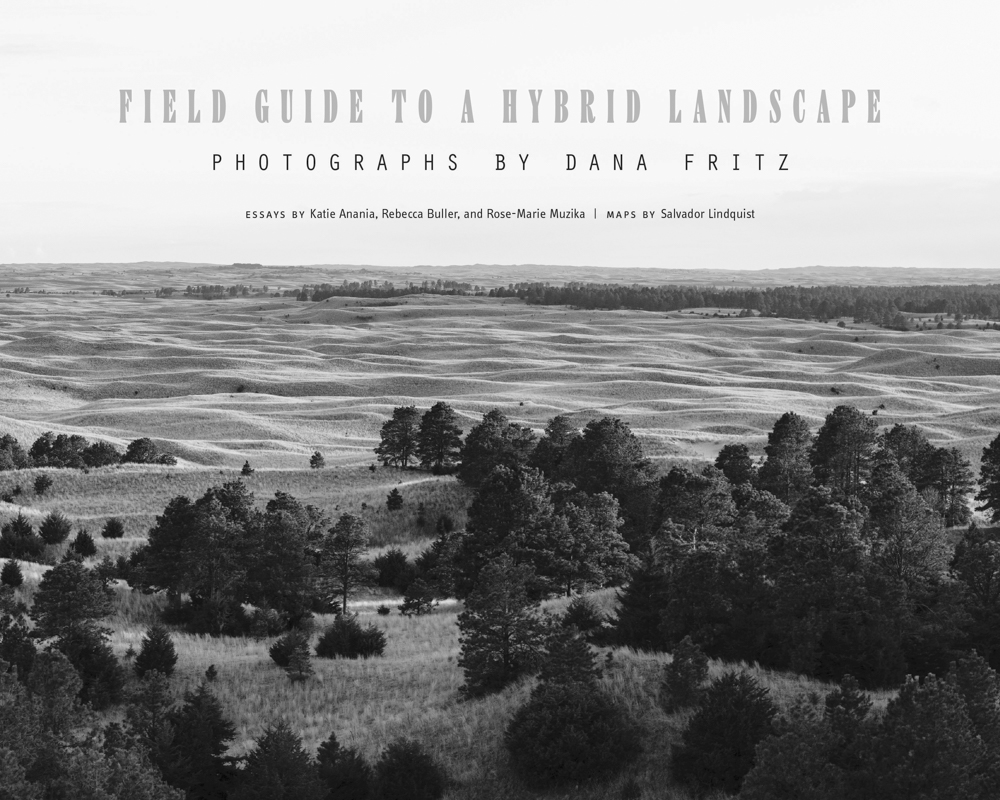

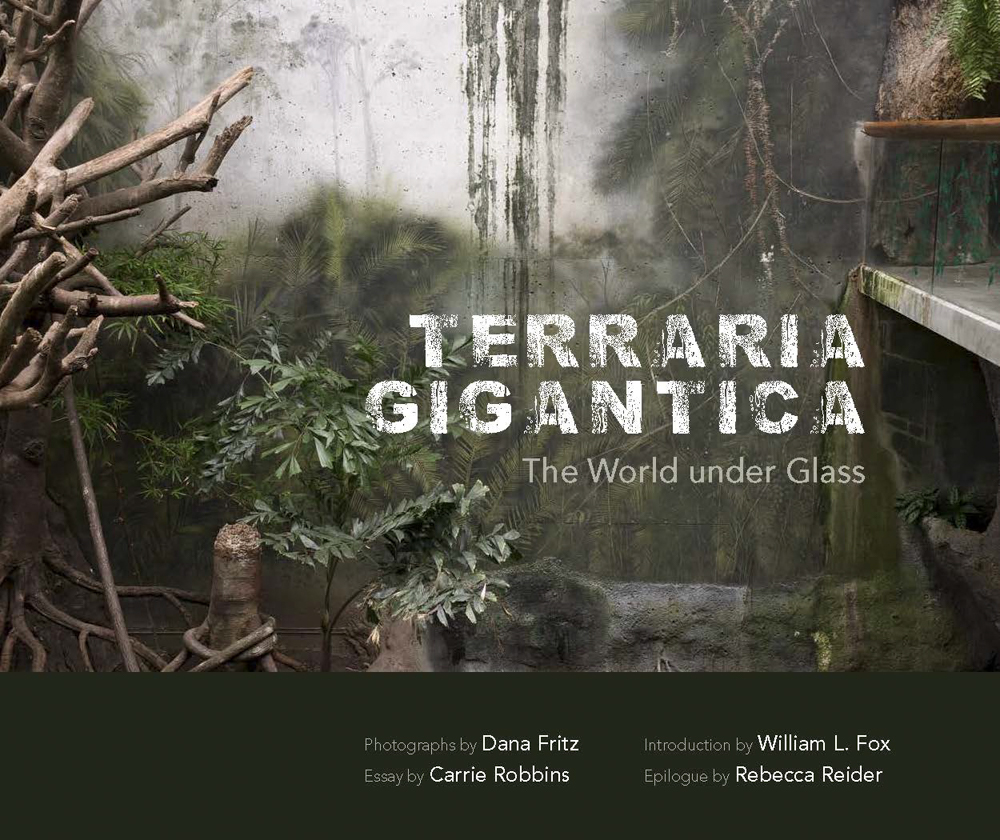

Dana Fritz is Hixson-Lied Professor of Art in the School of Art, Art History & Design at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln where her work in photography examines how humans shape and represent the land. Her honors include an Arizona Commission on the Arts Fellowship, a Rotary Foundation Group Study Exchange to Japan, and the Society for Photographic Education Imagemaker Award. Fritz’s work has been exhibited widely in the U.S. including at the Phoenix Art Museum, Florida State University Museum of Fine Arts, the Griffin Museum of Photography, and the Sheldon Museum of Art. International venues include Museum Belvédère in The Netherlands, Centro de Iniciativas Culturales de la Universidad de Sevilla, in Spain, Château de Villandry in France, and Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, Place M, and Nihonbashi Institute of Contemporary Arts in Japan. Public collections include Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City; Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago; Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Pennsylvania; Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Arizona; the Center for Art + Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art; Yale University’s Beinecke Library; and Museum of Fine Arts Houston’s Hirsch Library. Fritz has been awarded artist residencies at Villa Montalvo in California; Château de Rochefort-en-Terre in France; Biosphere 2 in Arizona; PLAYA in Oregon; and others. University of New Mexico Press published her first monograph, Terraria Gigantica: The World under Glass, in 2017. University of Nebraska Press published Field Guide to a Hybrid Landscape in 2023.

Follow Dana Fritz on Instagram: @danafritzphoto

Jessica Hays: What has your summer research been like so far?

Dana Fritz: Summer is generally restorative for me. I’m always exhausted when May rolls around, and I need the summer to work in the studio and to feel refreshed as a teacher in August. But I just ran out the door and went to Spain right after the end of the semester to participate in an exhibition and a related symposium. I’ve been home in Lincoln, Nebraska for a couple of weeks trying to prepare for my Tallgrass Artist Residency in Kansas. I’m reading and thinking about what I want to do there.

JH: That sounds amazing, how long it the residency?

DF: It’s only 10 days, but I’m excited to have that prairie right out my door.

Speaking of changing locations, going to Chicago must have been a big shock to your system from living and working in Montana. It’s so incredibly different and I think that might be exhilarating at times, but I think it could also be hard on your body, and your mind, and your heart.

JH: Yeah, it was a big shift. I ended up having sort of a hybrid grad school experience, attending the first year online and the last two in person, and that was perfect for me. Western landscapes were more of a setting rather than the subject of the work earlier on. But then there was a wildfire that started right outside my window. That was it for me. I couldn’t look away and really launched into that work.

DF: Well, that makes more sense to me now, how you could have done that work. Travel like that is very difficult in grad school but in your case, it totally worked out.

JH: Yeah, it has helped having a home base here in Montana too. I’m able to photograph really intensively in the summers. Usually when I come back during the academic year to visit, I’m spending a lot of that time photographing as well. Back in Chicago is when I have time to sort things, edit, work through the images I’ve made either in the darkroom or in book format. So I actually think a lot about how Victoria Sambunaris does those massive road trips and makes all work, and then goes back to New York to finish it. That’s kind of how I work too.

DF: Speaking of wildfires, I am chairing a panel on climate change and climate anxiety at the Sheldon Museum of Art in Lincoln this fall in conjunction with the exhibition From Here to the Horizon: Photographs in Honor of Barry Lopez. Marion Belanger has work in the show and is also a panelist. In a zoom conversation that was part of the Environmental Photographers Collective we belong to, Marion mentioned that in her practice as a therapist, climate anxiety is increasingly common.

JH: There’s a lot of growing awareness around climate anxiety in general. When I first started talking about it, and about solastalgia, not very many people were familiar with those ideas. But now, about half of the people I share my work with have an idea of what grief for a landscape or a place is like. It’s so interesting that it’s become so commonplace that we’re developing whole taxonomies and treatment methods because it’s different than other anxieties.

DF: It’s so common, especially among younger people, and that’s so heartbreaking to me. But also understandable.

JH: We’ve gotten started sort of on our own, but I guess for the first ‘official’ question I was wondering if you could talk about a little bit about like your journey into photography, and how you got started.

DF: In a way it just seemed so natural. My mom felt it was really important to photograph our lives. It included things like pictures of the first day of school each year, birthdays, and holidays, so the camera was always around. We had a garden, and my parents were always excited about harvesting seasonal fruits and vegetables so that was pretty influential on me. As a kid I was drawing a lot and even making books about flowers. So, there seems to be a direct link to what I’m doing now. I certainly took art classes as a teenager, and probably as a young child. And I was supported to do it, so I was lucky. I even had a photography class in junior high. My mom stayed at home with my brother and me and it seemed like my dad worked all the time. He was a chemical engineer who designed wastewater treatment systems for coal fired power plants. So his work in connection to the fossil fuel industry gave me the privilege and luxury to be an artist who’s critical of that now.

JH: Yeah, having that sort of understanding very early on.

DF: It’s only in the last several years that I realized the irony of that. But you know, 30 or 40 years ago it was less common to be as critical of coal-fired electrical power. We were all happy to have air conditioning in the summer and cleaner water coming out of the power plants. My dad was a national expert in that.

JH: You’re already talking about kind of these relationships to climate change, in a way, and talking about the fossil fuel industry. I’m thinking about Field Guide and how you were photographing a landscape over several years. It seems like themes of climate change might naturally emerge. Do you see that as a big part of your work, or does it kind of come in later?

DF : I think about this all the time. Regarding climate change, I actually got the idea for Field Guide to a Hybrid Landscape right around the 2016 election, when it was very clear that the United States was going to drop out of any kind of climate agreement. That was, to me, a really pivotal time where the United States needed to be part of a climate agreement, and it was so clear that was just falling apart. I had been traveling very far to make my work, to Japan, England, to Arizona a lot, and I thought I wanted to do something closer to home. I wanted to really understand Nebraska because I am committed to living here.

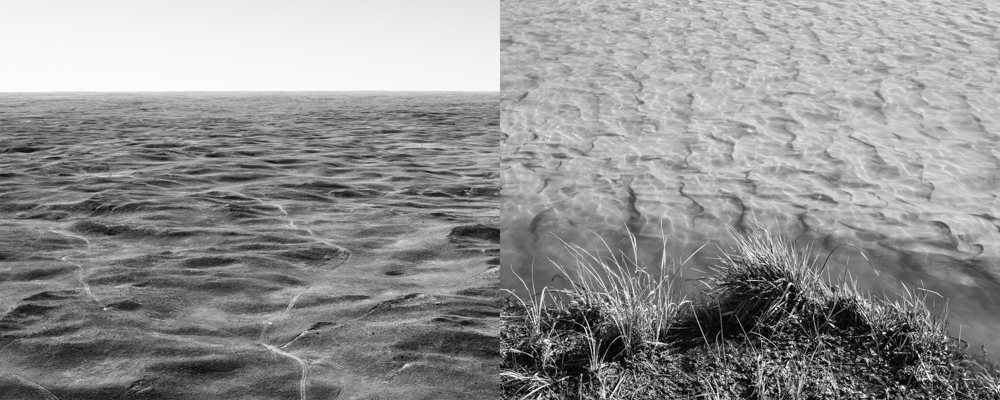

I had been to the hand-planted in forest and thought it was a weird kind of novelty, but I didn’t go too deeply into it. But then I started thinking about why it was there, what kind of thinking made that possible as a proposal, and then as something that could be enacted. That’s where I got really interested in it. I was fascinated by it as a novel ecology, a hybrid place, something that wouldn’t occur without large-scale human intervention.

Once I started reading, I found out that the forest was planted to change the local climate, which was an interesting idea. I mean, we now know how important it is to plant trees in urban areas, because it literally will change the local climate, the temperature, and it will be cooler and safer for people in summer. The forest was proposed to mitigate wind and evaporation of moisture in the semi-arid climate of the Nebraska Sandhills, but this grassland ecosystem was seen to have less value than a forest. It was considered “unproductive.”

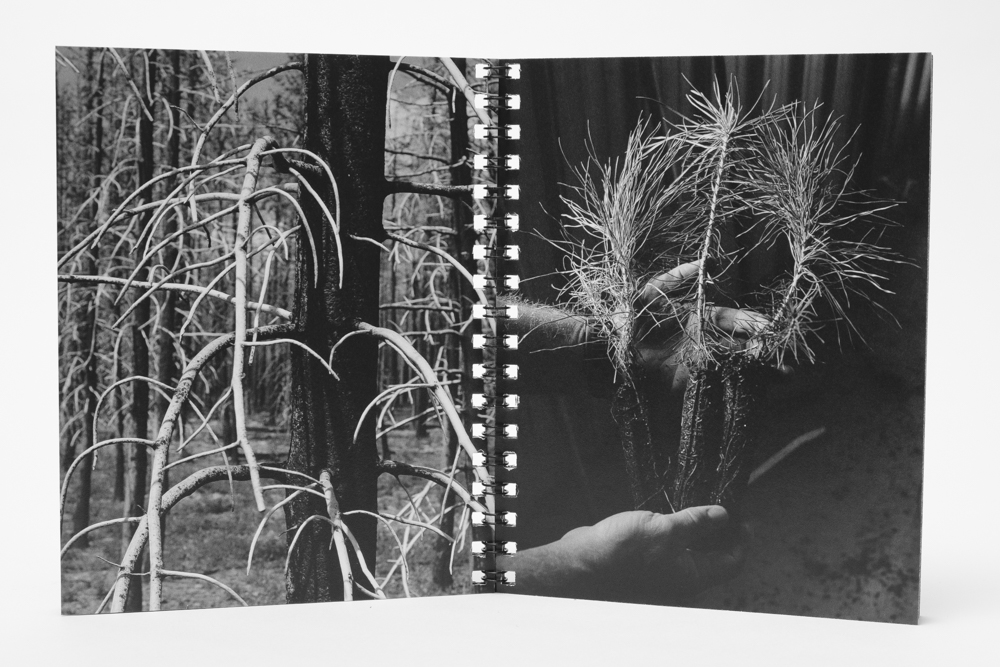

DF: The first federal tree nursery was established there to grow seedlings for the new forest and for plains homesteads, but large scale-tree planting ended in the forest in the mid 1960’s. The nursery now grows most of its seedlings to replace trees in National Forests that have suffered from climate change-driven catastrophic fires or beetle infestations. So, in my book, the story of the hand-planted forest is related to evolving ideas about climate change.

In Nebraska there have always been fires in the grasslands and forests both from human and non-human causes because that is a normal part of these ecosystems. Many fires are from lightning strikes, and they often burn out on their own. But in 2022, after my finished book was in press, there was a big fire in May, which is usually a wet time, and then there was an enormous fire in October that burned the fire tower, the historic 4H camp, and a large part of the hand-planted forest and grasslands as well as some nearby ranch land. But that same summer there were fires all over Nebraska that coincided with a terrible drought. There was even a fire evacuation in my county in eastern Nebraska. I have never heard of so many fires in 25 years of living here. Where I live in Lincoln fire season was not front of mind before 2020, but now we have much more of an awareness of it for both smoke and actual nearby fire danger. And where you’re from, fire season is any time there isn’t snow on the ground, right?

JH: Yes, it’s much longer now. It used to be in August or maybe September there would be fire somewhere, and get a little smoky, and then it would be over after a week or two. And now there’s a fire in May, in June, July, August, September, and so on, and sometimes its smoky all summer. There’s a town about two hours from my hometown that was incinerated by a downed power line in early December, when there’s supposed to be 2 feet of snow on the ground in that part of the state. I’m sure you probably heard some of the news stories about the wildfires that started outside of Boulder right around New Year’s—which is way outside of our idea of wildfire season—and it burned down 600 homes.

DF: That’s also so obviously related to drought. It sounds like your new project. This summer (2023) we are in extreme drought here in my part of Nebraska, and all of the state was in a really bad drought last year. Lincoln has voluntary water restrictions right now. We converted a huge part of our yard to prairie, but it needs water to establish the deep roots that will protect it from future drought.

JH: You started to touch on it a little bit, but I was interested in how Field Guide is based in the local/regionally nearby geography. Some of your other projects are much further afield. I am curious about how you view your practice in relationship to travel. How does location have an influence on how you approach making pictures?

DF: I think that I go to a place because I’m interested in that location, and I’m going to make work there or about that place. I’m not somebody who carries my camera all the time, except for my phone with a camera that I use for visual notes.

I need to get back out to the hand planted forest. I thought I was finished working there but the recent fires really transformed so much of that land, and I realized I am invested in its resilience. I want to know what is coming back. There’s no analog for this place, so the only way to find out what happens there is to go and witness it. Other locations that have become important are where the trees from the nursery are planted in National Forests on the Colorado and Wyoming front range of the Rockies. You can see my work about this in a story map that became an artist book called Re: forest that was commissioned by Platte Basin Timelapse.

It was a little bit of an anomaly for me since I do most of my work in the “west,”, but I had an opportunity to do a residency in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan in the Huron Mountain Wildlife Foundation land in 2022. I kind of dropped in like an alien from the Great Plains into the North Woods. And fortunately, I had a human field guide, forest ecologist Rose-Marie Muzika who does research there. I made an artist book about what visually and conceptually stood out to me, and that happened to be the way birch trees don’t decompose quickly. It’s about site, but it’s also about the ecology of site.

And that’s why I’m excited to go to the tallgrass prairie, because of the prairie ecology and plant communities. That field of study that was developed at the University of Nebraska about a hundred years ago.

I don’t know if that answers your question about travel, though. I went to Japan a lot to teach, and I learned as much as I could about the plants and how the land was shaped by people. I obsessively studied all the plants in Arizona, preparing to live there during grad school. I’ve always been very interested in the land, but I actually want to travel less to make my work now.

JH: You began talking a bit about your work in Japan and Arizona, where you combine negatives into longer compositions. I’m curious when this form came into the project. Was it in the beginning or later?

DF: That’s a great question. The Views Removed prints were inspired by studying Japanese art and being exposed to it so much through teaching in my study abroad class. I was thinking about negative space and form, and how form was so important in Japanese gardens, bonsai, and painting. I was thinking about how we see and represent the land in paintings and photographs, in eastern and western traditions. That form came fairly early in the project from being frustrated with my ability to produce, with a single negative, the kind of space I wanted to depict in a traditional print. All of those prints are imagined landscapes, made from two or more negatives. The longer format made it possible to make these multiple exposures and still leave negative space.

JH: Do you preconceive your projects in their final form, i.e. as books or prints? Or does that happen later?

DF: For Terraria Gigantica, the idea of the book was definitely later. I imagined the work first as exhibition prints, then later as a book when it was finished and when I better understood the ideas. But having previously published a book, it didn’t take me very long at all to realize that the Field Guide also had to be a book, because it was too complicated to completely convey in an exhibition. Even so, I worked very hard to organize this large exhibition in a way that helps communicate the forces that shaped the hybrid landscape. The book is a more complete way to understand it. You can just look at pictures, or you can read the essays and study the maps and timeline. There’s a lot of information.

JH: I love books for a similar reason—you can do so many things with them and include so many different types of visuals and texts when it is well done.

DF: Yeah! And that’s why I made a book with the Re: forest project, too. Because I really wanted the page spreads to juxtapose the more human and less human pictures, and to envelope them in these archival photographs on the cover. All of that is possible in a book, and just less possible in an exhibition because of the way people move through a space.

JH: Your book, Field Guide to a Hybrid Landscape, was recently published. Do you have any new projects on the horizon that you’d like to talk about? Or is it all the top secret right now.

DF: No, nothing’s top secret, because everything takes so long to develop. I’ll be working with my colleagues in the School of Natural Resources who are studying post-fire resilience in the hand-planted forest. I’m learning a lot from them and I’m excited to see how our collaboration unfolds. And I’ll be working on something related to the tallgrass prairie, my local ecoregion. But there’s so little of it left, probably 4% of what was here before European settlement. There are small patches of it nearby, and the idea of understanding what’s right around me, or I should say, what was here in abundance, is really fascinating. I’m interested in the ecology and the history. Tallgrass prairies are pretty amazing for carbon sequestration, and they’re resilient in the face of nearly everything but the plow.

But what will I make? It probably won’t be a bunch of framed prints that I have to find room for in my office because I can’t walk around the crates right now! At this point in my life, I’m really thinking differently about traditional big solo exhibitions. That’s another kind of conundrum that has to do with environmental issues and materials use. I’m struggling with how to present these ideas. Because, really, the ideas motivate me and how to share them is my challenge.

I also think that the pace I was working at for the last couple of years is unsustainable, and I need to get serious about that.

JH: Do you have any thoughts on maintaining and developing a photographic practice? I really identify with what you just said about pacing and working in a way that’s sustainable long term. Things can get unsustainable so quickly, especially with the sort of migratory nature of early academic careers. What advice do you have to keep your practice and other commitments paced at a sustainable level?

DF: You must catch your breath. You must understand that you need to find your footing when you get to the next place, and you’re likely going to feel like somebody pulled the rug out from under you. Hopefully, you’re going to have good mentorship wherever you go. Don’t be afraid to ask a colleague to talk about things over coffee. Don’t hesitate to ask, because other people are probably busy, and it may not be top of mind to make sure that Jessica is okay. But you need to find your people. Don’t wait. Find your people in your community, and they might be in surprising places.

My best advice solicited or not, is that you need a studio day during the academic year. My grad students have told me this is one of the best things that I modeled for them, which was to protect my studio day. If possible, it should be Monday. Stuff just piles up, and if your studio day is Thursday, you don’t really get it, because there are too many emails, tasks, and meetings. If you just say Monday is my day, when your life is in balance, you can start on Sunday, and you get two days. At some point everybody gets used to it. They realize that if you don’t protect your studio day, you won’t get anything done. So that’s my best advice. Studio day on Monday.

JH: These hours have really flown by! Thank you for taking time to sit down and talk with me!

DF: It was wonderful. Do you expect to be at the next SPE conference in St. Louis?

JH: Yes, I’m planning on it!

DF: Great! I think SPE has been really important in my career. So maybe I’ll see you in St. Louis! I already gave you all my advice, but I think SPE is working hard on trying to prepare mentorship opportunities for early career faculty. So tune into that because you’ll have a lot of questions and probably want more advice after you have some more time in your job.

JH: Thanks so much!

Jessica Hays is a photographer, alternative process printmaker, and artist based in Montana and Chicago. Her intimate work draws on personal experience to communicate ubiquitous human experiences, tackling topics like mental health, landscape change, and loss. Grounded in the American west, she explores relationships between people, places, and experiences of being deeply connected to ones surroundings. Hays’ work aims to explore interactions between psychology and climate change, investigating how landscapes effect the human psyche from trauma to restoration. Hays works in a variety of processes including pigment printing, handmade artist books, video, and historic and experimental photo processes. She has lectured on topics of mental health, climate issues, and contemporary photography at conferences, mental health summits, and as a guest speaker in classrooms. Her work is shown nationally and internationally in galleries as museums, including The Holter Museum of Art, Filter Photo, Old Main Gallery, Blue Sky Gallery, Huaguang Photography Art Museum, and Candela Gallery among others. Hays’ work has been published in a variety of magazines and textbooks, including The Experimental Darkroom, Oregon Humanities Magazine, and the Hand Magazine among others. Her work is held in several public and private collections in the US and Canada. Hays received her MFA in Photography from Columbia College Chicago, and earned a BA in Film and Photography and a BA in Environmental Studies concurrently at Montana State University. She is currently a Visiting Lecturer in Photography and Media Arts at the University of Tennessee Chattanooga. She was recently recognized as a Critical Mass Finalist, shortlisted for the BarTur Environmental Award, and named a 2023 Chulitna Artist Fellow.

Follow Jessica Hays on Instagram: @jess_the_photographer

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Jason Lindsey in Conversation with Areca RoeApril 21st, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: J Wren Supak in Conversation with Ryan ParkerApril 20th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Josh Hobson in Conversation with Kes EfstathiouApril 19th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Leonor Jurado in Conversation with Jessica HaysApril 18th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Sarah Knobel in Conversation with Jamie HouseApril 17th, 2024