Artists of Türkiye: Sirkhane Darkroom

This week artist and curator Mehves Lelic shares the work of artists and/or organizations from the photography community in Türkiye (Turkey). Today she features Sirkhane Darkroom, a nonprofit organization led by artist Salih Serbest that aims to teach children in Turkey, Syria and Iraq analog photography skills and gives them a chance to explore their world through the medium. Originally from Kobane, Serbest was inspired to start the project after meeting people displaced by the Syrian war and hearing their stories in the early 2011s. He launched the project in 2018 out of a mobile darkroom. Serbest instructs the students to use the camera as a tool to get to know themselves better and appreciate and depict the beauty and dignity in their environment, while providing them a creative outlet.

This post is dedicated to Serbest and his students, whose photographs demonstrate what excites and intrigues them rather than define them by the immeasurable burden war places on children. Sirkhane Darkroom uses analog photography as a powerful art therapy tool and gives children creative freedom – something the developed world may take for granted. Children anywhere in the world are forced to grow up as soon as a violent or negative life-changing event takes place, such as war, poverty, or lack of access to resources. Working with refugees and local children alike, Sirkhane Darkroom aims to enrich the children’s lives, meanwhile giving them a tool to process their grief, if they choose to do so.

Instagram: @sirkhanedarkroom

Instagram: @serbestsalih_

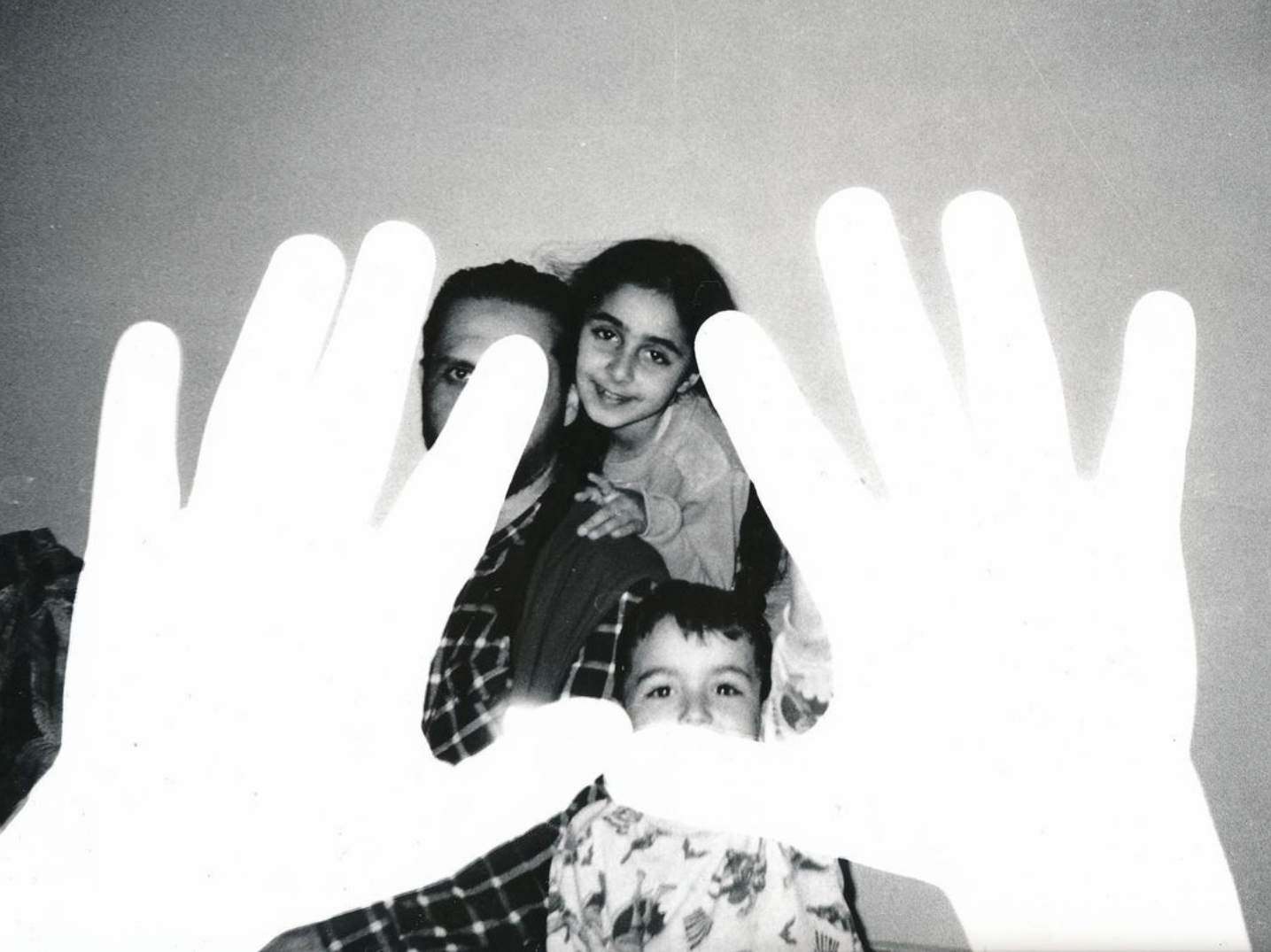

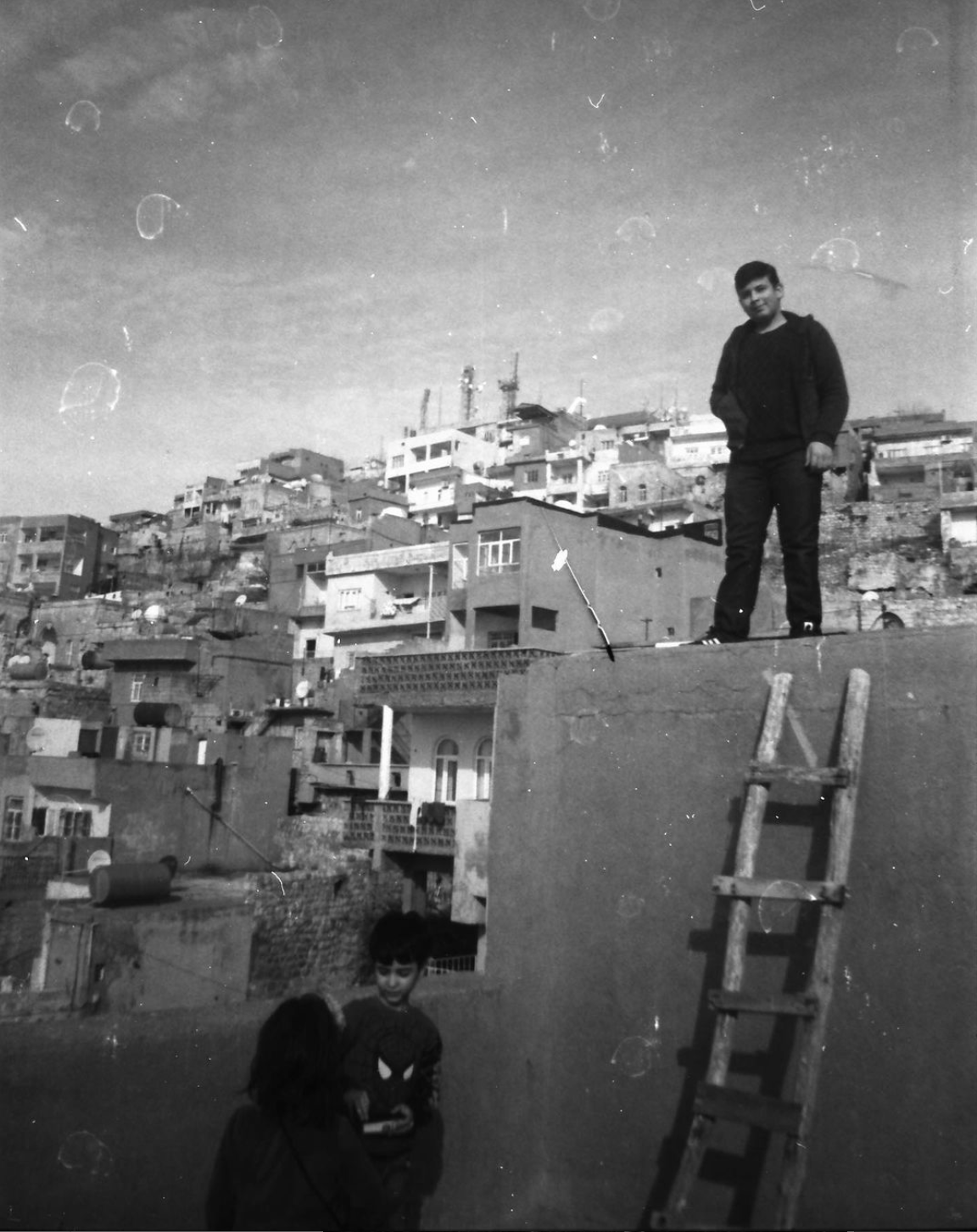

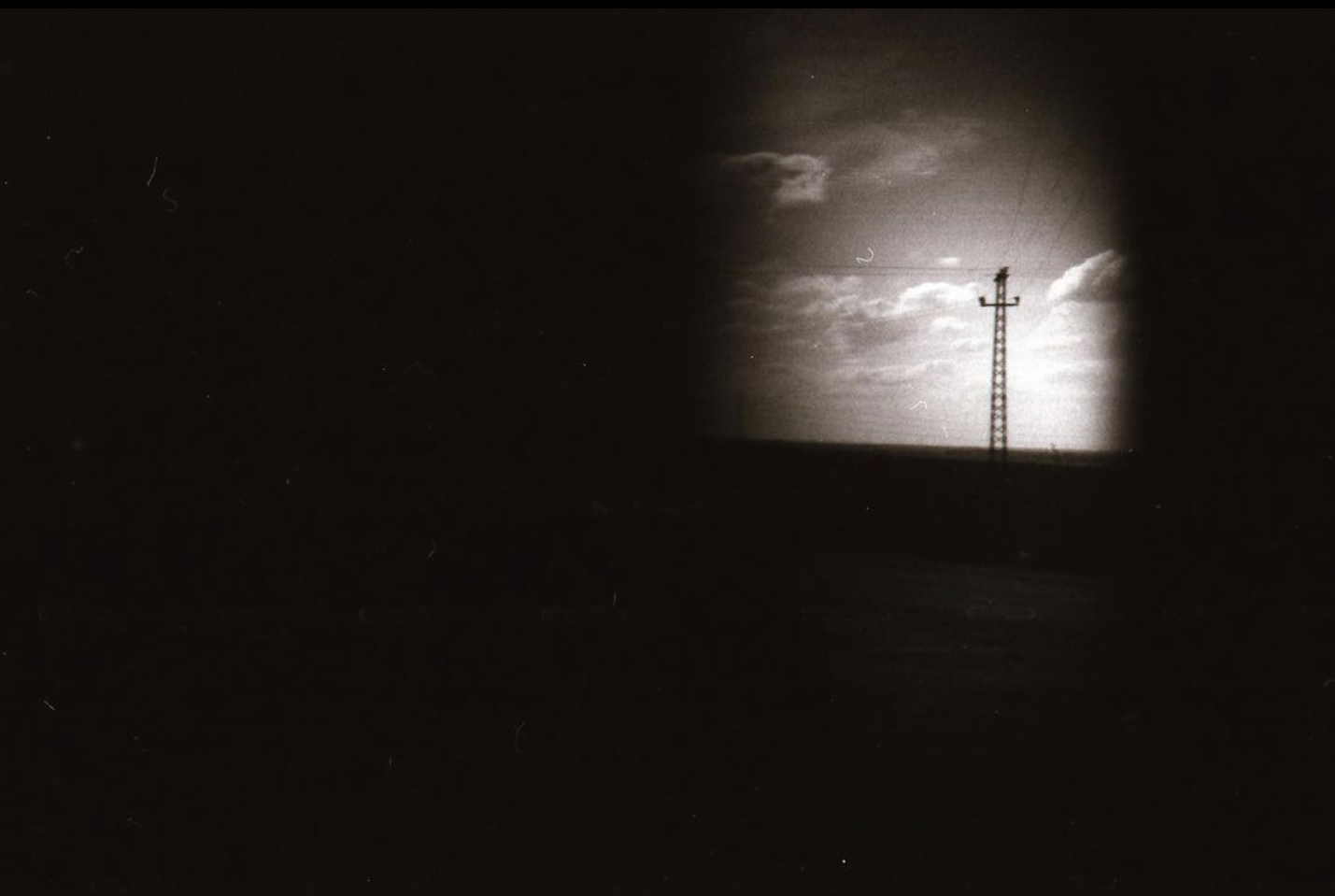

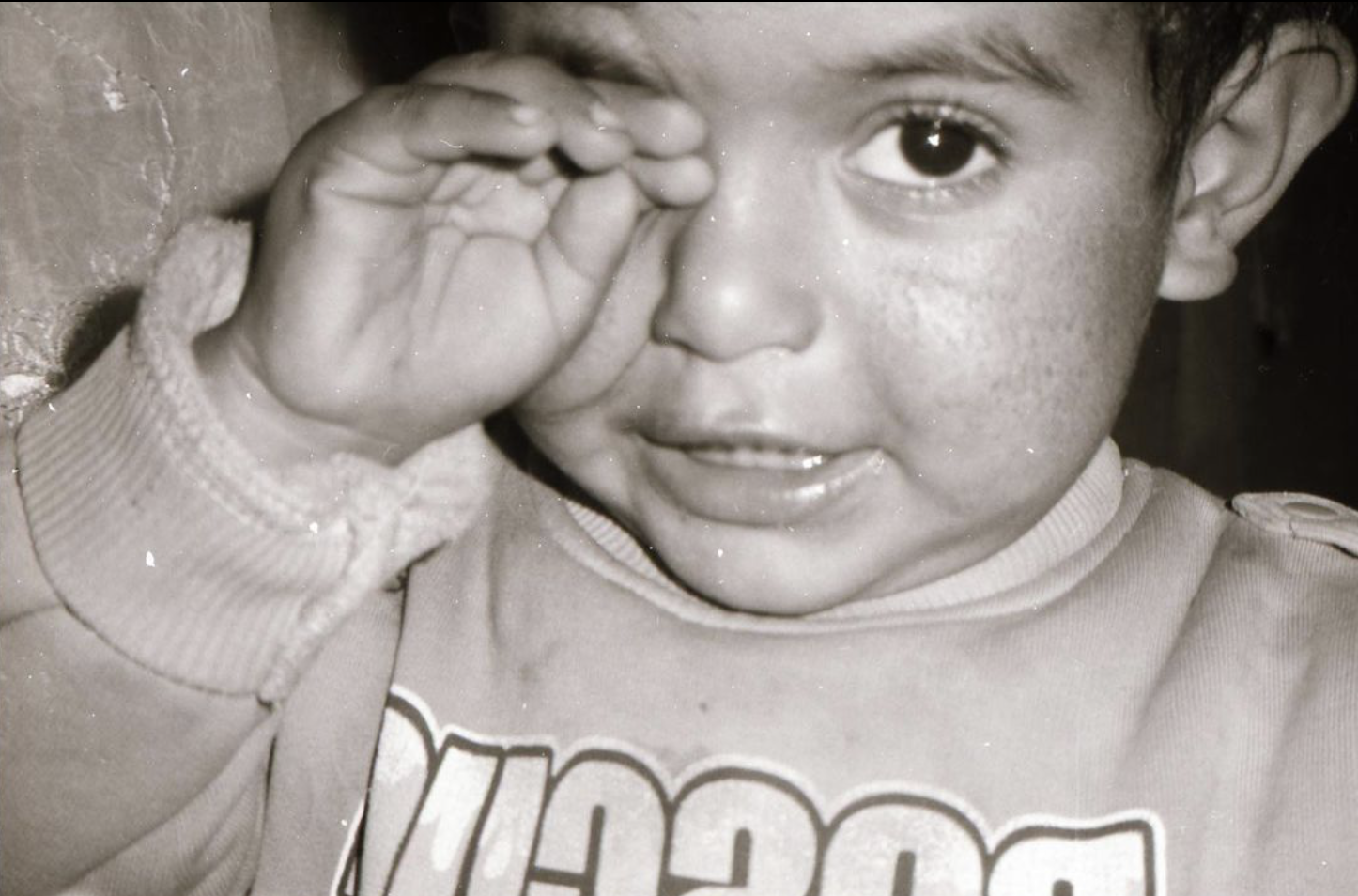

Analog photography is an apt medium for the goal, as the tactility of working with film is a meditative process that gives children a sense of accomplishment and skill. Meanwhile, putting themselves, their environment, and their families in front of the camera and presenting everyday scenes in artistic and creative contexts help the children develop critical thinking skills and allows them to highlight the exciting, the interesting, and even the mundane. In some of the images, the subjects – other children or sometimes families – are delighted to be photographed. Posing with friends, family, and pets, or taking self-portraits, the children’s photographs are characterized by exuberance. Some of the images take on a new life as they pass through the analog process: a landscape, darkened perhaps by a student of exposure or chemistry, takes on an otherworldly, interpretative beauty. Serbest starts by giving each student their own roll of film. The finite number of exposures creates an interesting economy that allows the children to reflect on what about their daily life they will place in front of the lens. Serbest is also experimenting with longer-term loans for older children.

The photographs show the viewer so much about the inner world of children: we get to see candid, idle moments that only friends would witness, that acknowledge the starkness of war and displacement without romanticizing its simplicity. Some of the images show whimsical, performative moments where children dance, stick out their tongues, or get really close to the camera. In others, the photographers treat us to casual observations from their lives that become meaningful due to the surrounding circumstances. Recording their families and community in particular give the children a chance to preserve their heritage and strengthen familial and friendship bonds, as displacement may sometimes threaten refugees’ access to their own heritage.

Critically, Serbest’s project is one of decolonization: the geography he and the children work in has been a silent and misrepresented subject of the Orientalist lens. Often, explorers, landscape photographers, and studio photographers alike would picture the Middle East in ways that served existing exotic tropes. Visual surveys and historic monuments would picture lands devoid of their own people, while photographs of people would seek to enforce broad categorical “types” by occupation, ethnicity, or gender. Cameras rarely ended up in the hands of the people who lived there, who might have inserted more nuance and diversity to the images. Even today, the heritage of Orientalism remains in common depictions of this region – Southeastern Turkey and Northern Syria and Iraq are broadly generalized as perennial conflict zones using colonial vocabulary. So, Serbest offers an undeniably crucial perspective into the area that subverts both the long and damaging heritage of the Western gave and offers a type of photographic work that does not seek to simplistically picture the ambiguous other. Instead, the children make photographs that candidly demonstrate what life is like for them, unmitigated by the baggage of expectation.

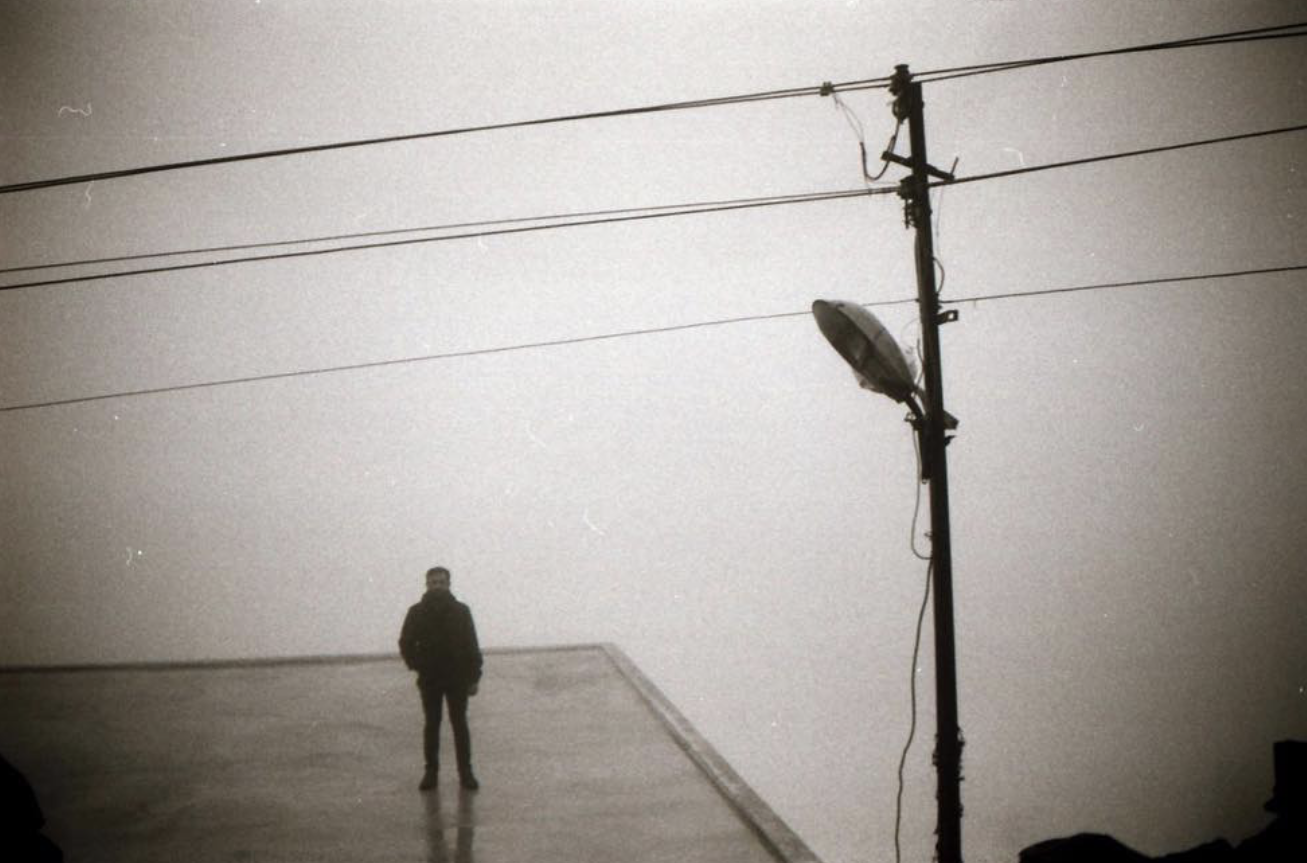

Serbest’s own work is fascinating in its own right – a photojournalist with a degree from the University of Aleppo, his natural curiosity and formal discipline defines his images. These days, he has turned his lens to the children of Sirkhane Darkroom, documenting their journey exploring the medium of photography and making sense of the world. He likes to juxtapose distant figures with the sparse built environment that is characteristic of rural Turkey, especially the southeast. His portraits are dramatic, allowing the viewer a close, candid commune.

One of my favorite images from Serbest’s posts is a portrait of a tween boy, seen through blades of grass. 13-year-old Abdullah made the photograph to explore what humans looked like through the lens of other living things. The empathetic theme, coupled with the broad focus in the image that highlights the individuality of the subject among a rich pattern of the ordinary, is an ode to perseverance.

Mehves Lelic is an Istanbul-born artist, curator and educator based on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. In her work she ponders modernity and heritage, belonging, and the resulting relationship with the environment. She is an Assistant Professor of Art and Art History and the Director of Mosely Gallery at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore. She holds an MFA from Bard College and a BA from the University of Chicago.

Lelic’s photographic work has been exhibited internationally in venues such as the Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art, Rotterdam Photo Festival, PhotoNOLA, Filter Photo Chicago, the Ogden Museum, Institute of Contemporary Art Baltimore, Cosmos Arles France, the Photographers’ Gallery Istanbul, and others. Her work has been published in the National Geographic, GEO Magazine, Ain’t Bad, Lenscratch, C41, Aesthetica and Der Greif. She has been awarded the National Geographic Expeditions Council Grant, the City of Chicago Individual Artists’ Award, the Turkish Cultural Foundation Cultural Exchange Fellowship, the Association of Art Museum Curators (AAMC) Conference Fellowship, and the ArtTable Faith Flanagan Fellowship.

Lelic previously served as Curator and the Head of the Curatorial Department at the Academy Art Museum in Easton, Maryland and has curated and organized over 20 exhibitions, including Spatial Reckoning: Morandi, Picasso, and Villon (2023); Laura Letinsky: No More Than It Should Be (2023); Marty Two Bulls, Jr.: Dominion (2023); In Praise of Shadows: Jun’ichiro Tanizaki and Modern and Contemporary Works (2023); Mary Cassatt: Labor and Leisure (2023); Fickle Mirror: Dialogues in Self-Portraiture (2022); Jackie Milad: Vestige (2022); Norma Morgan: Enchanted World (2022); The Movable Image: Video Art by Collis/Donadio, Shala Miller, and Rachel Schmidt (2022); Hoesy Corona: Terrestrial Caravan (2022); and On Water (2019).

Instagram: @mehveslelic/

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Vaune Trachman: Now IS AlwaysMarch 3rd, 2026

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026