Holly Roberts: Storyteller

The Museum of Photographic Arts at The San Diego Museum of Art (MOPA@SDMA) recently opened Storyteller: Work by Holly Roberts. The exhibition runs through August 18, 2024. I have been a long time fan of Holly Roberts and her amazing work. I was thrilled to be teaching for a week in San Diego through the Los Angeles Center of Photography and that proximity allowed me to spend significant time with her new exhibition. To walk the galleries, each filled with powerful and whimsical expression, was thrilling. With a strong connection to nature, both human and animal, Holly Roberts has explored her rich and varied inner world. She was an early experimenter in mixing paint and photography, transforming shapes, and applying textured surfaces, and she remains a force in expanding the medium of photography. Driven by inner terrors, Roberts’ art is a symbolic reflection of her life and the imperfections in the world around her. The exhibition is accompanied by a full-color catalogue available for purchase in the MOPA@SDMA Store. Following the exhibition, the nearly 60 works featured in the exhibition will be donated to the Museum’s permanent collection.

An interview with the artist follows.

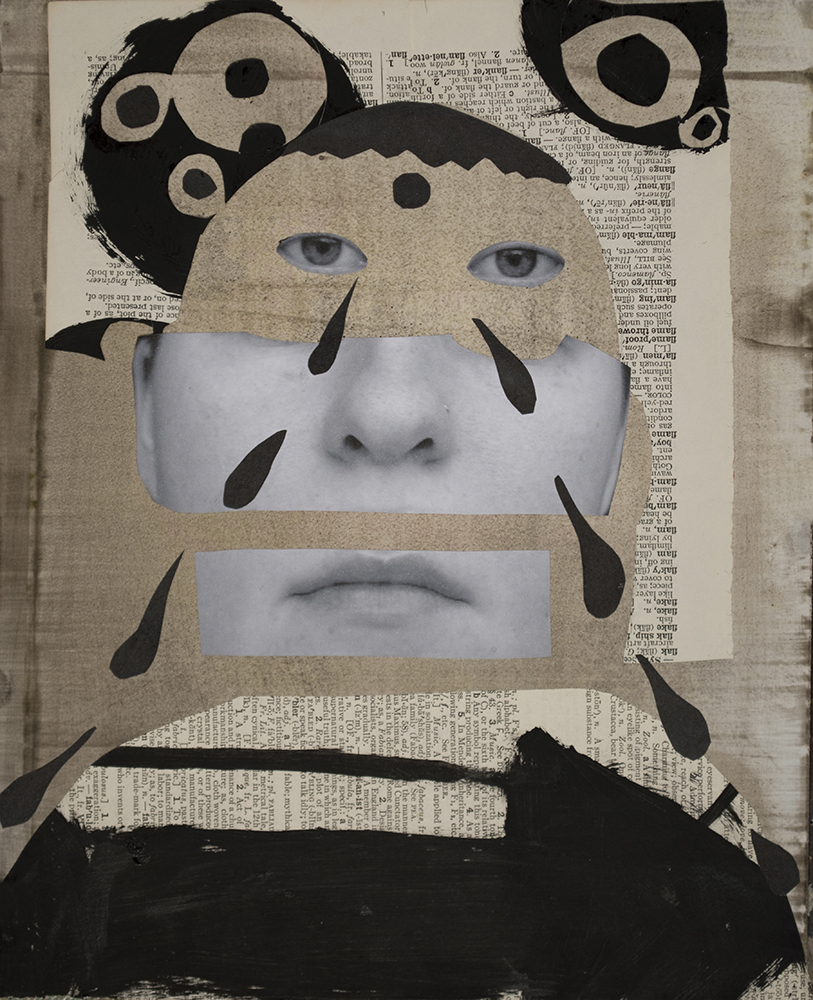

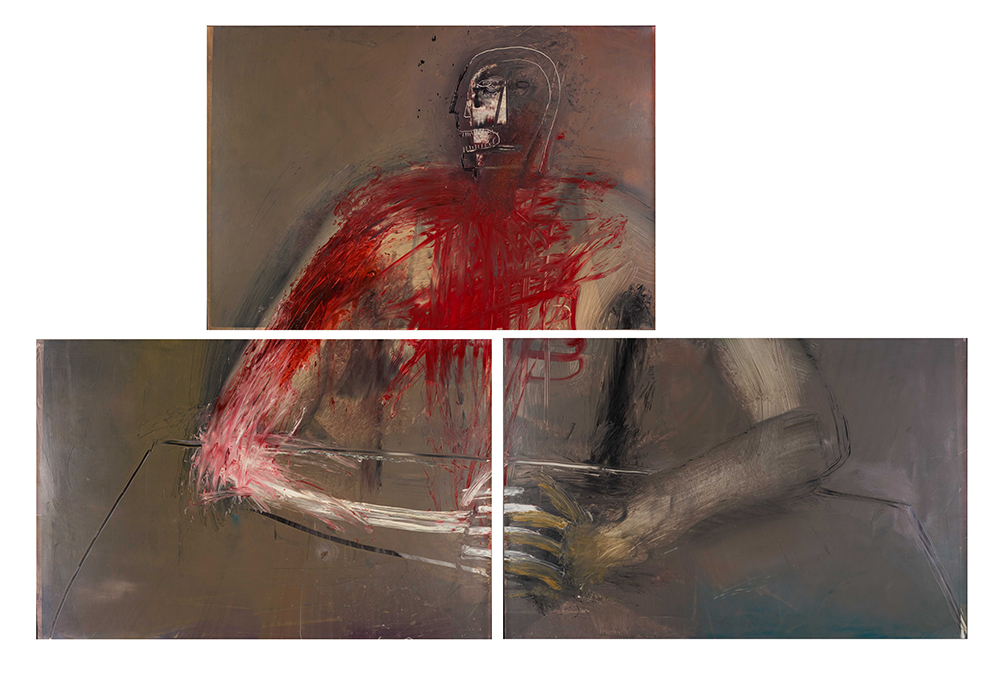

Holly Roberts’ first national exposure came in 1989 with the publication of the monograph, Holly Roberts, from the Untitled Series published by the Friends of Photography. Although her work has always been based on the photograph the inclusion of paint made it a distinct entity. As David Featherstone wrote in his introduction to the monograph, “Roberts is a painter, yet it is the photograph underlying the paint, even when it can scarcely be seen, that gives the work its intriguing, mysterious power. Drawing from the iconography of primitive art, particularly that of the Native American, Mexican and Hispanic cultures of the Southwest, where she lives, she creates paintings that address a broad range of human emotions. While it is Roberts’ evolving interaction with the photograph that takes her to her finished work, it is the existence of the underlying photographic image—even when it is obscured by paint—that gives the work its powerful qualities and sets up the emotional challenge for the viewer”.

Mary Statzer, Curator of Prints and Photographs at the University of New Mexico Art Museum has written, “Holly Roberts contribution to the field of photography is without question. Her work has been added to the canon of experimental ‘creative’ photography in authoritative books on the subject for good reason. Few artists have so successfully combined photography and painting–seamlessly and to great effect–placing the imagined and the ‘real’ on equal footing to describe both lived experiences as well as psychological states and emotion.”

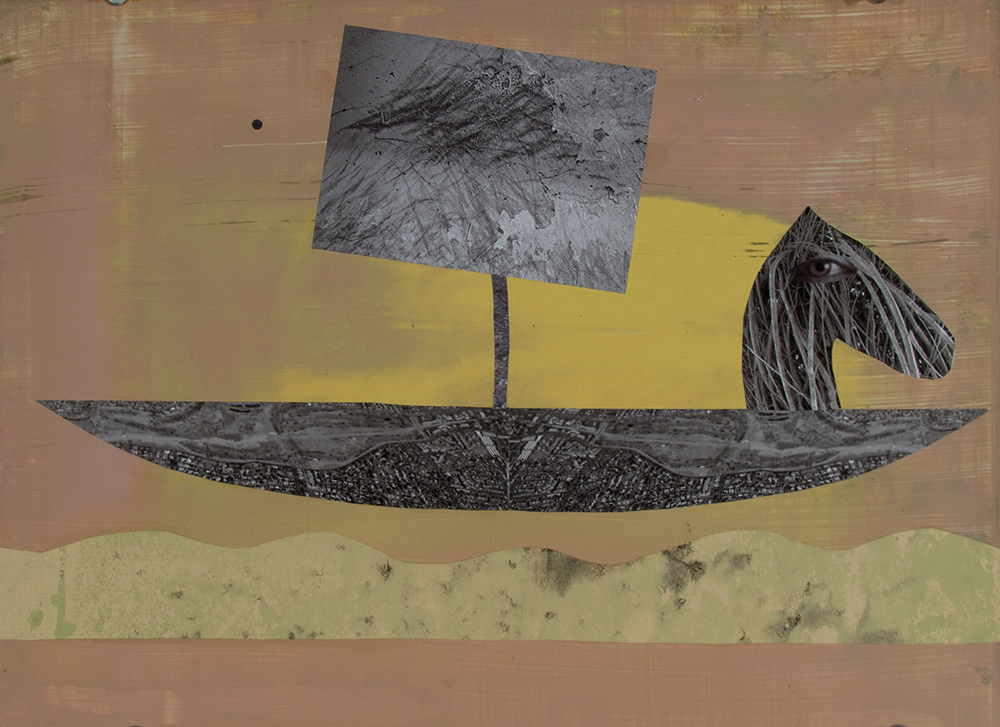

Her work has continued to evolve, but she has reversed her original process of heavily overpainting the black and white silver print. She now works on top of a painted surface, developing a narrative scene with her lexicon of collaged photographic elements. Where earlier pieces reflected psychological or emotional undercurrents, newer works make use of familiar or iconic stories, still with a strong psychological undercurrent, but, as well, addressing tougher questions about Man’s effect on the land and the animals that inhabit it, a dark sense of humor running throughout.

Awarded two NEA individual artist’s grants, as well as the Ferguson Grant from the friends of Photography, Roberts work has been shown extensively both internationally and nationally. Nazraeli Press published Holly Roberts: Works 1989-1999, and in 2009 Holly Roberts: Works 2000-2009. The Griffin Museum of Photography in Winchester, Massachusetts published an extensive catalog of her work in 2018 to accompany her retrospective exhibit at the Museum

She has been published in numerous articles years including “Photography and Art: Interactions Since 1946”, Kathleen Gauss and Andrew Grundberg, Los Angeles County Museum of Art: six books about the photographic process by Robert Hirsch: “The Book of Alternative Photographic Process,” Christopher James, Delmar Cengage Learning, Second Editon:”Beauty and the Best: The Animal in Photography”, Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego, Ca: “New Dimensions in Photo Processes: A Step-by-Step Manual for Alternative Techniques”, Laura Blacklow, revised and expanded 5th edition, 2018, Focal Press, an imprint of Taylor & Francis/Routledge Publishing: “Defining Eye: “Women Photographers of the 20th Century”, Olivia Lahs-Gonzales and Lucy Lippard, The Saint Louis Art Museum: and “Photography: New Mexico”, curated by Tom Barrow, Fresco Fine Art Publications

A dedicated teacher as well as a prolific artist, she has had a profound effect on a community of artists around the country. She continues to live and work in the Southwest. In 2024, Roberts will have a retrospective at The Museum of Photographic Art in San Diego(MOPA), and is planning a monograph of her work to accompany the exhibit.

Instagram @hollyrobertsstudio/

I start all my work by painting abstractly, paintings which will then become the foundation of each finished image. When I started using photographs 40 years ago, I painted directly on their surfaces with oil paints, obscuring the photograph below, then wiping away the wet paint to reveal bits and pieces of the photo underneath. In 2004, I changed that approach and reversed the process, still using the paint abstractly to begin, but now adhering photographs or other materials directly onto the painted surface.

Once I start forming the images, I select from my (bottomless) collection of photographs and assorted material to tell a story. The story unfolds as I work, and is only revealed to me bit by bit. This process is much like following a trail of bread crumbs with no idea of a destination until, at long last, I arrive. What has resulted is a wide variety of images, each with their own story. Because the photographs I use are all my own, there is a deep personal connection to each image as it emerges. Animals, people, and people as animals become the vehicles that portray complicated relationships along with the daily fears, joys, and anxieties of being alive in the world today.

My blending of subjective and objective reality generates a wide-ranging and complex interpretation of my subject matter. Functioning almost as a visual psychoanalyst, I create images that evoke an interior state of consciousness and grapple with a subject beyond its external structure. It is a process that probes other ways of knowing our world based on lived experiences. In searching for deeper meanings through my images, those images become metaphors for that which we cannot know but still sense as truths. – Holly Roberts

Tell us about your growing up and what brought you to photography.

I grew up outside of Santa Fe in a rural neighborhood. We always had lots of animals, plus the wild ones that lived around us(snakes, coyotes, owls etc.), so I think that set up an early precedent for me about animals being in and of my life. I can remember getting my first camera at around 9 or 10 and taking pictures of our dog Robby, and I remember seeing one that was especially nice and trying to figure out why that was so. That was probably what first brought me to photography, that seeing an image that I had taken and being excited about it. I took photography as an undergrad, but never really thought of myself as a photographer, but thought only of using the photograph as a way to capture images for my prints, paintings, and drawings. A woman named Karen Truax was hand tinting photos ant the time, and that’s what got me started painting on photographs, although again, I was just using them as guidelines for my other work. After painting on them for about a year, in graduate school, I realized they were better than the prints and paintings I was making without the photograph, and I gradually I switched over to only painting on the photograph.

How long have you been in the Southwest and does your location impact your work?

I have been in the Southwest for most of my life, with sojourns to Mexico and South America. I think my palette is completely affected by the colors I see here(I don’t use green much for example), and of course living on the Zuni Reservation for eight years in Western New Mexico really affected my development as an artist. It was very important for me to see people living their lives in the belief of other entities inhabiting and guiding them, seeing a kind of spirituality that just doesn’t exist in our culture. My time in Mexico and Ecuador was similar.

What is your connection to animals, especially those that appear in so many of your images?

As I mentioned above, my connection to animals started at a very early age, surrounded by the animals my family kept, and then of course the wild animals that lived around me. I was lonely as a child, so animals were my friends and I knew and loved them as my very best friends. Horses and dogs are the animals that meant the most to me, but my vocabulary of important animals includes deer, birds, coyotes, snakes, and cats not so much. Horses seem to be the animal that comes up the most. And even though they are somewhat of a cliché, coyotes as well. My animals live in a different, but parallel world, and I think I’m always trying to connect the two with my images.

How did you establish your unique way of working? Did you start out as an artist or a photographer?

I started painting on the photographs I took as source material, and then they evolved in to their own powerful way for me to make images. When you paint over a photo, you never lose the photo, so I could go back in and wipe and change it until it was right, which you can’t do with prints of paintings with the same kind of freedom. So, in combination with oil paints, I discovered a way of working that suited my impulsive hasty nature. I did not start as a photographer, and rather morphed into that as I continued to develop as an artist. It, of course, took many years of experimenting and trying things out to get to that point. Then in 2004, I reversed my process and began to paint first, and then apply photos on top of the paint, switching from oil to acrylic.

What has been your biggest challenge?

My biggest challenge has been trying to negotiate and understand the business of art-the politics, how to promote myself and further my career. It’s such a flakey, fickle world that is so often based on fashion and trend, and now with the internet it’s even more of a challenge. I think so many of us artists are just not very good at this.

How did the San Diego show come about and your significant donation to the museum?

The San Diego show came about because of Deborah Klochko, the former director of MOPA (now retired) She has always been a fan of and very supportive of my work. Even though she is primarily photography based, she always loved the abuse I heaped on my photographs.

About the San Diego Museum of Art

Providing a rich and diverse cultural experience, The San Diego Museum of Art houses some of the world’s finest art. Located in the heart of Balboa Park, the Museum’s internationally renowned collection of more than 32,000 works—dating from 3000 BC to present day—includes Spanish and Italian old masters, the Edwin Binney 3rd Collection of South Asian paintings, East Asian art, art from the Americas, Modern and Contemporary art, and the Museum of Photographic Arts at The San Diego Museum of Art (MOPA@SDMA).

The Museum regularly features major exhibitions of art from around the world, as well as extensive cultural and community engagement programs for all ages. The San Diego Museum of Art hosts experiences that invite visitors to explore art through music, dance, film, food, and so much more. At The San Diego Museum of Art, exhibition text is always in English and Spanish.

The Museum of Photographic Arts at The San Diego Museum of Art (MOPA@SDMA), a distinct gallery space also located in Balboa Park, is a vibrant center for visual learning. Located in the Casa de Balboa on El Prado, MOPA@SDMA brings an outstanding collection of film, video, and still photography to the community.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

A Collaborative Photographic Exhibition by Heather and Ben Mattera: Weight of It AllMarch 7th, 2026

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Landscape ReEnvisioned Exhibition At the Monterey Museum of ArtFebruary 26th, 2026

-

Femina at Gallery 169February 20th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026