Healing Riverbanks: Sebastián Mejía’s Walks Along the Mapocho River

This week is dedicated to photographers making work in Chile across a variety of genres. Today our focus is on Sebastián Mejía, a Peruvian-born photographer and educator residing in Chile whose work explores . An interview with the artist follows.

The relationship between nature and the urban landscape has been at the center of Sebastián Mejía’s photographic oeuvre. His latest long-term project, Mapocho, depicts the transformation and resilience of the Mapocho River, inviting us to see and rethink a long-stigmatized and sullied place with renewed vision and hope. Once one of the most polluted waterways in the Chilean capital, the Mapocho has been recently declared a protected wetland.

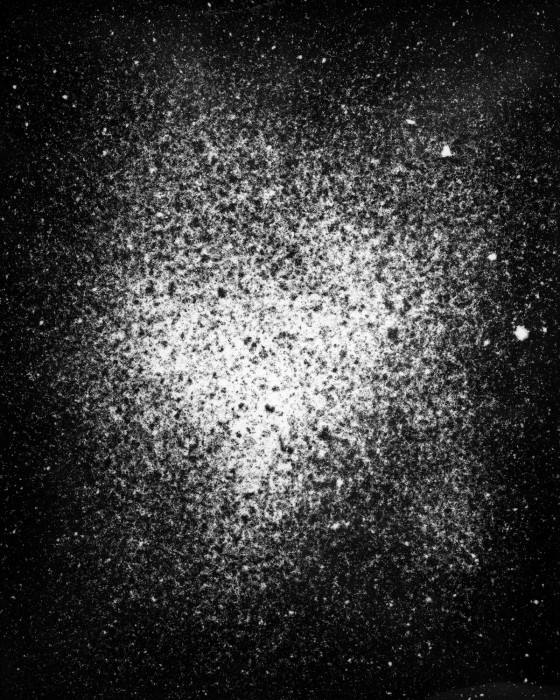

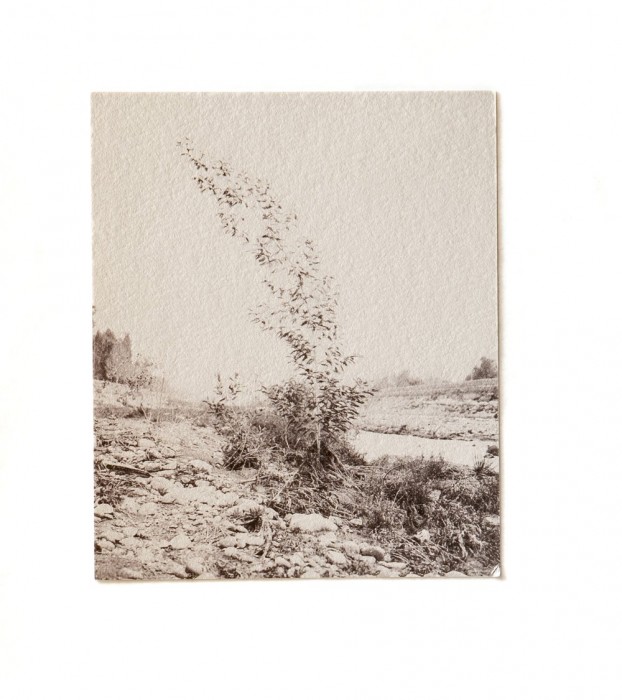

Yet, as the Peruvian-born artist notes, the river is still an often-overlooked place amidst the urban fabric. Through his lens, Mejía invites us to pause and encounter a thriving ecosystem that is slowly emerging from decades of neglect. Moving across a variety of photographic formats and styles, including photograms and pictures captures in expired film with a large format camera, the images range from the literal and vast to the surreal and intimate.

Last year, I had the pleasure of meeting Mejía and his photography students at the college where he teaches in Chile. Today, I am honored to present his newest body of work, which has recently been acknowledged as the winner in the Plant Life category in IMA next’s International Photo Competition.

Sebastián Mejía. (Lima, Peru, 1982) Bachelor Degree in Photography from the School of Visual Arts in NY. MFA from Universidad Finis Terrae in Santiago de Chile. Photographer and teacher based in Santiago de Chile. Sebastian Mejia´s photographic work focuses on primitive life that commonly goes unnoticed in the modern metropolis. His work has been showcased in numerous exhibitions in Chile and abroad including Nous les Arbres at the Fondation Cartier (2019) in Paris, Urban Impulses at the Photographers Gallery in London (2019) and Quasi Oasis at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Santiago(2013).

Follow Sebastián Mejía on Instagram: @sebastianmejiaphoto

VI: Sebastián, congratulations on being selected as IMA Next Award Grand Prix. Can you tell us about the origins of your project, Mapocho?

SM: Thank you! I have been working on Mapocho for more than 4 years now, but it was just with this award that I started sharing the work. This project began as a means of escape from the pandemic lockdowns, going on outings with my kids, looking for open space and different stimuli from indoor life. We discovered a place so rich and complex that I returned constantly carrying my camera.

VI: The Mapocho River holds a great deal of cultural significance in Santiago de Chile, having been a wasteland for decades and, more recently, a place of resilience and ecological betterment. What drew you to it in the first place?

SM: I live close to the river and cross it almost everyday. I had been curious about this place for years because it’s a kind of an “untouched” space surrounded by prime real estate. The fact that it has been left alone helped it become a unique ecosystem right under our noses. The history of it being a site of waste disposal for years left a strong mark of stigma — and rightly so — but now it’s a place thriving with life.

VI: What was the first time you went down to the riverside?

SM: The first time I went down to the river was with my children, out of curiosity. Slowly, we started walking and discovering places that were hidden from plain sight, filled with traces of habitation — both human and animal. It was like feeling in the middle of a forest but, at the same time, right next to a highway. That bizarre combination is what I try to capture with my photographs.

VI: Sometimes I get the impression that a significant part of the population still considers it a dead, contaminated stream, despite the river having undergone intensive improvements in water treatment. Do you believe the Mapocho River is also a place of ecological myth?

SM: Certain parts of the river were declared protected wetlands last year, which means that consciousness has been growing. The lock-down also made us value these spaces more than before. Yet, the notion that the river is a place of danger and waste still remains due to decades of poor management. This is unfortunately the case with many South American cities. Recent rains have caused the river to grow increasingly and overflow in certain parts, reminding people of its importance; so I wouldn’t refer to it as an ecological myth but a place that has been certainly overlooked.

VI: I think it’s also important to talk about how the river has functioned as a stage for political expression and dissent throughout Chilean history in various forms (propaganda, graffiti, demonstrations, encampments etc.). I’m not sure if this interests you, and it’s probably tangential to the core themes of your work, but I wanted to know if this had informed in any way your interest or relationship to the river.

SM: Of course. The river acts as a connective tissue with different parts of the city, and different stages in history as well. These topics interest me very much even though this project doesn’t address them directly. Due to circumstances, I focus on my most immediate surroundings because of time. My windows of opportunity to go out and shoot are very brief. Hopefully, with the years to come, I can extend this series to cover more ground.

VI: How do you interpret the significance of this river in the larger urban landscape and in the region’s collective imagination?

SM: Its so complex! I always thought this project starts as a failure in its capacity to cover the vast amount of territory the river travels. That’s why it’s focused on personal experience: There is so much that’s left out of the frame.

VI: You have led guided walks along the riverbank with university students, how has this experience expanded your connection to it? What is something that you emphasize as an educator during these moments?

SM: My walks have been mostly solitary instances, so it was a great exercise for me to open up and share this experience with a group of students. When I do this, I usually prepare an interactive class in which we walk and explore different aspects of the river, like the sounds, the smells, the mental space evoked by this place that is so close to the highway yet so disconnected from the city.

VI: What was your camera of choice for this project?

SM: All my cameras! Phone cameras and DSLRs came first as a way to make initial observations, but the “atmosphere” of the place demanded another type of language, something more in tune with the timeless quality of the river. From digital I went to a pinhole camera, and there I started finding my way. This was during the most intense lock-down. I had no access to film. The only way to shoot with this camera was using expired photographic paper I had laying around for years. The outcome was exactly what I was looking for, more evocative and less descriptive, and from there on I started using all my analog cameras with whatever photosensitive material I could get my hands on: Large format, medium format, 35mm, black and white and color. Since I focused on a particular territory, it was necessary to return and look again with different points of view.

VI: Do you have a set of rules guiding this project? For instance, are there specific time windows or parts of the river in which you shoot these images? How often do you visit?

SM: This part of the project covers the origins of the river, coming down the Andes, to the most urban part of Santiago, where the river is channeled into a concrete space. This first stage of the river still has a lot of rocks that allow plant life to establish itself and create this particular ecosystem that includes micro-forests and recently-declared protected wetlands. I try to visit on a weekly basis but not always to photograph. Sometimes it’s very useful to put the gear aside and just enjoy the walks.

VI: Do you have an anecdote you’d like to share from your many walks along the river?

SM: I’ve had a few memorable animal encounters, once with horses that have been set free in the river. They roamed the riverbed for a few months feasting on the plant life. They did not like to be approached! I’ve also seen amazing birds. It really is a kind of contemporary sanctuary that also reminds us of our history of waste — a space that acts as a primitive connection with our origins, and also as a fragile reminder of our connection to our environment.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 2January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photography YOU Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 3January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph YOU Took in 2025, Part 4January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 5January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025, Part 6January 1st, 2026