Jesse Lenz: The Seraphim : Charcoal Press

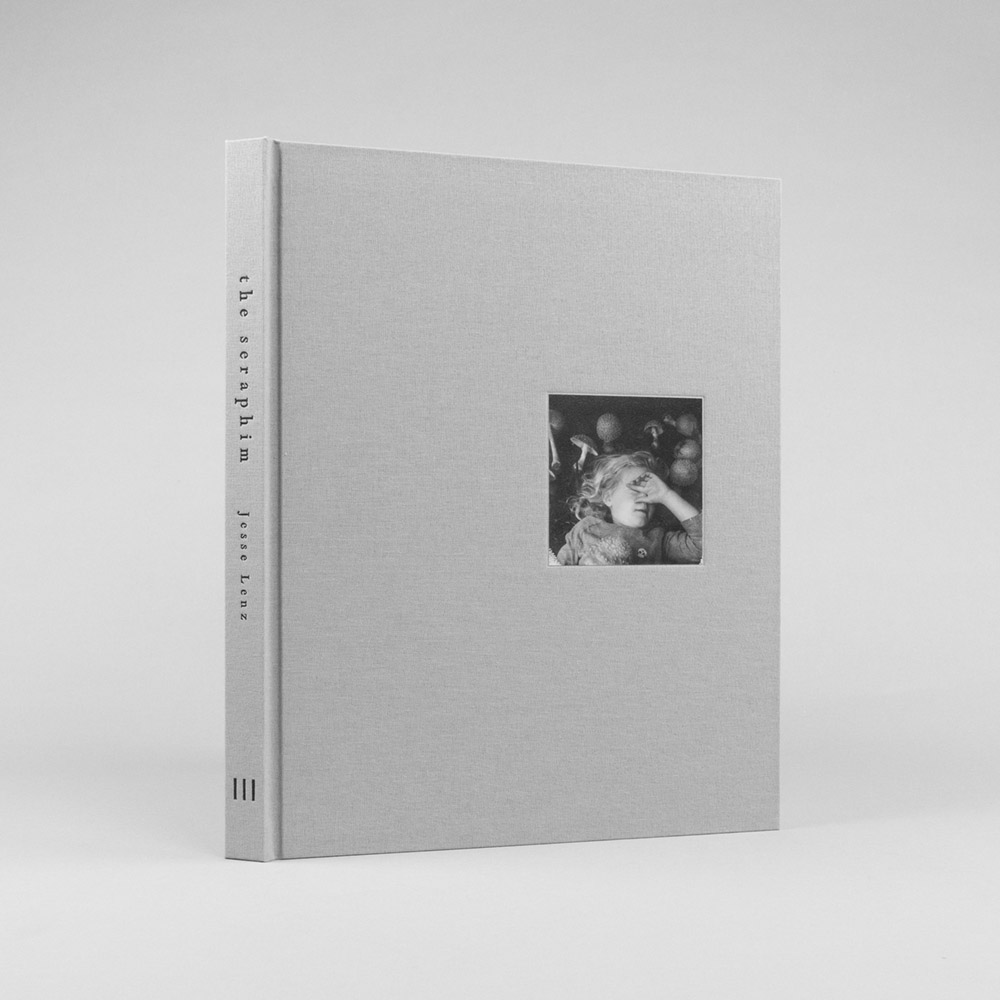

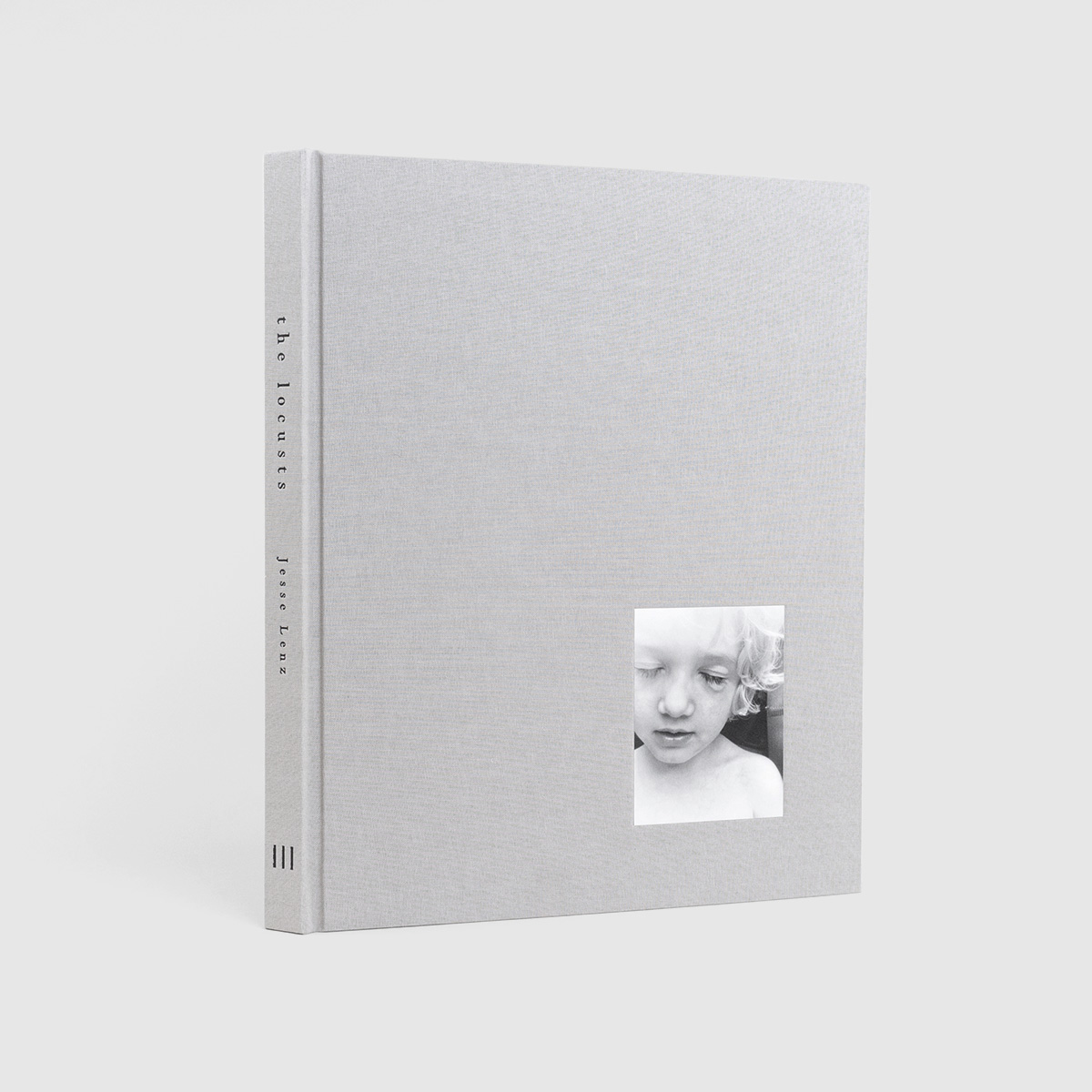

Jesse Lenz is a photographer whose work delves deep into the realms of childhood, nature, and the intricate connections between them. His work is less of a document and more akin to a fairy tale, using metaphor and mysticism to build a loose narrative of coming of age, perils and all. His two photobooks, The Locusts and The Seraphim, serve as the initial volumes of an ambitious seven-part series that explores the cycles of life and death playing out on his rural family farm. Lenz is also the founder of Charcoal Press and Charcoal Book Club as well as the Chico Review and Photobook Retreat that takes place yearly in Montana. I met Jesse at Chico and have kept an eye on his ventures since. I was interested to chat with him about the evolution of his work with his latest book The Seraphim.

The following is a transcript of a conversation between Jesse Lenz and Tracy L Chandler.

INTERVIEW:

TLC: First off, how many kids do you have?

JL: Six.

TLC: Six. And you live in rural Ohio. How did you end up there? And how does living there with 6 kids affect the work you make?

JL: It’s a long story. I grew up traveling all over the place, my father was a pastor, and then as I came of age I was traveling with metal bands and traveling to make photographs. So when my wife and I started a family we continued that nomadic lifestyle by living out of an airstream and traveling around the states. But as we grew in number, it was no longer tenable. We had 3 boys by then, bouncing off the walls. We ended up moving to the house that my wife’s family built on the farm where she grew up.

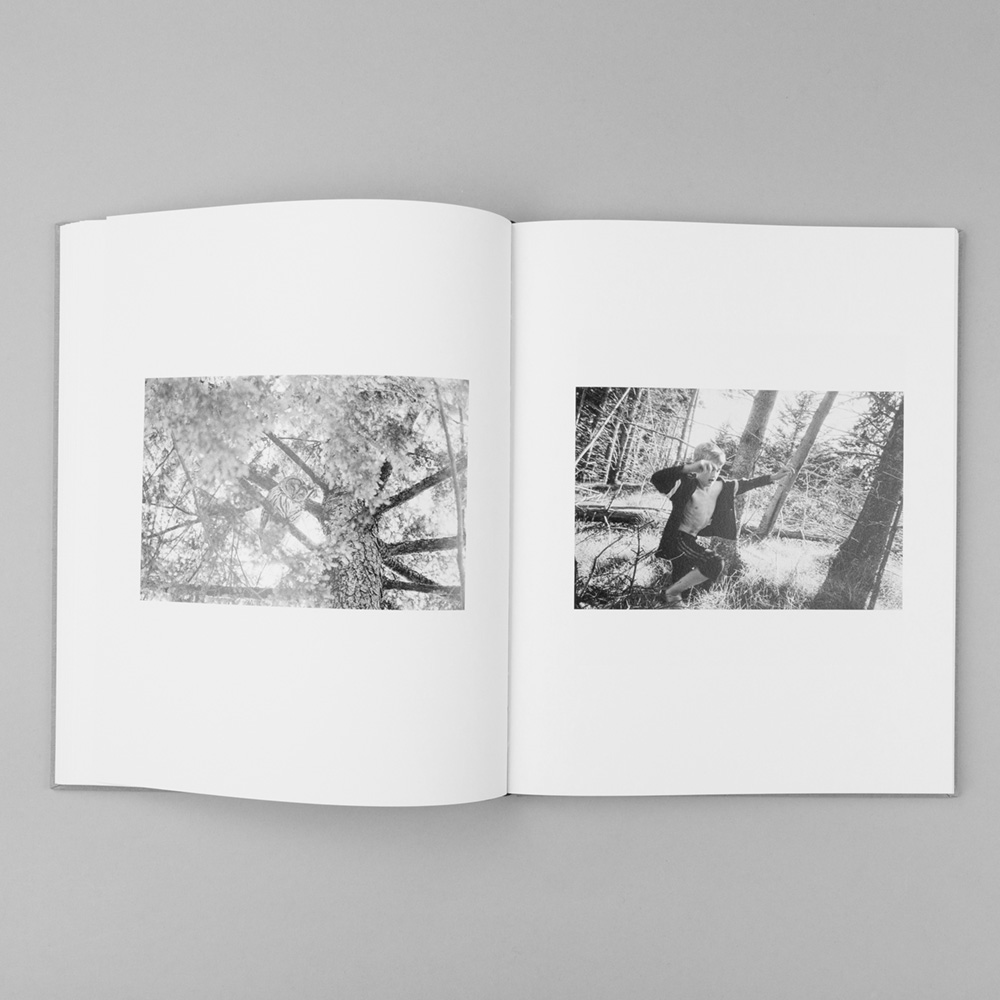

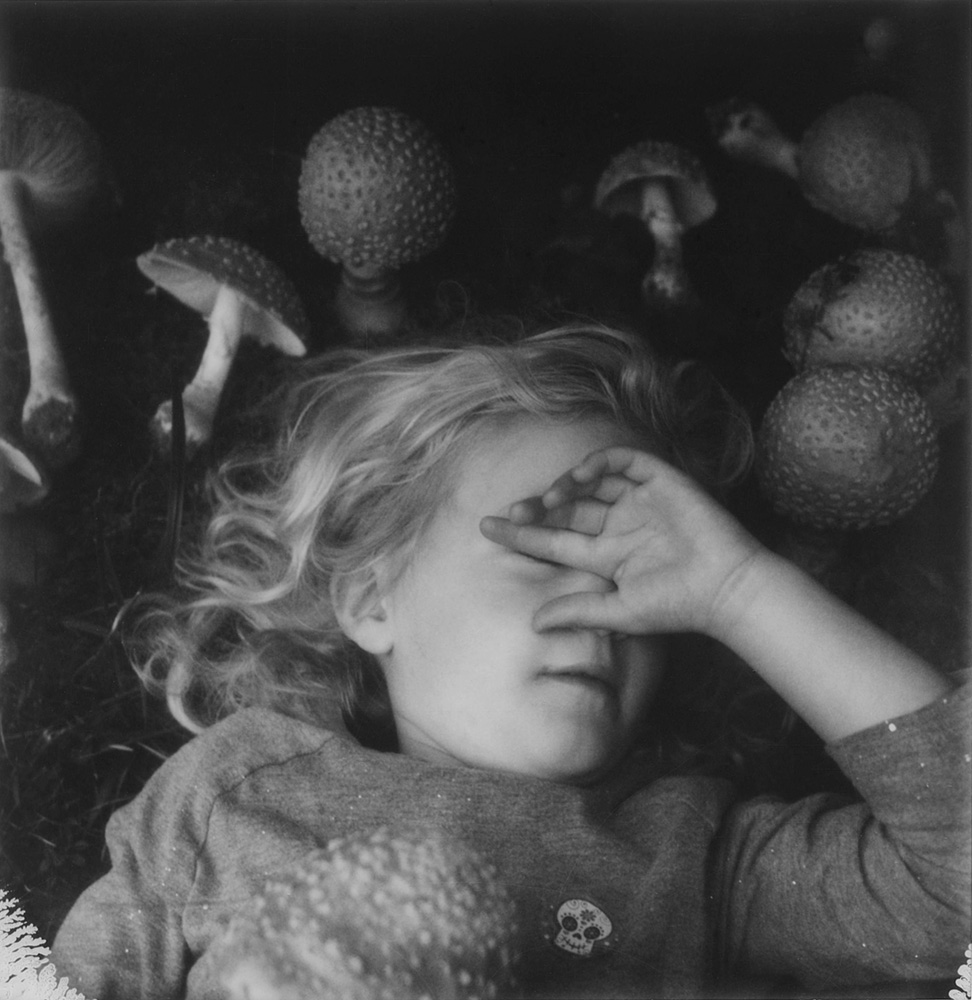

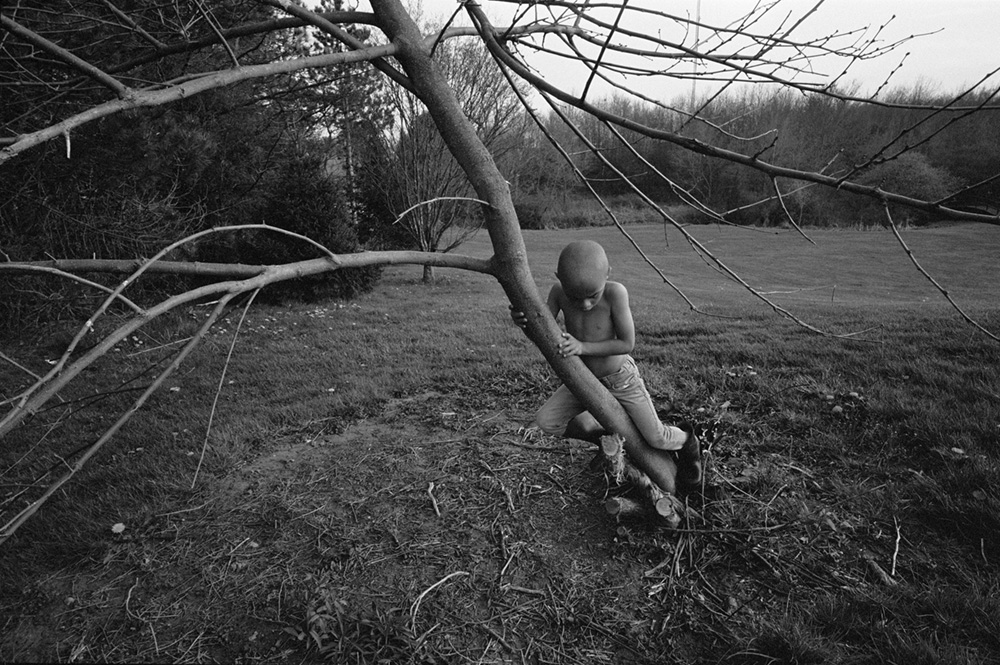

This decision marked a significant shift in my approach to photography. I transitioned from traveling to capture images to focusing on my immediate surroundings. This place, which I was initially not happy to be in, became the setting for my work. I had no choice but to embrace it and I used the camera as a literal lens or filter through which I could see the world around me as magical and mystical. I came to realize I could transform my experience in a cinematic way. I had all of the ingredients, every element that’s in a Grimm fairy tale. The children, the animals, the mushrooms, the birds. I can make my very own folk horror story.

TLC: Does that make your kids the actors? Are you directing them or are they naturally playing these characters?

JL: The kids are actors in the movie I’m making but not in a way that they are being directed or playing out specific roles I’ve dictated. They are part of my life, and I photograph everything that’s around me. It’s about finding moments where they’re not putting on a show and capturing the essence of their experiences as they naturally occur. My approach is reactive, capturing life as it unfolds. I’m never posing people… It’s just like, “Hey, get your boots on, we’re going to go for a walk because you guys need to get outside.” In essence, the process is deeply integrated into our daily lives, not separate from it.

TLC: How do they feel about that integration? There are 6 of them. I imagine they all have different experiences. Do they like being photographed? Do they have ideas for scenes in this movie?

JL: My kids don’t know anything different. But ultimately, I think kids like being seen. I think people do too. It’s one of my big disagreements with the concept of photography “taking” something from someone. Growing up traveling the world, I realized pretty early on that when you show real interest in someone or someone’s culture they like it. Those people love being seen, they love telling you about their history. For me, because I only look at things through my camera that I truly love, it’s a recognition. In some cultures or religions, to speak the name of something is to give it life and I feel like photography is the same thing. I’m using my camera to look at things that I never want to stop looking at. I’m a photographer and I photograph everything in my life, especially my family. And I think those intense times we have together are enjoyable because we’re together. The fact I’m taking pictures of them, I don’t think they really care one way or the other.

TLC: Do you anticipate that changing as they get older? I ask as I know that my own son’s openness to being involved in my art has ebbed and flowed over the years. Do you ever have to push to get the picture you want?

JL: I am looking forward to that evolution, learning to photograph teenagers in the same transcendent way as I do now. I am sure there will be times that they won’t want their photo taken. But they’re kids. They don’t want to do chores, they don’t want to eat all their vegetables, they don’t want to do many things…that’s just part of life. I photograph everything around me; if they’re around, they’ll be in photos. As kids get older they roll their eyes, get embarrassed of their parents and struggle to find freedom through rebellion. I am interested in witnessing that. Plus, we have six kids; there’s little room for ‘privacy’ in the traditional sense. Kids need to be part of something, even if they don’t always want to: sports, family vacations, etc. However, they also love seeing themselves in the way the camera renders them. Like they are in a movie. I remember my son telling me one day when I was watching a Bergman film that it looked like a movie made from pictures I make…which I pray he always thinks it was I who influenced Bergman and not the reverse!

And look, I have no interest in documenting reality. These pictures aren’t “about” them; they’re about capturing the essence of growing up, which is universal. It’s less about any accurate representation and more finding these moments where they become archetypes. My challenge, like a director, is to find the moments when they are giving a great performance, often when they don’t realize it. I have lots of great pictures of them that they love because they’re goofing off, or because it’s a funny picture. But the photos I choose for the book are usually these weird moments where something happens and it elevates beyond that.

One of things I’ve always said about making work about your family is it’s one of the hardest genres to actually do well because we don’t really care about other people’s children. I am not buying books of other people’s kids. To make work that transcends, to actually be emotionally impactful to someone else when they’re looking at your kids, that’s really hard to do. And a lot of times it means cutting the personal and going for the more universal. That’s what I am trying to do.

TLC: Where are you in this work? Why are the parents of these children not part of this universal experience?

JL: My wife is in both books. She makes small appearances but it’s almost like Charlie Brown, like you can only see the parents’ feet once in a while. I like it being from the kids’ perspective.

TLC: Can we talk about the nature themes? What special significance do owls have for you? I think I counted 11.

JL: In many cultures owls are the link between the physical and spiritual world. They are apex predators but are often completely invisible. Growing up as a pastor’s kid, I always remember every time someone saw an angel in the Bible, the first thing the entity said was “Don’t be afraid”. When I am walking through the woods looking for owls, I keep coming back to that. I’m literally looking for something that’s invisible, and something with great power. If it allows me to, it will present itself to me and allow me to gaze upon it. As I spend time in this place in this way, slowing down, I realize there is this whole unseen world that lives directly with us. It brings me back to a time in my life where I felt that magic as a kid. The world is mystical. That is the world I am building in this narrative.

TLC: It is interesting how you are linking the natural and the biblical. Can you elaborate on the significance of the titles “The Locusts” and “The Seraphim”? How does The Seraphim pick-up where The Locusts left off?

JL: The books are in sequence of time, The Seraphim was the last 3-4 years and then The Locusts was the 3-4 years before that. Within each book the sequence is laid out as one full cycle around the earth plus a little more. So if one starts in the fall it will end in the winter or spring. The Locusts mirrors the children’s development with this kind of bright-eyed becoming aware of the world for the first time. With The Seraphim you start seeing more introduction to the predator-prey aspect of life. It’s a more intense book. There’s more death, there’s more birds of prey, there’s more beauty.

TLC: And these are the first two in a projected series of 7 books? Why 7? Do you have a plan as to what will be in the next installments?

JL: I was looking at my work, and realistically with the amount I shoot, I’m ready to do a book every four years. Four years actually feels like I’m holding on too long to get it done. But I started doing the math and if I do a book every four years, when my twins graduate high school, that seventh book will be coming out. It bookends nicely and it gives me structure to work while I am here raising these kids. Also seven is a really good number in numerology.

TLC: How does that relate to the Seven Seals of the Apocalypse? You being a pastor’s kid, It must relate, no?

JL: Totally. The idea is that in Revelations when all the seals are broken, the earth has been destroyed, but it’s also been reborn again out of the destruction of the old. So if you think about it in terms of my life with six children, my world for those 30 years will be destroyed. But it will also be reborn. I will be different and my world will be different. Who knows, we may travel again.

This idea gives me a reason to just hunker down and do this work, play the hand I’m dealt. I like limitations. It sounds really funny but I think more artists would be better artists and more productive if they self-impose restrictions on what they can do. It’s why I love shooting film, it’s why I committed to a place I didn’t want to be, it’s why I love having kids. Like all these things I’ve done have enforced restrictions on my time and my thoughts and have actually made me better because of it. I’ll never get this time back. I’ll never get my kids at this age back. This is my time to do this exact thing.

The Seraphim is available from Charcoal Press and is also available as a special edition with a slipcase and silver gelatin print.

Jesse Lenz (1988, Montana) is a self-taught photographer and multidisciplinary artist. He is the author of The Locusts (Charcoal Press, 2020) and The Seraphim (Charcoal Press, 2024) and he is the founder and director of Charcoal Book Club and the Chico Review. As an illustrator he has created images for publications including TIME, The New York Times Magazine, Newsweek, Rolling Stone, and many others. From 2011-2018 he also co-found- ed and published The Collective Quarterly and The Coyote Journal. He lives on a farm in rural Ohio.

Follow Jesse Lenz on Instagram

Tracy L Chandler is a photographer based in Los Angeles, CA.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026

-

THE 2025 LENSCRATCH STAFF FAVORITE THINGSDecember 30th, 2025

-

Kevin Klipfel: Sha La La ManDecember 29th, 2025