New England Portfolio Review: Ann Hermes: Local Newsrooms

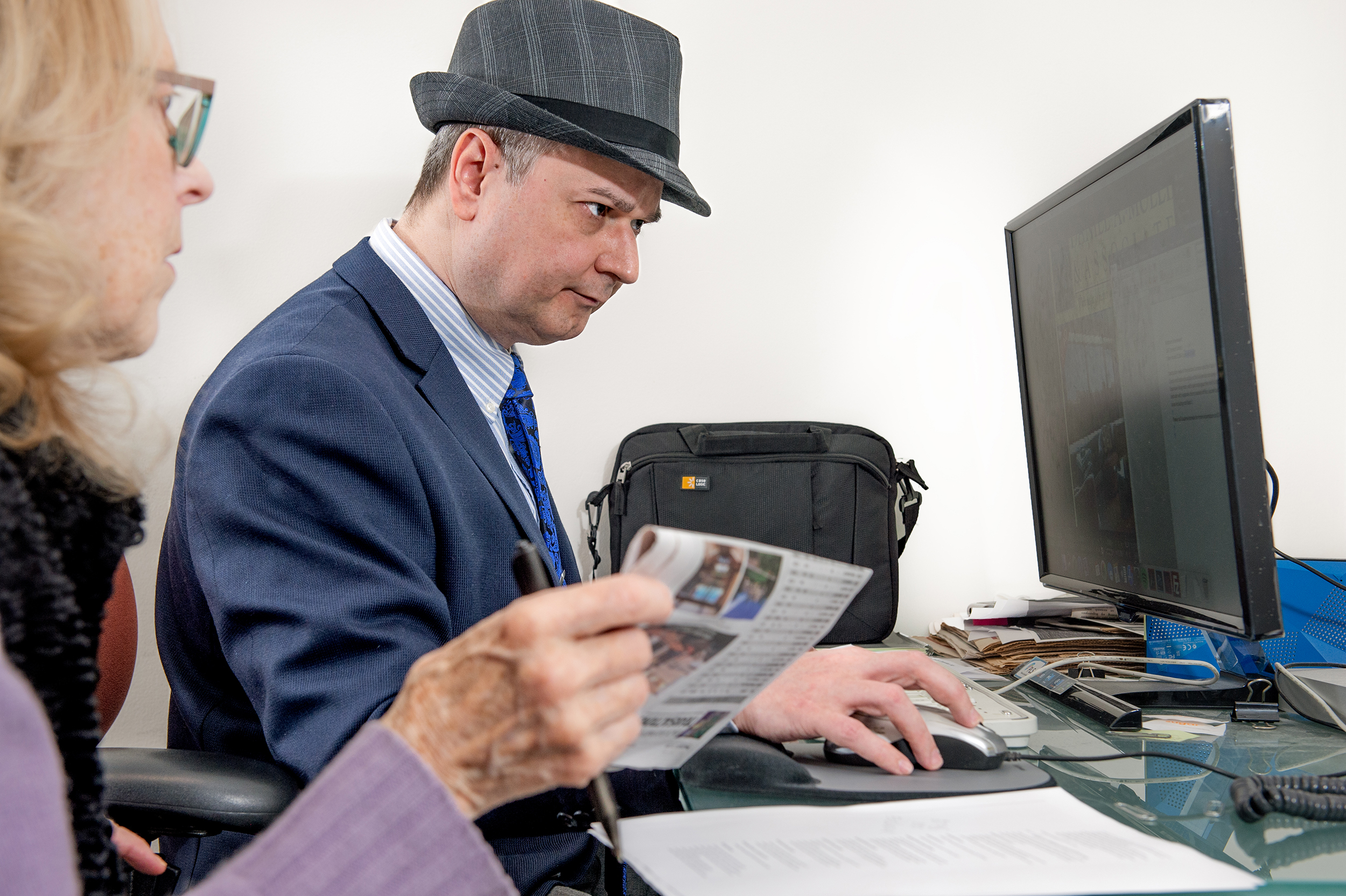

©Ann Hermes; Alameda Sun owner, Eric Kos and copy editor Veronica Hall examine proofs of the weekly newspaper before sending it to the printing press on October 30, 2019 in Alameda. The Alameda Sun closed in 2023.

Earlier this year, I was able to participate in the New England Portfolio Review hosted by The Griffin Museum of Photography and the Photographic Resource Center, I am always happy to sit down and discuss the creative work with other artists who are genuinely excited about what they are making. It is informative, rousing, and delightful. Over the next few days, I am pleased to share a few of the projects that I discovered during my review sessions. Today, we are looking at the work of Ann Hermes.

Ann Hermes is a Brooklyn and Boston-based photojournalist and visual storyteller with a flair for the nostalgic. Her personal work explores the roles that often overlooked, and sometimes outdated, institutions and people play in our history, culture and future. Hermes worked in a variety of logistically challenging situations on national and international assignments over 15 years as a staff photographer for The Christian Science Monitor and other national and regional news outlets. This work ranged from breaking visual news coverage of the Arab Spring in Egypt to in-depth stories following Syrian refugees in Eastern Europe. Her stories have also been featured in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic, The New Republic, and AARP. After years of experience in news photography, Hermes is using her documentary expertise to create a visual exploration of the current critical era in journalism and explore the potential harm that the loss of local newsrooms would bring to our democracy.

©Ann Hermes; The Conway Daily Sun newspaper morgue in Conway, New Hampshire on April 21, 2023. The free newspaper was founded in 1989. The printing press connected to the newsroom ceased printing in 2023.

Local Newsrooms

Over 2,000 local newspapers have shuttered since 2005, leaving many communities as complete news deserts. In their place is an information landscape of nationalized, and increasingly partisan, news that is ripe for bias and misinformation. Without robust local watchdogs to engage communities, government spending goes up, damaging social media rumors go largely unchecked, and city council and school board meetings take place without witness or scrutiny.

The rise of “fake news” rhetoric fueled public distrust in the media, a feeling rooted, and not without reason, in the perception of journalists as elitists out of touch with rural and suburban communities. But on the local level in news, this couldn’t be further from the truth. The journalists who keep local newspapers running are often born and raised in the towns they cover, and shop in the same grocery stores as the police officers they report on. These reporters and editors strive to be as relevant as possible in their coverage, but have seen their humble institutions decimated by an unforgiving economic model.

“It’s still scary just to look around and see how many news deserts there are and how many small communities lose their paper, but we just try to be as local as possible so we make ourselves indispensable,” said Connor Raborn, editor of The Hammond Daily Star.

I’ve been working in newsrooms for over 15 years, and I have a lot of respect for these endangered institutions. To highlight the importance of local news and the scrappy dedication of these often underpaid and overworked staff, as well as the realities of the steep challenges they face in an informational world dominated by hyperbolic cable news and a workforce that is critically lacking in racial and ethnic diversity, I’ve been documenting newsrooms across the country. From Alaska to Florida, I’ve captured the coffee-stained carpets and harried staff that make up the institutions that bring small communities the news.

With a growing catalog of images, video and interviews, I’m working to create a visual story of regional and national relevance. I plan to display some of this work in small town libraries, and similar spaces to make local newsrooms more visible in their neighborhoods. My goal is to use this work to engage communities in the search of and support for trusted local news while at the same time raising the importance of this issue to a national audience that may not have fully realized what has already been lost, and what is at stake.

©Ann Hermes; From left, owner and editor, Gen Tracy and paginator, Bob Henry, work on the latest edition of The Boston Guardian in the newsroom on April 10, 2019 in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper was founded in 2016 by David Jacobs, former publisher of The Boston Courant, which closed.

Daniel George: What first led you into local newsrooms, and what motivated you to begin this project?

Ann Hermes: The inspiration for this project was instant and visceral. I was back in my hometown visiting the local newspaper for the first time. They had just won a Pulitzer Prize, but my family was complaining that there was less and less local coverage. When I walked into the newsroom it was unexpectedly empty and there was an expanse of bare carpet with the outlines where desks had been. I knew if I showed my family that scene, they would understand what was happening to their local newspaper.

©Ann Hermes; Copies of the Marion County Record reporting on a police raid in August, 2023 are posted outside of the newsroom in Marion, Kansas on December 19, 2023.

DG: In your artist statement you write about the “scrappy dedication” of these individuals. I think that description also applies to the visual character of the places that you capture in your photographs. There is an endearing, chaotic quality to the environments. Almost exactly how I would imagine them looking. I can imagine it might feel almost overstimulating for a photographic eye. How did you approach this—parsing through all the potential subject matter and finding that which best tells the story?

AH: I’ve been a newspaper photographer for nearly 15 years and the early part of my career was spent in local newsrooms, so I understand how they work and what to highlight. I known to look for the police scanner, I know to ask where the newspaper morgue is and I know that I can usually find a bottle of whiskey in the office supply closet.

I also like to focus on older newspapers that maintain historic buildings where you can often find over a century’s worth of history on display in the chaotic collection of negatives, reporters notes, newspaper clippings and knick-knacks. It’s also poignant to see legacy instructions work to redefine their relevance and relationships to their communities.

DG: One thing that I appreciate is that your images have the visual language of journalistic photography, which makes sense because you’re a photojournalist. The voice of your lighting is very distinct and has a nice feeling of harmony. Would you speak to the style that chose to employ for this series?

AH: Most photojournalists employ a ‘run and gun’ approach out of need and necessity. Working with minimal lighting and equipment allows you to minimize your impact on the scene and capture a greater sense of intimacy. I wanted to explore a visual aesthetic outside of the photojournalism norm in part because I liked the challenge and because I had the luxury. When I visit local newsrooms, I’m not on deadline and I spend a great deal of time in these spaces watching for somewhat minimal action. I can use studio lights to add drama, illuminate every coffee-stained corner of the newsroom, and combat the ugly florescent lighting I’m usually dealing with.

DG: You mention that you envision these photographs being exhibited in spaces like libraries within these communities. Would you talk more about why you feel it is important that this work engage with both smaller and larger audiences?

AH: The loss of local newspapers impacts the communities they serve in a multitude of ways from a loss in voter turnout to an increase in government spending. The impact on our national democracy is slower to emerge, but the impacts within the community are more immediate. The most important audience I need to reach are small communities. That’s why I’m taking this work on the road to display in the communities where I photographed the local newspapers. I want residents to consider what local journalism means to them, because newspapers can only survive if their communities are engaged in their preservation.

DG: The idea of “news deserts” is an urgent theme of that this body of work addresses. As you put it, “Without robust local watchdogs to engage communities, government spending goes up, damaging social media rumors go largely unchecked, and city council and school board meetings take place without witness or scrutiny.” Do you feel this work can help inform and perhaps aid in the preservation of local newsrooms? If so, how

AH: News deserts and ghost papers are present in this body of work. Some of the institutions I’ve photographed have closed and many of them continue to cut staff beyond what a healthy newspaper can handle. I hope this work helps local reporters and editors feel seen for their underpaid and difficult work and I hope viewers consider the need for rigorous and factual community journalism for a healthy democracy.

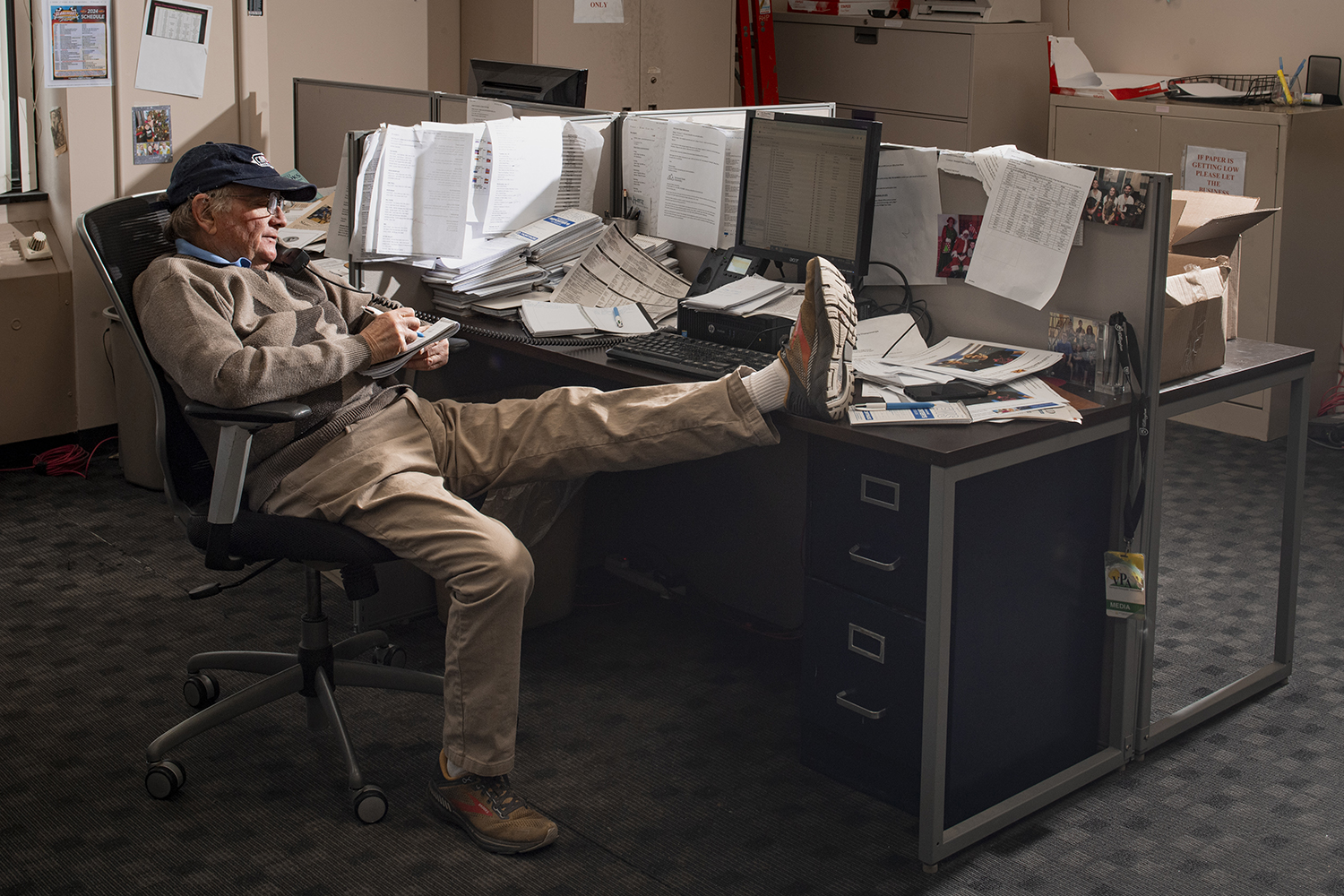

©Ann Hermes; Sports reporter, Tom Haley takes notes during an interview at his desk in The Rutland Herald newsroom on February 22, 2024 in Rutland, Vermont. The Rutland Herald, founded in 1794, is the second largest newspaper in Vermont.

©Ann Hermes; Newspaper morgue in The Marion County Record newsroom on December 19, 2023. Long-time editor and owner, Joan Meyer, passed away shortly after a local police raid on her home and the newspaper. The paper was founded in 1869.

©Ann Hermes; Cliff Tagaban, a Circulation and Distribution worker, checks the printers for the Juneau Empire at the printing plant adjacent to the newsroom on May 26, 2019 in Juneau, Alaska. The Juneau Empire has been “The Voice of Alaska’s Capital Since 1912″.

©Ann Hermes; Louie Graffeo delivers copies of The Post-Gazette for his girlfriend, publisher and editor, Pamela Donnaruma in Boston, Massachusetts, on June 8, 2023. Originally founded as La Gazzetta del Massachusetts, by Pamela Donnaruma’s Italian grandfather, the Post-Gazette is the oldest ethnic newspapers in the US.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026