Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas Breault

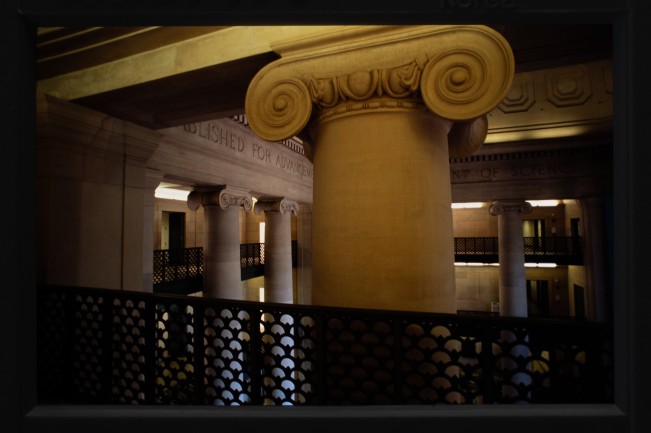

Nathan Bolton is a photographer from Boston, Massachusetts who zigzags the campuses of Harvard University and MIT as an outsider, attempting to understand how the elite mega-machine operates. These institutions function similarly to Vatican City, semi-sovereign powers embedded within larger cultural systems, wielding expansive global influence and financial resources that far exceed the physical confines of their campuses. Bolton’s analog, street-based photographs navigate the bewildering entanglement of these elite educational systems with political access and their capacity, or refusal, to exert meaningful influence on issues such as the genocide in Palestine and the legacies of the Sackler and Epstein families.

Bolton’s work is direct rather than overtly philosophical. He develops a visual language fixed on architecture, atmosphere, and happenstance to depict these institutions more intimately than the idealized narratives presented through television or marketing materials. His focus rests on the odd spaces and peripheral moments that quietly signal the imbalance between educational utopianism and global responsibility. As wealth inequality continues to widen across the region, the campuses operate as microcosms that sharpen the divide between those who are granted access and those who are cogs in the machine.

Boston and Cambridge are cold cities even outside of winter, known for the lingering odor of Puritanical values and overtly racist histories. These conditions seep into the visual fabric of the institutions Bolton photographs.

His approach is not prejudicial but democratic: observational, unmanipulated, and often ambiguous. The photographs do not always announce themselves immediately, but unfold with time and context. Bolton’s goal is to self publish a book with the photographs and research to further contextualize the histories of these institutions. Through countless hours of walking Harvard and MIT’s grounds across all four seasons, Bolton has produced hundreds of images that converge into an alternative portrait of institutional power and its domain. He photographs people and architecture with equal curiosity, allowing the imperfections of rapid, instinctive shooting to surface tensions embedded in symbols, language, and chance encounters.

This project started as most of mine seem to. First, I go to a place for the first time, or return to it after a time away, and notice I find it photographically interesting. This is both a material reaction – it looks good – and a cultural one – what are the events and thoughts that lead to the former?

This usually then goes into a mental Rolodex and sits there for a while – in this case a year. Eventually circumstances align that it seems time to start a project.

This time, I first moved across the river from Allston to Somerville (which abuts Cambridge for those from outside of Boston) – then a week after Hamas’ October 7th attack on Israel, while going for a walk with my camera, I encountered a large protest on the steps of Harvard’s library in support of a free Palestinian state.

It was then that employing Harvard and MIT to investigate contemporary United States Hegemony began to formalize. The arc of America in the 2000s with its deployment of hard and soft power across the world (concepts themselves invented at Harvard’s JFK School) had its genesis in both the foreign policy and military technology developed by these institutions and their graduates.

The photographic sequence is split with several interstitial texts that illustrate this connection – one contains two press releases, the first by Lockheed announcing Israel’s purchase of their F-35 fighter jets, the second by MIT announcing a partnership with Lockheed.

There were probably only a handful of times that someone reacted negatively or even at all to my photographing. Lots has already been said about the reduction of things into existing only for photo-ops, and it seems to be a process that America has becoming exceedingly good at – and one which has been rapidly amplified beyond over the past decade and half by social media and one of Harvard’s most famous dropouts.

Harvard, MIT and the Ivy League have become one of our main cultural exports, along with Rock n’ Roll and Neoliberalism, and folks seem to have grown accustomed to the thousands of visitors seeking the perfect piece of content. These pictures are in part attempting to parse what it means when we assign a brand to our institutions, and the ways in which their prestige are used to make the uncomfortable or destructive aspects of the technologies and policies they produce more palatable.

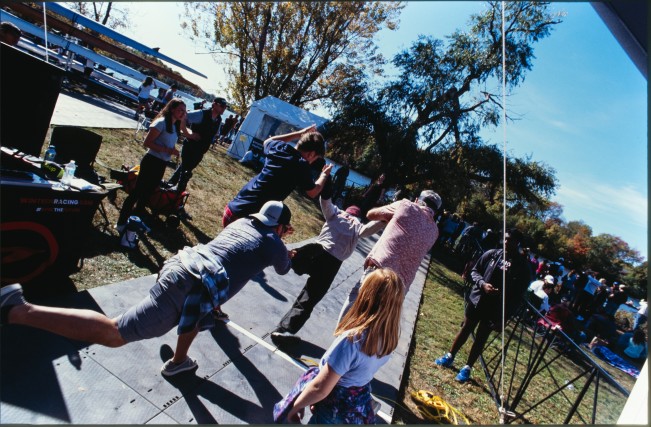

The most notable of any responses to my photographing was at the very beginning of my work when protest organizers confronted me at the steps of the Harvard Library asking who I worked for. They let me be after I assured them I had no employment other than my own interest — but would go on to physically block a credentialed reporter from photographing, an act which is shown in the project. This interaction colored the rest of my work, and reaffirmed my feelings that protest is starting to cease to be an effective tool – and as mentioned above, has become something that exists only to be perceived and photographed.

I think that I have reached two main conclusions through the course of this work. One, is that sympathy must be offered to the students and faculty of Harvard and MIT – regardless of if one thinks their beliefs and association with the institution are incorrect or hypocritical.

Enrollment or employment at either institution often means a material benefit (income or prestige) that many

would accept in a moment. And given the economic condition of the country, who can blame the protestors who camped on the schools’ campuses giving in when their degrees were threatened, or staff whose employment was at stake. Certainly not I – whose response to violence by our country and allies is just to take pictures.

In turn, there must mention of how these schools and the economy they’ve created have propelled the city and state to the upper echelons of education, healthcare and safety rankings in the country — and an examination of their positions as the Cities’ largest real estate holders who have profited from the ongoing cost of living crisis. Two things can be true.

This brings me to my second conclusion – which is that all of us as Americans are also engaged in a similar relationship to our country. In my lifetime millions of people have been killed in America’s name and so also my own – does this discount our existence as being purely in a karmic debt? I don’t think so, and there is value in recognizing the ways in which the nation state operates against its proclaimed values and the views of its people. Recognition cannot be the end of the process however if things are to improve, and I hope that if this work is able to depict American Ideology and the powerlessness I feel in its face as an individual, that it is also able to encourage the realization that change will come at the hands of the many, not alone.

I don’t think that the use of film or a digital camera makes that much of a difference in the way I take pictures. I think that the main allure of film is its archival quality. Hard drives are, on a longer timeline, far less durable than properly stored slides, negatives and prints — and remote backups reliant on terms and conditions that are fickle at best. There is also a neutral color quality that slide film has that is appealing to me.

The largest difference when working, I find, is more between big cameras and small cameras, and whether one is using a tripod.

Prior to this project – I had spent a long time with a big camera and tripod – so I decided to use a small camera handheld. After a few years of that I’ve gone back to putting the camera on sticks.

This bouncing between the two helps me stay interested, as does having several rotating projects which depend on the time of year.

This said, I do think that people are more receptive when I ask to take their portrait with a 6×7 camera than a digital one. I think that the novelty has something to do with it, as does the more drawn out attention and drama that it gives to the sitter’s experience. But, I fear that like a lot of things film is getting too expensive, and I’m not sure I can see myself using it for future projects.

Nathan Bolton was born in Boston Massachusetts and moved to Los Angeles at 18. After trying to study Economics at Occidental College, and subsequently realizing he would rather stare directly into the sun than find another derivative, he found his way to The ArtCenter College of Design, graduating in August of 2019.

Follow Nathan Bolton on Instagram: @nathanrbolton

Douglas Breault is an interdisciplinary artist who overlaps elements of photography, painting, sculpture, and video. His work has been collected, published, and exhibited nationally and internationally, including at the MFA Boston, the Addison Gallery of American Art, the Czong Institute for Contemporary Art (South Korea), Space Place Gallery (Russia), the Bristol Art Museum, and the Rochester Museum of Fine Arts. In addition to being an artist, Breault writes about art, curates exhibitions, and teaches photography at different colleges.

Follow Douglas Breault on Instagram: @dug_bro

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jake Corcoran in Conversation With Douglas BreaultAugust 10th, 2025

-

Matthew Cronin: DwellingApril 9th, 2025

-

Jordan Gale: Long Distance DrunkFebruary 13th, 2025

-

Michael O. Snyder: Placing Bets on MosquitosFebruary 12th, 2025

-

Tom Crawford: OverlookedFebruary 11th, 2025